The Drug Enforcement Administration has at least two systems that can locate an individual mobile device to within 25 feet, the agency admitted recently. Meanwhile, just down the halls of the Justice Department, the FBI insists that it can neither confirm nor deny that it has any records on the same system.

The KingFish is part of the StingRay family of cell phone trackers, which are manufactured by the Harris Corporation. By mimicking a cell phone tower, the KingFish allows its user to triangulate the location of all phones within range based on signal strength.

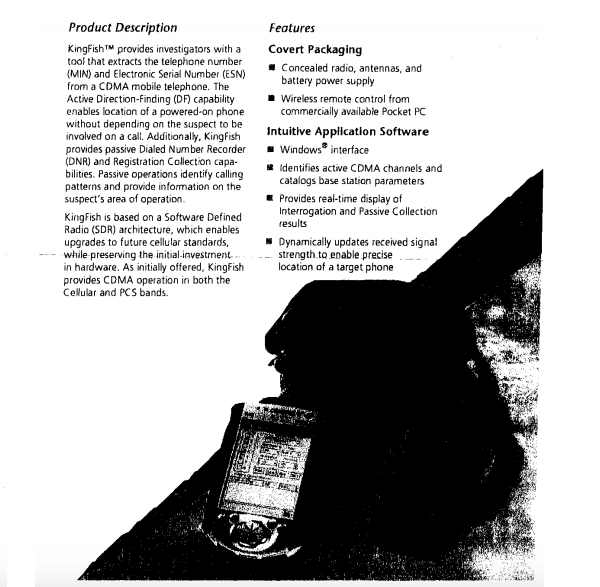

Harris Corporation markets the KingFish system for its portability, covert packaging and simple user interface. The KingFish is also designed for precision.

According to marketing materials sent to potential government clients, the KingFish system can be mounted on a vehicle, carried by hand or worn by the user. As of 2010, the KingFish retailed at around $28,000.

A phone does not have to be in use for a KingFish to track it.

“The Active Direction-Finding (DF) capability enables location of a powered-on phone without depending on the suspect to be involved in a call,” reads one KingFish brochure. “Passive operations identify calling patterns and provide information on the suspect’s area of operation.”

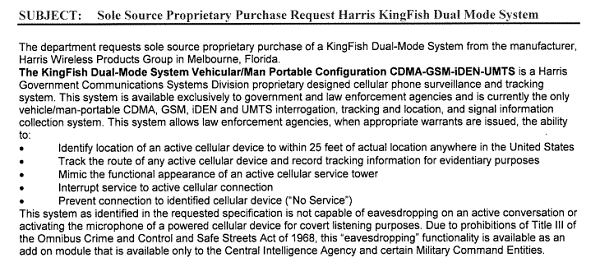

According to a 2009 purchasing memo from the Anchorage Police Department, a KingFish can locate “an active cellular device to within 25 feet of actual location anywhere in the United States.”

The system can also block mobile devices’ network connection. Anchorage police thus pitched their KingFish purchase for twin purposes: “to remotely disarm a cellular triggered explosive device and to identify the location or [sic] terrorist suspects and track their movements.”

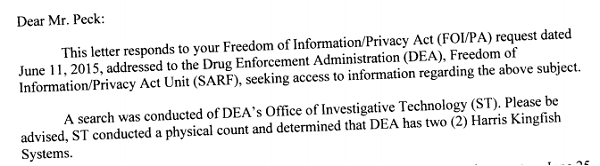

In response to a Freedom of Information Act request submitted by MuckRock user Martin Peck, the Drug Enforcement Administration acknowledged earlier this month that it has two KingFish systems.

“Please be advised, [the DEA’s Office of Investigative Technology (ST)] conducted a physical count and determined that DEA has two (2) Harris KingFish systems,” the DEA wrote in its July 2 response letter.

MuckRock has requested all invoices and other purchasing documents for the DEA’s twin KingFish, as well as policy documents that dictate how DEA agents deploy them.

