The Hart Report, also known as the Monster Plot Report, sought to affirm the Solie Report’s findings that Yuri Nosenko was a bona fide defector by denouncing the Central Intelligence Agency’s Counterintelligence Staff in general and its chief, James Angleton, in particular. Although still classified, John Hart’s report and the idea of the “monster plot” are frequently cited as examples of Angleton’s supposed paranoia and incompetence.

While Angleton and others who’d worked on the Nosenko case strongly disagreed with John Hart’s findings, they agreed him on one important point - the report was libel.

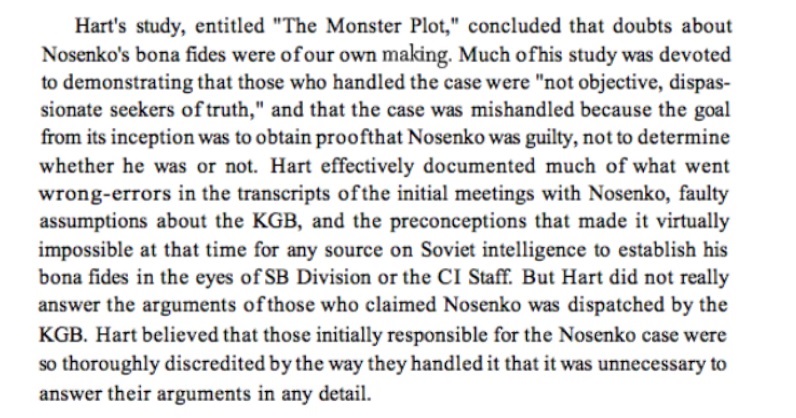

While nearly all of the Hart’s Report is still classified with a tentative release by the National Archives scheduled for later this month, and a separate FOIA request has been filed for the report, a basic summary of it can be found in Richard Heuer’s previously SECRET article, Nosenko: Five Paths To Judgment. According to Heuer’s article, “Hart did not really answer the arguments of those who claimed Nosenko was dispatched by the KGB.” Instead, Hart focused on seeing those who “mishandled” the case “were so thoroughly discredited … that it was unnecessary to answer their arguments.” Hart’s preference for this approach is corroborated in his own memos and testimony, as well as the Agency’s method for “proving” Nosenko was bona fide - rather than prove he was or prove his doubters wrong, the Agency explicitly sought to discredit Nosenko’s doubters.

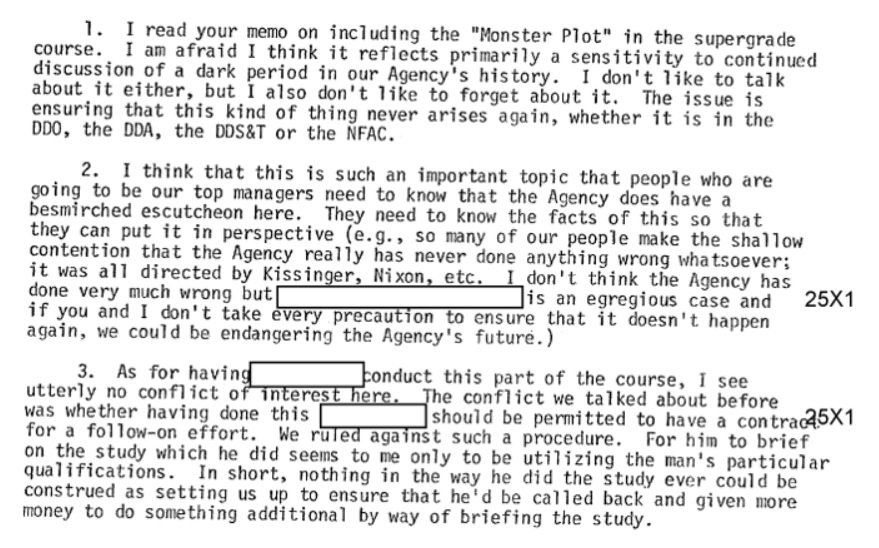

According to a formerly SECRET memo from CIA Director Stansfield Turner, the problems may have begun in April 1978 when it was suggested that Hart return to the Agency to lecture on the Monster Plot to Agency groups as part of the Agency’s training programs. Turner felt that it was an especially “egregious” case that contradicted “the shallow contention that the Agency has really never done anything wrong whatsoever” that was put forward by some Agency personnel. While the language is slightly unclear, it appears that the Agency decided against giving Hart a contract for the lectures, in part to avoid a conflict of interest.

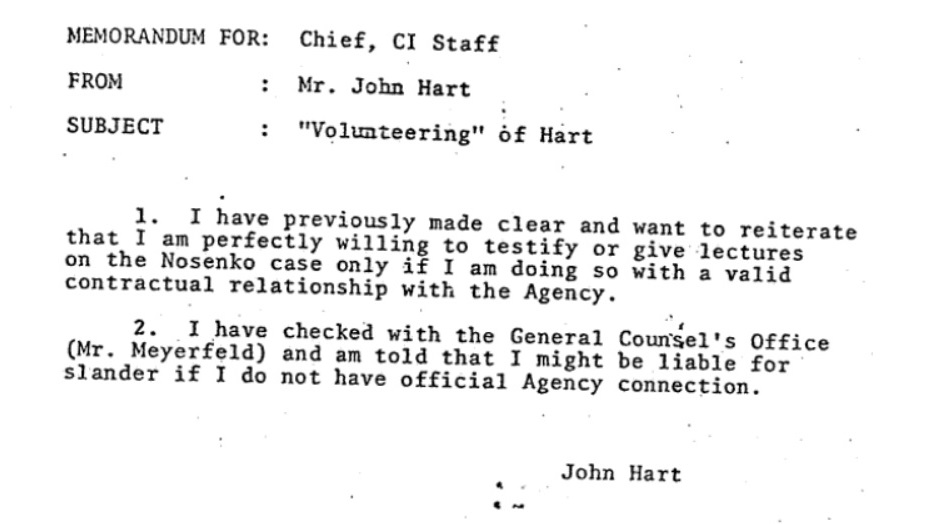

This appears to have opened the door to additional problems for Hart. While some of the documents aren’t currently available for review, the record indicates that the Agency warned Hart that giving these lectures to Agency groups about the Hart Report and the “monster plot” theory could open him up to libel charges. While the actual warning isn’t present in the available documents, declassified memos do describe it. In a memo from May 3rd 1978, Hart wrote that he had been warned by CIA’s General Counsel Office that, without a contract with the Agency, testifying before the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) or giving lectures could render him liable for slander.

