In the late ’60s and early ’70s, Senator Sam Ervin was working determinedly to get a Federal Employee’s Bill of Rights passed through Congress. The Central Intelligence Agency identified several areas of the bill that they felt were problematic, including how it would interfere with the Agency’s use of the polygraph as a tool to identify and terminate any “homosexual employees.”

The bill had a long legislative history and would ultimately never be passed, with the Privacy Act of 1974 eventually serving as a “compromise” bill. The Agency’s history of opposing the bill was as old as the bill itself, and had always been to request a near total exemption. On January 31, 1969, less than a month after the 91st Congress had convened, Ervin reintroduced the Federal Employee’s Bill of Rights as S. 782, “a bill to protect the civilian employees of the executive branch of the United States Government in the enjoyment of their constitutional rights and to prevent unwarranted governmental invasions of their privacy.”

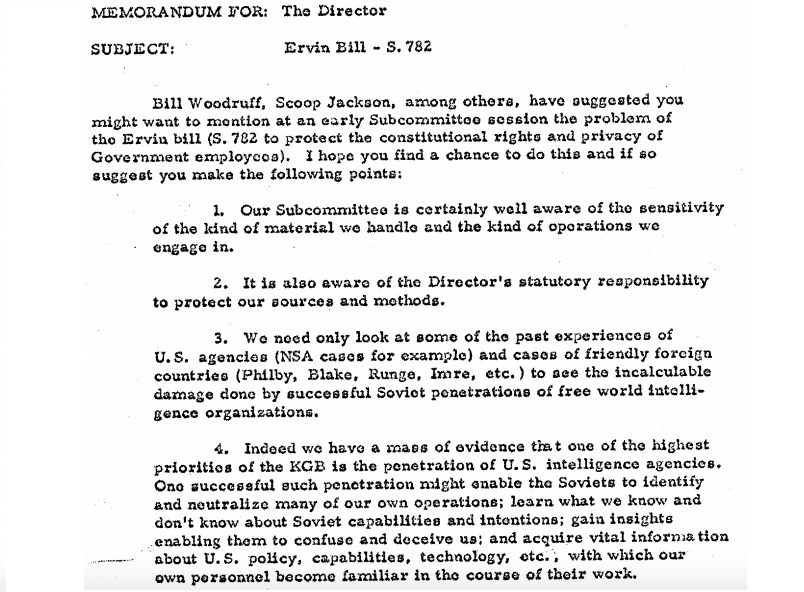

On February 21, CIA’s Legislative Counsel wrote a memo to the Director arguing against Ervin’s bill. The first page of the memo describes the Soviet determination to penetrate the Agency or any part of the Intelligence Community, as well as how damaging this could be.

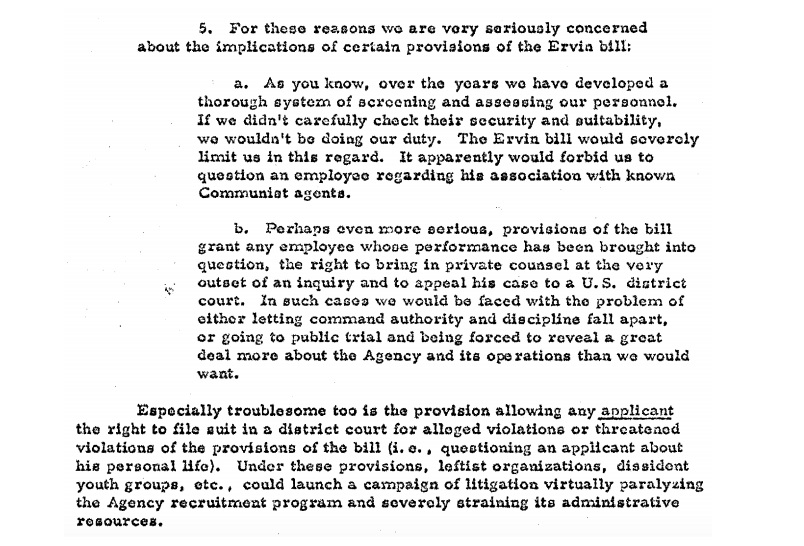

With this in mind, the Legislative Counsel felt that the bill “apparently would forbid us to question an employee regarding his association with known Communist agents.” Provisions allowing applicants to file lawsuits also seemed especially troubling.

