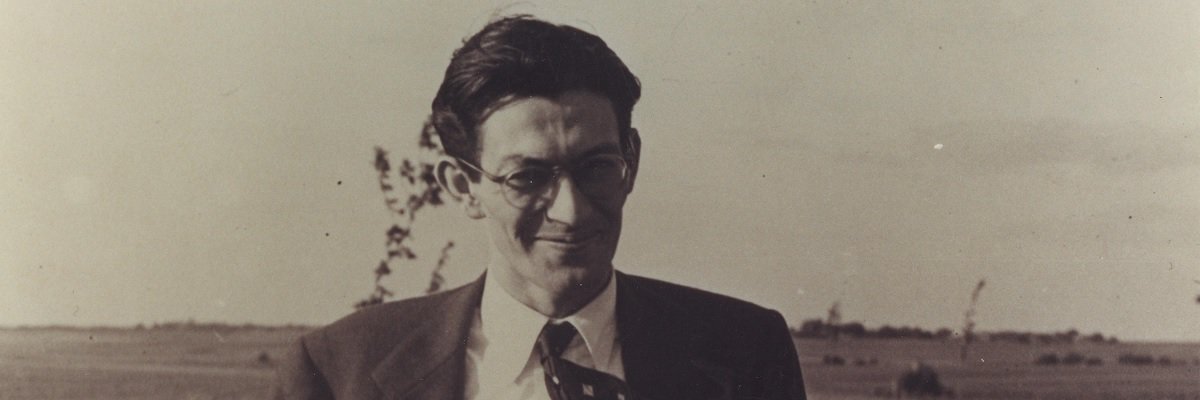

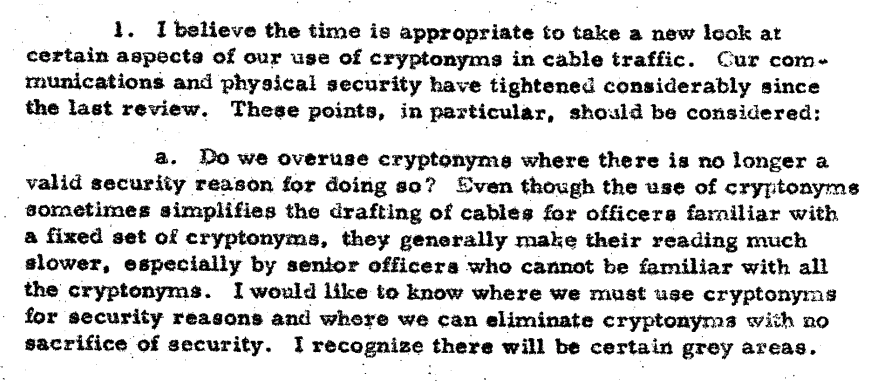

In late 1963, the Central Intelligence Agency’s Executive Director Lyman Kirkpatrick sent a memo to Counterintelligence Director James Angleton asking him to review the Agency’s perceived overuse of cryptonyms and excessive security, resulting in a report that would remain classified SECRET for 39 years.

Strangely, one reason for the request was that cryptonyms can make it harder and slower to read the materials they appear in. This, of course, is the point of cryptonyms - to make it more difficult for those unfamiliar with them to understand what’s being discussed. Kirkpatrick specifically wanted to know where they could “eliminate cryptonyms with no sacrifice of security.”

Kirkpatrick also drew attention to the Agency’s continued use of certain cryptonyms that had been compromised. This was followed by a paragraph that the Agency redacted in 2002 under 25X1, alleging that it would reveal intelligence methods.

When a copy of the document was reviewed ten years later, the Agency revealed exactly what it was that would have risked “impair[ing] the effectiveness of an intelligence method currently in use, available for use, or under development.” In this instance, the Agency’s super duper secret intelligence method was avoid potentially offending allies and other agencies by using cryptonyms that were essentially crude nicknames.

Kirkpatrick’s memo concluded with a note that not every component of the CIA was “disciplined in cryptonym procedure,” which sounds more like a management problem for the Executive Director and the Office of the Director of Central Intelligence.

The Director of Communications weighed in, pointing out that cryptonyms could make their more difficult and take more time. They also pointed out that since the cables were encrypted, there was no technical requirement to use cryptonyms in CIA cable communications. This somewhat misses the point, as cases like *The Falcon and the Snowma*n helped demonstrate.

On December 12th, ten days after the deadline set by the Executive Director, Angleton responded with a five page memo.

Angleton conceded the Director of Communications’ points, while also pointing out that a system that was secure in 1963 might not be secure in 1983 or beyond, and that the use of cryptonyms helped protect against a number of contingencies (including penetrations in the Agency and officers who are recruited by foreign intelligence services). Angleton added that the security of cables continued past their transmission. The Agency’s secrets required “constant protection and the presence of codes in the document is one way of providing a measure of security.” As many FOIA researchers can attest, the use of cryptonyms typically makes fully understanding a document harder, if not impossible. Some cryptonyms are revealed decades before its meaning is fully understood or officially confirmed.

Angleton flatly rejected the theory that cryptonyms were excessively used, citing a review conducted by the CI Staff. He conceded, however, that they were sometimes used in situations that compromised them, specifically citing the use of cryptonyms to discuss newspaper articles, or to describe the public activities of various officials.

While he acknowledged that it could cause an additional administrative load for parts of the CIA, Angleton dismissed it as secondary to the security concerns. He also pointed out that in “exceptional circumstances,” steps could be taken to reduce the administrative slowdown.

In comparison, the officers in the field were “fully knowledgeable” about cryptonyms and their meaning, according to Angleton. Security in the field needed improvement and “constant review.” Due to needing local facilities, hiring locals, and safes being penetratable, the field stations needed the protection provided by cryptonyms.

Angleton as considered the reduction of cryptonyms in communications to the field to be a point rendered moot by the recent decision to use the WALNUT system.

As for cryptonyms that were compromised and continued to be used, Angleton implied that the Agency had just given up on protecting them. Cryptonyms like KUBARK, which referred to CIA, were used so often that Angleton felt it was impossible to prevent them from quickly being compromised soon after a new one was assigned. Other than considering it a Sisyphean task, the “only” reason for continuing to use those cryptonyms remained classified in 2002.

The ultimate position of Angleton and the rest of the CI Staff was that their use of cryptonyms was fine, and that any need for improvements laid with other parts of the Agency.

A new FOIA request has been filed to learn about the Agency’s other reviews of their use of cryptonyms, and for unredacted copies of the documents cited above. In the meantime, you can read the CI Staff’s exchange below, including an early draft of Angleton’s response.

Image via CIA.gov