With nationwide protests calling for the abolishment of Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and counter-charges alleging that such movements are the work of sinister foreign agents intent on sowing discord, it’s worth revisiting a similar period in American history when the Federal Bureau of Investigation framed opposition to House Un-American Activities Committee as Communist agitation - and faced pushback even within its own ranks.

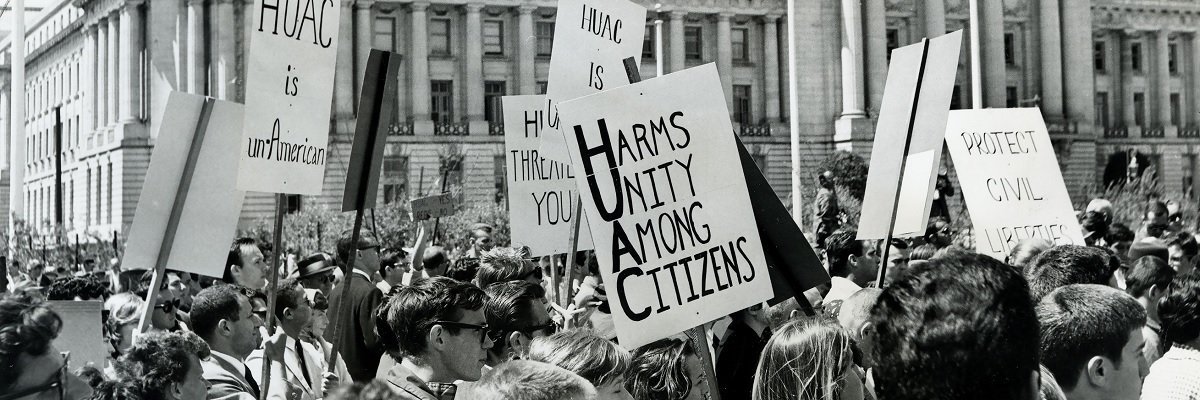

In May 1960, HUAC held hearings at San Francisco City Hall. Housing official and activist Frank Wilkinson, who had previously been called before HUAC, organized a protest as part of a campaign to abolish HUAC. Though the exact sequence of what happened next is in dispute, at some point the San Francisco Police Department turned fire hoses on the demonstrators, and the protest, as the saying goes, “got violent.”

HUAC was quick to blame the violence on “Communist agitation” and used newsreel footage to create the propaganda film “Operation Abolition: The Story of Communism in Action.”

Arguing that the film’s presentation of events was lopsided at best, the American Civil Liberties Union responded in kind with “Operation Correction,” which gave a much different account - one in which the police were the clear aggressors.