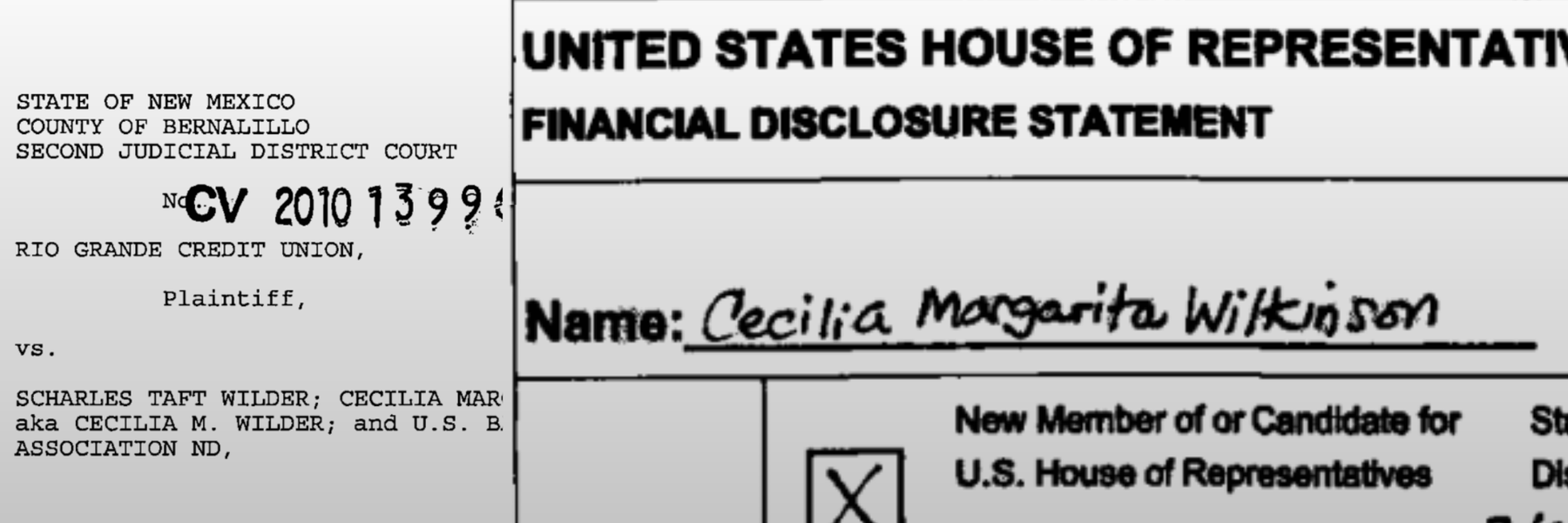

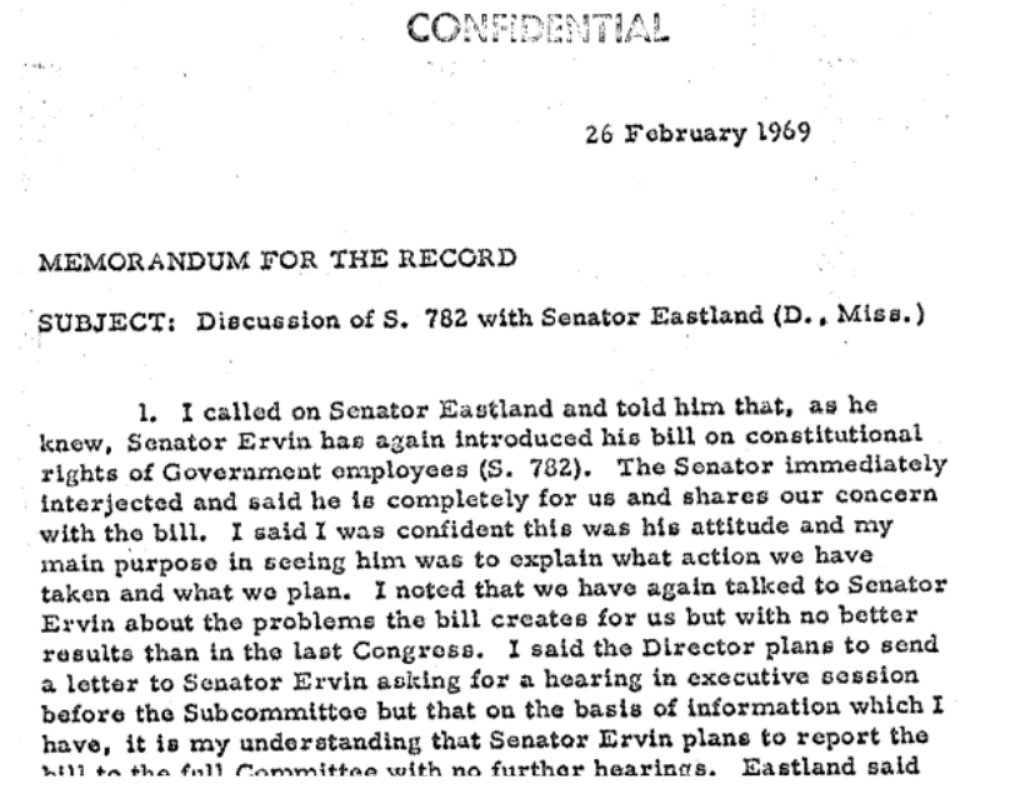

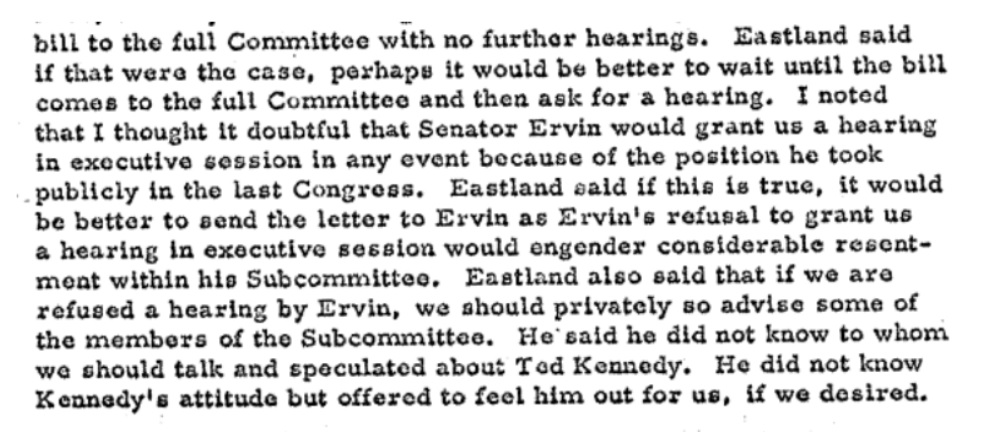

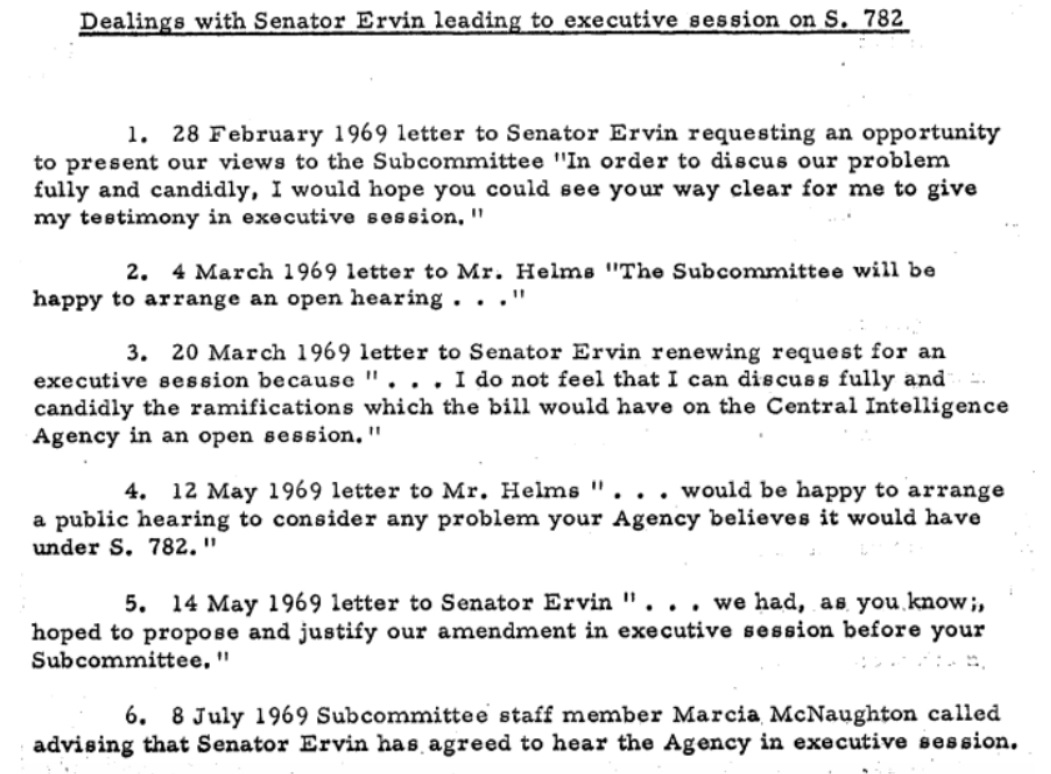

On February 26, an Assistant Legislative Counsel at CIA reported a conversation with Senator James Eastland where they discussed their mutual opposition to the bill. According to a formerly CONFIDENTIAL memo, CIA’s explicit purpose in the meeting was to explain what action they had taken and what they had planned. The Agency lawyer explained that they had spoken with Ervin, but they had as little luck in persuading him as they’d expected. The plan was for the Director to write to Ervin and request a hearing in an executive session, but they expected that it would be rejected and that Ervin would push the bill without any further hearings.

