Read Part One here.

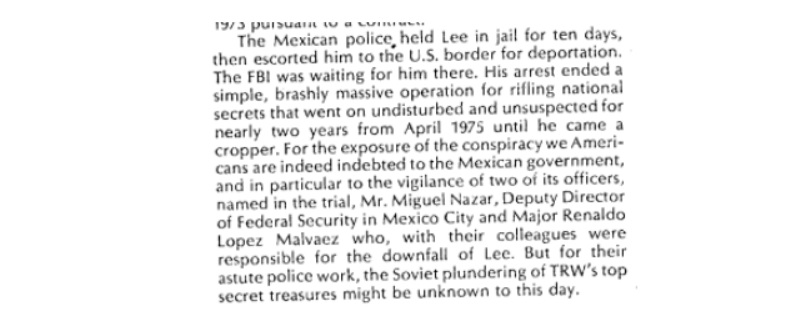

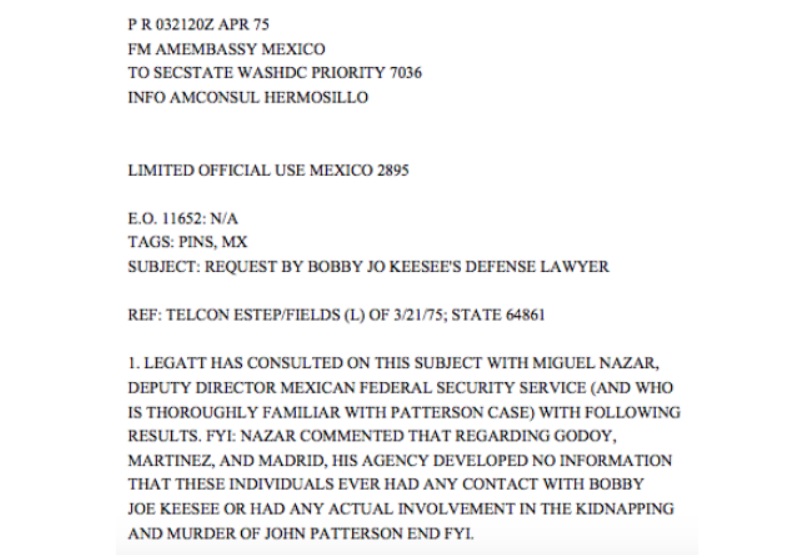

According to a common and largely sanitized version of events regarding Christopher John Boyce and Andrew Daulton Lee, respectively known in popular culture as “the falcon” and “the snowman,” Miguel Nazar Haro, as head of the Direccion Federal de Seguridad (DFS), was one of two Mexican policemen largely responsible for the U.S.’s capture and prosecution of Lee, which led to the capture of Boyce as well.

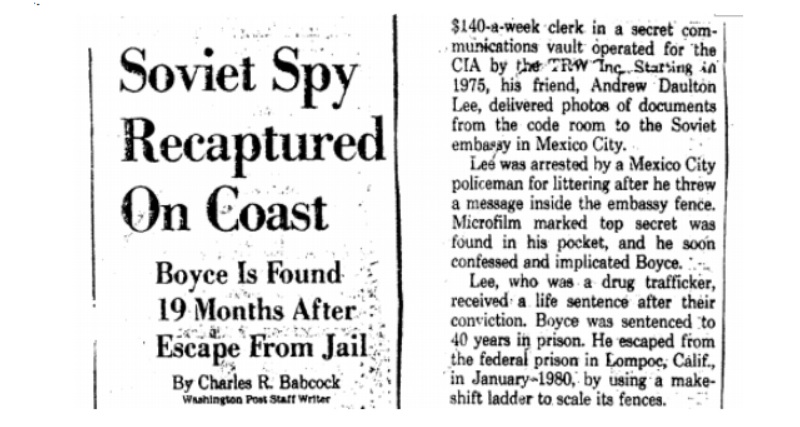

This version of events is similar to the one the court describes, in which “Lee was arrested by Mexican authorities in front of the Russian Embassy in Mexico City, Mexico, when he stuck his head through the Embassy fence and discarded some “trash” from his pockets. Lee was taken to Mexican police headquarters for questioning. When asked to empty his pockets, Lee removed a white four-inch by eight-inch business envelope which contained ten to fifteen strips of photographic film negatives.” The Washington Post similarly reported that “Lee was arrested by a Mexico City policeman for littering after he threw a message inside the embassy fence. Microfilm marked top secret was found in his pocket, and he soon confessed and implicated Boyce.”