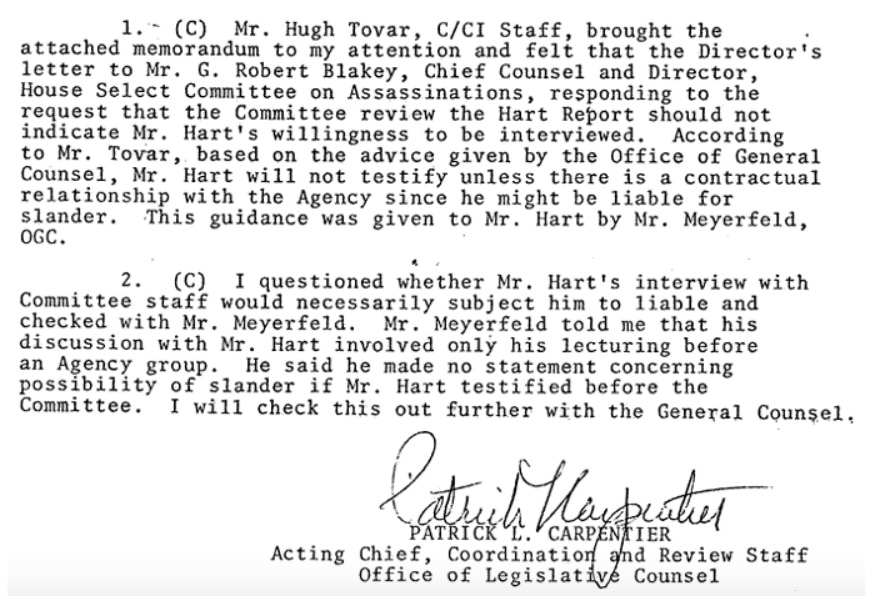

A follow-up memo from CIA’s Office of Legislative Counsel on May 15th appears to clarify matters slightly. According to this memo, The General Counsel’s office had only cautioned Hart about “his lecturing before an Agency group,” and that the possibility of slander for his testimony before the HSCA hadn’t come up.

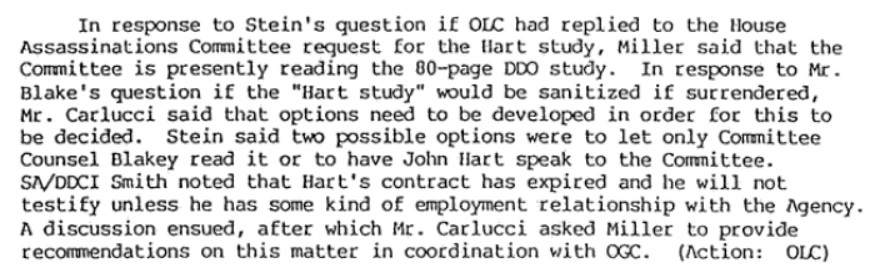

An excerpt from the DCI’s Morning Meeting Minutes for the same day shows that Hart was refusing to testify without “some kind of employment relationship with the Agency.”

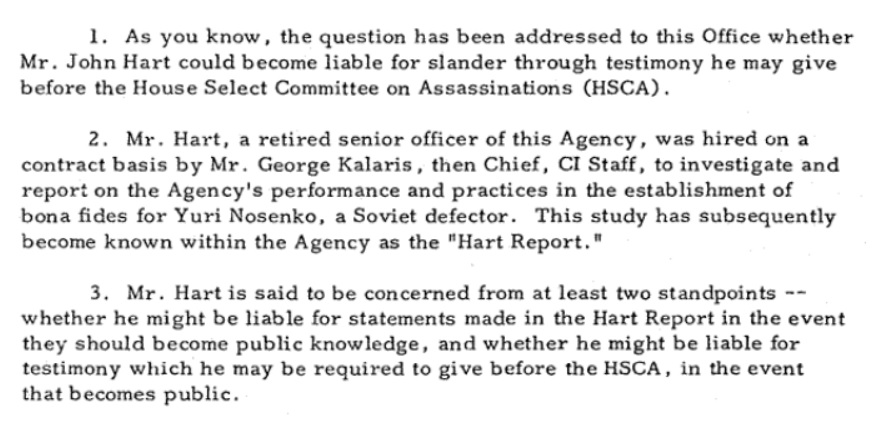

A memo from the end of the month explores the matter from a legal standpoint. According to this memo, Hart was concerned about two things: whether he would be “liable for statements made in the Hart Report … and whether he might be liable for testimony” before the HSCA.

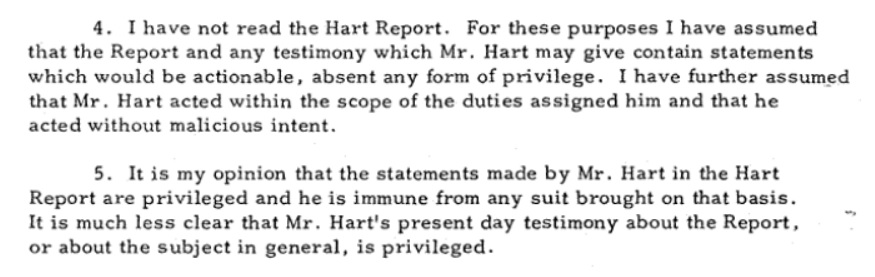

The legal analysis doesn’t consider the content of either the Hart Report or Hart’s anticipated testimony. Rather, the author of the memo admits to not having read the Hart Report and to assuming arguendo that it “would be actionable, absent any form of privilege.” Much of the remainder of the memo argues that Hart did enjoy just such a privilege, while also noting the legal weaknesses of such an argument.