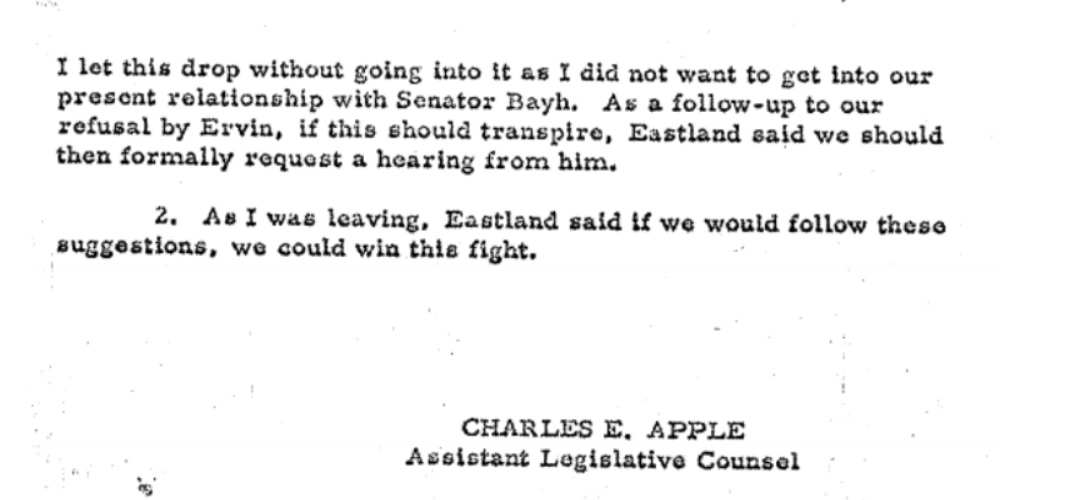

Eastland felt that if that were the case, it might be better to wait for the bill to come before the full Committee to ask for a hearing. The Assistant Legislative Counsel from CIA felt that, based on Ervin’s previous stance, they were unlikely to receive a hearing in an executive session even then. To Eastland, though, this hinted at an opportunity. If the Agency sent the letter to Ervin now and requested the executive session, then Ervin’s refusal “would engender considerable resentment within his Subcommittee.” To facilitate that resentment, Eastland suggested informing other members of the Subcommittee, offering to feel out Ted Kennedy on the subject.

