On October 15th, 1981, then-Central Intelligence Agency Director William Casey traveled to Brown University’s campus in Providence, Rhode Island. Invited by CIA administrator turned Brown professor Lyman Kirkpatrick, Casey was to speak as part of the Olin Lecture Series, funded by ultra-conservative chemical and munitions baron John M. Olin in his quest to combat leftism at elite universities.

Campus activists united to plan a protest of Casey’s speech, wanting to draw attention to the CIA’s track record of overthrowing democratically-elected governments (among other things) and Olin’s role in supplying the US military. “We were tired of the everyday picket with signs,” explained Mark Toney, then an undergrad at Brown, saying the group wanted something special, “to show how absurd all the lies were from William Casey.”

What they came up with - and its aftermath - made national news. And, with the CIA zeroed in on its campus image, also left a trail of documents in the agency’s archives, declassified and available online as of last year.

On the night of Casey’s speech, hundred packed into Brown’s Alumnae Hall. Leaflets distributed that night by a group of professors against the lecture ended up in the hands of Brown political science Professor Newell Stultz, who introduced the CIA Director. Stultz warned against any disruption by would-be protestors, according to a transcript later provided to the CIA.

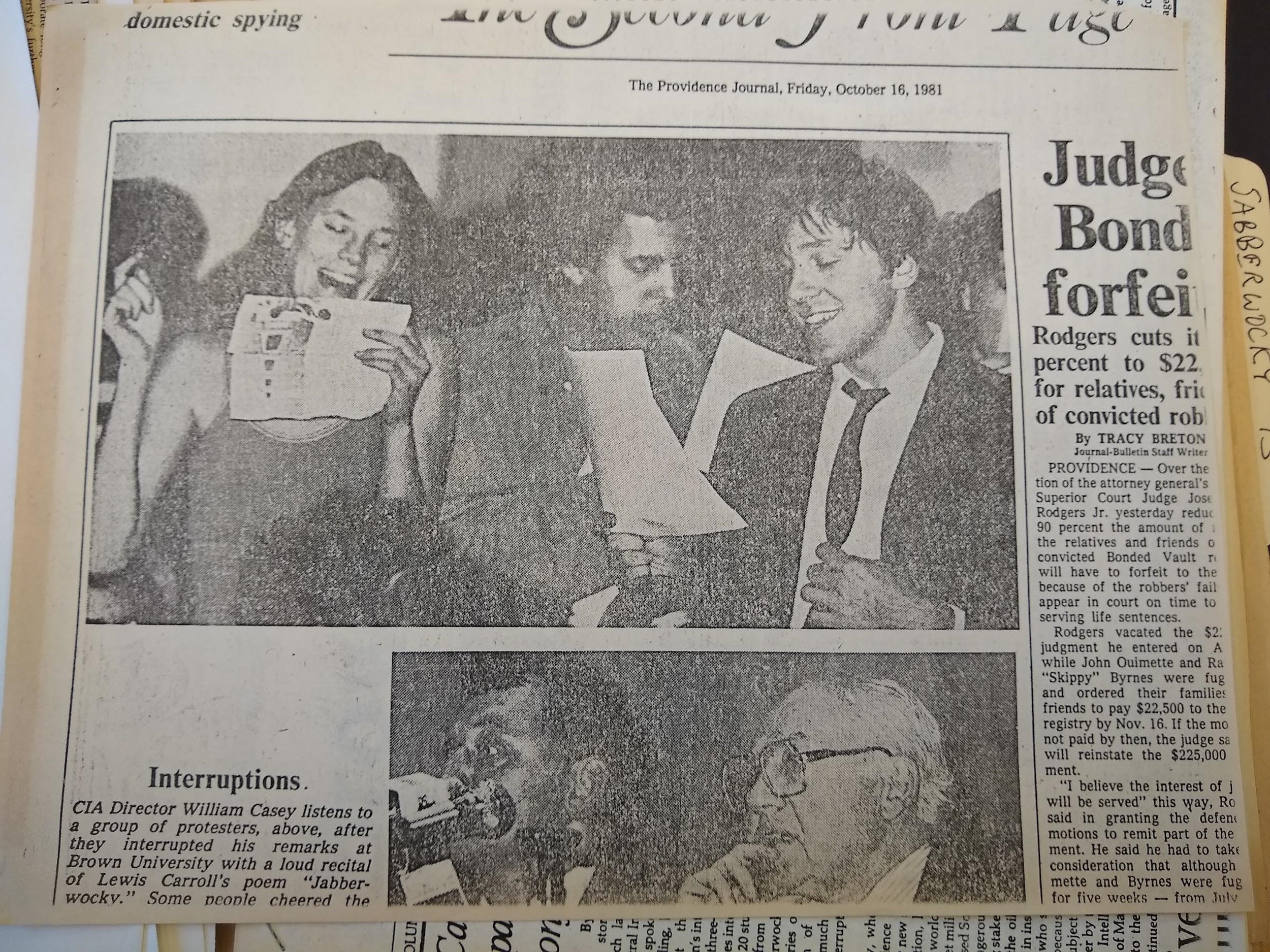

Casey began his lecture, titled “American Intelligence Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow.” Fifteen minutes into the speech, a member of the audience stood up and yelled “Jabberwocky!” - a cue for a group of students, including Toney, scattered throughout the room. The protestors produced copies of Lewis Carroll’s famous nonsense poem and recited it, loudly and in unison. Afterwards, they sat down, and after some booing and clapping, Casey carried on. The entire disruption lasted “some 3-5 minutes” according to a Brown University Police Department write-up of the incident. Toney remembers it as “a very low-key event” simply meant to “communicate absurdity.”

Some Brown administrators felt very differently. Brown University President Howard Swearer quickly sent an apology letter to Casey at the CIA. Several alumni and students followed suit, some even going so far as to lament the protest directly to President Ronald Reagan. Others axed their donations to their alma mater.

Words of apology and indignation were followed by disciplinary action. Five days after the lecture, Toney and several other students received a letter detailing misconduct charges from Dean of Students John Robinson, who had attended the event and identified a few of the student protestors.