While none of that is false, it leaves out such a large amount of significant information that the narrative presented isn’t accurate. The New York Times’ account, for instance, mentions that Lee tried to bribe the Mexican police into releasing him, but fails to mention that this was immediately after they falsely (and baselessly) accused him of terrorism. It also leaves out the fact that Lee was tortured by the Mexican authorities prior to confessing and signing the FBI’s Miranda waiver.

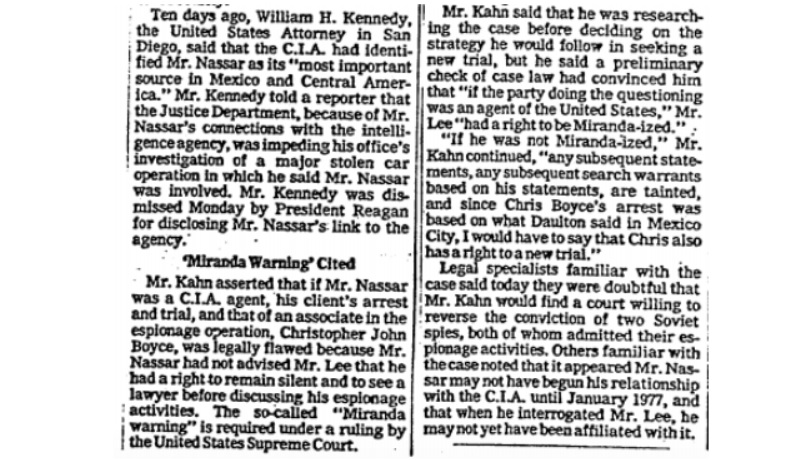

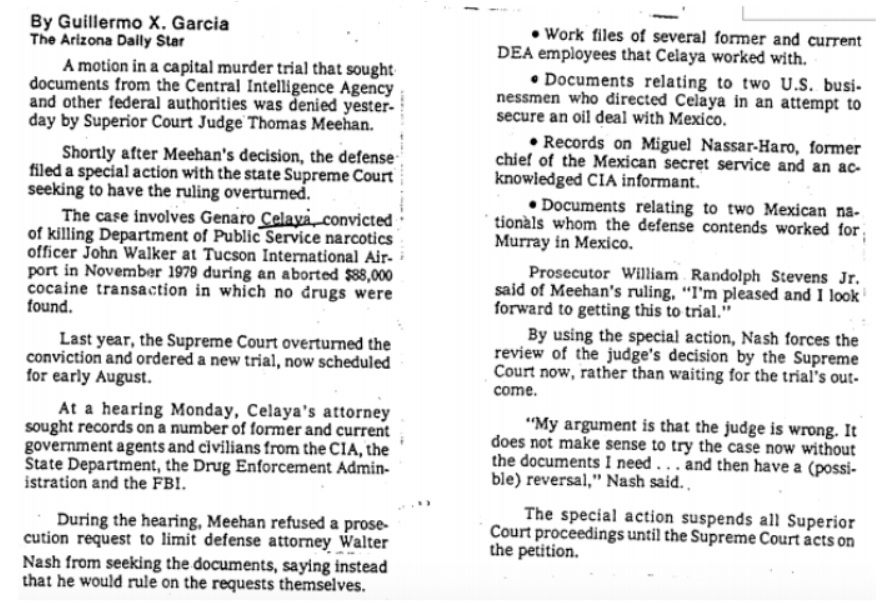

Nazar’s involvement with the case, as well as the way it was handled in Mexico, created unique legal challenges - especially in light of the revelation that Nazar was a Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) asset. This specifically raised new legal challenges that Lee’s lawyer wanted to explore in court. According to Kahn, Lee’s lawyer, “if the party doing the questioning was an agent of the United States,” as it appeared that Nazar was, “[then Lee] had a right to be Miranda-ized. If he wasn’t Miranda-ized, any subsequent statements, any subsequent search warrants based on his statements, are tainted, and since Chris Boyce’s arrest was based on what Daulton said in Mexico City, I would have to say that Chris also has a right to a new trial.”

