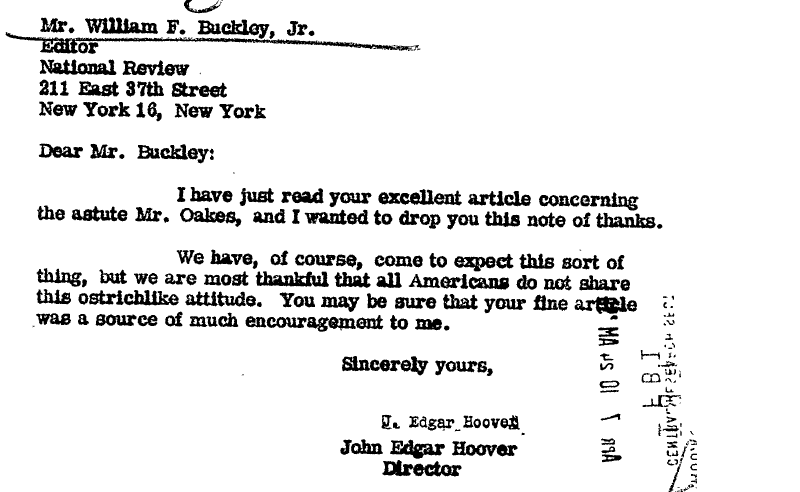

Author and journalist William F. Buckley, Jr. is an icon of American conservatism, quite literally defining the political philosophy in the very first issue of his seminal magazine, National Review. Buckley’s nearly 40-year relationship with the FBI began back in 1950, when J. Edgar Hoover himself was urged to meet with the then twenty-five-year-old phenom.

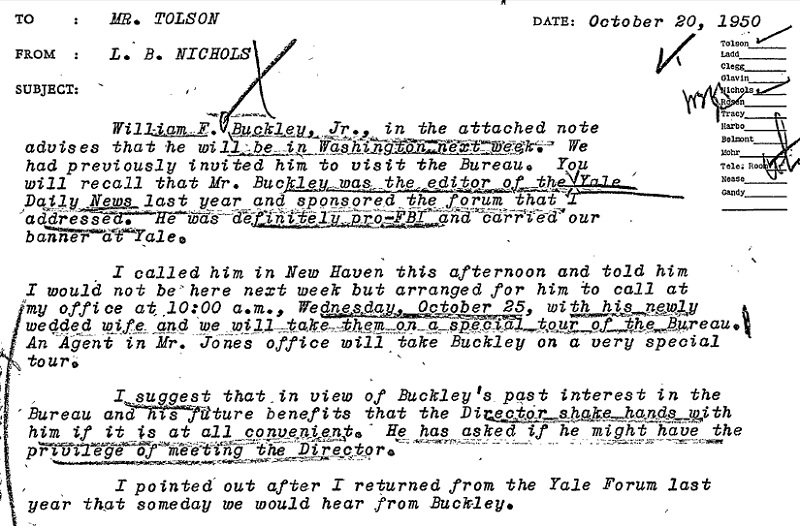

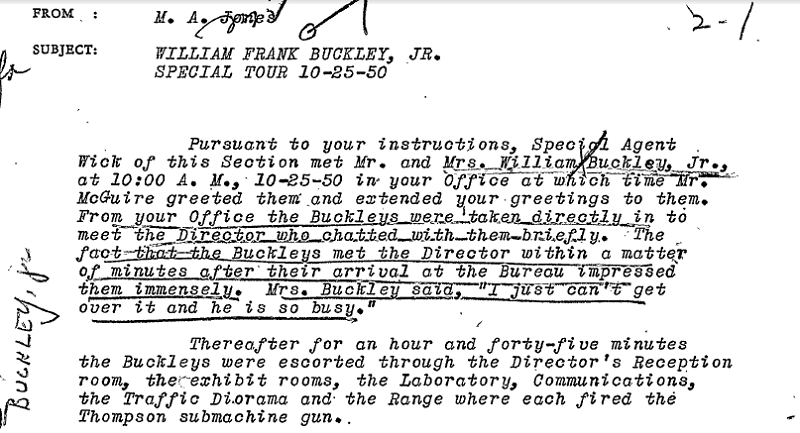

FBI Assistant Director Louis Nichols first met Buckley the year prior at a Yale forum on law enforcement and, after repeatedly noting that Buckley was “decidedly pro-FBI,” managed to convince Hoover to agree to the meeting. Hoover even granted Buckley and his wife a special tour of the Bureau, complete with a trip to the firing range.

This visit and the (for Hoover) lifetime of correspondence to follow was documented in Buckley’s FBI file, which was recently released to MuckRock’s Beryl Lipton following a Freedom of Information Act request.

