In 1978, a JFK assassination hoax emerged that continues to fuel conspiracy theories and accusations against the Central Intelligence Agency. Two news stories began to circulate claiming that the House Select Committee on Assassinations had obtained an alleged 1966 CIA memo placing Howard Hunt, of Watergate infamy, in Dallas on the day of President John Kennedy’s assassination. Some conspiracy enthusiasts have tried to use the two articles to corroborate each other, unaware that they shared the same source. A review of over 1,000 pages of documents and testimony gives the story of - and dismantles - the HSCA memo hoax.

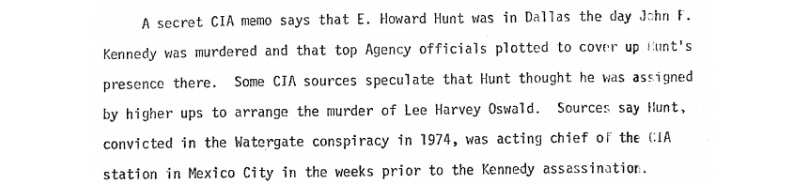

The two articles were published in rapid succession alleging that the CIA was debating what to do about a supposed memo that placed Hunt in Dallas on the day Kennedy was shot. For those looking to blame the Agency, the articles appeared to be excellent corroboration of each other. The first author, Victor Marchetti, was a former Agency insider, leading many to think he might have had friends or friends of friends still in the Agency, giving his claims a certain credibility. The other article, authored by Joe Trento and Jacquie Powers, was published second and became more widely circulated.

In light of the sources for their claims, neither article, however, is credible and neither can be said to confirm the other. The alleged sources for the articles have all disavowed them, one of the authors came to doubt his article and his sources, and both articles had behind the scenes involvement from a journalist known for augmenting his facts with gossip.

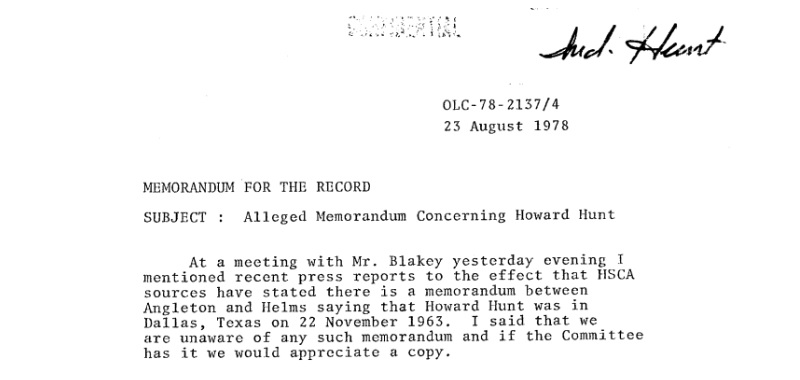

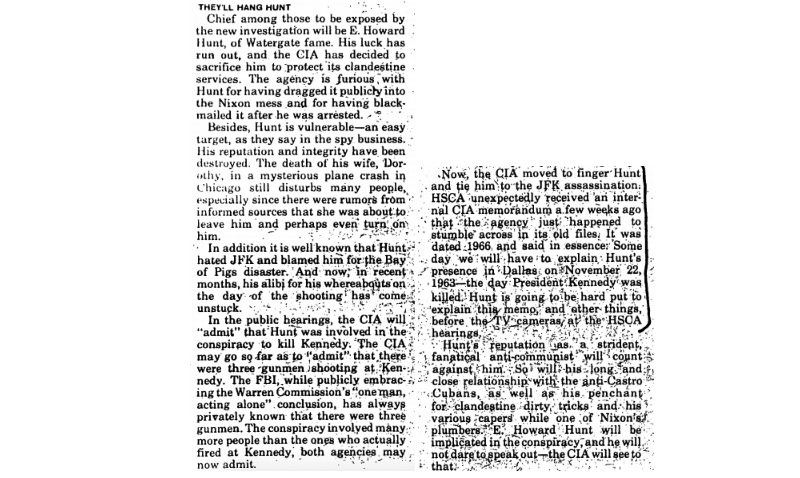

Marchetti’s article, published first, is known for alleging that Hunt was going to be hung out to dry by the Agency in regards to the JFK assassination, using a memo that placed him in Dallas on the day JFK was shot.