While some legal specialists had their doubts about a court being willing to reverse the conviction on this basis, the legal question itself appears to have been a valid one. One legal expert, Mark Zaid, recently expressed doubt that it would have worked, but acknowledged that it would have created an additional potential for Nazar to use graymail. Previous decisions, such as 1957’s Reid v. Covert, had found that “the Constitution imposes substantive constraints on the Federal Government, even when it operates abroad.” This makes the question of Nazar’s status all the more relevant.

The additional explanation offered in the excerpt above, that Nazar “may not have begun his relationship with the C.I.A. until January 1977, and that when he interrogated Mr. Lee, he may not yet have been affiliated with it”, is simply and clearly false. Nazar’s relationship with the Agency began more than a decade earlier, as indicated by declassified documents and supported by interviews conducted by Jefferson Morley and others. Even if there was any lingering doubt remaining about Nazar having been assigned the CIA cryptonym LITEMPO-12 (an Agency document identifies a letter signed by Nazar as having been sent to the Agency by LITEMPO-12, all but confirming that it was Nazar), there is no doubt that he was liaising with the federal government years earlier, as shown by declassified diplomatic cables.

The secrecy around the trial might also have aided an attempt to raise the issue anew in court, which Nazar could have easily exploited by offering to provide testimony to help Lee as part of an effort to put pressure on the Agency. According to the New York Times, “The C.I.A., which originally resisted prosecuting the youths because it feared defense secrets would be revealed, severely limited what information it would release to the court, and Federal Judge Robert Kelleher usually upheld Government objections when testimony began to stray into areas of national defense.” Kahn could have easily combined this with other challenges he brought before the court, such as that the Judge was shown ‘thousands of top secret documents never shown to the defense.’