“It wasn’t a big deal until the administration decided to make it a big deal,” said Toney. He began working on media strategy for the charged students and decided to brand the group as the “Jabberwocky 13.” “It wasn’t 13 people; it was probably 17 or 18, but I thought 13 sounded better and would catch people’s attention,” he said.

Toney was right. As he worked at Brown’s print shop, he had access to stationary with university letterhead, which the Jabberwocky protestors used to send press releases to national newspapers. “It’s part of why our mail got opened by journalists,” he said, “it came on the official embossed Brown stationary.”

The protest and disciplinary proceedings were picked up by the New York Times and the Associated Press (and the CIA).

On campus, the Jabberwocky 13 prepared for a disciplinary hearing before the University Council on Student Affairs, which took place on November 6th, 1981 before an audience of hundreds of students and faculty.

Their defense strategy involved playing a recording of the protest that included Casey finishing his speech, to prove that the CIA Director’s free speech rights had not been meaningfully abridged. The group also criticized President Swearer and other university administrators for condemning the protest publicly before the disciplinary process had run its course.

Then, in a hilarious turn, the students called for testimony from their landlady, Mary Struck, who had been questioned by Brown Police Department Coordinator Glen Normile after the protest. “He came on like the Gestapo trying to track down those kids,” Struck told the Brown Daily Herald. Normile told Struck that the students “could be part of what could be considered a radical organization,” according to the Herald.

The UCSA found the Jabberwocky 13 guilty of “infringement of the rights of others,” but doled out no punishment. “We considered that an enormous victory,” said Toney, who went on to found Direct Action for Rights and Equality in Providence and now directs the Utility Reform Network in the San Francisco Bay Area.

The CIA kept record of the hearing and its results. When asked how he felt learning that he appeared in the archive, Toney replied, “I’m flattered. What do you expect - that’s their job,” adding, “this is not surprising.”

Casey’s visit may have made more of an impression on two young campus conservatives, who wrote to the CIA director requesting that he serve on the board of advisors for a fledgling campus publication (he politely declined, citing his position as a public official).

Their letter, and other documents publicly available in the CREST database, show a CIA keeping close tabs on universities across the nation. Explore those records, as well as others regarding the Agency’s activities on campus, via the link below.

Image by thurdl01 via Flickr and is licensed under CC BY 2.0