Declassified Central Intelligence Agency documents describe the Agency’s agreement to work with a Senator’s plan to use a 1952 Congressional investigation into Soviet war crimes for propaganda purposes. Congress was looking into the Katyn massacre in which the KGB’s predecessor’s, the NKVD, murdered thousands of Polish prisoners of war and which the Soviet Union denied responsibility for until 1990. In 1952, the Majority Leader of the House of Representatives sought to use the investigation of very real Soviet war crimes as a propaganda opportunity, and while it may have worked in the short run, documents indicate that both CIA and State Department personnel believe it may have backfired, and led to charges the U.S. was using biological weapons in Korea.

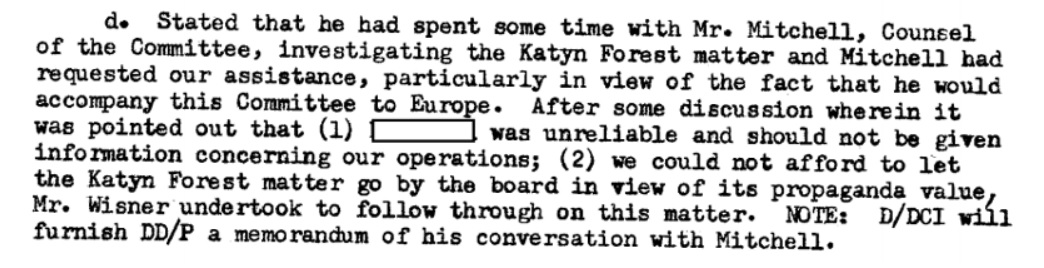

According to the formerly TOP SECRET CIA document describing the February 28, 1952 Director’s Meeting, then Deputy Director Allen Dulles was approach by John Mitchell, the Counsel of the Committee which was investigating Katyn (no relation to Nixon’s John Mitchell). Mitchell, who discussed the matter with Congressman McCormack, hoped the Agency would be cooperative with the probe to their mutual benefit.

However, those attending the Director’s Meeting had some concerns -someone whose name is redacted, likely Mitchell or McCormack, was seen as “unreliable” and not worth trusting with Agency operational details. Previously, the Agency had expressed concern that Mitchell would ask them to provide a lot of assistance with the probe. Regardless, the Agency’s senior staff decided they couldn’t let the opportunity go by “in view of its propaganda value.” As a result, Deputy Director of Plans Frank Wisner agreed to “follow through” on the matter. While a memo was apparently written from Dulles to Wisner memorializing the conversation with Mitchell, it has not yet been declassified.

Wisner had earlier recommended against working with Mitchell or any Congressional investigation. Several months earlier, Mitchell had approached Wisner when he first became the Counsel for the Committee investigation. According to a formerly SECRET memo from Wisner to the Department of State, Mitchell had approached Wisner about cooperating on the probe with no apparent mention of propaganda except a desire to avoid investigating “government officials (presumably of G-2)” who had been accused of “having suppressed certain highly relevant documents.” Wisner appropriately referred him to the Office of Legislative Counsel without commenting. In his memo, Wisner added that he did “not consider it appropriate for this Agency to become involved in Congressional investigations” - Wisner felt that was this was the Department of State’s jurisdiction.