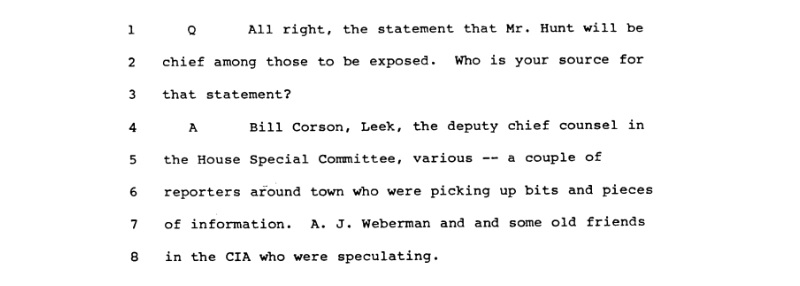

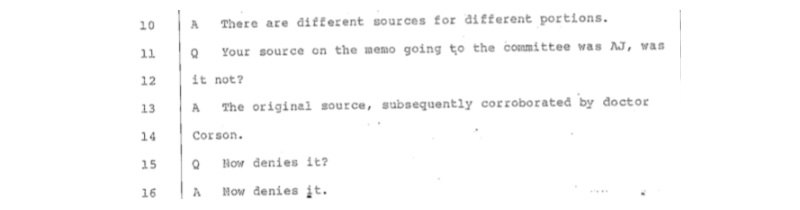

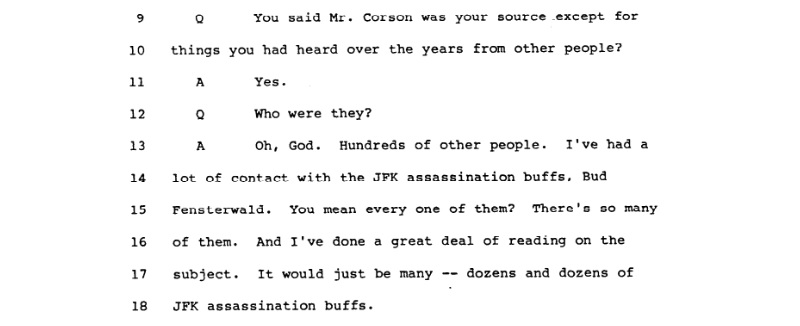

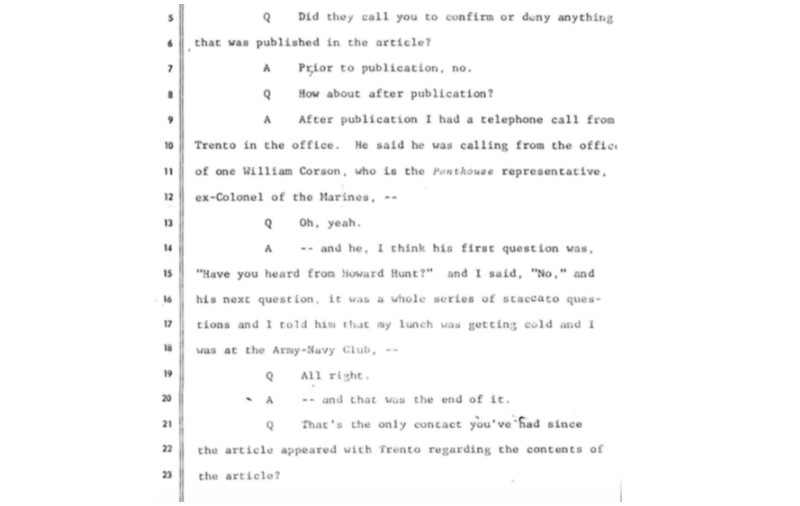

Asked to name his sources under oath, Marchetti cites A.J. Weberman, Bill Corson, unnamed reporters, unnamed friends in the Agency who were “speculating,” and a pair of individuals with the HSCA. As he later makes clear, however, most of these sources contributed little to nothing to the crucial parts of his article.