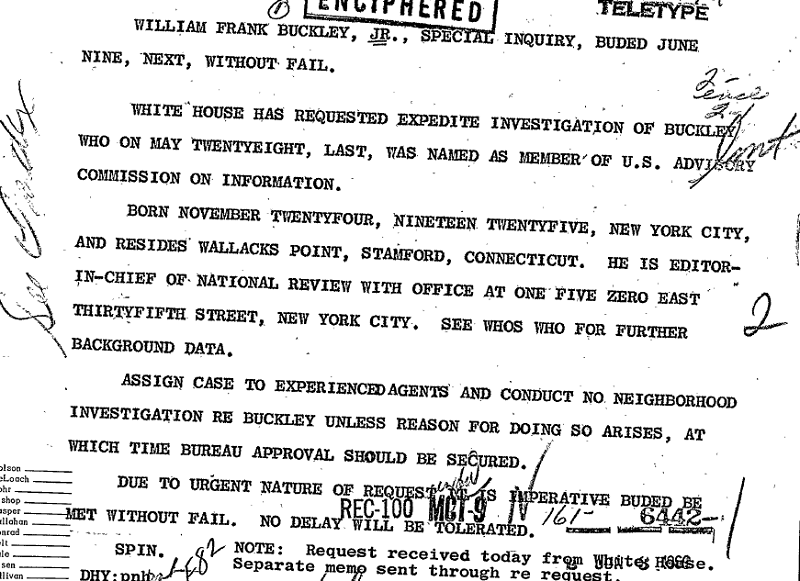

The file is broken up into four parts, the largest being made up of a series of background checks prompted by Buckley’s (apparently, rather rushed) appointment to the United States Information Agency Advisory Commission by President Nixon.

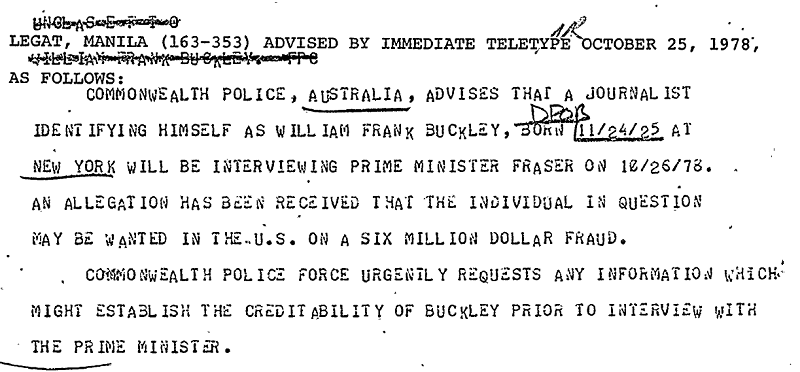

While two smaller parts consist of assuring the Australian government that Buckley isn’t a known felon …

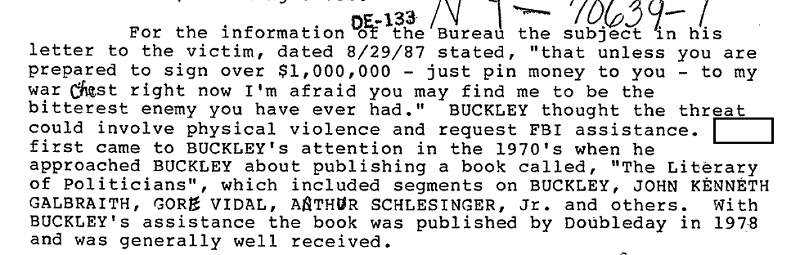

… and dealing with threats made by a disgruntled former National Review columnist.

Of special note on the former - while the name of the suspect is withheld under the b(6) exemption, the book they wrote is not (albeit with an misnamed title), so determining their identity is the matter of a simple Google search.

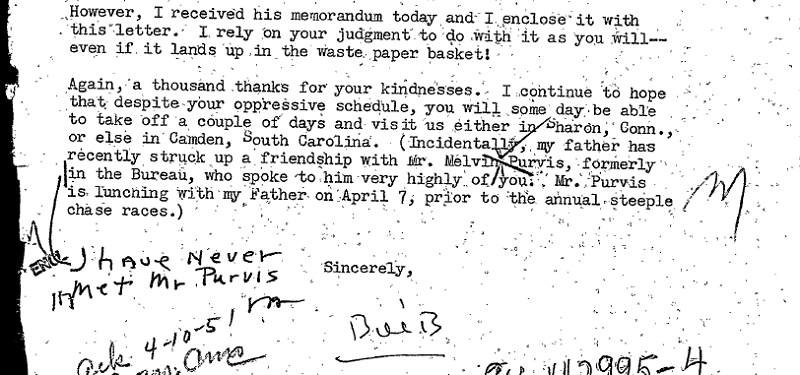

The last part is by far the most interesting; it contains the aforementioned correspondence between Buckley and the Bureau over the years. In the early ’50s, Buckley wrote mostly to Nichols, and while it does appear that the youthful Buckley’s enthusiasm might have come off as somewhat grating …

Nichols was nonetheless very supportive and helped facilitate his budding relationship with Hoover, which picked up right as Buckley’s National Review work was hitting its stride.