While the authorship of the Hart Report was clearly done as part of a CIA contract, granting him some degree of privilege, he was “no longer a government employee but a private citizen.” While giving testimony in the present about the Hart Report could be considered “a logical extension of the doctrine of privilege,” the specific situation seemed unaddressed by case law.

More specifically, the Federal Tort Claims Act wouldn’t apply to a claim of slander. This meant that “if an action for slander were to materialize … it might be brought against Mr. Hart in his personal capacity.”

Hart’s concerned apparently remained in place, as the day before he was due to give testimony, he had sought to change his status “from an independent contractor to an Agency employee to ensure his immunity from possible libel suits.”

Hart’s concern about libel charges over his report or his testimony is somewhat ironic given that, a few weeks before raising his concerns with CIA, suggested his own libel charges. At the time, the Agency was apparently “discouraging Nosenko from filing libel or slander suits” against those who had said he was dispatched by the KGB. A memo written by Hart suggested that the Agency no longer act to prevent these lawsuits. This would have included those who published the claims criticized in the Hart Report, as well as possibly Angleton himself. This would be combined with a paper to be written and released by the Agency which would discredit the claims, which would “considerably diminish the chances of defense lawyers successfully obtaining … data in the effort to shore up their clients’ positions.”

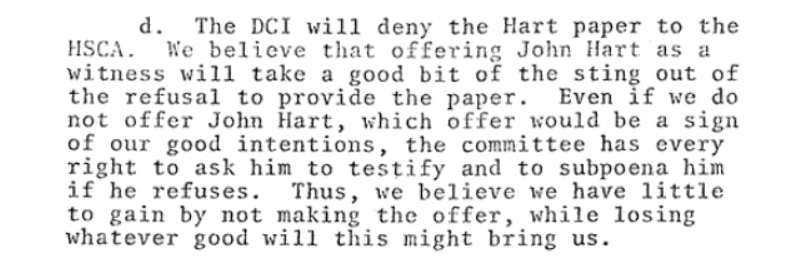

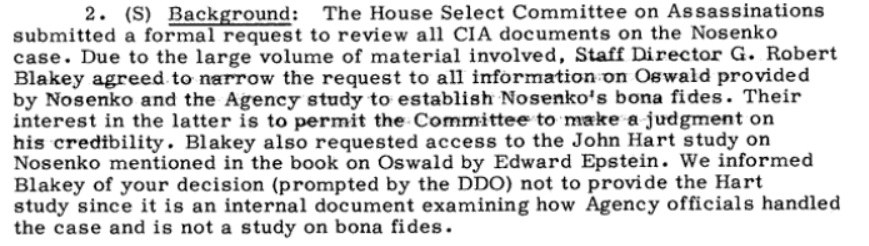

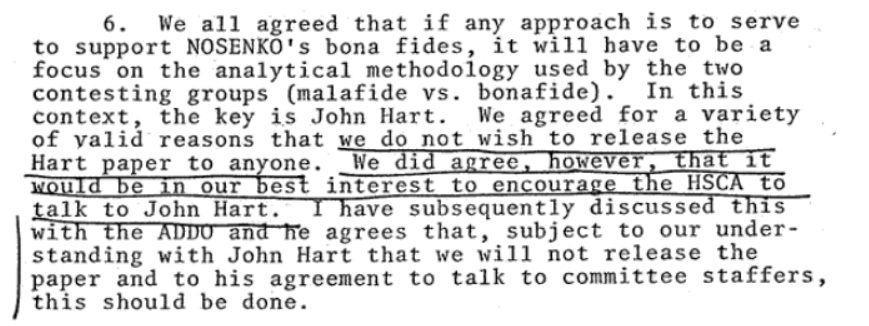

The Agency had decided not to provide the HSCA with the Hart Report, but instead to simply offer Hart to testify as a CIA spokesman under a contract with the Agency. The Agency felt that since the HSCA could simply subpoena Hart, CIA would “have little to gain by not making the offer” to have him testify.

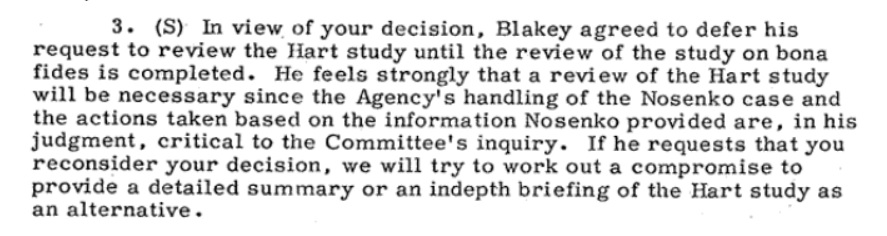

Another memo similarly indicates that the Hart briefing was offered as an attempt to prevent the Hart Report itself from being produced.