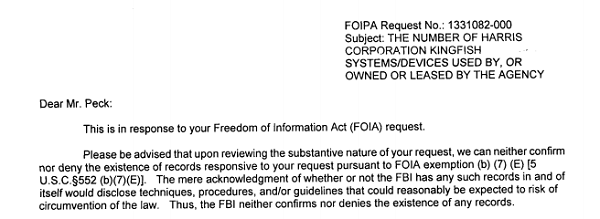

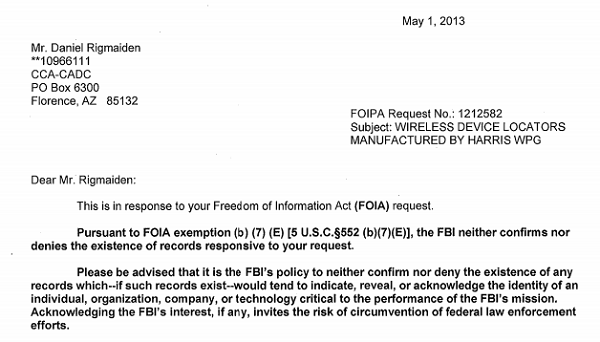

But the FBI rejected an identical request for a count of KingFish systems in its inventory.

The bureau’s records office claims that it can “neither confirm nor deny the existence of records” that would respond to Peck’s request. Such a response is called a Glomar rejection.

“The mere acknowledgement of whether or not the FBI has any such records in and of itself would disclose techniques, procedures, and/or guidelines that could reasonably be expected to risk of [sic] circumvention of the law,” the FBI wrote in a July 6 letter.

The FBI has trod this “neither confirm nor deny” path before on cell phone trackers. The agency has lost that fight, to the tune of nearly 5,000 pages released so far.

In 2011, Daniel Rigmaiden filed a FOIA request to the FBI for documents on deployment of cell phone trackers - including KingFish - during the agency’s investigation against him for tax fraud charges. Eighteen months and a lawsuit later, the FBI likewise told Rigmaiden that it could neither confirm nor deny whether it had documents on Harris Corporation devices.

“Acknowledging the FBI’s interest, if any” in such cell phone tracking technology, the FBI argued to the judge, “invites the risk of circumvention of federal law enforcement efforts.”

Rigmaiden supplied the court with hundreds pages of public documentation of the deployment of Harris Corporation devices. His filing included FBI disclosures that its agents had used Harris Corporation products during investigations.

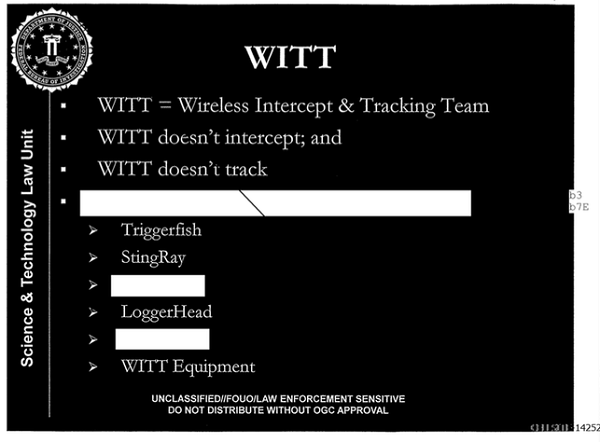

The FBI then reversed course and agreed to reprocess thousands of pages of documents and remove redactions of certain words. The FBI specifically vowed that it would no longer redact such keywords as “stingray” and “Harris Corporation”, as well as “Triggerfish” and “Loggerhead”, two other models in the StingRay line of cell site simulators.

But the FBI continues to redact and “neither confirm nor deny” other cell phone tracking equipment. There is not a single mention of KingFish in the 5,000 pages released pursuant to Rigmaiden’s lawsuit, a copy of which was also released to MuckRock.

The agency’s latest response suggests that the FBI will revisit transparency skirmishes it has already lost. Given attention from the public and Congress on the matter of cell phone tracking by law enforcement, the FBI’s model-by-model veil cannot hold.

Image via Wikimedia Commons