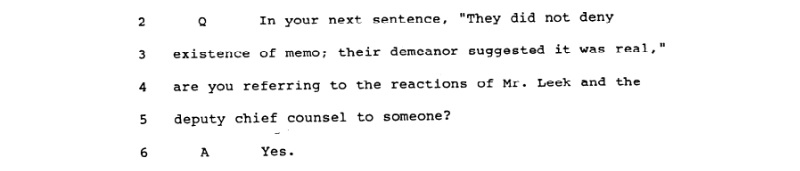

Of those two HSCA sources, Marchetti could only remember who one of them was. The other, according to Marchetti, didn’t actually confirm the memo’s existence. Marchetti said they didn’t deny it existed and an undescribed aspect of their demeanor “suggested it was real.”

In many instances throughout his testimony, Marchetti identifies Weberman as a principle source for many portions of his article. At one point in his testimony, Marchetti credits Weberman with the initial tip about the existence of an alleged Hunt memo.

The information provided by Weberman appears to have been uncertain, and may well have referred to an entirely different supposed memo. Weberman, according to Marchetti, first said that the information was leaked by Gaeton Fonzi, then by Ed Lopez. According to his testimony, Marchetti never spoke to Fonzi or Lopez to confirm the allegations. Subsequently, Weberman would reportedly tell Marchetti that the source was Dan Hardway. In an email to the writer, Hardway emphatically denied this.

Hardway, however, apparently described an entirely different supposed memo. The memo written about in both Marchetti and Trento’s article was dated 1966, while Hardway apparently described a memo from 1976, a discrepancy which even Marchetti felt was significant. Marchetti later called the situation “real messy” and “bullshit.”

As he elaborated in his testimony, Marchetti eventually doubted his own sources, both Weberman and Hardway, as well as what Weberman reported Hardway said (which Hardway denies).

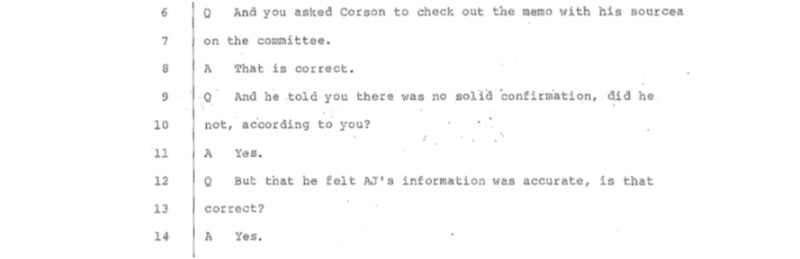

At one point, Marchetti declared that Weberman’s information was corroborated by Corson. Corson denied the conversation ever took place. There’s good reason to question Corson’s denial, given the role that Corson would play in the Trento article.

Although Marchetti testified that Corson confirmed Weberman’s information, when pressed for details Marchetti stated that Corson was unable to confirm its accuracy. Instead, Corson simply allegedly reportedly “felt” it was accurate.

Marchetti stated in his testimony that he felt Corson’s claims were corroborated by “dozens and dozens of JFK assassination buffs.”

In effect, Marchetti’s article relied on a handful of sources. First was Weberman, whose own sources kept changing. Weberman’s claimed final source denied the entire event, with his alleged statement not accurately supporting the central claim of Marchetti’s article. The next source, Corson, would reportedly confirm the information to Marchetti, then report that he “felt” it was accurate, then deny any communication with Marchetti about the case. Marchetti’s sourcing essentially relied on rumors that were best supported by “dozens and dozens of JFK assassination buffs,” many of whom would go on to champion Marchetti’s claims (or pieces of them) to support their own interpretation of the assassination.

Marchetti eventually considered his sources on the story to be “bullshit” at this point, doubting both Weberman (his original source) and the latest person credited with being the source behind Weberman’s claim. For his part, Weberman would allege that James Angleton was the ultimate source for the story as part of a devious disinformation campaign.

Its source was probably James Angleton. Angleton seems to have passed the document on to Corson, who allegedly confirmed its existence for Marchetti and may have shown it to Trento. Somewhere along the line Eddie Lopez heard about it and telephoned me.

