Last month, the Massachusetts public records chief ordered the Boston Police Department to release documents on StingRay cell phone trackers, or else provide a more detailed rationale for withholding them. The ruling came in response to an appeal filed by Mike Katz-Lacabe, a researcher in California who is conducting nationwide inquiries into cell phone tracking by law enforcement.

In January, Katz-Lacabe filed a request to BPD for cell phone tracker acquisition documents and non-disclosure agreements. The department rejected his request in full with template denial language in February. Upon appeal, the state records authority deemed BPD’s response insufficient, and on May 13 gave BPD ten days to provide more thorough justification.

In a letter dated May 19, BPD offered another glimpse into its position regarding cell phone trackers and transparency obligations.

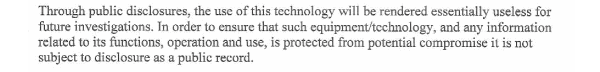

Releasing the requested records, the department argues, would not only “reveal sensitive technological capabilities” that BPD and law enforcement agencies employ, but might also “allow individuals who are the subject of investigation […] to employ countermeasures to avoid detection.”

“Additionally, the information contained within the requested documents could be used to construct a map or directory of jurisdictions that possess the investigative capabilities, thereby providing further information for potential suspects that could be used to evade detection.”

A department lawyer summarized that releasing documentation would render cell phone tracking technology “essentially useless for future investigations,” and that protecting investigative capabilities requires police to withhold these records in full.

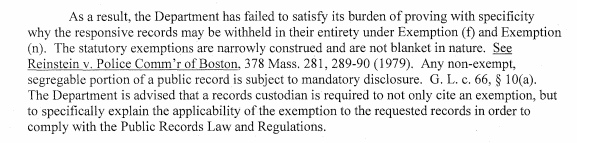

Notably, BPD dropped one of the two exemptions invoked in its initial denial: the department’s May 19 letter makes no mention of exemption (n), which covers documents that are “likely to jeopardize public safety” if released.

The state public records supervisor previously chided BPD for invoking the public safety exemption without any explanation whatsoever.

“With regard to Exemption (n),” the state pointed out in its determination, “[the department’s] response merely cites the exemption and does not address the security-related rationale needed to justify withholding records under this exemption.”

“The Department is advised that a records custodian is required to not only cite an exemption, but to specifically explain the applicability of the exemption to the requested records.”

BPD’s latest letter continues to argue that StingRay documents are exempt from disclosure under exemption (f), which protects investigatory materials.

Mr. Katz-Lacabe has already filed a subsequent appeal to the state. He contends that his request for fiscal documents and non-disclosure agreements — which all state and local law enforcement agencies are required to sign with the FBI prior to acquiring cell phone tracking devices — do not qualify as investigatory materials.

“None of the above documents contain information about the technical capabilities of the equipment used by the Boston Police Dept., how the equipment is used, under what circumstances the equipment is used or how frequently it’s used,” he wrote in his June 6 appeal.

BPD has denied two of MuckRock’s requests for StingRay documents. Word for word, both rejections used the same broad language that the state deemed insufficient upon Katz-Lacabe’s appeal.

The department has yet to issue a determination for a third request for StingRay documents, which MuckRock submitted in early April. Given BPD’s delay in answering my most recent request, I will be appealing to the state public records supervisor on grounds of constructive denial. Follow the request for updates.”

Image by Paul Keleher via Wikimedia Commons and is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0