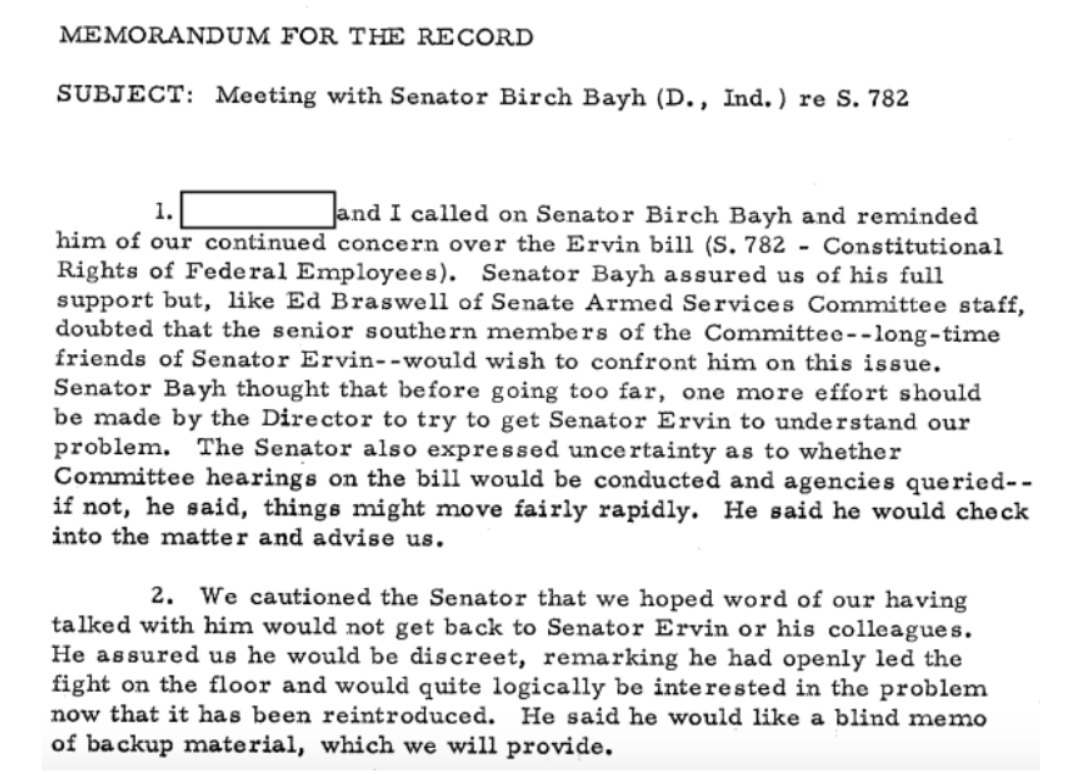

The CIA Attorney let that suggestion drop, as he didn’t want to get into the Agency’s relationship with Senator Birch Bayh. CIA had already been in touch with Bayh and were coordinating their opposition to the bill with him. As the bill progressed over the months, Bayh pushed for a complete exemption for the Agency.

If Ervin did refuse the executive hearing, Eastland suggested they formally request a hearing from him.