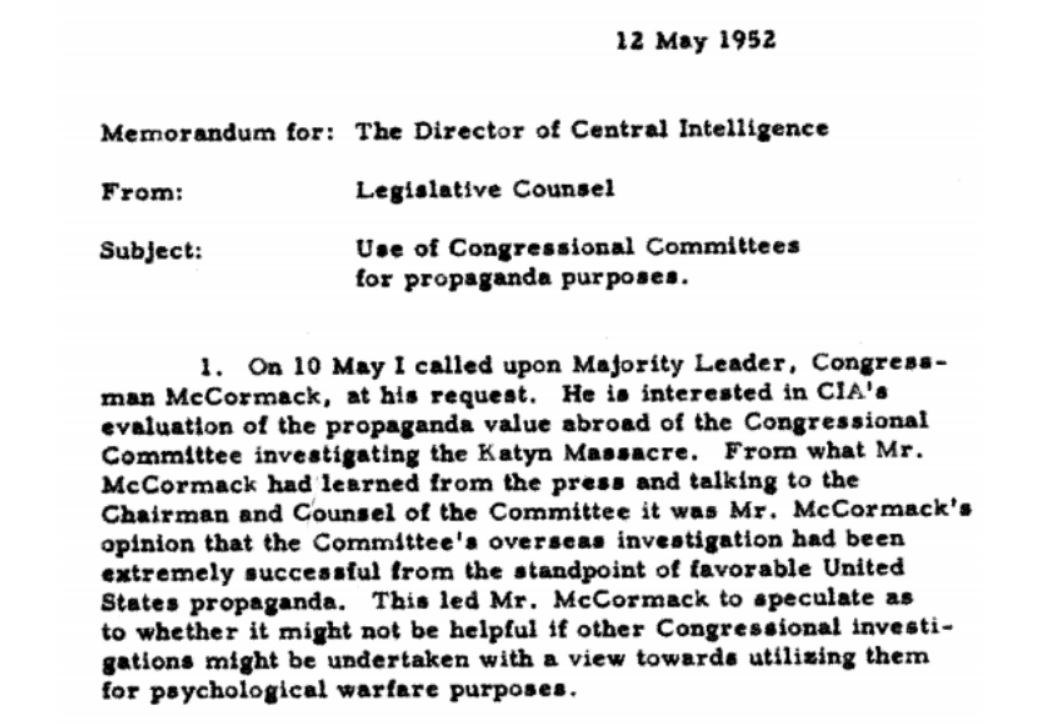

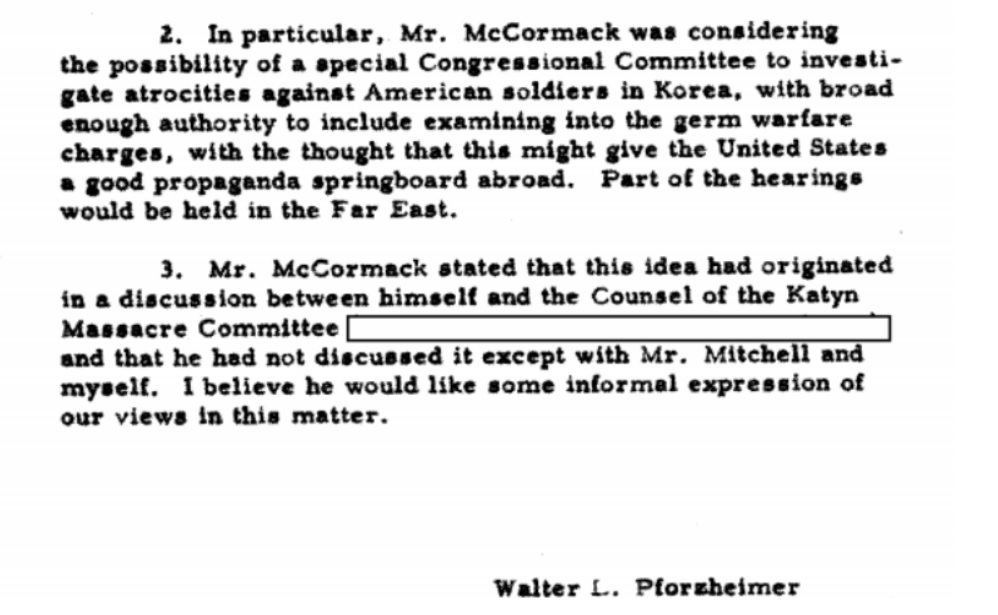

According to another formerly SECRET memo, which had curiously been referenced two days before it was written, Congressman McCormack followed up with CIA’s Legislative Counsel when the hearings had all but concluded, with only two days and five of eighty-one witnesses still to testify, to discuss the Katyn propaganda effort. While he wanted to know how CIA evaluated the overseas propaganda value of the Congressional Committee investigating the Katyn Massacre, he felt that it “had been extremely successful from the standpoint of favorable United States propaganda.”