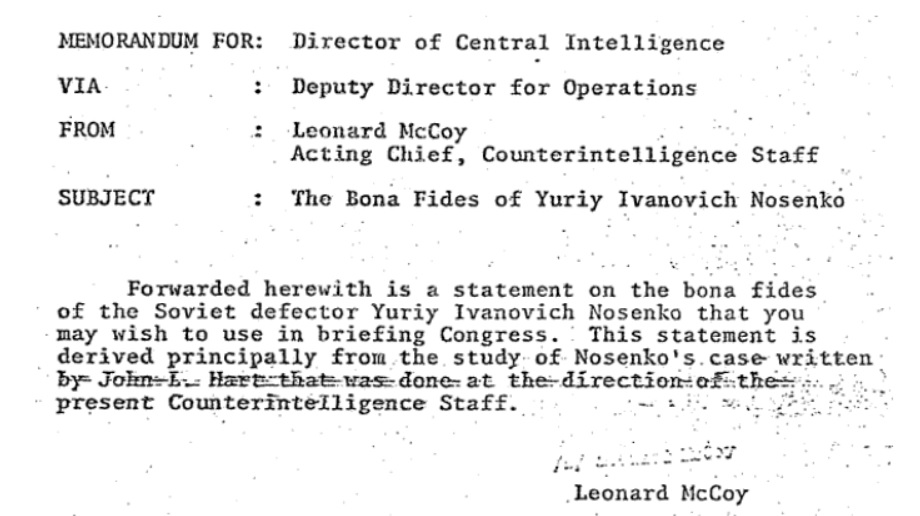

In place of the Hart Report and in addition to Hart’s testimony, CIA decided to offer a two page summary derived from the Hart Report, titled The Bona Fides of Yuriy Ivanovich Nosenko. The account presented in the summary was heavily disputed by Tennent “Pete” Bagley, who had been Nosenko’s CIA handler. Bagley later enumerated “unavoidable questions” about Nosenko, as well as a book detailing his refutations of Hart’s narrative and the reasons for doubting Nosenko.

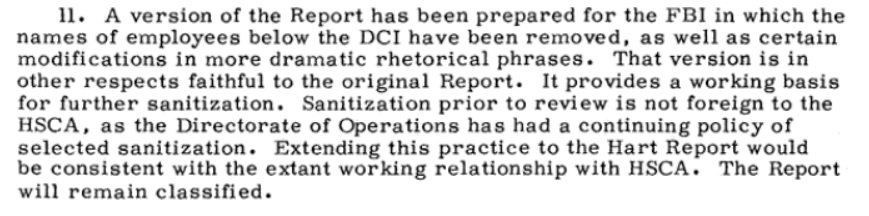

One memo shows that the Agency considered providing a sanitized copy of the report that not only removed classified information, but also made “certain modifications in more dramatic rhetorical phrases.”

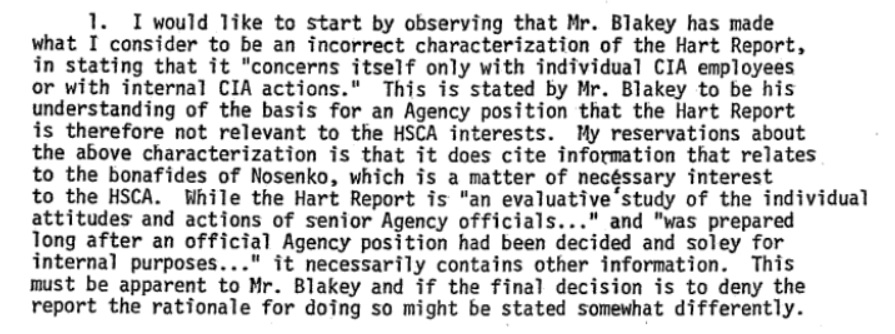

At one point, the Agency attempted to deny the HSCA access to the Hart Report by claiming it didn’t delve into the bona fides of Nosenko.

The Agency later had to admit that the logic they had provided for trying to deny access to the Hart Report was incorrect.

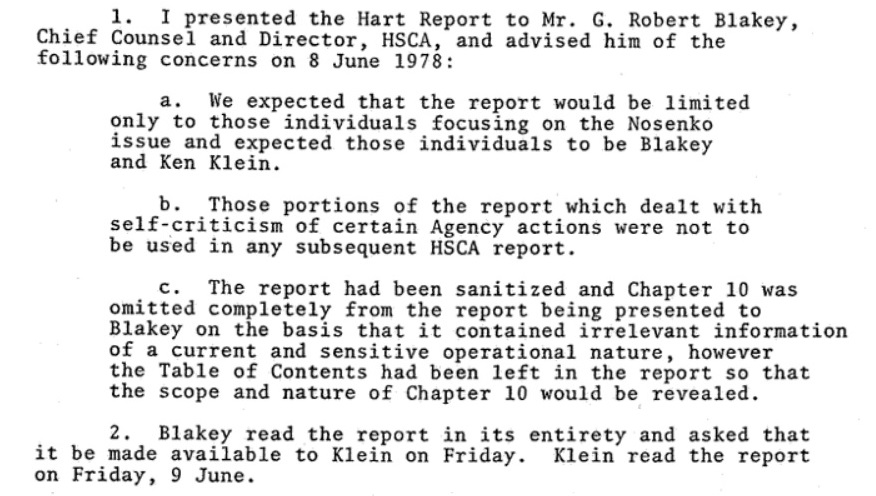

By June 8th, the Agency had conceded and provided the HSCA with a single copy of the Hart Report, with a few stipulations. The distribution of the report was to be limited, and portions of the Hart Report that were critical of the Agency weren’t to be used in any of the HSCA’s reports.

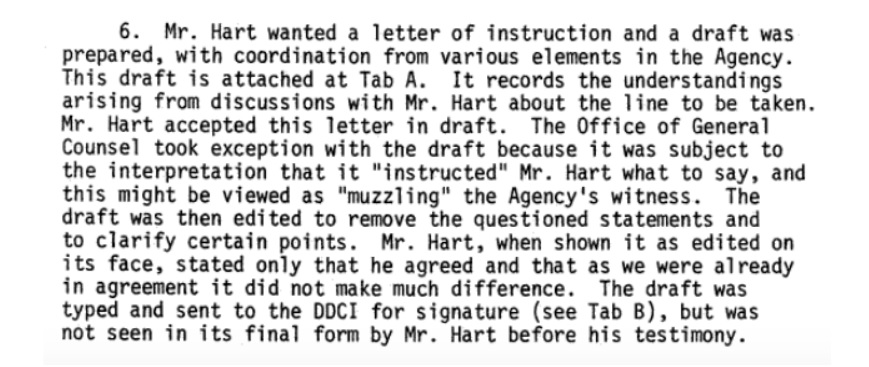

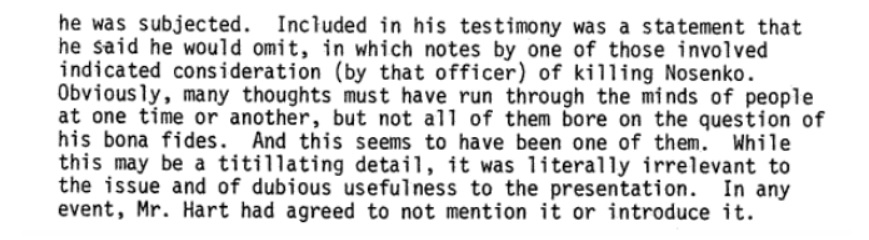

While the Hart Report was provided on a highly restricted basis, Hart’s testimony was ultimately made public and some of the Agency’s reaction to it eventually made public. Although initially concerned that the guidance they had provided Hart with would be viewed as them having “instructed” Hart or “muzzling” him, Hart was apparently unable to keep on track.