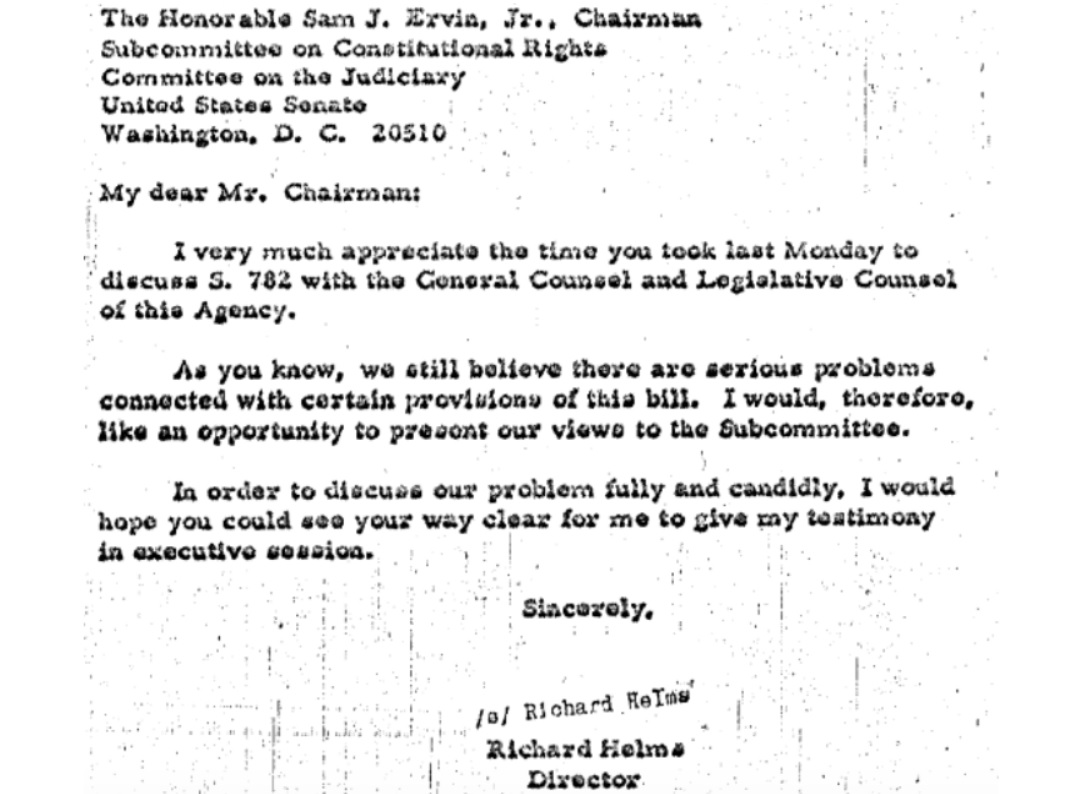

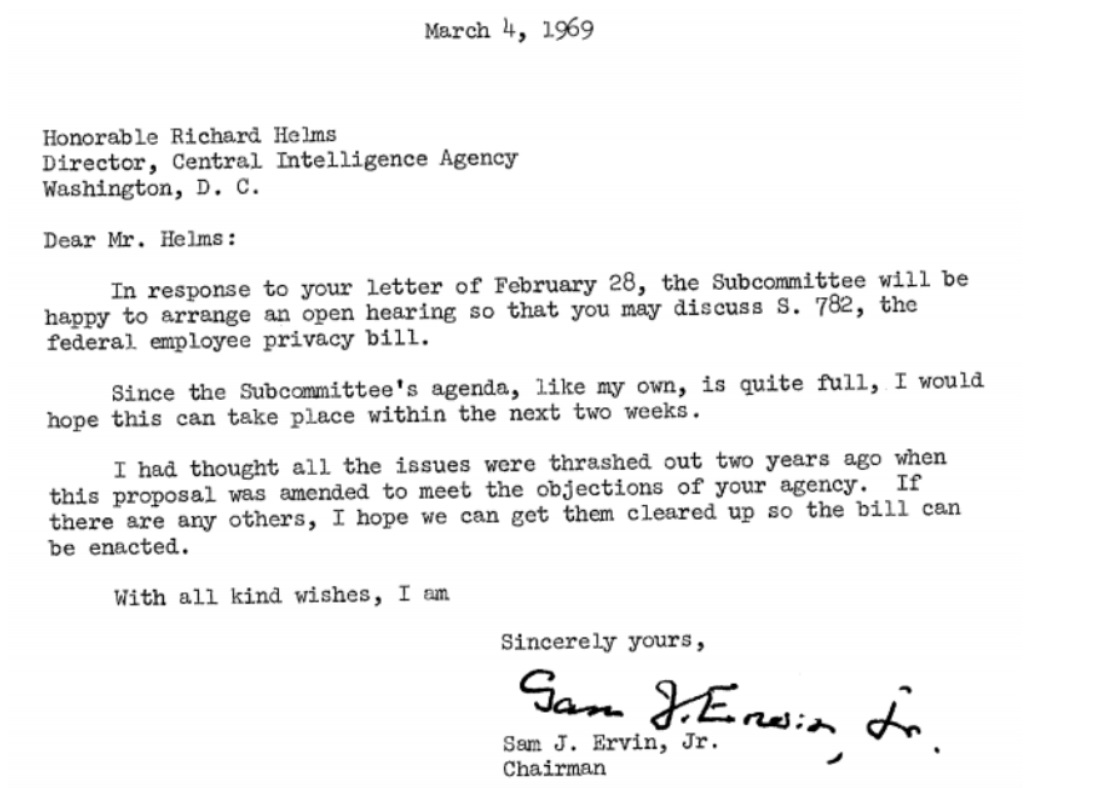

Two days later, as part of the Agency’s plan, CIA Director Richard Helms wrote to Ervin and formally requested a hearing.

The Senator responded that he was “happy to arrange an open hearing” for the Director to discuss his concerns with the federal employee privacy bill but that he hoped it could happen soon. He seemed unwilling to consider an executive session and surprised that the Agency had new issues with the bill that hadn’t been addressed with amendments from two years earlier. (It’s unclear which version Ervin was referring to, but it appears that at least one earlier version of the bill had amendments added which were not present in the current version of the bill, and which CIA would request again.)

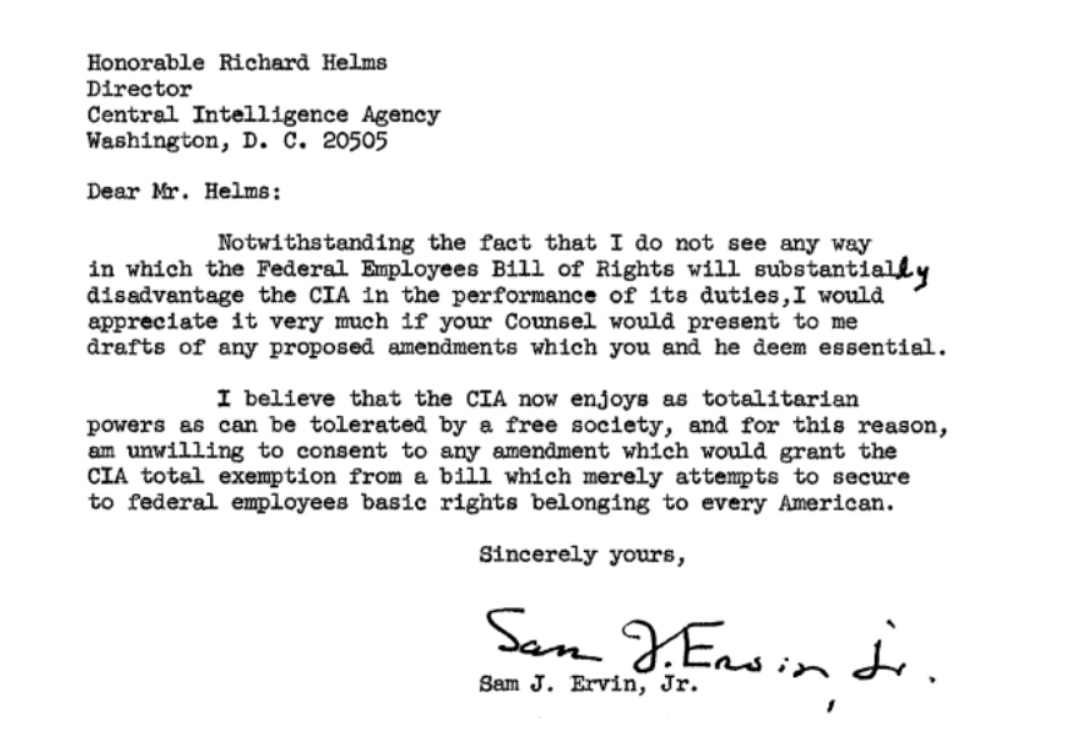

The next day, Ervin wrote to Helms again. His short letter, embedded below, is worth reading. The Senator was unwilling to grant the Agency the flat exemption that they wanted, though he was willing to consider more precise amendments to address the Agency’s concern. Senator Ervin was apparently in no mood for CIA’s request for a blanket exemption, remarking that “I believe that the CIA now enjoys as totalitarian powers as can be tolerated by a free society.”

