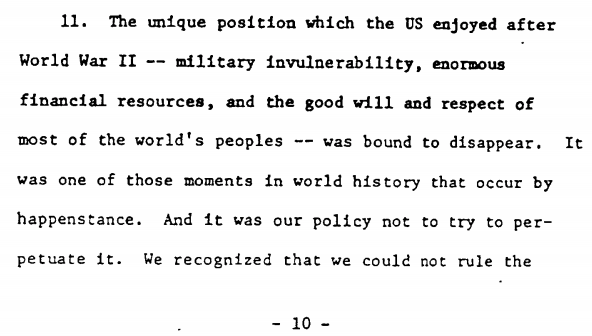

The Central Intelligence Agency’s “The World Situation in 1970” report was a strange mixture of realistic concerns, candid admissions, and forced optimism. Early in the report, the CIA outright stated that it had been inevitable that the U.S. would lose “the good will and respect of most of the world’s peoples,” while also declaring it had been their policy to not true to perpetuate their good state of affairs after World War II.

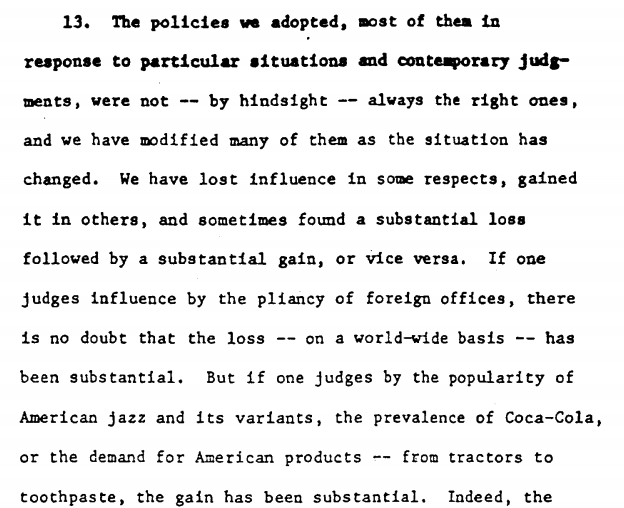

However, the Agency noted that in some instances this was not the result of a deliberate policy, but of “missteps.” Here, again, the CIA stressed perspective - while it was true that there had been a “substantial loss” of U.S. influence if one looked at how the U.S., well … influenced foreign offices and powers, this was not the only way to look at the world. “If one judges [American influence] by the popularity of American jazz … [or] the prevalence of Coca-Cola then “the gain has been substantial.” According to the Agency, the popularity for these cultural elements created dependence on the American and other Western systems that produced and supported them. While the CIA’s policies and programs might have been failures, all Americans were apparently winners if Coca-Cola sales went up.

Socialist consumption of Coca-Cola was also seen by the Agency as a secret sign that they were winning.

In other sections, the Agency showed signs of maturing. After 23 years of operating on an international scale, CIA realized that categorizing entire nations as “good guys” and “bad guys” was both impractical and inaccurate.

Decades before the internet became a household thing, the Agency predicted that changes in technology, especially relating to communications, was causing individuals “to believe that they have rights as persons they did not know they possessed or had reason to think could be realized.”

In one of its more actionable sections, the CIA assessed that the Soviet Union have had “an insoluble problem” in Eastern Europe due to economic and political threats and a failure to cooperate.

In spite of this apparent failure to fully cooperate, the Agency reported “a shift in Soviet thinking toward the view that perhaps with more rational Americans it might be possible to arrange some sort of stabilization in Europe” and other areas.

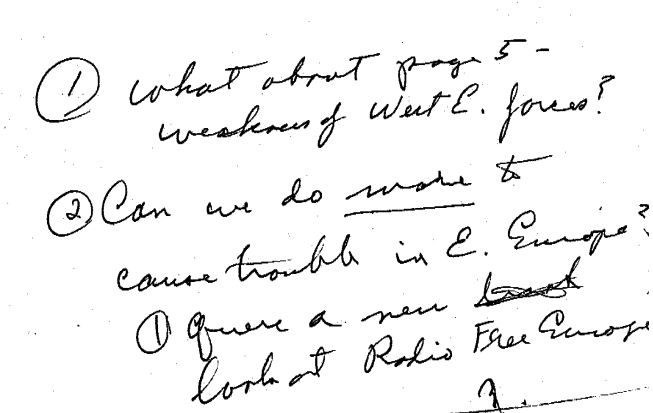

The report was sent from National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger’s office to the Oval Office. In response to the report, President Richard Nixon sent back several “Presidential comments.” The second of these comments asked “Can we do more to cause trouble in E. Europe?” As a sub-comment, the President suggested “a new look at Radio Free Europe.”

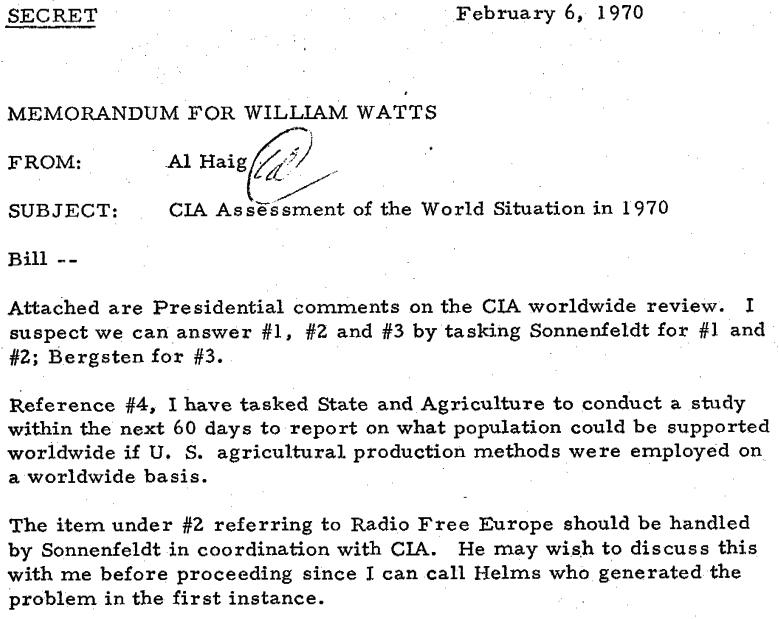

White House Chief of Staff Alexander Haig responded with a classified memo by suggesting individuals to assign the different asks and queries to. Haig also proposed calling CIA Director Richard Helms, who had apparently “generated the problem in the first instance.”

Nixon’s suggestion to use Radio Free Europe not merely to reinforce American ideas or spread what the U.S. government labeled as objective information, but to “cause more trouble” will likely reinforce certain conspiracy theories, though it’s unclear if the possibility went beyond Nixonian ponderings. In fact, all the details of how the comments were followed up on, or what this resulted in, remains as unknown as how Helms “generated the problem,” so MuckRock has filed a new FOIA request to learn more.

In the meantime, you can read the full report embedded below or on the request page, and Haig and Nixon’s responses here.