Included in Hart’s testimony was at least one thing which he promised the Agency he would omit - a reference from Bagley’s notes to the possibility of liquidating Nosenko. The Agency noted that this was “literally irrelevant” and of “dubious usefulness.” It was, however, quite standard for Hart.

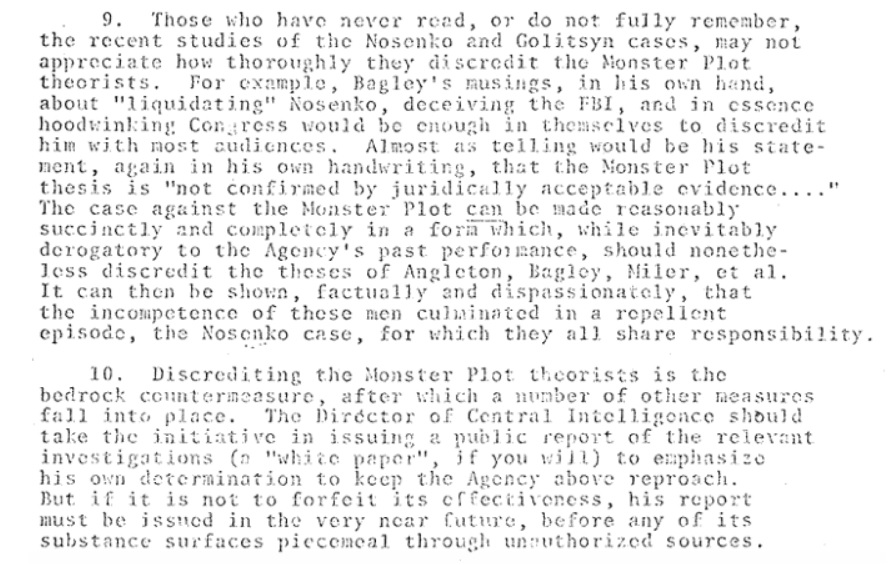

Several months earlier, Hart had suggested that the Agency use that very tactic as its strategy for dealing with Nosenko and the suspicion that he had been dispatched by the KGB. Hart felt that the cornerstone of the Agency’s strategy should be “discrediting the Monster Plot theorists,” specifically citing “Bagley’s musings … about liquidating Nosenko.” Hart felt that this and a few other details would discredit Bagley, negating any need to address his actual concerns or arguments. This would seem to conform to the description of the Hart Report cited at the beginning of this article.

This was, it seemed, the Agency’s official approach to handling the question of Nosenko’s bona fides. According to a previously SECRET memo discussing how to handle the situation, the only approach that “support Nosenko’s bona fides” would be focusing on the methodology of Nosenko’s supporters as opposed to his doubters.

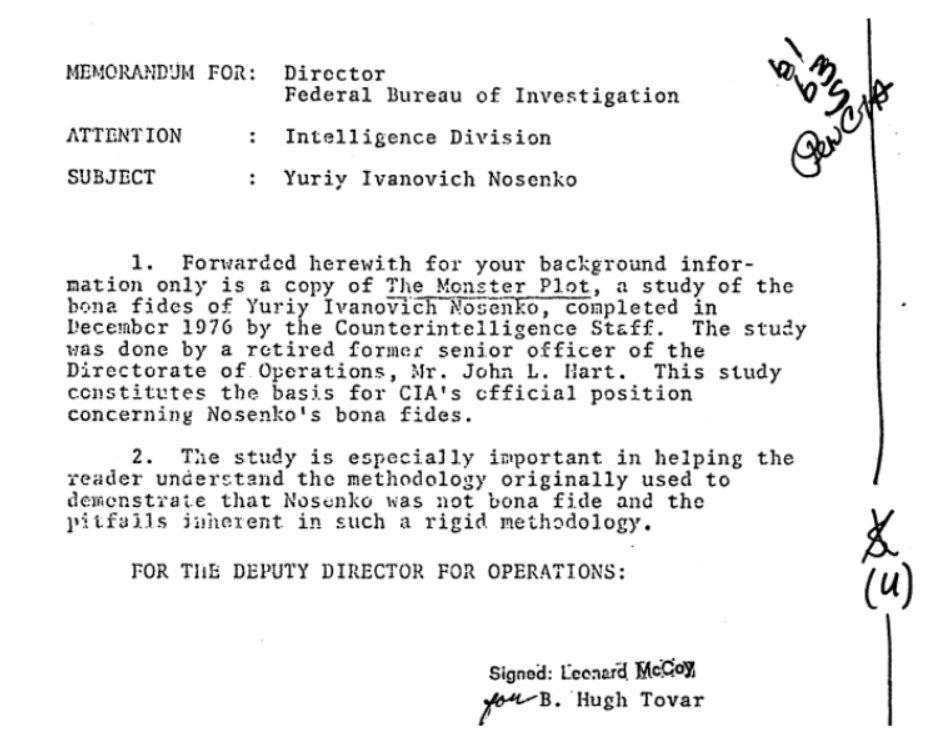

According to a memo to the FBI Director, the problem with the methodology of Nosenko’s doubters wasn’t that it was sloppy, careless or relied on faulty logic - but rather that it was too “rigid.”

