Last week, the Justice Department released new guidelines on how its agents can use cell phone trackers in investigations. As promised, the revised policy has a warrant requirement, clear guidance on writing a detailed warrant, and provisions for deleting bystander data. Civil liberties watchdogs call it an enormous step.

But the seven-page policy hardly closes the book on StingRays. The document’s minimal best practices have no authority beyond the Justice Department. Non-DOJ federal agencies remain free to set their own guidelines on cell site simulators, as do state and local law enforcement. What’s more, agencies under the Justice Department umbrella continue to fight disclosures regarding StingRays, as they have for years. Enormous a step as it may be, this policy is but an initial one toward true transparency on cell phone tracking by law enforcement.

The guidelines come after years of press revelations, lawsuits, and Congressional hearings into how Justice Department agencies — and particularly the FBI and the US Marshals — use cell phones to locate and track suspects. Language in several sections of the policy as well the accompanying press release leave no doubt that it is a damage control measure.

“Cell-site simulator technology has been instrumental in aiding law enforcement in a broad array of investigations, including kidnappings, fugitive investigations and complicated narcotics cases,” said Deputy Attorney General Sally Quillian Yates in the September 3 statement. “This new policy ensures our protocols for this technology are consistent, well-managed and respectful of individuals’ privacy and civil liberties.”

The policy’s aim, the statement underscores, is to “enhance transparency and accountability, improve training and supervision, establish a higher and more consistent legal standard and increase privacy protections in relation to law enforcement’s use of this critical technology.”

The Justice Department emphasizes that its cell site simulators are configured solely as pen registers. That is, FBI and friends’ StingRays solely collect metadata — such as device location, numbers dialed and call length — rather than communication content. The policy thus attempts to rebut “misperceptions” that Justice Department devices vacuum up text messages and phone calls.

While it certainly aims to smooth concerned legislators along familiar “it’s just metadata” lines, the Justice Department does acknowledge use of aerial cell site simulators, one of the more controversial deployments.

Last year, the Wall Street Journal uncovered that the US Marshals use aerial cell phone trackers to hunt for fugitives. The program benefited from a partnership with the CIA, the same reporter revealed in March.

This summer, the Associated Press found a similar FBI program. The AP reported that the FBI uses cell site simulators on some surveillance overflights, which were obscured behind fictitious companies in flight registration records. Civil liberties groups worry about the sheer volume of data these flights can scoop up when combined with cell phone trackers.

Per the new guidelines, standard deployments of cell site simulators require supervisory approval. But an executive-level official must sign off in order to use aircraft-mounted devices. While the Justice Department has obliquely defended its collection practices as legal in theory, officials largely declined to confirm existence of particular practices. The latest policy guidance on using cell phone trackers aboard aircraft is one of the most direct acknowledgements to date.

Such newfound frankness on aerial cell phone tracking, not to mention the policy’s copping to cell site simulators used across the Justice Department, is a monumental step itself. The new guidelines also require agencies to keep basic statistics on cell simulator use, including the total number of times they’re used in a particular jurisdiction and the number of deployments to support investigations conducted by other agencies, including state and local law enforcement.

That we don’t have these figures already is unacceptable, as they are critical in evaluating the extent to which StingRays are deployed. The Justice Department asserts that cell phone trackers are “deployed only in the fraction of cases in which the capability is best suited to achieve specific public safety objectives.” Let’s see the numbers, then.

The Justice Department says that the policy’s foremost aim is to “enhance transparency and accountability.” Federal officials need not look far to find the troublespots on this front. It took a FOIA lawsuit to get nearly 5,000 pages of documents out of the FBI, and then additional litigation to remove redactions of references to the Harris Corporation and even the term “StingRay.”

The FBI continues to issue “neither confirm nor deny” rejections for basic cell phone tracker documentation, including paperwork required under its nondisclosure agreements with state and local agencies. In the past month, the Justice Department has upheld two such blanket rejections by the FBI.

Transparency itself requires enforcement and rigorous testing. Let’s see the documents, too.

To fully assess how and when police track cell phones, federal measures are insufficient. The guidelines cover instances where the FBI or another component deploys a cell site simulator on behalf of a partner agency, but its authority does not extend beyond the Justice Department.

“The various DOJ components are some of the more responsible users of StingRays,” Nate Cardozo of the Electronic Frontier Foundation contends. But other federal agencies and the dozens of state and local have no restrictions under this policy, nor transparency obligations.

Disclosures from the Tacoma Police Department and other non-federal agencies have helped fill gaps in public knowledge about cell phone tracking, particularly regarding the nondisclosure agreement signed with the FBI as a requirement to purchase a StingRay. But other state and local agencies continue to withhold basic information. Police in Boston, for instance, argue that releasing any documents on StingRays would render the technology “essentially useless for future investigations.” The Indiana State Police, for its part, cites risks of terrorism — both standard and agricultural — to swat down inquiries.

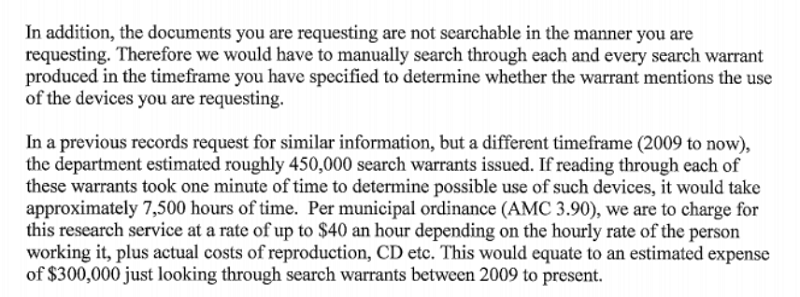

Like their federal partners, many state and local agencies are not keeping basic statistics on StingRay deployments. Last week, police in Anchorage rejected a request on the grounds that they would have to “manually search through each and every search warrant […] to determine whether the warrant mentions the use of the devices.” We need to know how often StingRays are used in the wild and on what types of investigations, and not just by FBI agents.

The Justice Department policy now requires more detailed explanations to the court when requesting authorization for cell phone trackers. State and local have no such obligation. Judges have called out police and prosecutors alike for failing to adequately describe StingRay technology in their requests. In Baltimore, thousands of cases may require review following claims that prosecutors and police withheld information on cell phone tracking.

In short, this is not solely a federal issue. It will take state-level measures, such as the one Washington passed in May, to extend transparency on cell phone tracking to non-federal law enforcement, as well as continued investigation into how such agencies have used StingRays.

Nate Wessler of the ACLU suggests that the Justice Department could leverage its position as a funder where state or law agencies use federal grants to purchase cell site simulators.

“It should be a requirement of that grant that these protections travel along with money,” he says. “A local agency shouldn’t be able to flout these minimum protections just because they’re using federal money rather than using federal equipment itself.”

It is unclear whether such a mechanism is being considered by the Justice Department. In 2013, the DOJ agreed to modify equipment grant guidelines following a finding that there was insufficient monitoring of funds given to state and local agencies to purchase drones. Unmanned aerial vehicles were added to the list of “controlled” equipment for which applicants must submit additional justification. Cell site simulators are not currently in this category.

The basic protections and disclosure obligations established by the Justice Department guidelines are a beginning. They are a minimal standard for assessing the FBI and other Justice Department components’ deployment of StingRays, as well as a minimal bar of transparency and disclosure for non-federal agencies that use these devices. And they are a milestone on a much longer path toward understanding how the government balances privacy and public safety.

Read the full policy below, as well as additional analysis by the Electronic Frontier Foundation:

This piece is part of the Spy in Your Pocket Project

Image via this request.