Assuming that the document itself actually existed, Trento had to rely on his source’s bona fides for the fact that it was not a forgery. Who could have had better bona fides than Angleton? His name was ON the document.

I believe that Angleton fabricated the document as part of a very clever disinformation campaign aimed at turning the HSCA off to the Hunt/Dallas connection. By creating this document and letting it leak out that the HSCA had it, when they really didn’t, Angleton put the HSCA in a position where they would have to sympathize with Hunt since he had been “unjustly” accused. HSCA Chief Counsel Robert Blakey was quoted as saying, “This memo does not exist. It never happened. It is a lie. The story has done great damage to Howard Hunt.”

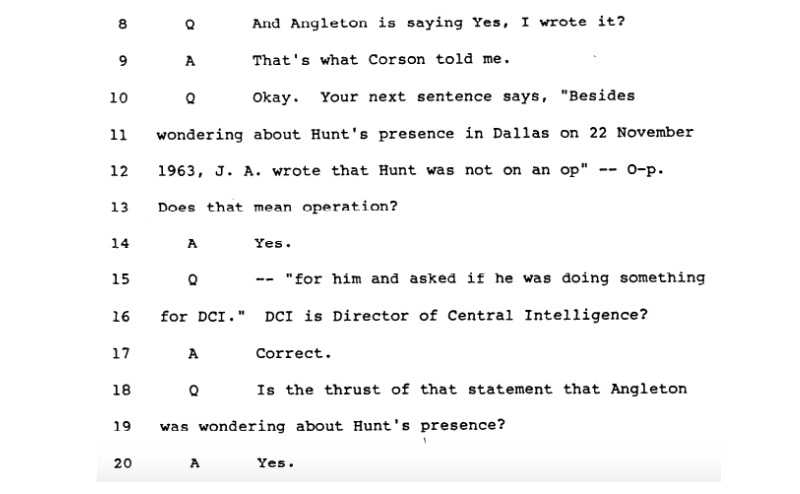

Weberman isn’t alone in fingering Angleton as a source for the article, as Marchetti alleged that Corson claimed he spoke with Angleton about the matter. Angleton would also tie Corson to the articles and to Trento’s work on them, and Trento would eventually claim Angleton as the source for his article. In his public statements as well as in his classified HSCA testimony, Angleton denied being a source for Corson.

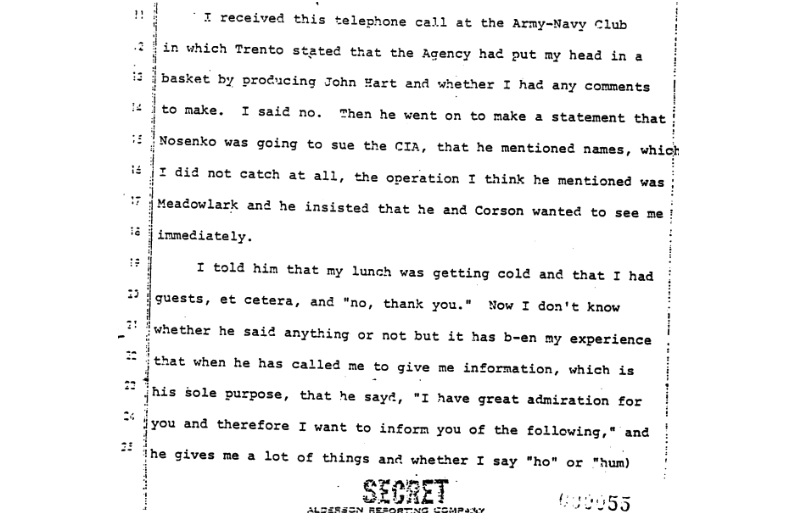

Angleton gave a similar denial in a deposition given as part of Hunt v Weberman, while tying Corson to the affair. According to Angleton, Trento had called from Corson’s office, a plausible scenario since Trento and Corson had a history of working together.

