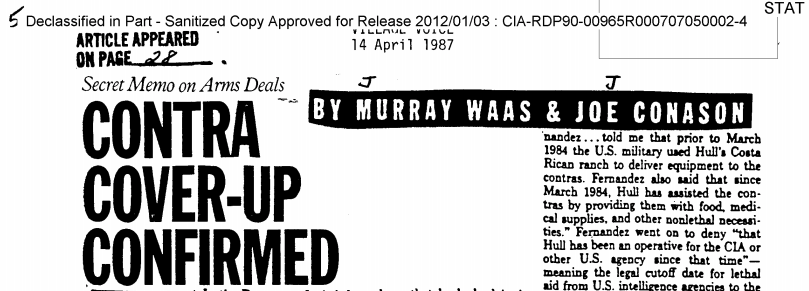

On April 14, 1987 the Village Voice once again made itself the target of a Federal Bureau of Investigation leak investigation when it published an article based on a leaked memo apparently confirming an Iran-Contra cover-up, amidst leaks and counter-leaks by whistleblowers and politically maneuvering Reagan Administration officials.

Although the memo itself wasn’t marked classified, a point that would become crucial later, it contained the names of two individuals doing covert work for the Central Intelligence Agency, John Hull and Joseph Fernandez. This was enough to trigger an investigation into the publication and its possible sources under the Intelligence Identities Protection Act. The Bureau’s investigation led to a senior official in the Department of Justice, one who had been a CIA officer and who was then under consideration for a senior position in the Department of Defense. The FBI closed the case on the mostly undocumented investigation, and the suspected leaker was put in charge of the military’s special operations. Immediately after 9/11, they returned to active duty to manage Unconventional Warfare operations in Afghanistan.

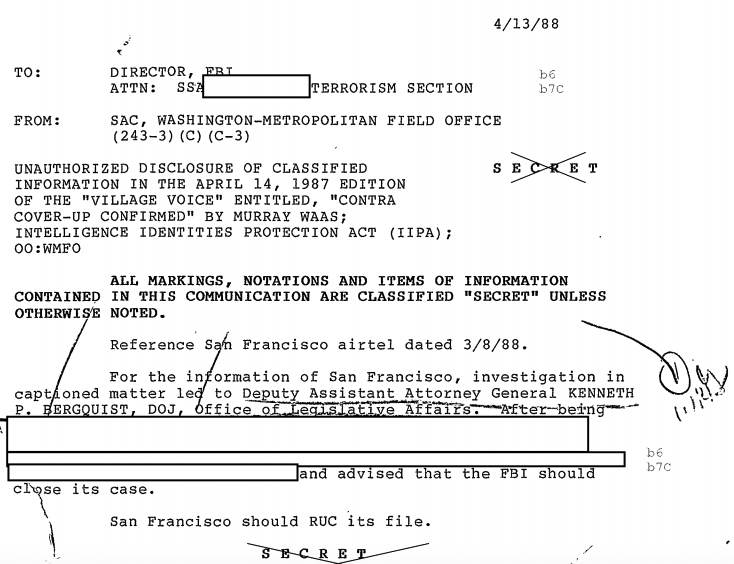

In most instances, the Bureau attempted to redact the name of Kenneth Bergquist, then the Deputy Assistant Attorney General (DAAG) for the Office of Legislative Affairs. In several notable instances, his name is partially or entirely visible. One notable memo to FBI Director William S. Sessions, originally classified SECRET, directly implicates the DAAG, stating outright that the investigation led to the DAAG. Once it did, something occurred which the Bureau redacted under “personal privacy” which resulted in the Bureau being instructed to “close its case.”