Beyond attacking the credibility and methodology of Nosenko’s doubters, the Agency couldn’t seem to decide on a tactic for convincing the HSCA of Nosenko’s bona fides. According to an originally SECRET memo, they felt that it might require “a great depth of understanding” to avoid concluding that Nosenko was malafide (as opposed to bona fide). As a result, the memo recommended withholding the Hart Report (which it attempted but ultimately failed to do) while providing Hart for testimony. When it came time for Hart to testify, however, the Agency advocated the reverse approach.

A declassified memo written for John Hart providing guidelines for his testimony shows that he was advised to avoid “detailed analysis of questions.” Rather than strive for “a great depth of understanding” as the other memo suggested, Hart should opt for “a broader and more realistic frame of reference.” The goal was “to simply dismiss the finely focused and technical approach,” especially when it came to “Nosenko’s credibility as a witness on [Lee Harvey] Oswald (and thereby, indirectly, his bona fides).” This, at least, seems to match the Agency’s feeling that Nosenko’s doubters were too “rigid” in their approach.

What little evidence Hart did offer in support of Nosenko was questionable and misleading. While denouncing the information Nosenko provided on Oswald, Hart told the HSCA to focus on the things Nosenko had said which were backed up by specific physical evidence. As an example, Hart mentioned microphones which Nosenko had identified in the U.S. Embassy in Moscow. This evidence of Nosenko’s bona fides is dubious at best.

As both Bagley and Angleton noted, the microphones had been previously identified by Golitsyn, who Hart repeatedly denigrated in his papers and testimony as paranoid and of little, if any, use. That the information been previously exposed by Golitsyn, and that the physical discovery of one of the microphones would have inherently exposed all of the others is also confirmed by a declassified CIA memo. This further highlights the weaknesses with the Hart Report and his testimony. The evidence Hart offered in support of Nosenko’s bona fides and good faith provides even better proof of the bona fides and good faith of those Hart sought to, in his own words, discredit.

The only other evidence offered by Hart were a few documents, which he had promised CIA he wouldn’t give the HSCA. One of these documents was taken from Hart’s notes, and dealt with what CIA called the “literally irrelevant” list of options Bagley had written. Not only had Hart promised the Agency not to leave the HSCA with any notes or documents, he had promised not to even broach that topic. It seems that Hart, whose case revolved around discrediting people that disagreed, was unable or unwilling to resist introducing irrelevant evidence if it made them look bad.

Angleton was apparently taken by surprise by Hart’s testimony, eventually interrupting some of his initial testimony on September 22nd so that he could prepare his refutations for Hart’s claims (a number of which are refuted in Bagley’s book). Angleton returned to testify on October 5th, noting that they would have to continue the testimony later when he would answer the remainder of their questions and that Angleton. According to later letters, October 5th was when Angleton was supposedly promised access to documents he would need to respond to Hart’s testimony, though CIA’s Assistant General Counsel would deny making such a promise.

In late November, Angleton again contacted the Agency to express his displeasure about Hart’s involvement, the fact that it surprised Angleton and that Hart’s testimony was, in Angleton’s words “slanderous and perjured.” Angleton specifically objected to Hart stating that Angleton “had inspected the facility where Nosenko was held.” Despite the uncertainty of Breckinridge, whom Angleton was speaking to, Hart’s testimony did claim such a thing (Hart mistaken said “CIA Staff” instead of “CI Staff”, however, an error which Hart noted he also made elsewhere).

The accuracy of Hart’s accusation isn’t challenged simply by people like Angleton and Bagley. In addition to a refutation from other former CIA officers, CIA’s Chief Historian David Robarge lists the accusation as one of the “myths” about Angleton. Robarge notes that it’s neither historically accurate nor consistent with Angleton’s preferred M.O. Given that Hart’s testimony, and presumably the report on which it was based, contained inaccuracies and misleading information which it used in an attempt to discredit others as a primary tactic, rather than proving his case, it’s easy to imagine why the Agency and Hart had both been concerned about libel and slander lawsuits, and why Angleton now described it as slanderous.