The file even notes that the Bureau has “limited but cordial relations with Buckley,” which for Hoover is high praise.

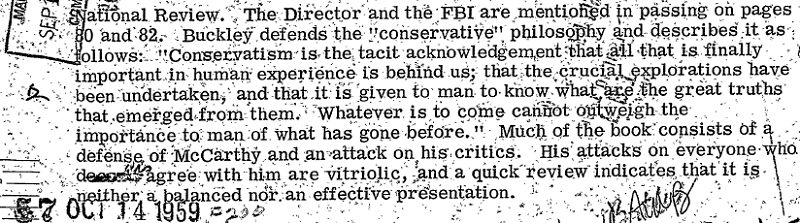

Despite these (relatively) warm relations, Buckley was not immune to the Bureau’s criticisms, and a note attached to a signed copy of Up from Liberalism gifted to the Director witheringly states that it is “neither a balanced nor an effective presentation.”

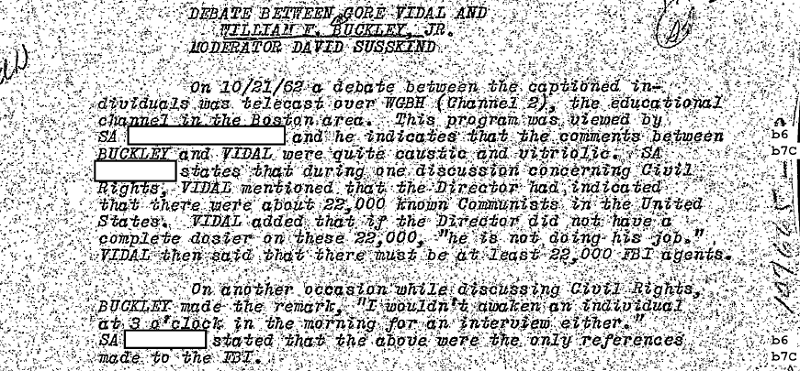

“Vitriolic” is a running theme in the file, coming up once again in a special agent’s description of one of Buckley’s famous verbal bouts with Gore Vidal.

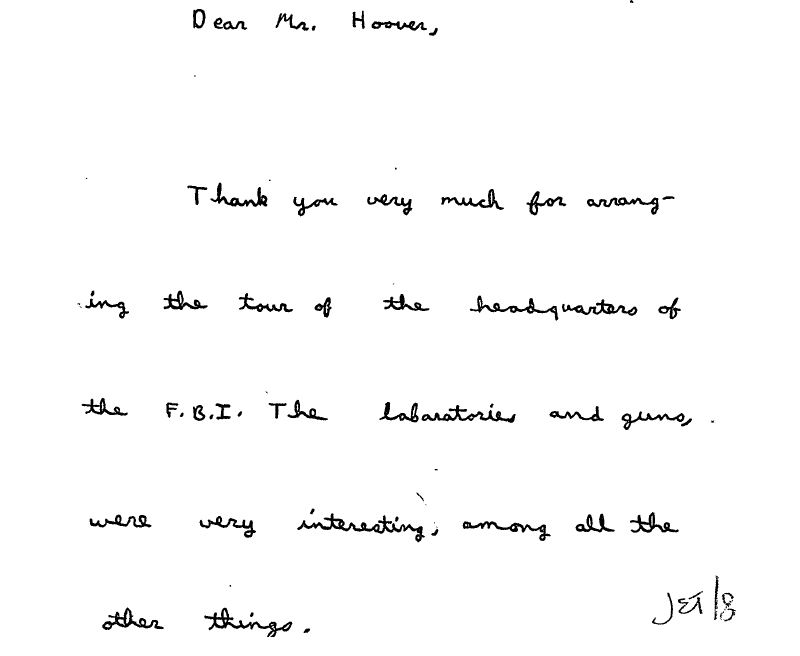

Twelve years after his own visit, Buckley brought his ten-year-old son - the future novelist Christopher Buckley - on a similar special tour of the Bureau. Included in the files is Christopher’s adorable handwritten note …