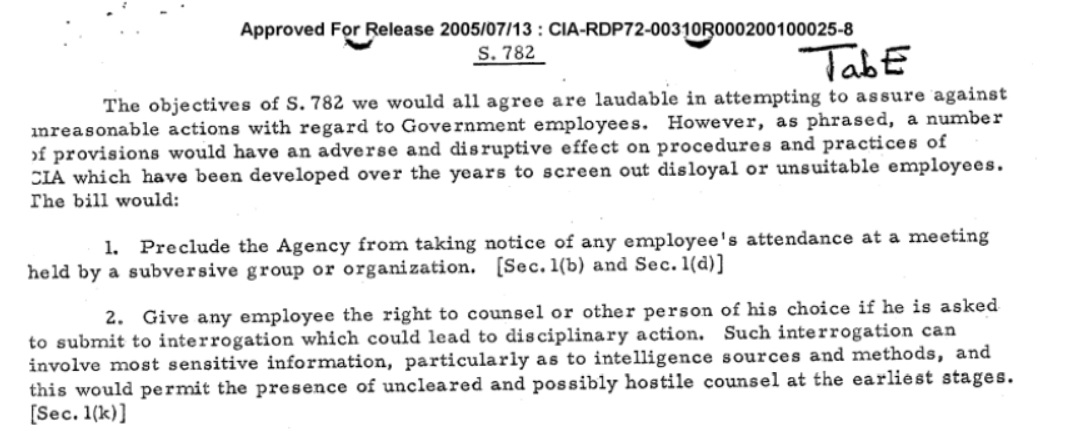

In their analysis of the bill, CIA noted a number of concerns with it, some more legitimate than others. The Agency would be unable to take notice of employees attending meetings of groups which CIA determined were subversive, and employees would have the right to counsel during an interrogation.

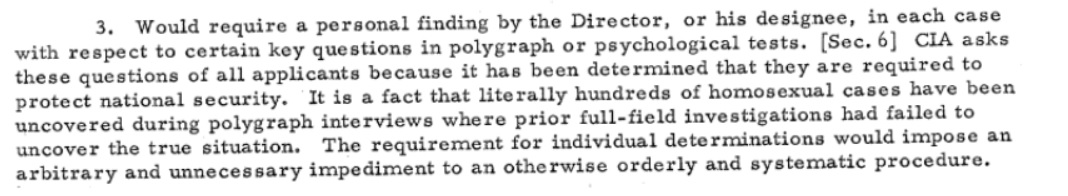

The bill would also have required approval each time the Agency wanted to ask certain questions during a polygraph exam. Some of these, such as inquiring about family history, were certainly reasonable for CIA to express some interest in when considering security clearances. A previous memo had argued that the bill would prevent the Agency from questioning employees about their association with Communists agents. However, the new paper prepared by CIA only mentioned one specific example of how they would be meaningfully limited - they would be unable to interrogate people about homosexuality.

Rather than cite the need to inquire about familial relations or the financial situation of the person under examination, the Agency stated that “it is a fact that literally hundreds of homosexual cases have been uncovered during polygraph interviews where prior full-field investigations had failed to uncover the true situation.”

While an exemption to the above was requested by CIA, it appears to have been the only area on which no compromise was reached.

The Agency also objected to the bill providing employees or applicants who accused the Agency of violating the bill to sue them in district court, regardless of whether other administrative remedies had been exhausted. The Agency described a situation in which “subversives acting on their own or on instructions from foreign agents could file suits for the sole purpose of harassment.” According to the Agency, simply filing a lawsuit would result in classified information being released. “Moreover, a campaign of leftist inspired harassing litigation would seriously burden Agency administrative resources and might virtually paralyze our recruitment program.”

While the Agency initially tried to insist on a blanket exemption to this, a compromise was agreed upon where individuals would be able to sue over violations of the bill only after providing written notice of the complaint at least 120 days beforehand, effectively forcing individuals to go through existing channels first.