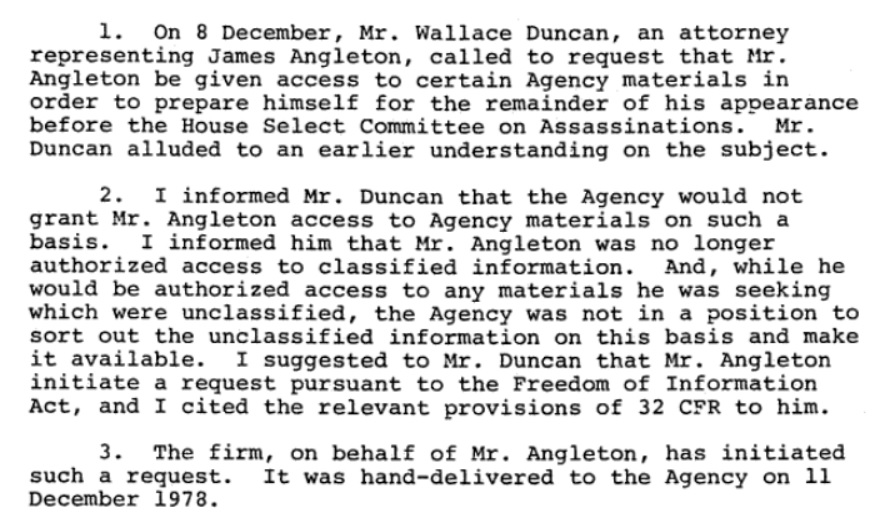

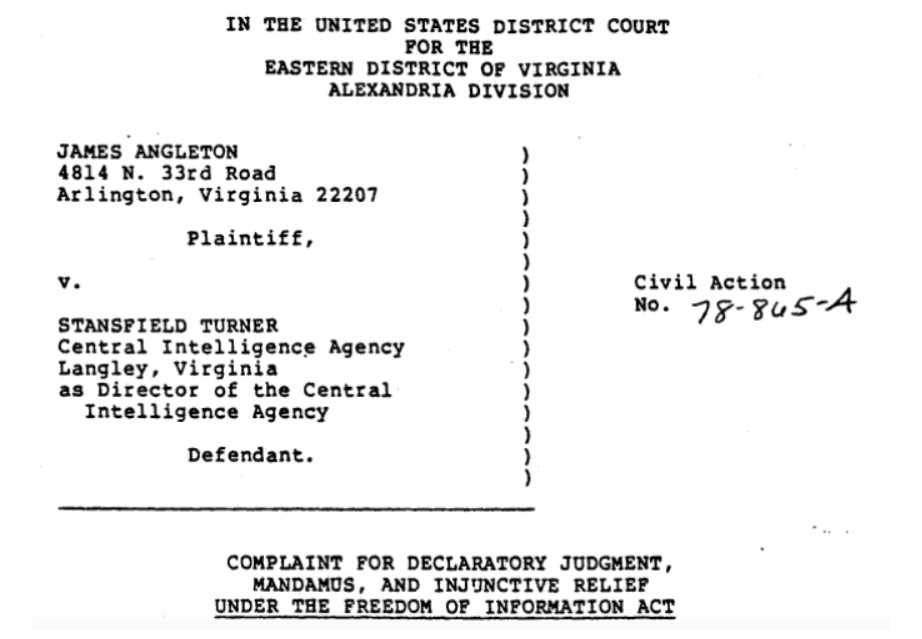

A few weeks after Angleton spoke to the Agency to express his issues with Hart’s testimony, his attorney’s reached the Agency to request access to documents to help him respond to Hart’s accusations. It was during this discussion, on December 8th 1978, that the access was officially denied and it was suggested that Angleton file a FOIA request for the documents, a request which was filed and hand delivered on December 11th.

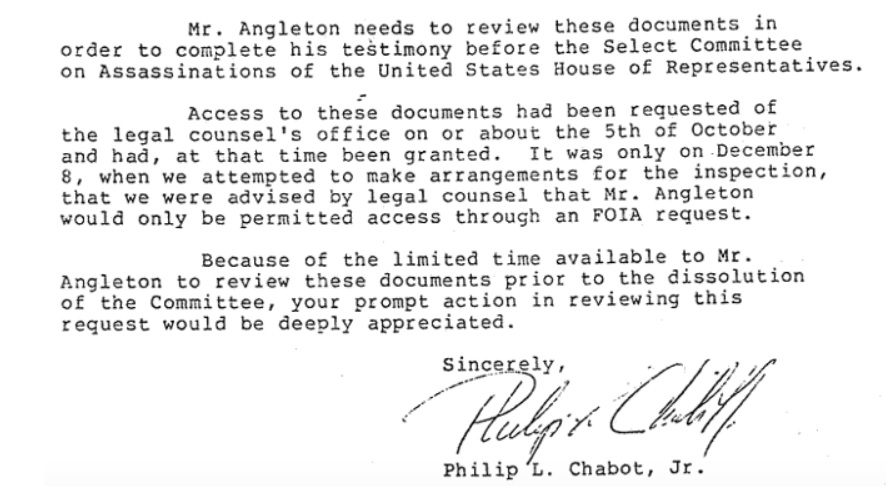

The FOIA request noted that Angleton needed the documents “to complete his testimony before the” HSCA, with the language implicitly requesting that the processing be expedited.

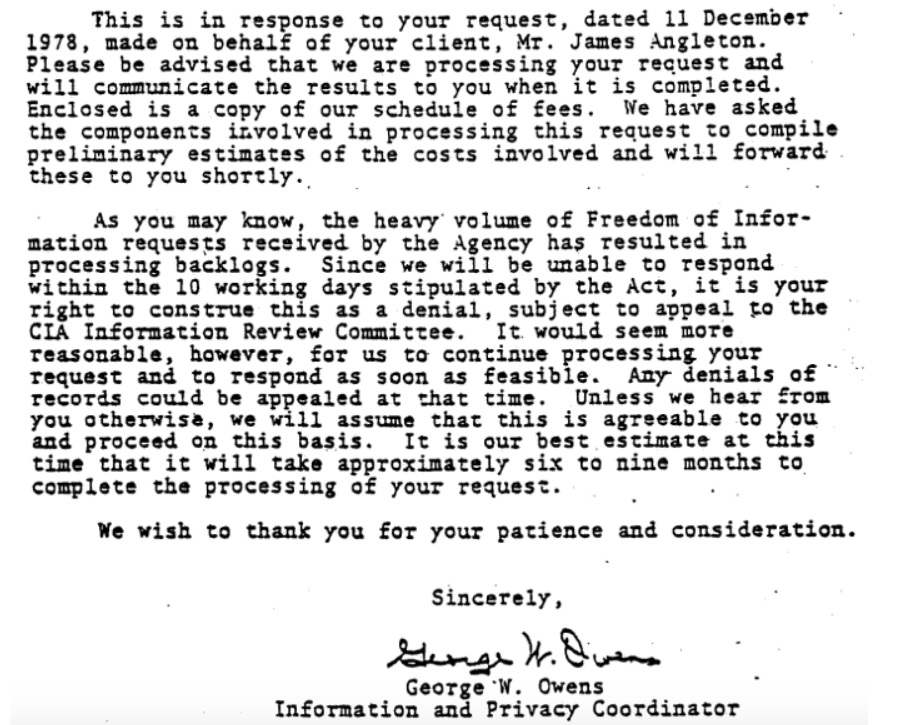

The CIA responded by informing them that they would not be responding to the FOIA request within the time period required by the FOIA statute. While the Agency admitted that this could be construed as a denial and could be appealed, “it would seem more reasonable” for them to simply wait the six to nine months that the Agency estimated a response could take. As Angleton’s attorney noted in a letter to the HSCA’s Chairman, this timeline “would make it impossible for Mr. Angleton to review the documents and complete his deposition prior to the expiration of the Select Committee.”