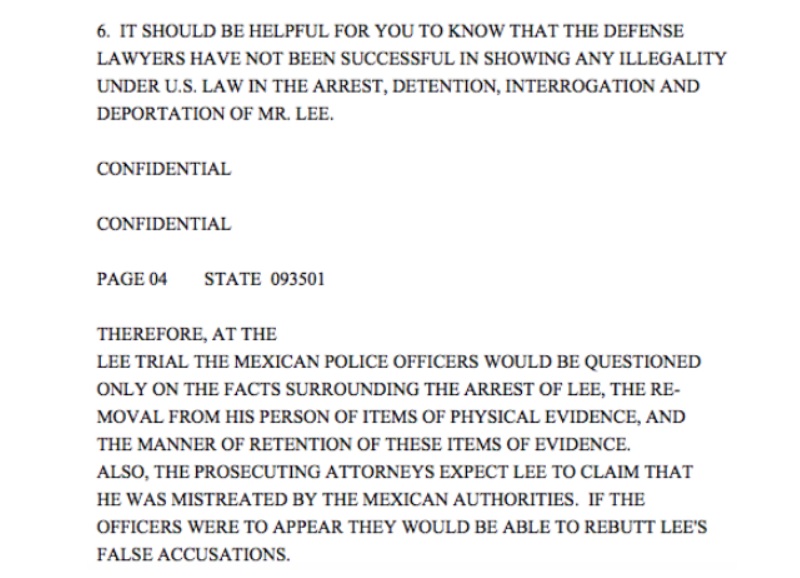

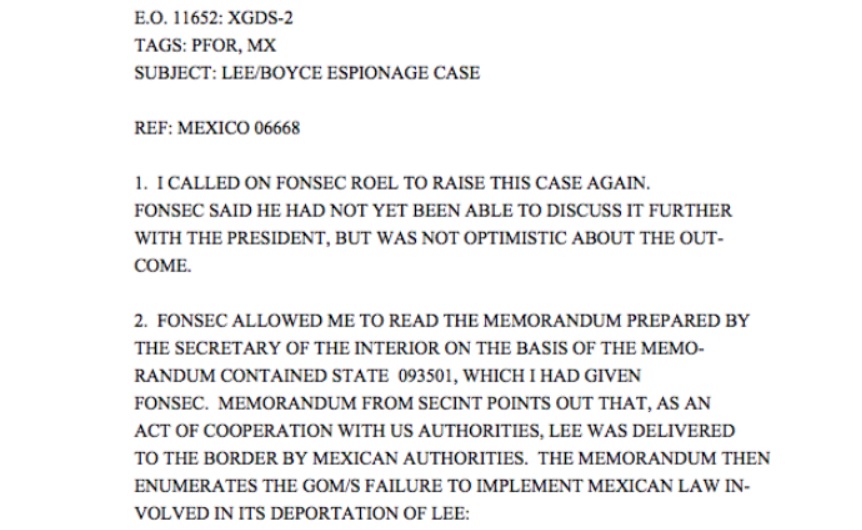

If Kahn had been able to put Nazar front and center in the Lee case, it likely would’ve raised other issues that the U.S. Government and Lee’s prosecutors had been worried about years before, such as the need to have the Mexican officers testify at Lee’s trial or the circumstances around his “deportation.” One diplomatic cable sent by the U.S. Secretary of State, attempting to help convince Mexico’s Foreign Ministry to have the officers to come to the U.S. to testify in Lee’s trial, that Lee’s attorney had “not been successful in showing any illegality under U.S. law in the arrest, detention, interrogation and deportation of Mr. Lee.”

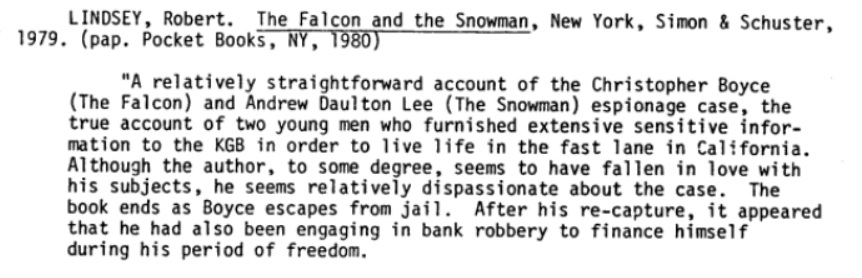

The prosecutor, however, expected Lee to claim to that he was “mistreated” by the Mexican authorities. The U.S. wanted these claims to be refuted, though this might not have been possible without delving into falsehoods. According to multiple accounts, Lee was tortured and threatened with genital mutilation. These accounts include The Falcon and the Snowman, which the DIA’s Defense Intelligence School (now the National Intelligence University) described as “a relatively straightforward account” and “the true account” of the the Boyce-Lee spy ring. However, the book’s account remains largely uncontested, with some of the participants in the book’s events confirming its accuracy and several detailed accounts agreeing that the torture took place. Mexico’s own Special Prosecutor even noted the history of Nazar and his organization engaging in torture.

In response to the Secretary of State’s declaration that Lee’s defense attorney hadn’t been able to show any illegalities under U.S. law regarding his deportation, Mexico’s Secretary of Foreign Affairs shared a memo prepared by their Secretary of the Interior, outlining some of the problems with the case - problems that Nazar would‘ve been more than able to exploit in either a graymail or blackmail attempt against the governments of the United States and Mexico.

First, Lee was arrested in Mexico with marijuana in his possession after having entered Mexico illegally. In spite of this fact and his incarceration in Mexico, “no formal investigation was conducted … nor were any charges brought against him as required by Mexican law.” These would not be the only irregularities in the handling of Lee’s case. The accounts of what prompted his arrest and and what he was accused of by Mexican police all vary slightly, with different versions citing littering and others the suspicion of terrorism. Once Lee had been arrested, however, Mexican authorities informed him that he was suspected of having killed a policeman. The “evidence” for this was that Lee had a postcard of a landmark where a police officer had been previous killed.

A second and potentially more serious exception to standard procedure was raised in the memo regarding how Lee came to be delivered into U.S. hands. While Lee was delivered to the U.S.-Mexico border “as an act of cooperation with U.S. authorities … this was not accomplished through an extradition process.” The memo offered by Mexico’s Attorney General reportedly offered similar conclusions.