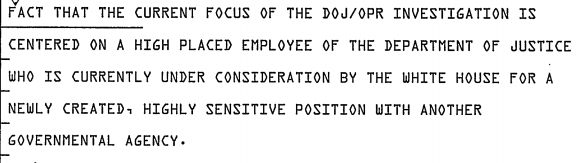

Any vagueness in the memo to the Director is dispelled by an earlier declassified memo from Acting Director John E. Otto. While the Director’s memo doesn’t name Bergquist, it does describe him rather precisely. According to the memo, the investigation was “centered on a high placed employee of the DOJ who is currently under consideration by the White House for a newly created, highly sensitive position with another government agency.” Several months before, President Reagan had nominated Berquist to take a newly created position within the Department of Defense, the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations/Low-Intensity Conflict (ASD(SO/LIC)). Bergquist was ultimately appointed as the Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Manpower and Reserve Affairs instead.

Another memo in the file itself states that the investigation focused on a DAAG describing Berquist with an additional layer of detail and going on to reference an article by author Murray Waas.

The person the FBI suspected of actually passing the memo to the press, however, appears to have been a Congressional staffer from the Senate Foreign Relations Subcommittee, who would have worked with and around Bergquist, the DAAG for OLA. One interview subject refused to discuss what they did with the memo, stating it fell under “Congressional privilege.” The FBI’s file reports that the individual “did not deny that his source was a DOJ employee,” saying instead that he considered them “to be the equivalent of a whistleblower.” The file also implies that the National Law Journal had said that the staffer received the memo from Administration sources. He added that the source told him the memo wasn’t classified and didn’t contain any national security information, apparently because the author “was not aware that he could classify a document.”

At several points, the file highlights the investigation’s unique nature. Although it was a criminal investigation, it was being handled by the Office of Professional Responsibility rather than the Criminal Division. There were also “no written reports of any interviews conducted” and “no written record of the DOJ/OPR investigation other than a pile of handwritten notes.”

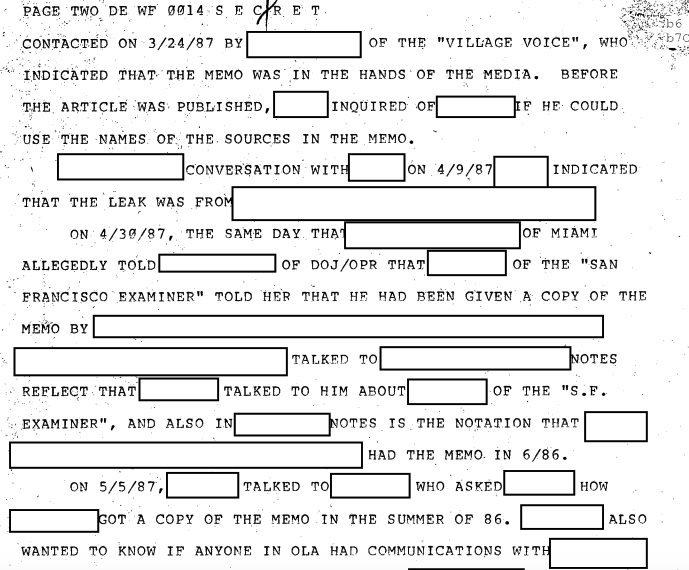

There were also multiple leaks of different versions of the memos, one in June 1986 and one the following year, the first apparently being a draft and the latter the final copy of the memo.

The June leak of the draft copy apparently occurred shortly before the OLA’s non-routine request for a copy of it.

A copy of the memo “was allegedly stolen from the unlocked files [redacted] probably sometime in the summer of 1986.”

Sometime in March or April the following year, shortly before the Village Voice’s article was published, some of the “original handwritten work product” the memo had been drawn from was slipped under his door, including the original handwritten footnote, of which the Village Voice had a copy.

The FBI had no shortage of theories to consider, though some were apparently discarded, such as one interviewee’s accusal of the Miami U.S. Attorney’s office.

The FBI were given a number of leads, including reported statements from the journalist’s involved about their sources’ identities. Throughout, the Bureau continued to look at the OLA.