While neither the hearings nor Mitchell’s liaising with CIA had come to an end, Congressman McCormack already his eye on the future. To his view, the effort had been more than successful enough to warrant considering doing the same thing again. McCormack openly speculated “as to whether it might not be helpful if other Congressional investigations might be undertaken with a view towards utilizing them for psychological warfare purposes.” Where the cooperation over the Katyn investigation had coalesced around an already existing effort on the part of Congress, McCormack now suggested forming new committees with that explicit expectation. In particular, he was considering “a special Congressional Committee to investigate atrocities against American soldiers in Korea, with broad enough authority to include examining into [sic] the germ warfare charges.”

In response, CIA Director General Walter Bedell Smith responded that the Agency “should have no interest in this matter.” The Director’s refusal to cooperate may have had several motivations. The first may have simply been a refusal to create Congressional investigations for propaganda purposes - using an existing investigation into war crimes as an opportunity for propaganda was one thing, but creating Congressional investigations with that purpose in mind was something altogether different.

Assuming that McCormack had meant investigating Communist use of biological weapons in Korea, then the Agency had a major obstacle to pursuing that propaganda angle. According to the formerly TOP SECRET record of another Director’s Meeting held soon after, the Agency already had a proposed propaganda plan involving Communist bacteriological warfare in Korea. The problem was that the State Department and the Joint Chiefs of Staff had disapproved of the plan since the Agency had been unable to prove there was a Communist bacteriological warfare unit in Korea.

There was another reason for the Agency to “show no interest” in the matter - some staff members of CIA and the State Department believed that the propaganda relating to the Katyn investigation had backfired. According to a formerly SECRET issue of the Current Intelligence Digest from April 12, 1952, the Italian Embassy reported that the Communist press was “continuing an intensive propaganda campaign” that alleged U.S. use of biological warfare in Korea. The Embassy believed that the campaign may have been designed “in part to draw public attention away from the investigation of the Katyn massacre.”

The Embassy and the CIA analysts reviewing their information weren’t the only ones to see such a link as plausible. A declassified Psychological Strategy Board memo written several months later describes an October 1952 conversation between John Elliott and Charles Bohlen, who was then the Counsellor to the State Department and would be named, several months later, as the Ambassador to the Soviet Union. In their discussion, Bohlen brought up the U.S.’s past propaganda against the Soviet Union. In Bohlen’s mind, the propaganda tended to be “too strident and shrill.” Bohlen believed that this resulting in alarming the U.S.’s allies more than any intimidation to the Kremlin. Worse, the “sharp attacks” reinforced the “incipient impression lurking in the minds of the peoples of the democratic world that the U.S. was a warmongering nation trying to incite hostilities with the Soviet Union.” Creating this image, Bohlen noted, was a goal of Soviet propaganda - one that the U.S. had inadvertently been helping them with.

Bohlen cited that Katyn massacre investigation as a specific example of this. He felt that the barrage of propaganda released in connection with the investigation had backfired. Like the Embassy staff members several months earlier, Bohlen felt that it “may have been responsible for the launching of the Communist bacteriological warfare charges against the United States in reprisal.”

Perhaps the Agency should have listened to Frank Wisner in 1951.

You can read additional CIA documents discussing Katyn here, the seven volumes of Congressional hearings here, the interim report here and the final report here. The Director’s Meeting memo is embedded below.

Like Emma Best’s work? Support her on Patreon.

Image by Eleanor Lang via Wikimedia Commons and licensed under Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0.