The American Ambassador in Mexico pointed out that “Lee had not been delivered to the border at [America’s] request.” While this may be true, former FBI Special Agent John Foarde described Lee’s trip up to the border as taking the Bureau by surprise, though he also admits that they knew about it before it happened and didn’t want to stop it. Several other FBI Agents who worked on the case also confirmed foreknowledge of Lee’s “deportation.” While the issue had been dealt with at pre-trial, Lee’s lawyers were not aware at the time that Nazar was a CIA asset working for the U.S. Government in addition to his role in DFS. This by itself raised new potential challenges, challenges which would have been greatly aided had Nazar decided to help Lee’s lawyer. The diplomatic cable makes it clear that Nazar’s ability to use graymail and blackmail wasn’t limited to the U.S. Government, as the way the affair was handled was potentially damaging to the Government of Mexico.

The question of CIA’s involvement in the case extends beyond the simple existence of their pre-existing relationship with Nazar. According to Foarde, the Agency was aware of the arrest of Lee before the Bureau’s legat office in Mexico City was informed of it. In Foarde’s account, a woman from the U.S. Embassy was leaving the Soviet Embassy at the time of Lee’s arrest. The Falcon and the Snowman identifies this woman as Eileen Heaphy, who declined to comment except to say that the book was accurate. Foarde explained that as a result of Ms. Heaphy’s report to the consulate, “the word got around pretty quickly to that agency that we normally don’t mention very loudly. And so we weren’t even aware of it in our office until, I think, the next day. I think we got a call from the Bureau that this had happened, and so then we got busy with it.”

According to the book and the statements by Foarde, after Lee’s torture at the hands of DFS, the FBI paid him a visit. During this visit he signed a waiver against his miranda rights, largely confessed and identified his partner in crime, Christopher Boyce. As pressure around the case began to build up, the Mexican government didn’t want to admit they had Lee in their possession. Instead, they drove him to the border and told him they were deporting him. The Bureau arrived shortly before Lee was sent across the border, with FBI Special Agent Robert Lyons getting a signed confession from Lee. In addition to having been tortured, one FBI agent suggest that Lee may have suffered diminished capacity at the time. According to former FBI Special Agent Richard Ault, during this period Lee had been “so doped up” that he was going through withdrawal. As a result, “he couldn’t remember most of what he’d done in Mexico City.”

As Lee crossed the border after having been told he was being deported, he was arrested by the FBI. As Mexican officials had noted, this wasn’t done through the extradition process nor was Lee either investigated for or charged with illegally being in the country, a fact which raises additional questions about the deportation process.

According to the interview with Foarde, Nazar was handling the Lee case for Mexico at the time, going so far as to keep Lee locked up near his office.

Foarde added that the FBI “couldn’t do much to stop” Mexico from sending Lee across the border in the way they did. “Nor would we want to,” he added, adding to the doubt about how Lee was sent across the border.

The claim that the graymail concerns had been successfully addressed is further undermined by the government’s disinclination to turn over documents about Nazar’s CIA relationship in a 1984 case that went to the Supreme Court several years later.

Even accepting the Agency’s statements that their only concern was over graymail, and that they had managed to set aside those concerns by the time Nazar was arrested, it neither explains nor excuses CIA’s failure to be prepared for this situation. The Agency, for its part, was well aware of both Nazar’s and DFS’ reputation. Nazar was well known in Mexico as a brutal individual, more capable of having people disappeared or tortured and DFS’ corruption was virtually infamous. CIA knew about DFS’ and Nazar’s activities better than most: since the early ’60s, the Agency had been listening to DFS’ phone calls.

The Agency’s intelligence led it to conclude that the DFS was “largely poorly trained, insecure and unreliable. Their professional characteristics are best described as being dishonest, cruel, and abusive.” While this assessment was given in the early 1960s, neither DFS’ behavior nor its reputation would improve over the next thirty years. Under CIA’s and Nazar’s watchful eye, the cruelty, abuse and corruption of DFS would seem to only increase until its dissolution in the mid-1980s. In the late 1980s, one police source described to the Los Angeles Times how the pattern of corruption grew, saying that DFS “controlled the state police, and the Federal Judicial Police was subservient to them. They came from the most powerful institution outside of the presidency - the Interior Ministry. Maybe they were asked to do things they were later owed a favor for. The organization gained strength under Nazar Haro, and he continued to have a very close relationship with these people. It’s a fraternity.”