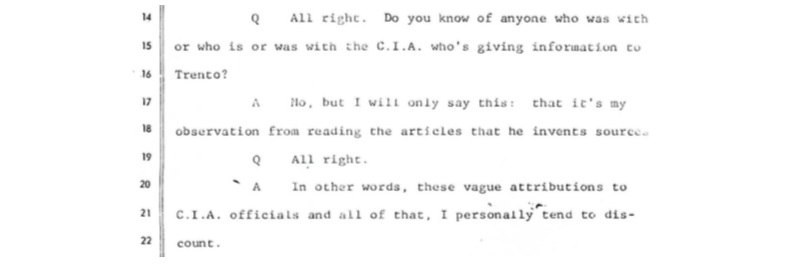

Before Trento told anyone that Angleton was his source, Angleton had accused Trento of fabricating sources.

While Angleton’s version of events are fairly consistent across multiple tellings, Trento’s seem to shift. According to Trento’s original article, Hunt had been the acting chief of station for Mexico City in the weeks before the assassination.

In an online discussion, Trento elaborated by asserting that “Angleton said Hunt was in Dallas not to kill Kennedy but on his way either to or from Mexico City where the Agency had a Station Chief who had been injured in an accident.” Whether these claims came from Angleton or not, they don’t match the documented facts. The CIA Station Chief in Mexico City at the time was Win Scott. Declassified memos give every indication that he was active in the weeks and days leading up to and following the Kennedy assassination. The biography of Scott makes no mention of any injury or being relieved from his role, nor was its author, who had studied this period of Scott’s life in detail, familiar with any such injury.

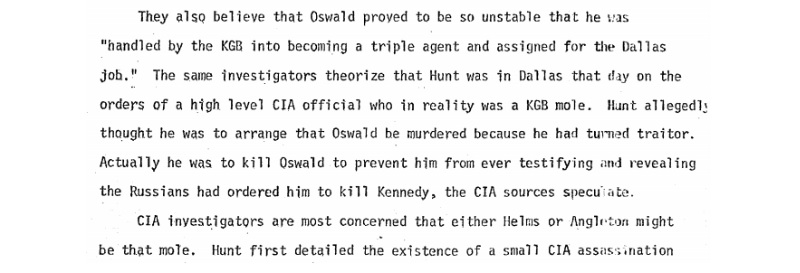

According to Trento’s original article, however, Hunt wasn’t in Dallas because he was traveling “to or from” Mexico City. In Trento’s original version of events, his sources (allegedly Angleton), said that Hunt was in Dallas due to a KGB mole in the Agency, which was suspected to be either Angleton or Helms, referencing (as much of the article does) a number of different stories which have been thrown together in an attempt to imply a cohesive story.

A third version of events is related by Trento to Dick Russell and repeated in Russell’s book, The Man Who Knew Too Much. In the version of events related by Trento to Russell, Angleton told him that Hunt had been in Dallas possibly on the orders of “a high-level KGB mole inside the agency.” After meeting with Trento, Angleton “arranged” for the memo to be delivered to him and to the HSCA using Senator Howard Baker. According to Russell’s book, Trento said “it was all handled in such a way that Angleton was not the source.”

Trento told Russell that he later concluded

“that the mole-sent-Hunt idea was disinformation; that Angleton was trying to protect his own connections to Hunt’s being in Dallas. You see, Angleton was aware of a serious counterintelligence problem with the Cubans. They were making these crazy movements all over Texas and New Orleans. You couldn’t tell who was who, and he knew the exiles were heavily penetrated by Castro’s intelligence … My guess is, it was Angleton himself who sent Hunt to Dallas, because he didn’t want to use anybody from his own shop. Hunt was still considered a hand-holder for the Cuban exiles, sort of Helms’s unhousebroken pet.”

However, this version of events disappeared from Trento’s description before his online discussion, which framed it solely in terms of Hunt being in transit. Also notable is that Angleton had reportedly denied the operational connection to Corson that Trento described when speaking to Russell.

