In 1975, Senator William Proxmire, drawing from a General Accountability Office (GAO) report about their difficulties getting agencies to cooperate, introduced legislation which would effectively force the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to allow itself to be audited by the GAO. In response, CIA began compiling materials to argue against it - an argument which was described by the Agency lawyer drafting it as “B.S.”

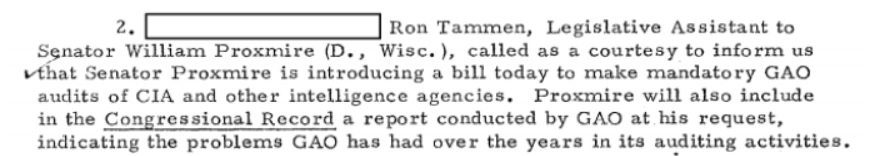

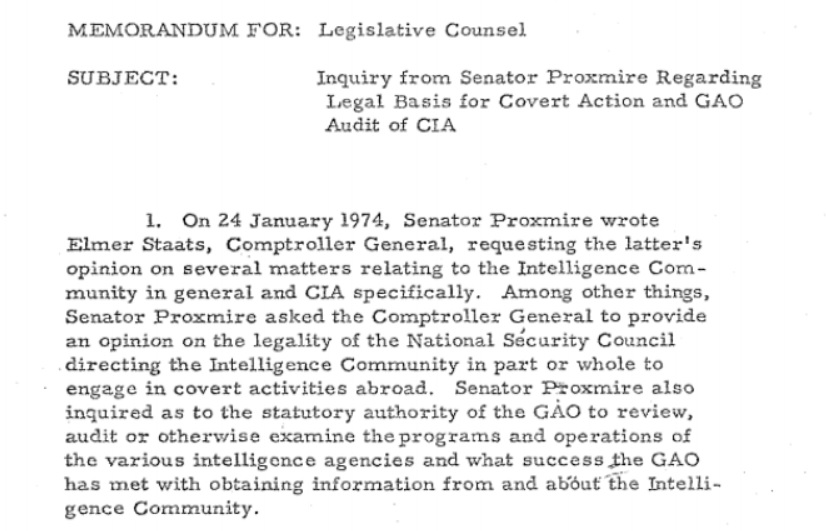

In addition to Proxmire’s reliance on a GAO report, the Senator had previously inquired about the Agency’s legal basis for various covert action, as well as the circumstances that led to the Agency’s policy against GAO audit. In response to this inquiry, made nearly a year before the Senator introduced legislation on the matter, CIA compiled a number of documents on CIA’s history with GAO and how the policy had come to be formed. As previously discussed, several of the letters in this packet were improperly withheld on the fraudulent basis of protecting sources and methods as confirmed by unredacted copies of the letters.

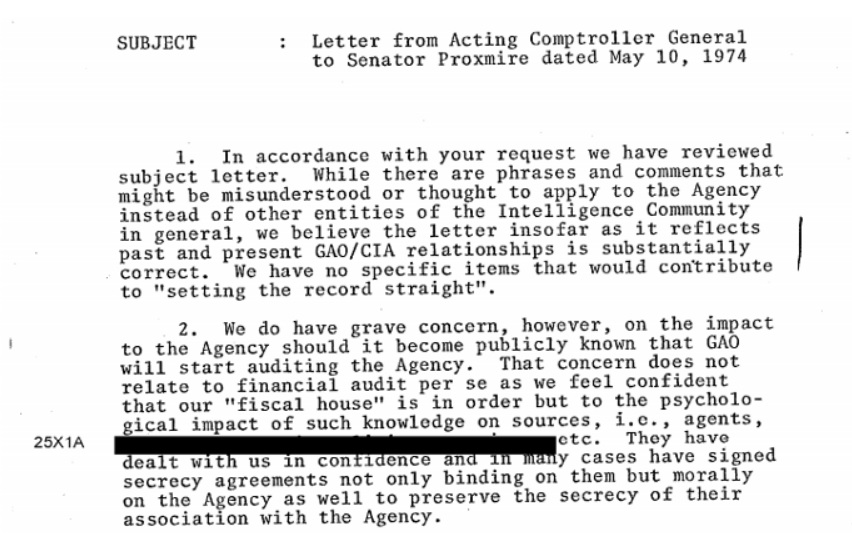

While the Senator had taken their time preparing the legislation and becoming well informed on the subject, CIA’s leadership quickly began scrambling to oppose it on a number of contradictory grounds. Shortly after the legislation was introduced, CIA Director of Finance Thomas Yale wrote a letter stating that they did not seek to “set the record straight” regarding a May 10, 1974 letter to Proxmire about the matter, or even to argue that there were any financial reasons to keep prevent the GAO from auditing the Agency. Instead, the Director of Finance argued that auditing the agency might have a psychological impact on CIA personnel.

The Director of Finance believed that the security risk, whether actual or mere perception, would have a negative impact on the Agency and discourage cooperation. Similar arguments are constantly raised by CIA against the Freedom of Information Act and virtually all other tools of oversight. The Director of Finance also wondered how they could assure “sources protection if outsiders are authorized to become privy to their names and intelligence, material or support provided?”

Such a question seemed to have been answered shortly before, however. According to Charles Kane, CIA’s Director of Security, “while there may [have been] just security policy reasons to limit the number of GAO personnel authorized access to intelligence material, any inference that the mechanics of security clearance processing is a hindrance to the GAO auditing procedures is incorrect.” Judging by the Director of Security’s letter, any perception that GAO would be given excessive or uncontrolled access to information was incorrect and should have been easy to correct.

The Director of Security went on to state that GAO auditors had apparently already been given access to the National Security Agency, and that such a clearance would be enough for CIA to grant them a temporary clearance at their Agency pending additional review. For other auditors, the Director of Security estimated that they could respond to clearance requests within 30 days, and that additional reviews would likely not require more than a few days time.

Nearly two months later, the same Director of Security would argue that their security clearances were not enough to keep the Agency safe from government auditors. No details were provided in support of the Director of Security’s statement, except that he agreed with letter that had been drafted by CIA’s lawyers and that he “did not believe it is a sufficient defense of our foreign and domestic assets to simply require a security clearance of the General Accounting Office personnel assigned to audit intelligence agencies.”

Instead, the Director of Security suggested that “a designated group of GAO officers” would be selected. These GAO officers would fulfill “all security requirements of CIA staff employees,” essentially requiring the detailed security checks clearances the Director of Security felt would be insufficient. These GAO officers would be taken on “prescribed tours with the sole purpose of attending to GAO audit requirements of CIA programs.” According to the Director of Security, this would be an “expanded” version of the Agency’s previous relationship with the GAO. It also would have kept CIA in complete control of what the GAO auditors looked at.

Read Part 2 here

Like Emma Best’s work? Support her on Patreon.

Image via CIA Flickr