A declassified diplomatic cable from the early ’90s confirms that the defunct DFS’ reputation remained unchanged, calling it “an agency with a reputation for corruption and ruthlessness.” Until 2003, this determination and description of the agency was considered classified by the U.S. Government, based on the previous redaction and the exemption marking.

CIA’s willingness to tolerate this corruption and brutality may be explained by their previously SECRET analysis from 1985, which states that some believe that “corruption in general is essential to the operation and survival of Mexico’s complex form of government.” The mere attempt to make “abrupt, lasting changes to this structure, for whatever purpose, would disturb the balance of political alliances that has ensured stability for six decades.” The period of “stability” CIA describes includes Mexico’s “Dirty War,” which saw at least 1,200 dissidents and other individuals being “disappeared.”

The “Dirty War,” nestled in the middle of what the Agency called a period of “stability” for the country was carried out in part by Naza and the DFS. Nazar would later be arrested for his role in the “disappearance” of 1,200 dissidents, and investigated for torture, murder, and even genocide, all while working with, and protected by, the CIA.

The issue of Nazar’s ability to use graymail or blackmail against the U.S. Government goes beyond his official contacts and liaisons in ways that are impossible for anyone, inside or outside the U.S. Government, to fully evaluate. As reported by Morley’s Our Man in Mexico, Win Scott retired from his position as CIA Station Chief in Mexico City, opening his own company along with retired British intelligence office Fergie Dempster and former CIA Station Chief in London, Al Ulmer. Known as DiCoSe, short for Diversified Corporate Services, the company was described by former Ambassador to Mexico Thomas Mann as Win’s “own personal intelligence organization… [which the Mexicans] wanted to use.”

This arrangement would prove quite lucrative as Win worked with both individuals as well as the governments and militaries of both the United States and Mexico. By this point, Win had been working with Nazar for sometime and felt that he owed the senior DFS official a favor. As a result, Win hired Nazar’s daughter as a secretary despite his complaints that she couldn’t type. Evaluating what she might have learned from overhearing discussions fueled by one too many gin and tonics or by snooping around Scott’s papers would be impossible for the Agency. Even if Scott had practiced perfect security and never let anything slip, the Agency would be unable to determine that. Nor could the Agency preclude the possibility that her access and familiarity with the offices would’ve helped enable black bag entries by Nazar.

Other graymail opportunities that Nazar could have exploited remain further buried. One such connection was highlighted by a study produced by the Institute for Policy Studies, which was inserted into the Congressional Record for the Intelligence Authorization Act for FY 1999 in the alleged Agency involvement in a plot to overthrow the Portuguese government in the 1970s. “In 1974, Sicilia’s top aide, Jose Egozi, a CIA-trained intelligence officer and Bay of Pigs veteran, reportedly lined up agency support for a right-wing plot to overthrow the Portuguese government. Among the top Mexican politicians, law enforcement and intelligence officials from whom Sicilia enjoyed support was Miguel Nazar Haro, head of the Direccion Federal de Seguridad (DFS), who the CIA admits was its `most important source in Mexico and Central America.’ When Nazar was linked to a multi-million-dollar stolen car ring several years later, the CIA intervenes to prevent his indictment in the United States.”

Even if one sets aside the statements from multiple witnesses that the Agency tried to block the case because of Nazar’s value to them, and even if accepts the graymail explanation, it still doesn’t adequately explain the Agency’s behavior. They allowed themselves to be put into a position where the threat of graymail and blackmail were both real. The Agency was well aware of the DFS’ corruption and abuse, as well as the accusations made against Nazar. This alone created the potential for graymail and blackmail, as does the Agency’s tolerance for corruption and abuse in the name of maintaining stability. Nazar was also, as the head of a foreign intelligence service, a legitimate target of collection and counterintelligence by the Agency. Nazar’s involvement in the Snowman and the Falcon case as well as the investigations into Lee Harvey Oswald’s activities both created unique but utterly predictable situations for potential graymail and blackmail. The Agency has defended itself from charges of protecting Nazar by claiming prior incompetence in positive intelligence collection and basic counterintelligence activities.

