Most requests filed under state open-records laws or the Freedom of Information Act — oftentimes referred to as “simple requests” that are relatively narrow in scope and take 20 days or less to compile — are usually provided to journalists and the public free-of-charge.

But for roughly 20% of U.S. public-records requests, according to a MuckRock analysis of our data, a fee is charged. The reasons for FOIA fees vary from place to place: Some states, like Idaho and Tennessee, have ambiguous public-records laws that allow record custodians to charge fees when they deem it necessary. Others, like Colorado, have passed laws in recent years that allow local governments to recoup fees for processing requests; In Colorado, agencies can charge up to $33.58 per hour per employee, incentivizing them to invoice requestors.

And still other states, like Kentucky, have state public record laws that, while allowing for some fees to be charged, requires that they be “reasonable” and related to the time needed to search for documents. Generally, Kentucky’s open-records law has a 10-cent-per-page cost associated for most records and that hasn’t changed since the 1980s; the median cost for charged records there is about $7, the second lowest in the U.S.

MuckRock surveyed nonprofit Freedom of Information and press clubs in all 50 states and three U.S. territories to gauge the relative strength and limitations of their open-records laws and associated fees. Some groups pointed to egregious examples where governments charged exorbitant fees for records, like one state agency in Georgia that estimated that one of its datasets would cost a newsroom $17 million. At least 25 states and territories allowed for some type of fee waiver or exemption but just 10 of those specifically referenced media requestors in those decisions.

Median FOIA fees by state

Requests filed through MuckRock collect various data points, including the median costs of records state-by-state. The data is based only on requests filed through MuckRock and not on outside metrics provided by state or local agencies.

The states where the median cost for records is less than $50 are in green, median costs between $51 to $100 are in blue, and median costs more than $100 are in orange.

USA

AK

ME

VT

NH

WA

ID

MT

ND

MN

MI

NY

MA

RI

OR

UT

WY

SD

IA

WI

IN

OH

PA

NJ

CT

CA

NV

CO

NE

MO

IL

KY

WV

VA

MD

DE

AZ

NM

KS

AR

TN

NC

SC

DC

OK

LA

MS

AL

GA

HI

TX

FL

The MuckRock survey and data from more than 27,000 requests filed through our platform since 2018 point to an uneven landscape across the country for FOIA fees. Five states had the highest median costs for records: Idaho, Tennessee, Alaska, Nebraska and South Dakota, ranging from $430 to $262, respectively. Nebraska doesn’t waive fees for news media. South Dakota and Alaska do waive fees for media but often charge other types of requestors. The public records laws in Tennessee and Idaho are ambiguous; state law allows a records custodian to waive fees in Tennessee, while in Idaho the state law prohibits fees for those who cannot pay.

When drafting public records requests, experts said including some language addressing potential costs is key. This can include wording that requests a fee waiver for news media and noting that the documents will be used in published work; asking for a cost estimate prior to fulfillment; and narrowly-tailored language specific to the documents you’re requesting.

For MuckRock requests, that wording, depending on the state, usually says something like: the "documents will be made available to the general public" or “this request is not being made for commercial purposes."

Mike Hiestand, the legal counsel at the Student Press Law Center, said he also routinely tells people requesting public records to take the time to call the records custodian and set up a meeting to discuss the most effective ways to reduce costs and processing times. This gives requestors the opportunity to hear and understand what will make it easier for custodians to deliver responsive records in a timely way.

"Treat them as humans and just try and figure out what is the most effective way for you to request the records so that it doesn't cost that much," Hiestand said. “Having that kind of one-on-one human contact can take care of a lot of the problems.”

Fee waivers for media and ‘public interest’ helps combat high fees

Over the past six years, from 2018 through the fall of 2023, there were more than 27,000 public-records requests filed through MuckRock and more than 84% of those requests didn’t require a fee.

But for the other 16% of requests — roughly 4,300 in total — a fee was charged. This group includes requests that were completed and paid and those with pending charges but does not include requests that were withdrawn or canceled altogether.

Each year, the number of requests with fees filed through MuckRock has fluctuated between 13% and 20%, according to our data. To reduce the costs for records, some states have fee waivers built into their public records laws specifically for media. Others have broad exemptions that allow for requests made in the public interest to be released for free or at minimal cost.

Not all exemptions work the way they were intended, experts say, with various loopholes that can be interpreted differently depending on the agency.

Chadd Cripe, who oversees the Idaho Statesman, the more than 150-year-old paper of record based in Boise, said that costs for documents have impacted its journalism, often forcing reporters to skip using public records in their stories.