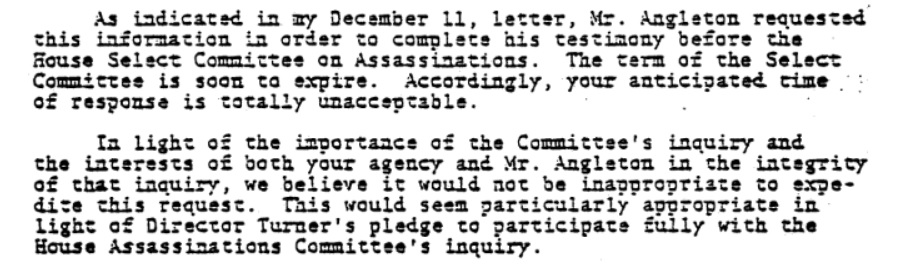

In response, Angleton’s lawyers objected and explicitly requested that the request be expedited the next day so that his testimony before the HSCA could be completed.

The attempt was apparently unsuccessful, and a few days later James Angleton, legendary spymaster and champion of secrecy, filed a FOIA lawsuit against his former Agency.

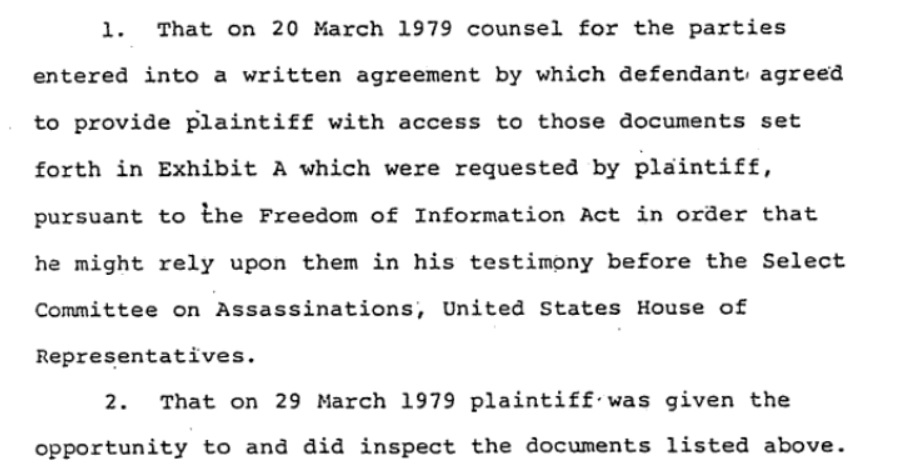

Eventually, Angleton was handed a hollow victory and his lawsuit was dismissed on April 4th the following year as part of a settlement. On March 20th, the Agency had reached an agreement with Angleton and his attorneys. According to the agreement, Angleton was granted access to the documents and reviewed them on March 29th, though they don’t appear to have been released in the traditional sense. Angleton’s FOIA victory was, however, fruitless for his HSCA testimony. The same day Angleton was allowed to review the needed documents, the HSCA Report was submitted to the full House of Representatives.

The end result was that Angleton appears to have been unable to refute Hart’s testimony. The HSCA, for its part, was unable to make a decision about whether Nosenko was a bona fide defector or a disinformation agent. They did, however, focus on the one thing that Angleton and Hart agreed on when it came to the case: not only was Nosenko unreliable, the HSCA found that “Nosenko lied about Oswald.”

Whether or not Angleton’s additional testimony and access to those documents would have helped him persuade the HSCA on the matter of Nosenko’s bona fides, the Agency’s determination to withhold the documents undermines its claims of good faith. It’s explicit tactic was to discredit Angleton, Bagley and Golitsyn by providing testimony that included what the Agency called “literally irrelevant” information of “dubious usefulness” the sole purpose of which was to attack of Bagley. The Agency felt the need to edit the “dramatic rhetorical phrases” of the report that the testimony was based on, and also warned Hart that even lecturing about the Report within the Agency could open him up to libel charges. When it came time for Hart to testify, he worried that it might be considered slander. When Angleton wanted to prove this and defend his position, the Agency did just what Hart had suggested in his initial strategy memo - they delayed and denied his access to the information until it was too late.

Angleton’s later history indicates he may have been unlikely to actually pursue libel charges against Hart or a public action against the Agency, despite some of his criticisms in the press and his attempts to defend himself. According to Senate Intelligence Committee staffer Angelo Codevilla, Angelton’s primary loyalty in the years after his public departure from the Agency remained the Agency itself - even when it was to Angleton’s detriment. Codevilla described an exchange with Angleton around 1981 when Codevilla discredited one of Angleton’s “tormentors” at the Agency. Angleton’s reaction was to call Codevilla and scold him because the man was “a pillar of CIA.”

“But he was wrong,” responded Codevilla. Codevilla also alleged that the man (who Codevilla declined to identify) was “subverting Bill Casey” and had worked against Angleton.

“No matter,” answered Angleton. In the end, Angleton’s loyalty was to the Agency. “My Agency, may it always be right, but right or wrong, my Agency!”

Regardless of Angleton’s intentions, the so-called Monster Plot report has become one of the most influential aspects of his his legacy despite not yet having been declassified. While it’s possible that the National Archives will release it in the next week, the entire release is now reportedly in flux. This report especially is likely to be contentious, as it relied not on facts or its own methodology, but misrepresentations that explicitly served to discredit others by attacking their methodology as too rigid while, per the Agency’s instructions, avoiding his own detailed analysis. Full of rhetorical phrases deemed too dramatic to share outside the Agency and “literally irrelevant” information, Hart’s report and testimony are both highly critical of the Agency and likely to spur new questions about the Nosenko case. That the report might have been libelous is simply one more reason for the Agency to want it to stay buried.

The next part in this series will examine the circumstances of Angleton’s forced public retirement in 1974 as well as how the histories around Angleton have been shaped. In the meantime, you can read some excerpts from Hart’s potentially libelous Monster Plot Report, included in his notes for his HSCA testimony, below.

Image via JFKFacts.org