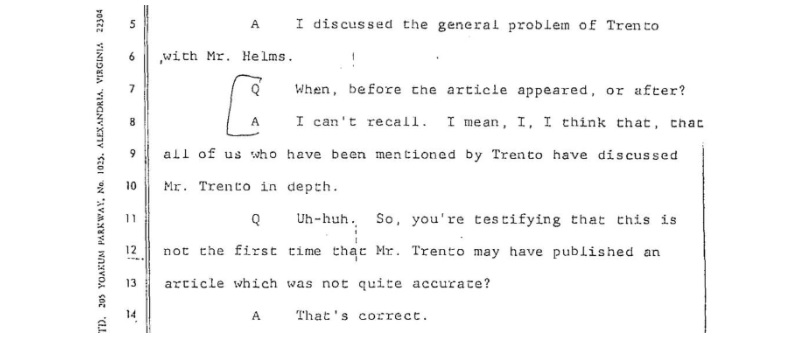

Angleton denied speaking to Trento about the matter outside of a phone call he received at the Army-Navy Club, made from Corson’s office, and during which he declined to comment. In his own testimony, Trento was uncooperative, his answers both minimal and unrevealing. Trento denied remembering the phone call but later told Russell he met Angleton at the Army-Navy Club in person to discuss the matter. Trento also told Russell that Angleton didn’t show him the memo, but was allegedly the indirect source for it.

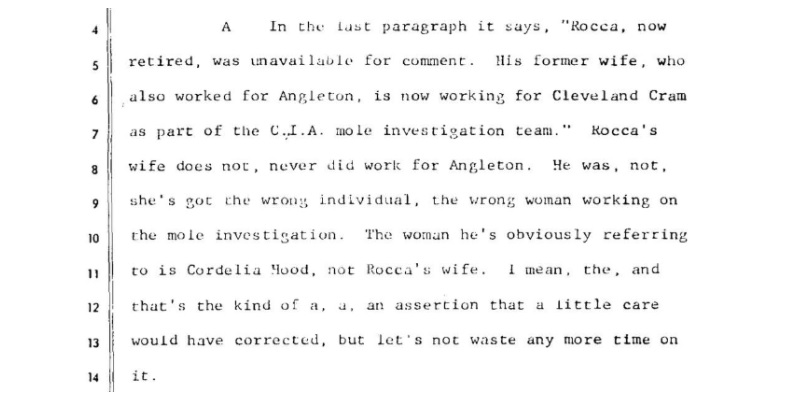

Trento is the only person to claim to see the memo who has stood by the story and their sources, though his version of events has changed over time and whose original article asserted things which are unquestionably false. Trento’s partner played a role in both articles, even acting as a primary source for one. Corson’s denial of any involvement needs to be balanced against his long history of working with Trento as well as both Marchetti and Angleton testifying that he was directly involved. As Corson is tied to both articles and Trento is the only one to stand by the story, it’s necessary to consider both their history together and their credibility.

It was part of their practice to heavily incorporate gossip into their reporting, due to it being “more interesting” than the documented facts. In Trento’s own words, he and Corson bonded because they “agreed that there is a public history codified in documents and official records and there is gossip. It is in the story between those two extremes that one can find a more interesting secret history.” A decade before Trento published the article in question, the FBI accused him of making things up. Angleton later made a similar accusation in his testimony about the matter.

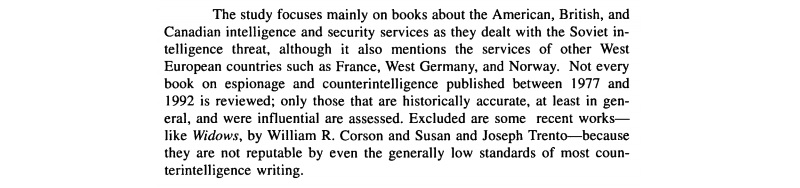

Within the Agency, Trento and Corson are widely seen as not credible. In his review of counterintelligence literature for the Agency, Cleveland Cram ignored their work because it wasn’t “reputable by even the generally low standards of most counterintelligence writing.” Trento dismissed this as mere bias on Cram’s part.

