It has been two months since Reuters reported on discussions inside the Trump administration to rebrand the national Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) strategy to focus exclusively and explicitly on Muslims. Since then the administration has maintained complete silence on the strategy even as local and state agencies have continued to develop their own initiatives, many of which were promised significant funding under the last days of the Obama administration.

One of the initiatives awarded a $300 thousand grant by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) under the Obama administration belonged to the Nebraska Emergency Management Agency (NEMA). While it is unclear whether these funds have been disbursed, the initiative seems to nonetheless be proceeding, at least according to a report from a local news agency in Nebraska.

NEMA’s grant proposal, acquired through a Nebraska Public Records Statutes request, is similar to Boston’s public health approach to CVE and claims to follow the Montgomery County model, calling the latter “successful” even though its success is more public relations than reality.

According to NEMA’s proposal, the major CVE-related needs in the state are “barriers to reporting warning signs of radicalization.” and the “expertise to assess threats.”

The state’s plan is to address the barriers faced by peers, family members, and other bystanders in reporting “behaviors of concern” to public health departments and trusted organizations by establishing good relationships with communities through “transparency and good communication.”

State agencies involved in the initiative would “disseminate existing material about radicalization and extremism,” “gather perceptions about barriers,” and “develop [an] evidence based approach to facilitate reporting.” This would lead to “increased engagement of community,” an “increased knowledge of CVE warning signs,” and an “increased trust of [the] reporting process.”

State agencies will also insinuate CVE approaches into public health institutions and schools to engage the community, youth, and families.

The “expertise” is to be provided by the University of Nebraska Public Policy Center and the Nebraska State Patrol’s Fusion Center, which “has considerable expertise in CVE and is the state’s primary agency for analyzing threats.”

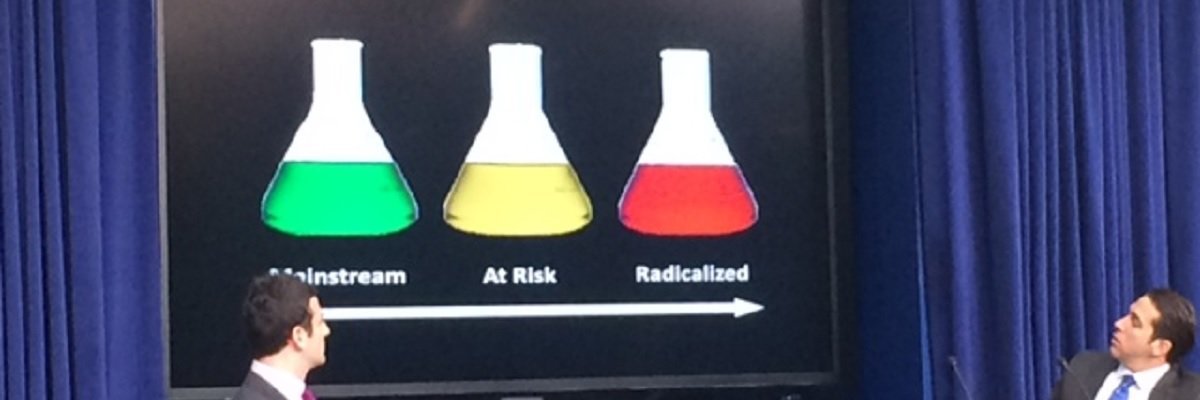

Like other CVE initiatives, NEMA’s proposal is also riddled with inconsistencies and contradictions. It somehow maintains that that there are “observable behaviors that seem to be associated with the process of radicalization” while conceding that “violence may occur in the absence of extreme ideology, and radicalization may not always result in violence.” It goes on to advocate the creation of “checklists or structured professional judgement tools to aid in screening individuals who may be vulnerable to radicalization” while conceding that “there is no ‘profile’ of someone who is likely to be a violent extremist.”

The use of “checklists or structured professional judgement tools” has long been discredited by numerous studies. As former CIA official Marc Sageman has demonstrated, even a tool with 99% specificity would have less than 1% probability that it would identify a person actually susceptible to violent extremism. This is because for every hundred evaluations, the tool would make one error. If there were 100 individuals vulnerable to violent extremism in a population of one million, the tool would falsely identify 10,000 people as potential terrorists.

That this would be the case with a tool with 99% accuracy leaves no doubt that Nebraska’s CVE model would do little other than produce false positives.

Not surprisingly, the proposal does not identify the factors which may be included in a checklist other than to say that “violent extremists preparing to martyr themselves are careful to pay off debts prior to attack rather than racking up debt.” There are no indications that this novel insight was ever compared to a control group of individuals who repay their debts and do not carry out attacks.

Implementing CVE approaches in public health institutions and schools has its own set of problems. As a growing body of evidence indicates, such approaches destroy the necessary trust between teachers and students and between medical and mental health professionals and patients. Moreover, as a report by the Open Society Justice Initiative on the impact of Britain’s counter-terror strategy in public health and educational facilities concluded, the strategy posed “a serious risk of human rights violations.”

There is little acknowledgement of the risks of the public health approach adopted by Nebraska. In this it does not differ from CVE initiatives across the country which take few, if any, measures to protect the civil liberties of their targets or to ensure that targeted communities are not stigmatized. Indeed, the wholesale adoption of approaches based on premises that have long been debunked, with a near certainty that they will be ineffective, and which entail significant civil liberties risk only goes to show that these factors are central to CVE and will remain so - regardless of whether the Trump administration rebrands the strategy.

Read the full proposal embedded below, or on the request page.

Image via MuslimAdvocates.org