The Federal Bureau of Investigation file on Oleg Lyalin offers new insight into what’s been called “the single biggest action taken against Moscow by any western government” - the 1971 expulsion of dozens of Soviet personnel. According to the narrative established at the time, and repeated even in recent publications, Lyalin’s defection “led to the discovery and deportation of 105 Soviet officials who were accused of spying in Britain” and was prompted by a drunk driving arrest. As his FBI file shows, however, the real story is more complicated than that and has long been one of MI-5’s closely held secrets.

It’s impossible to separate the expulsion of 105 Soviet officials from the story of Lyalin. Despite Lyalin playing a significant role in the affair, equating the two chain of events, as is done in Lyalin’s obituary, recent Reddit front page posts and many other outlets, misses several key facts which are highlighted in the FBI file. The confusion, it seems, may have been deliberately cultivated; which would hardly be surprising considering the sensitive nature of this intersection between diplomacy, statesmanship, and counterintelligence. The affair is still little discussed except in sensational terms of drunk driving ending a spy ring. Even MI-5’s historical website devotes only four vague sentences to what it calls the “major turning point in Cold War counter-espionage operations in Britain.”

As The Guardian reported at the time, citing a statement from Britain’s Foreign Office, “the expulsion order - affecting nearly 20 per cent [sic] of the 550 Soviet diplomats in Britain - is unprecedented in size and scope. It follows months of intensive investigation by the intelligence services, and the defection of a top KGB officer from the Soviet Embassy in London. The KGB man, who had the rank of major, proved the catalyst for the “clearing” operation against Soviet espionage.” While The Guardian does credit Lyalin’s defection as playing a role in the expulsion, it also makes it clear that the investigation had been at least several months long and intensive.

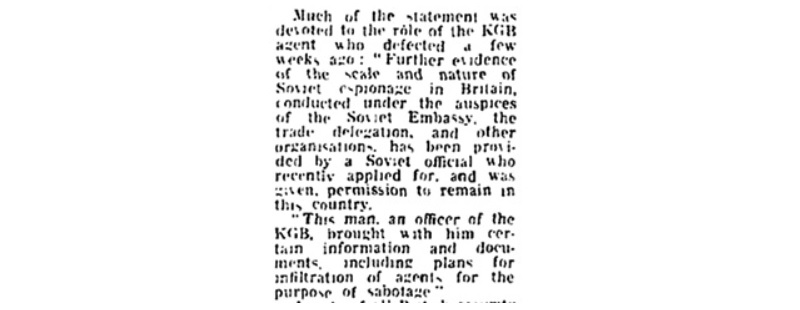

The Guardian went on to quote the Foreign Office’s statement, further cementing the perceived direct causal connection between Lyalin and the expulsion order. The Guardian can hardly be blamed for this, considering that “much of the [Foreign Office’s] statement was devoted to the role of the KGB who defected a few weeks ago.”

Known to relatively few at the time was the fact that the expulsion had been in the works for years, contrary to the reporting of BCC and others that his “arrest led to his defection to Britain and the expulsion of 105 alleged Soviet agents from the country.” It didn’t take long, however, for rumors to begin flying that there was more to what happened than what met the eye. According to the arresting officer, “there were all sorts of rumours flying that I was put in place to stop him.” He denied that this was so, saying that he didn’t know who Lyalin was before the public did. He did, however, think that the arrest “pre-empted the government - forced their hand to act quicker than they would have.” This was, according to the available records, precisely what happened.