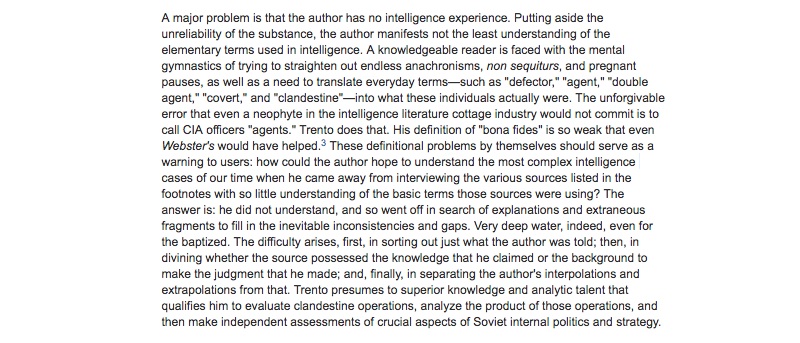

Another former Agency employee, Len M., described Trento’s The Secret History of the CIA, for which he credits Corson as an essential source, as “the worst book yet purporting to provide an account of the Agency’s past.” Len points out that Trento is confused on basic terminology, including repeatedly referring to CIA officers as “agents,” an unforgivably basic mistake. In Len’s words, Trento’s lack of knowledge and experience crippled his reporting even when he did have good sources. “How could the author hope to understand the most complex intelligence cases of our time when he came away from interviewing the various sources listed in the footnotes with so little understanding of the basic terms those sources were using? The answer is: he did not understand, and so went off in search of explanations and extraneous fragments to fill in the inevitable inconsistencies and gaps.”

The Agency’s Intelligence Officer’s Bookshelf is no more kind, calling The Secret History of the CIA “the most inaccurate book ever published on the subject.” While Trento has won his fans in the public sector by making big claims and attributing information and quotes to individuals who are dead and thus unable to contest or clarify Trento’s words, his reception by the research community is mixed at best. His books are full of mistakes, with often vague citations that are unverifiable. As a result, many researchers hesitate to use Trento as a source for anything more than soft corroboration. One well-known intelligence writer, asked privately for their opinion on Trento, said they avoided his work and referred to his work as a barrage of “crap.”

The sources for the story ultimately disavowed it. Only Trento actually claims to have seen the memo, citing a now deceased source who had previously denied it, and telling inconsistent versions of that story. Trento admitted to Russell that he eventually concluded at least part of what Angleton allegedly told him, and what he printed, was disinformation. What Trento claims Angleton told him is provably false, which would have been easy for anyone at the CIA or HSCA to prove.

Marchetti said he considered the situation “bullshit” and that he eventually had trouble believing his sources, despite having consulted “dozens and dozens of JFK assassination buffs.” Marchetti said he got information from Corson and that Corson had said he got it from Angleton. Corson and Angleton denied this under oath, though Angleton said Corson was working on the story with Trento. Trento denied remembering the phone call Angleton twice described, but later claimed Angleton had been his source. The first story’s original source, Weberman, wrote that he concluded the whole thing was disinformation to deflect from something worse. Weberman’s sources changed repeatedly, with all of them denying the information at one point or another.

By his own admission, Marchetti relied on rumors for his story - the same territory of gossip in which Trento and Corson deliberately operated, which resulted in their article becoming a mishmash of facts and only tangentially related narratives.

Yet some still take the articles seriously, often ignoring some of the inconvenient or false claims made in Trento’s article. While some contend that they corroborate each other, the role that Corson appears to have played in both articles raises serious questions about whether or not they were independent enough to truly corroborate one another.

The narrative of the articles likely persists because they fit into the world view and thesis of those that support them - typically that the CIA is den of thieves, and that either the Agency or a rogue faction of it was responsible for Kennedy’s assassination. This narrative persists because there are many people who prefer the “more interesting secret history” that Trento offers by consulting gossip and supposition as much as he does verifiable fact. The truth is most certainly less interesting, and for those inclined to believe Hunt was in Dallas when Kennedy was killed, it’s less appealing.

However, the truth’s job isn’t to be interesting. it is simply to be the truth. And though both the JFK assassination and CIA history are full of underexplored interesting bits of history, in this case, the truth is that the memo almost certainly never existed and that the rest is just a mishmash of narratives.

You can read the transcript of the Hunt v Spotlight lawsuit over Marchetti’s article below, or find other relevant testimony here.

Image by Jack White via jfkassassinationgallery.com