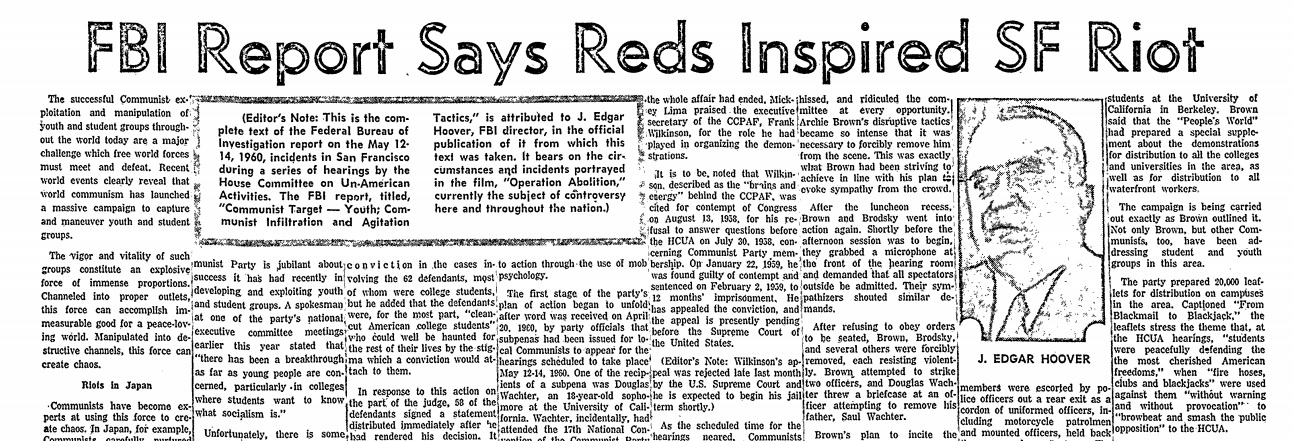

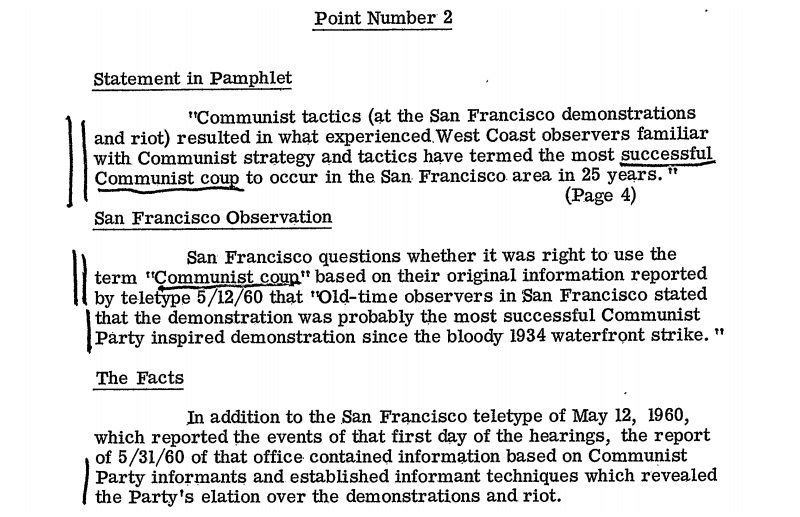

When national outlets such as the Washington Post followed suit with their own investigations into the veracity of “Operation Abolition” claims, the FBI decided to step in. Director J. Edgar Hoover personally published a report entitled “Communist Target - Youth,” which purported to contain conclusive evidence of a Communist plot behind the protest, which was now being billed as a full-fledged riot.

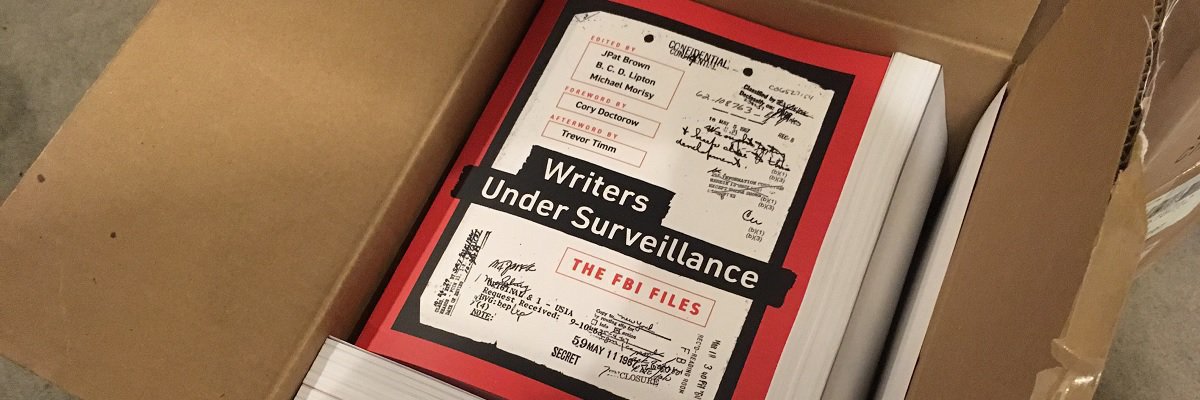

As files released to Conor Skelding show, however, Hoover soon found himself facing some pushback on the report (which had been converted by HUAC into a easily-distributable pamphlet) from an unexpected source: the San Francisco field office which had originally provided the material the report was based on.