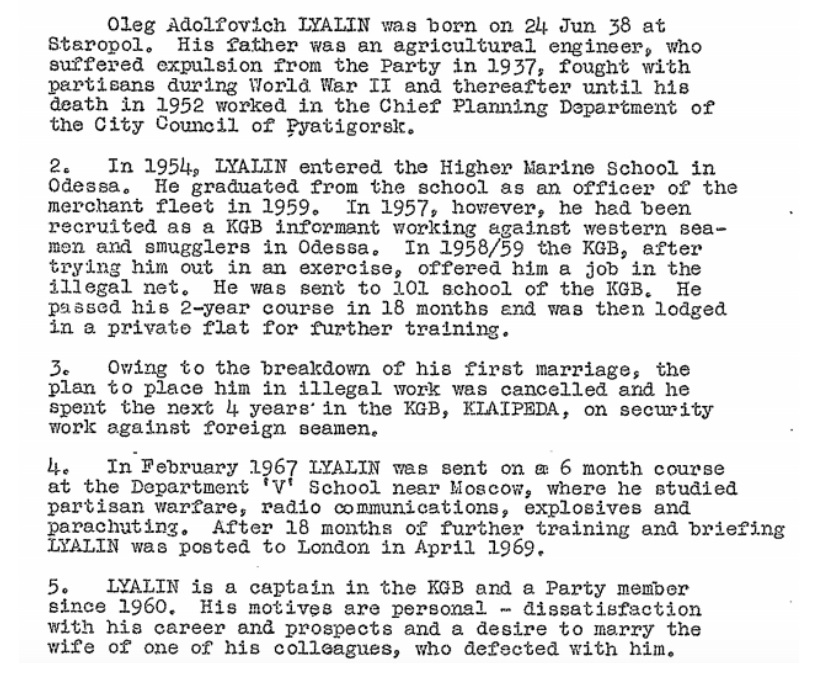

According to the FBI file on Lyalin, his initial reasons for defecting were personal, boiling down to dissatisfaction with work and a desire to be with the wife of another KGB officer. This, however, only seems to explain his initial approach to MI-5, when he essentially became a defector in place.

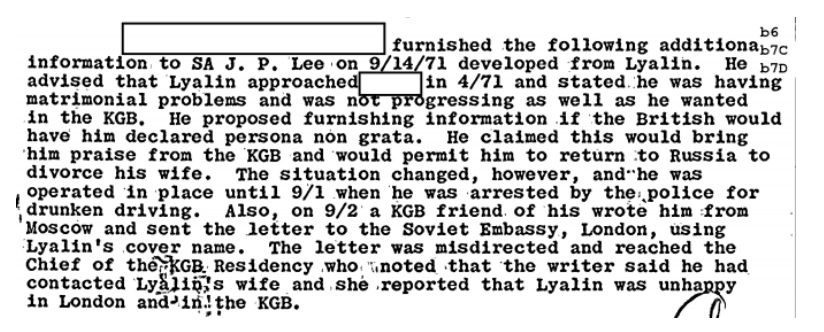

Elsewhere, the FBI file offers a bit more detail on Lyalin’s defection in Britain. According to what the FBI was told, Lyalin had first approached the British in the third week April of 1971 complaining about his marital problems and his future in the KGB. Seemingly unhappy in London, Lyalin wanted the British to declare him persona non grata. Lyalin said this would have brought “praise from the KGB” while sending him back to Russia where he would be able to divorce his wife. In exchange, he would have given the British information. Instead, the British began operating him as an agent in place - an operation that only seems to have ended when Lyalin was arrested for drunk driving on either August 30th or September 1st. (Several contemporary outlets list the arrest as having taken place on August 30th, with Lyalin being bailed out on the 1st, with other reports listing the arrest as taking place on September 1st.) This, combined with the KGB apparently finding a letter stating that Lyalin’s wife had said he was unhappy both in London and with the KGB, prompted Lyalin’s recall to Russia - and in turn, to his defection.