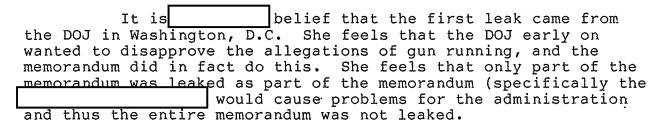

Another theory was that the first leak was to disprove accusations of government gun-running and that only part of the memo had leaked because the remainder “would cause problems for the administration.”

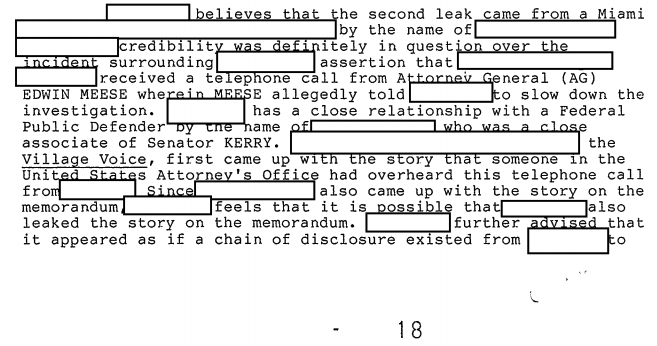

The same theory posited that the second leak had shared the first leak’s desire to protect the DOJ, specifically by discrediting accusations that Attorney General Meese was obstructing the investigation.

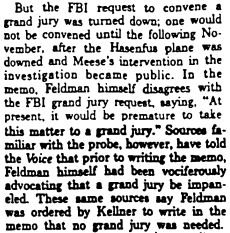

If the motivation was to disprove allegations that the DOJ was obstructing the investigation, then it is especially damning that the memo was rewritten to recommend against a grand jury without the author’s knowledge. As Robert Parry reported:

Kellner approved Feldman’s suggestion, but Kellner later rewrote Feldman’s memo and reversed its conclusions. The revised memo disparaged the evidence and claimed a grand jury probe would be nothing more than “a fishing expedition.” Without clearing the change with Feldman, Kellner signed Feldman’s name to the memo and sent it to Washington.

The piece in the Village Voice, helpfully preserved in CIA’s archives, confirms that the memo they received and wrote about recommended against a grand jury being convened.

The theory that the memo was distributed with the hope that it would leak was also put forward by another person the FBI interviewed. He added that he felt that “many copies” of it had been given to authorized DOJ people “in the hopes that someone would leak the memo.” They apparently made a point out of telling people that the memo “contained no federal grand jury material,” which would make leaking it dangerous both for the people connected to the investigation and for the leaker’s career.

While Bergquist’s name is redacted in another version of the memo, one declassified memo cites a memo he wrote as part of the DOJ’s reason for focusing on the OLA, further confirming he was a prime suspect in the leak.

In another instance, a misaligned redaction box reveals Bergquist said that since the Congressional staffer who received it “had a security clearance it would probably not be a criminal violation to turn the memo over to him.”

The DOJ concluded that there was “no reasonable likelihood of proving criminality” and so declined to prosecute. Dissemination of the information was (and continues to be) restricted by the Privacy Act.

The Bureau’s file did note “impediments” to naming anyone as the source of the leak. They never interviewed reporters to confirm the source, nor did they eliminate another possible source of the memo. They were also unable to prove that he “knew” the memo would be leaked as a result of the circumstances they had exploited.

Despite the vagaries of the case, both the FBI and OPR appeared to stand by their admittedly unconfirmed theories months after closing the case, according to a declassified memo from December 1989.

Rather than having his career derailed by the FBI’s unconfirmed suspicions, Bergquist went on to take a number of high profile positions within the Departments of Defense and State, as well as the first President of the Joint Special Operations University and the head of Unconventional Warfare in the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan.

While we’ll have to wait for Bergquist’s death before the Privacy Act will no longer prevent information about the case from being shared, you can read 125 pages from the investigative file embedded below or on the request page:

Image by Another Believer via Wikimedia Commons and is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0