The Agency also objected to the creation of a Board of Employee Rights, which would have had jurisdiction over alleged violations of the bill. The Agency’s objection essentially amounted to pointing out that there would be a conflict if the Board was investigating a matter and the CIA Director ordered employees not to release information or say anything.

In the draft of a letter, which was sent on May 14th, Helms cited only three issues with the bill. First, he felt that the right to counsel during interrogations “would permit [the] presence of uncleared and possibly hostile counsel at the earliest stages.” The second and third issues he brought up were the right to pursue relief before the Board of Employee Rights or the district court, either of which could involve the release of sensitive information. Based on these three objections, the draft letter had Helms argue for a total exemption from the bill as the most sensible and practical solution.

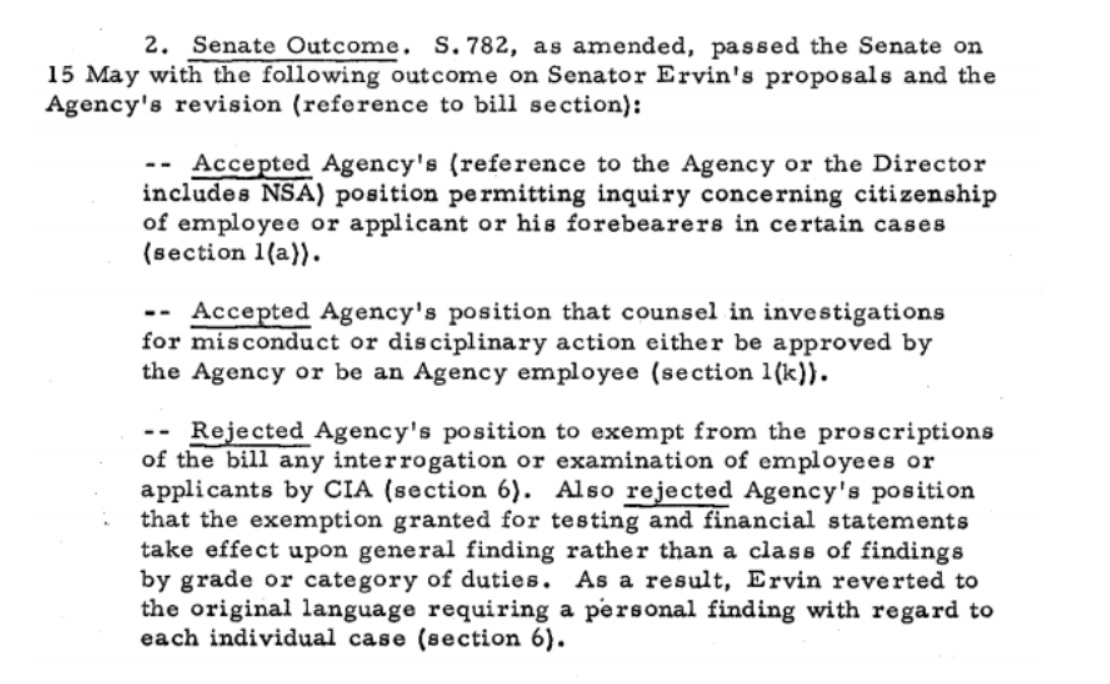

Since Ervin had requested it, however, the Agency agreed to formulate more limited proposed amendments to address their specific concerns as opposed to the blanket exemption they preferred.

The suggested amendment language produced by the Agency confirmed that they were easily able to create language which would neither impede the spirit or process of the bill nor against CIA. Instead of the blanket exemption, the new language would only deny an individual “immediate access” to the court. “It in no way interferes with his normal access to such court after exhausting administrative remedies.” It’s unclear why the Agency didn’t propose this straightforward and more practical language initially instead of requesting the total exemption, though that seems to be a knee-jerk reaction for the Agency.

A later memo noted that an executive session was ultimately agreed to in the beginning of July.

Little progress would be made, however, with expanding any of the amendments or convincing Ervin to allow the Agency to use a blanket waiver for polygraph examinations looking at financial history and searching for signs of homosexuality. Except for the polygraph amendment, a compromise was reached on the specific points CIA raised without granting blanket exemptions.

While the Agency was unsuccessful in gaining a blanket immunity to the bill, the amendments passed did grant the FBI just such an exemption. Regardless, the bill ultimately died in the House. Ervin wasn’t ready to give up on the bill, which resulted in the passage of the Privacy Act a few years later. While different in its execution, the Privacy Act addressed some of the same core concerns as the Federal Employee’s Bill of Rights did, and ultimately served as a compromise with the House’s Moorhead Bill.

You can read the packet of CIA memos on S. 782 and its predecessor S. 1035 below, or the legislative history of the Privacy Act which discusses versions of the the Ervin bill here.

Like Emma Best’s work? Support her on Patreon.

Image via Wikimedia Commons