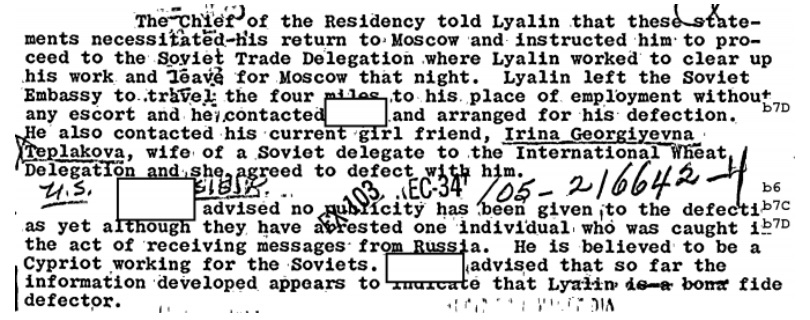

When Lyalin was told that he was being recalled, and ordered to collect his things from work, he wasn’t provided with an escort or guard. Lyalin seized the opportunity and gathered his papers from his home and his office and contacted his handler(s) at MI-5, arranging for his final defection along with that of his girlfriend Irina Teplakova.

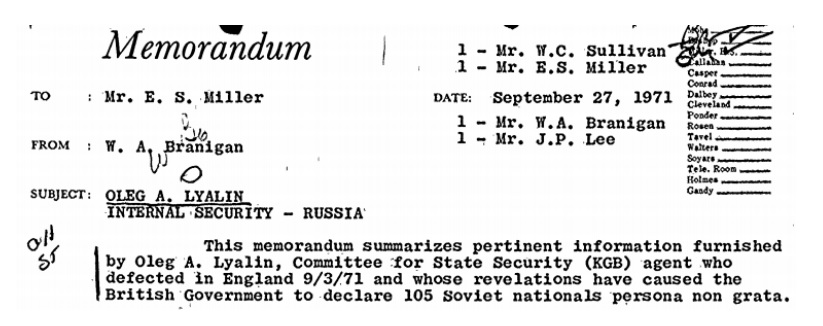

The Bureau’s counterespionage chief, William Branigan, was under the impression that Lyalin’s defection was the sole cause behind the 105 Soviet nationals being declared persona non grata.

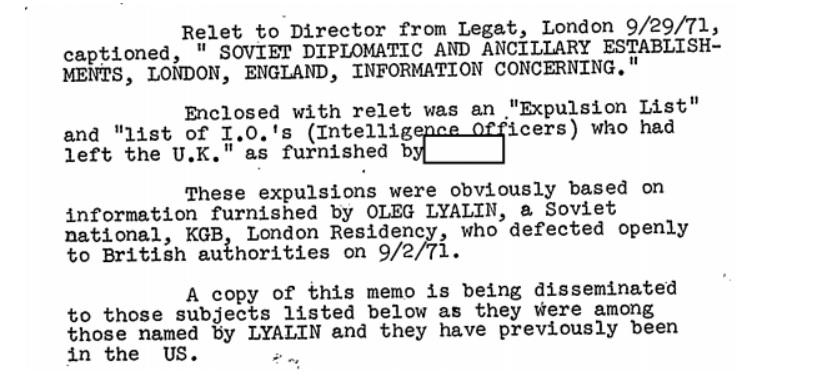

Even a month later, FBI agents working the case believed that the expulsions “were obviously based on information furnished by” Lyalin.

Even the Central Intelligence Agency was under the same impression, with a November 1971 background report crediting Lyalin’s defection and information with the expulsion of the Soviets.

Another background report from the following month repeats the claim.

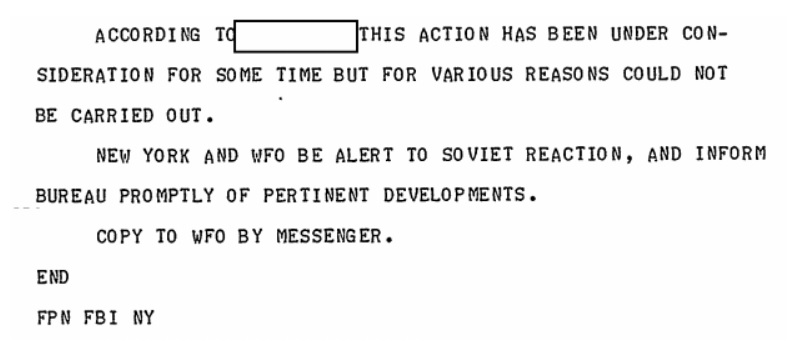

At several points, however, the FBI file notes that the plan had been underway for quite some time. The FBI Director was aware of this on the same day the expulsion took place. In one memo from the Director to the FBI’s New York Office, it’s noted that it had “been under consideration for some time but for various reasons could not be carried out.”