More likely than incompetence, however, is that the Agency chose to turn a blind eye to these activities. As the Washington Post reported, “DEA and Mexican officials interviewed for this article said that at a minimum, the CIA had turned a blind eye to a burgeoning drug trade in cultivating its relationship with the DFS and pursuing what it regarded as other U.S. national security interests in Mexico and Central America.” According to retired DEA agent James Kuykendall, the Agency’s desire to protect the DFS to preserve their relationship meant that they shared some of the blame. As a result of the Agency’s protection, “the DFS just got out of hand.” According to witnesses in two different trials, Nazar was heavily involved in narcotics at the time that the Agency was trying to protect him.

One such witness, a former radio technician with the DFS named Victor Lorenzo Harrison, testified that Nazar had been involved in drug trafficking. The testimony also connected Nazar to Ernesto Fonseca Carrillo, one of the drug traffickers convicted in DEA Agent Kiki Camarena’s murder. The Guadalajara cartel, which had been responsible for the murder, was known to be protected by Nazar’s DFS. When Harrison tried to testify on these matters, the testimony was blocked by the judge. Harrison also told the DEA that Fonseca had met with an American drug smuggler who said they were “working with the contras.”

Both the government of Mexico and CIA acknowledged that the DFS had long protected the cartel and that it had, at a minimum, played a role in enabling the murder of Caramena, as noted by the same CIA report that suggested corruption in Mexico was desirable because it had “ensured stability for six decades.”

The DFS chief at the time of Caramena’s murder was José Antonio Zorrilla Pérez, an associate of Nazar’s. According to former policemen and intelligence officials, the corruption hadn’t improved under Zorilla. Eventually, Zorilla was directly implicated in both drug trafficking and a series of murders eliminating those who knew about it. These murders directly overlapped not only with Nazar’s web of corruption, but with his car theft ring.

In 1989, allegations rose that Raul Perez Carmona and Juventino Prado were among the individuals Zorrilla tapped when he commissioned the murder Mexican journalist Manuel Buendia, who was pursuing corruption stories that involved Zorrilla. Perez Carmona and Prado were two of the officials who were indicted as part of the Nazar car theft ring. Not long before the accusations were aired, Perez Carmona and Prado were chosen to replace Nazar in his latest intelligence post, which Nazar had been placed in by his old political ally Javier Garcia Paniagua, whose son had also been part of Nazar’s car theft ring. The son, Javier Garcia Morales, was later assassinated.

In his new post under Javier Garcia Paniagua, Nazar briefly served as the chief of the intelligence division of the Mexico City Police Department. According to a cable obtained by the National Security Archive, continued accusations against Nazar and his patron’s poor health both likely contributed to Nazar’s relatively swift retirement, after which he was replaced by Perez Carmona and Prado.

The FBI file on Nazar shows that similar conclusions were reached by the Bureau after they received a report from one of their sources. Others, however, speculated that Nazar’s stepping down may have been related to the pending certification hearing in the U.S. regarding Mexico’s compliance in the war on drugs. In connection with this, the Los Angeles Times cited “government witness in a San Diego trial of seven cocaine traffickers has testified that Nazar protected drug-smuggling operations and profited from the sale of confiscated narcotics while serving in the federal security agency.” This witness laid out a number of new and specific allegations against Nazar and his associates.

In 2012, Nazar’s story finally came to a close when he died. The efforts to rewrite it, however, hadn’t yet finished. According to Nazar’s son, for instance, he had refused to run from some of the later legal troubles he’d had during his lifetime, despite the advice from others. Nazar reportedly told his son, “I’ve never run from anything or anyone.”

The FBI and the U.S. Marshal’s Service might disagree.

The CIA report on Nazar’s stability is embedded below, and you read his FBI file on the request page.

Like Emma Best’s work? Support her on Patreon.

Image by Marcel·li Perelló via Wikimedia Commons