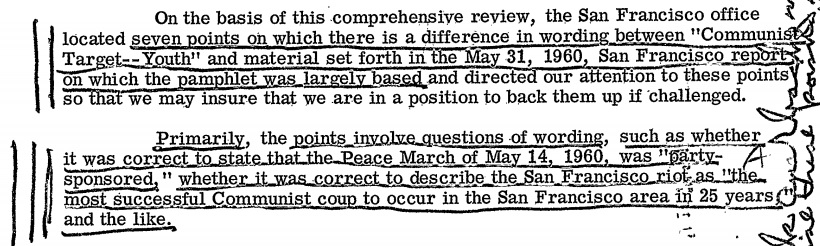

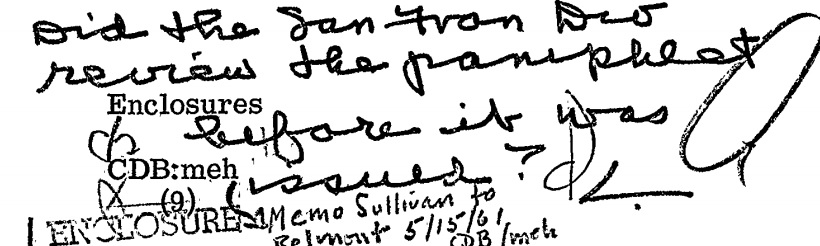

A May 1961 memo from William “Bill” Sullivan, the FBI’s domestic intelligence chief often considered Hoover’s chief rival within the Bureau, outlines seven areas of dispute between what the San Francisco field office had provided and what Hoover had published. Characteristically, Hoover was infuriated by this perceived insubordination, demanding to know if these concerns were only being voiced after the report had been published …

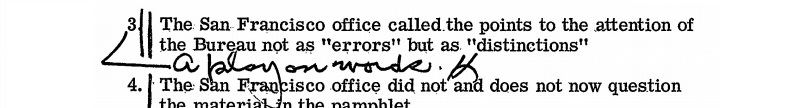

and bitterly dismissing as a mere “play on words” the office’s attempts to clarify that they weren’t necessarily accusing Hoover of having gotten anything wrong.

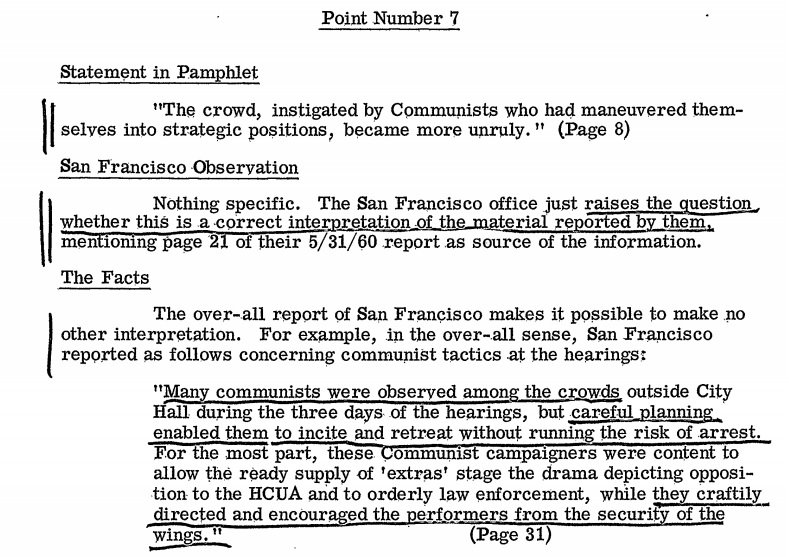

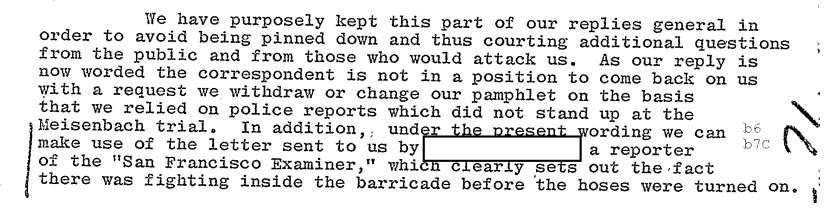

A subsequent analysis considered and then consequently dismissed the seven concerns raised by the memo, each time the San Francisco field office politely suggesting that perhaps the report went too far and Hoover’s office countering with perhaps they didn’t go quite far enough.

Ultimately, the Bureau decided against issuing any corrections or retractions, but in many ways, the damage was already done - rumors had already begun to spread that the FBI was trying to distance itself from the report …

and a later version of “Operation Abolition” that strongly appealed to the authority of “Communist Target - Youth” became a subject of embarrassment when several of the police reports cited fell apart in court.

Hoover was never one to forget a slight, and clippings from the file show that he took the matter personally.

In the years to follow, the gulf between Hoover and Sullivan grew wider, and Sullivan grew more vocal in his criticism of what he felt was the Bureau’s overestimation of the threat from Communism. That came to a head in 1971 when Hoover forced Sullivan into retirement by locking him out of his office - a move that would have been the final straw leading to Hoover’s own forced stepping down had Hoover not simplified the matter by dying.

Read “Communist Target - Youth” embedded below and the internal discussion over on the request page.

Image via the San Francisco Public Library