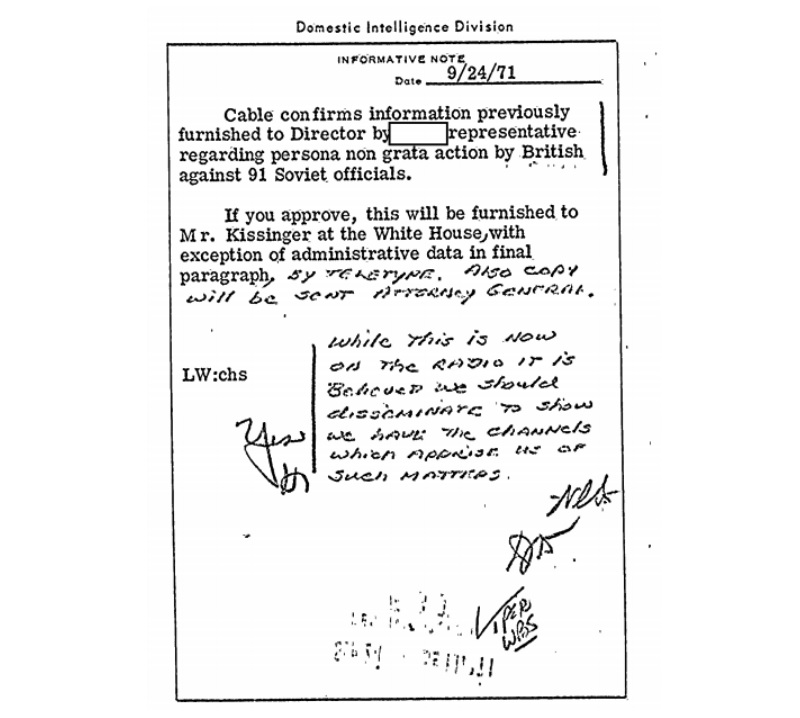

A similar message was sent to the White House Situation Room, earmarked for the Attorney General and Henry Kissinger. This may have only been carried out with the approval of the Bureau’s leadership, judging by an “Informative Note” from their Domestic Intelligence Division.