"We're not sitting on a giant pot of money to spend on public records requests," Cripe said. “So, when we get a giant bill, we either figure out if there's a way that we can lower the cost by cutting back on what we're asking for or, what happens in most cases, is just not getting the records.”

The Statesman, which has been owned by the media company McClatchy since 2006, doesn’t have a specific public records budget that reporters can use when presented with fees, Cripe said. Instead, the publication will decide if the story can work without the documents. Depending on the importance will from time to time pay the fees.

In one case, Cripe said the paper was asked to pay more than $4,500 for a series of four police-related requests. All four requests were withdrawn by the newspaper.

The Statesman’s experience with high costs for public records isn’t unheard of or necessarily unique to Idaho. In fact, various state and local agencies have doled out receipts for hundreds and even thousands of dollars in response to public records requests by journalists.

One approach that has limited success in Idaho is citing an exemption in state law that waives fees for requesters who simply can’t afford the costs. Idaho’s public records law includes a section saying that fees will not be charged if the requester "has insufficient financial resources to pay such fees." Despite this language, some agencies have pushed against the waiver, claiming that newspapers do have the resources to pay for records.

"The answer we get anytime we bring that up is ‘You're a for-profit company, so, no,’ even though we can't pay," Cripe said. “That's one that theoretically should be able to do some good, but it's not.”

In other states, like Kentucky, there are no specific fee waivers for media but public-records laws are written in ways that journalists have benefitted from.

Amye Bensenhaver, a retired Kentucky assistant attorney general and co-founder of the Kentucky Open Government Coalition, said that the state’s public record law doesn’t allow the cost of search time for noncommercial requests to be charged. She said that the law only allows for a reasonable fee for copying records, which was set at 10 cents in the 1980s and has not changed since.

"[Agencies] can also cover postage if they mail them, but it’s one of our best kept secrets," Bensenhaver said. “And, in fact, as an agency transmits records electronically, there's no charge, there can be no charge.”

MuckRock data show that the median cost for documents submitted through its records portal in Kentucky came out to $7.10, the second lowest in the country.

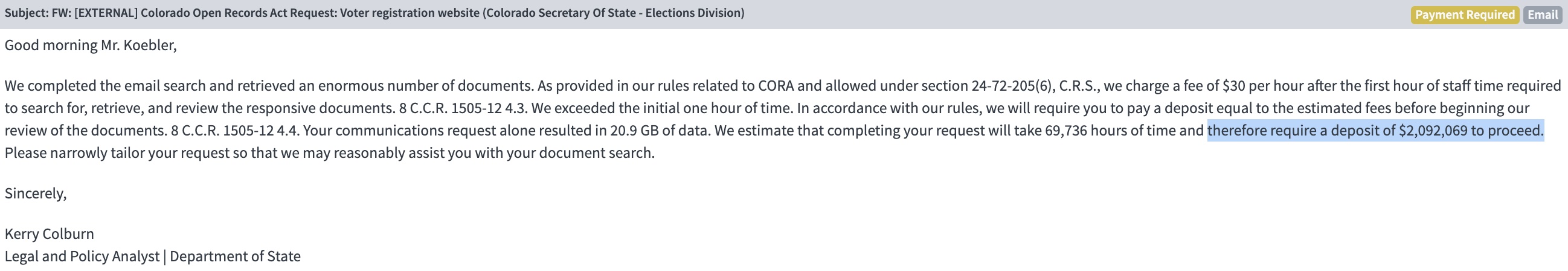

The $2.1 million request for election contracts and documents

In 2020, Jason Koebler, as a staffer at 404 Media, filed a request with the Colorado Secretary of State’s Election Division seeking information about its election process. His request asked for government contracts, plans, contracting "request for proposals" and presentations — all fairly standard public records requested by journalists.

Koebler’s request referenced several news reports for context and used language that identifies Koebler as a member of the media, which according to state law is a valid reason for custodians to waive fees. But that isn’t what happened.

In response to his request, a state legal and policy analyst estimated that it would take 69,736 hours for the Colorado agency to complete Koebler’s request.

The cost:

In an interview, Koebler called the $2.1 million fee estimate "absurd" but says the sheer size of the cost didn’t rankle him. Rather, in his view, it’s the routine, smaller fees that agencies charge that have bigger negative impacts on newsrooms and their budgets.

As part of the project, Koebler filed similar requests with nearly every U.S. state and territory prior to the 2020 election to see how their different voter registration systems stacked up to each other. For Colorado, the request was abandoned.

"I'm happy to pay fees if they're reasonable, but if they are not there's only so many hours in the day to fight things like this," Koebler said. “It's very expensive to fight fees like this.”

