Last week, the Massachusetts public records chief determined that the Boston Police Department must either release documents on StingRay cell phone trackers, or else provide a more detailed rationale for withholding them.

In February, Boston police rejected in full a request for StingRay non-disclosure agreements. State and local law enforcement agencies are required to sign such an NDA with the FBI prior to acquiring cell phone tracking equipment.

The request was filed in January by Mike Katz-Lacabe, a researcher based in California who is conducting nationwide research into cell phone tracking by law enforcement. He also sought standard contract documents, as well as reports that the department must file with the FBI if it has signed the StingRay NDA.

BPD invoked two provisions under the Massachusetts public records law to deny Katz-Lacabe’s request in full: exemption (f), which protects investigatory materials, and exemption (n), which covers documents that are “likely to jeopardize public safety” if released.

The department’s legal counsel suggested that disclosure of the documents “would not be in the public interest and would prejudice the possibility of effective law enforcement.”

“More specifically,” reads the February 13 rejection letter, “the protection of such investigatory materials and reports is essential to ensure that the Department can continue to effectively monitor and control criminal activity and thus protect the safety of private citizens.”

Notably, BPD issued identical rejection letters to two of MuckRock’s requests for StingRay documents. The first rejection was in response to a request for StingRay acquisition and policy documents, and was emailed to MuckRock on the same day the department responded to Katz-Lacabe.

On March 5, the department also rejected a followup request for communications with the FBI regarding public records requests for StingRay. Again, both outright rejections are the same as the one embedded above, word for word.

The department has yet to issue a final response for MuckRock’s third request for a range of StingRay documents, which was submitted in early April.

Katz-Lacabe appealed BPD’s refusal to release documents to the Massachusetts Supervisor of Records. In his March letter to the state, he argued that the invoked exemptions do not apply, and that disclosure of StingRay documents is in the public interest.

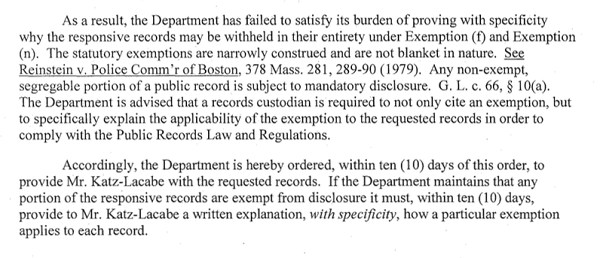

The state determined last week that BPD’s template rejection language does not make a sufficient case for withholding StingRay documents.

The May 13 order notes that BPD’s response “does not explain how these requested records pertain to an ongoing investigation, confidential investigative techniques, or witness statements,” and likewise “fails to demonstrate how disclosure of these particular records would prejudice investigative efforts as required by Exemption (f).”

“With regard to Exemption (n),” the letter reads, “this response merely cites the exemption and does not address the security-related rationale needed to justify withholding records under this exemption.”

The Supervisor also cited case law that qualifies exemptions under the state public records statute as narrowly construed rather than “blanket in nature.”

In light of the department’s vagueries, the Supervisor ordered Boston police to release StingRay documents within ten days, or else provide “a written explanation, with specificity, how a particular exemption applies to each record” [emphasis theirs].

A spokesperson for Boston Police Department replied today that he was unsure whether the agency has received a copy of the state’s order. We will update as to BPD’s release of documents regarding cell phone tracking equipment, or the department’s specific reasoning for keeping them from public inspection.