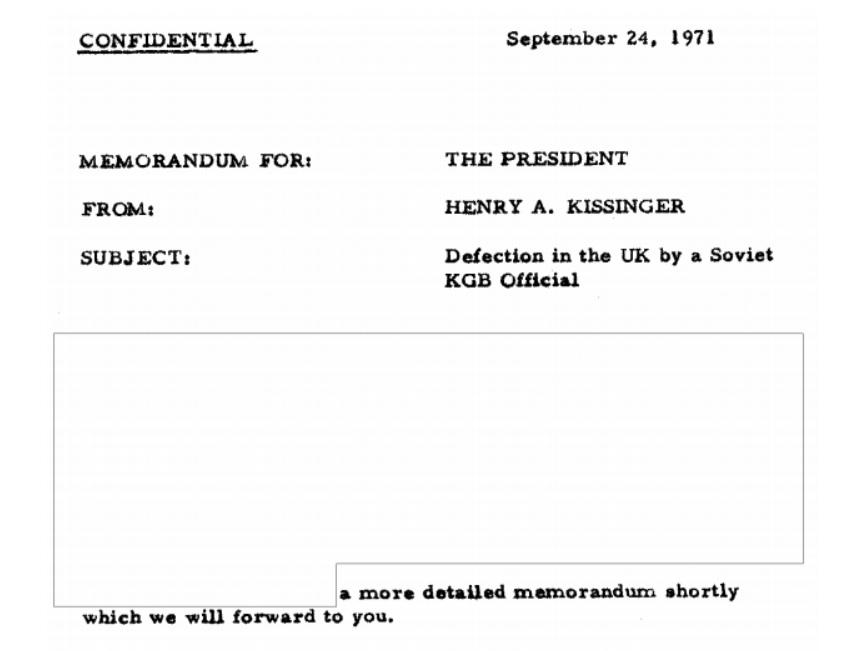

In response, Kissinger dutifully informed the President in a memo that highlights the extreme secrecy that still surrounds the case by being almost entirely redacted by the CIA. Before promising to send more detailed information in a follow-up memo, the redacted text reads: “The British Ambassador has just delivered a letter to me advising of the UK government’s action. They will expel 90 Soviet personnel, mostly from various technical missions (over 550 Soviet personnel are in the UK). The Ambassador asked that I convey to you the Prime Minister’s sincere regret. He was unable to advise you in advance as planned. A press leak broke the story and required the government to move immediately this morning.”

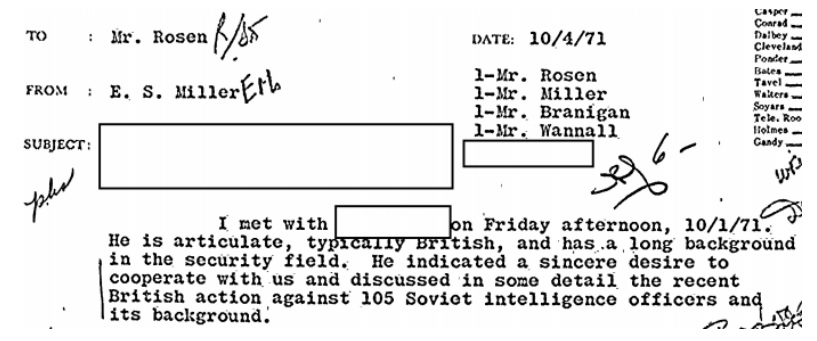

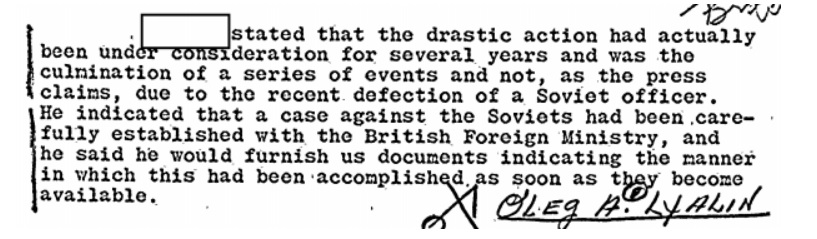

Elsewhere, the files explicitly make it clear that the expulsion wasn’t simply the result of a lucky break, but of months - if not years - of work. One meeting with E.S. Miller, who would become known for running FBI’s Domestic Intelligence Division, and an unidentified “typically British” gentleman with a “background in the security field,” provides several crucial details that contradict the popular narrative.

According to Miller’s contact, the expulsion had been “under consideration for several years.” Rather than being due to the defection of Lyalin, it was “the culmination of a series of events.” The British Foreign Ministry had “carefully established” a case against the Soviets.

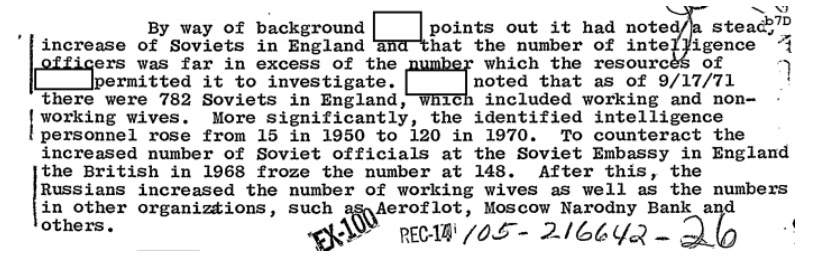

According to another memo written several weeks later, the plan had been put into place in response to the increasing number of Soviet individuals in Britain and the fact that the number of Soviet intelligence officers had exceeded what the British had the resources to investigate.