He added that he had never before or since received a fee as high, but he has received some in the thousands. Those figures he said are the ones that concern him more than $2 million-plus charges.

"You see something like $2 million and you have to laugh, but you see $500 or $600 over and over again and it's like you have to really think, can I afford to pay this? Are people going to care enough about these documents to actually buy them," Koebler said. “It becomes a big gamble, it can become a very real stressor on your editorial budgets.”

One technique Koebler employs when navigating fees is to embark on 50-state FOIA "sweeps," cloning one original request — essentially copying the same wording for requests like the Colorado election documents — and then tweaking and tailoring the language for other states. Some states will work, others won't, but he always ends up with worthwhile and newsworthy records.

Some states will work, others won't, but he always ends up with worthwhile and newsworthy records. For example, in South Dakota, state law exempts communication between state and public officials from public record, and even exempts documents where opinions are expressed. Across the border in Minnesota, similar records are required to be released between state and public officials from public record, and even unless otherwise classified.

"I find that very disheartening because often, other agencies will have no problem fulfilling my request," Koebler said. “And then I'm getting told [by other agencies] that my requests are burdensome.”

Strategies for reducing costs: Filing across multiple agencies and a ‘human touch’

While the Freedom of Information Act establishes blanket requirements for federal agencies, no such law exists at the state level. Instead, states are left to create and regulate their own public record laws, including costs. In one state, a requestor may be able to access internal emails between government officials at little to no cost. Meanwhile, similar records in another state might run the bill up into the hundreds or even thousands depending on the number of responsive documents.

In Texas, state law dictates that custodians can’t include the cost of labor, materials and overhead for records that are under 50 pages. But in 2017, MuckRock requested documents from the Texas Department of Criminal Justice regarding investigations of sexual assaults in state correctional facilities. The agency responded with a $1.1 million fee after the state attorney general informed custodians that basic information is releasable but names of individuals would need to be redacted.

The state quoted MuckRock more than $900,000 in labor charges and more than $180,00 in overhead, contrary to state law. The Texas Department of of Criminal Justice suggested filing the same request with the Prison Rape Elimination Act offices, which asked for $551.39 for all of their audits since 2016.

Other requests that are more complicated are likely to drive up costs because of the sheer volume of responsive records, in some cases creating fees in the millions.

According to the Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition, a 2014 change to its public records law requires the state to adjust its record fees every five years to match the Consumer Price Index for the Denver-Aurora-Lakewood areas. As a result, the coalition calculated the most recent increase would cause record processing fees to jump from $33.58 to roughly $41 an hour.

“There’s no limitation on the number of hours that a government entity can charge, so we’ve had situations where Colorado Open Records Act requests can get really expensive that actually become an obstacle to obtaining public records in Colorado,” said the coalition’s executive director, Jeff Roberts. “This has been such an issue that at one point, we asked a University of Denver law student to do a report on this for us.”

That 2020 report found that although the Colorado Open Records Act was meant to limit agencies from charging requestors exorbitant fees, many state and local bodies charge the maximum allowable rate as a “research and retrieval fee.” A survey of more than 100 Colorado school districts found that 85% of them would charge the highest amount possible.

MuckRock data shows that the median cost for documents filed through Colorado agencies was $99. However, there have been more than 30 requests in Colorado that returned fees of more than $1,000. Of those, five were more than $10,000. In Idaho, MuckRock data shows nine requests over $1,000 and one for more than $450,000.

Groups like the Student Press Law Center and MuckRock have templates and tools that help craft records requests in ways that work to drive costs down. “Simple requests,” or requests that have narrowly-tailored language, generally require less time to search for and retrieve responsive records. In most cases, specific wording helps custodians cut back on time and labor which ultimately cuts costs.

But simple requests don’t always equal low fees, and requests that may appear simple can require hours of agency search time, which leads to higher costs. Still, there are other, “soft-skill” strategies, journalists say.

Cam Rodriguez, a data reporter for the Illinois Answers Project, which describes itself as the state’s “nonpartisan investigations and solutions journalism news organization, oftentimes requests the same records from multiple agencies.

“If it seems like I’m getting trouble from, say, the Illinois Department of Public Health but, if I could get the same documents or similar documents from the Chicago Department of Public Health, I’ll try and do that,” she said.

She also regularly sets up scheduled emails when she feels that she is not getting a timely response from records custodians. And Rodriguez emphasizes the importance of remembering that the people who handle records are human and benefit from a human touch.

“Oftentimes they’re overworked just like us, and they may or may not want to look through piles of records, just like us,” Rodriguez said. “Being able to kind of help them do their job to the extent of my ability is something I always offer.

“I think it really goes a long way just to not be a dick.”