As a result, in early 1971 the British “drew up plans to deal with the situation and the Prime Minister approved this plan in early” August, following a joint memo to the Prime Minister from Sir Alec Douglas Home and Reginald Maudling on July 30th. The plan had a twofold purpose, seeking to both reduce the number of Soviet personnel in England and to disrupt the KGB in the hope of producing new leads.

The dates are both interesting as they can both be seen to correspond to significant dates in Lyalin’s work with the British. Lyalin first made contact with MI-5 in early 1971 - April - and according to several newspaper reports, had decided to defect in August or early August - when the plan was approved by the Prime Minister.

The reports of a decision to defect in early August may have been in error, however. The same British source who told Miller that the expulsion plan had been years in the making also informed him that Lyalin’s defection had been precipitated by the drunk driving incident and the misdirected note. Lyalin had originally planned to return to the Soviet Union, likely included as one of the officials who would be declared persona non grata, where he would have continued to work for the British. This was plan, carefully constructed, was apparently derailed by his drunk driving arrest and the note, the two of which may well have ended his career.

The memo summarizing Miller’s meeting with his unidentified British contact ends by declaring that the Bureau would be provided with more information based on Lyalin’s debriefings. The memo also notes Miller’s interest in reviewing the “selling job” that “was necessary” to convince British politicians to approve the action.

Although not spelled out explicitly in the released file, the “selling job” very likely involved the intelligence provided by Lyalin, albeit before his public defection. This included a plan Lyalin had worked out for the KGB, which included landings and parachuting into England, the U.S. and Canada for sabotage purposes.

Lyalin had also been engaged in selecting landing sites in the UK for Soviet forces, and had developed a network of agents within the UK. This network would have, when activated, given Lyalin a “self-contained operational base” and help prepare for and support the arrival of Soviet sabotage teams and their activities.

Based on Lyalin’s information, government officials concluded that the Soviets were preparing to begin sabotage operations in the UK to create a “prolonged crisis, leading up to the outbreak of war.” The sabotage operations would have sought “the demoralisation of the civilian population and the complete disruption of the political and economic life of the country.”

Lyalin also exposed Russia’s plans to contaminate the water in Holy Loch, Scotland, and blame the presence of the U.S. Navy. Holy Loch was used as the base for Submarine Squadron 14, a significant piece of America’s deterrent forces against the Soviet Union. Poisoning the water with an eye to implicate U.S. Naval forces would have been tantamount to a false flag attack, even if it were staged to look like an accident. The Soviet Union’s interest in the Holy Loch would be publicly reinforced a few years later when one of their submarines collided with the USS James Madison.

The information provided by Lyalin deemed credible, with officials finding “no reason to doubt” him.

Outside of Lyalin’s information, however, the Foreign Office and MI-5 had spent considerable time building the plan and attempting to convince politicians that it was both necessary and practical. Lyalin may have been part of the “selling job” to finally convince the politicians that the expulsions were necessary, but his information was genuine and had been largely provided prior to his public defection or his drunk driving arrest. Rather than the the expulsion having happened because of the drunk driving arrest, as sensational versions of the story usually allege, the expulsions happened in spite of the arrest.

The expulsions, which had been approved before Lyalin’s arrest and public defection, had been planned for October. Lyalin’s defection, and ostensibly a leak to the press (according to the UK’s explanation for not providing the U.S. with notice), had merely caused the British to move sooner than they had expected. Far from having been a lucky break prompted by a KGB officer who had been drunkenly arrested and wanted to make a deal, the expulsion was the culmination of months of effort in what was known as Operation FOOT, an effort that was equally born of counterintelligence officers and diplomatic officers.

You can read part of Lyalin’s FBI file below, or the rest on the request page.

Like Emma Best’s work? Support her on Patreon.