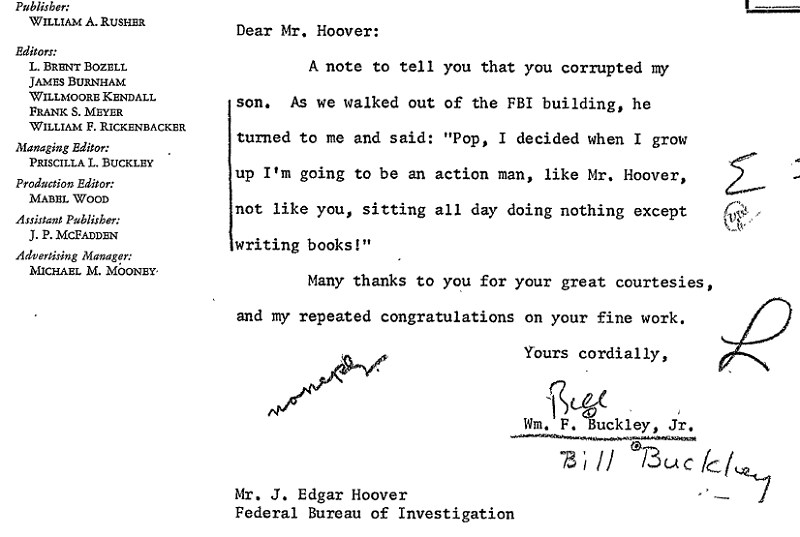

As well as a letter from Buckley playfully admonishing the director for “corrupting my son.”

Judging by Christopher’s later profession, though, that “man of action” thing didn’t really stick.

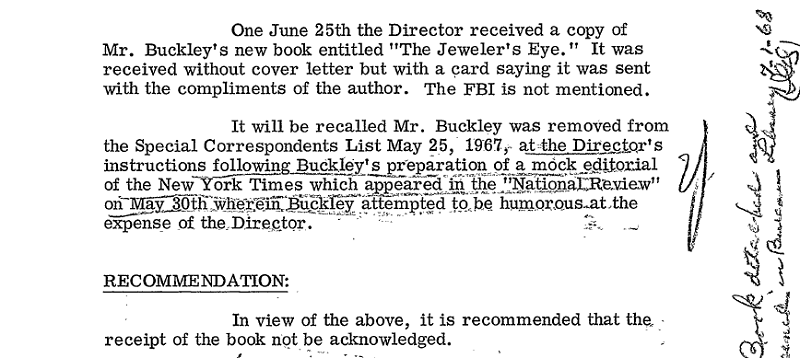

Unfortunately for Buckley, all those years of goodwill between him and the Bureau were ultimately undone by Hoover’s notoriously thin skin. In the May ‘67 issue of National Review, Buckley wrote a parody article in the style of the The New York Times, lampooning the Gray Lady’s critical coverage of the Director. Hoover was not amused and even considered legal action for defamation of character.

Despite Buckley’s repeated insistence that the article was actually in support of Hoover, their relationship never fully recovered. Buckley was removed from the Special Correspondents List, and though he continued to send Hoover signed copies of all his books, the Director’s thank you notes stopped coming.

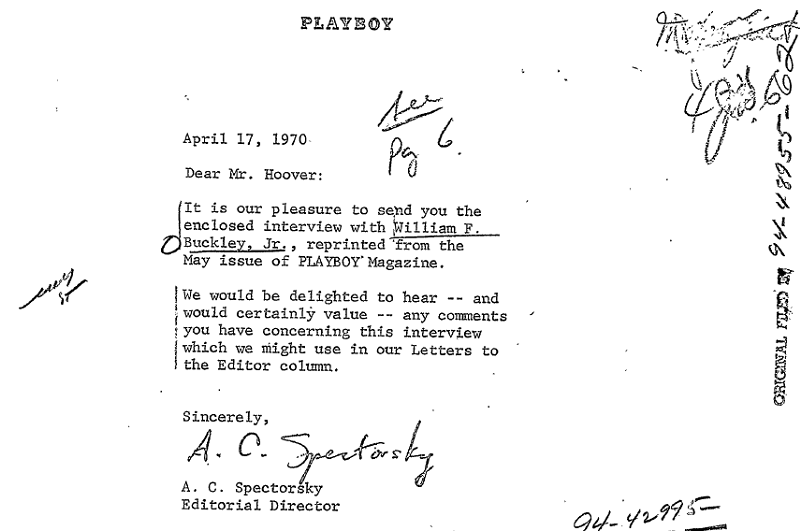

The editors at Playboy magazine were apparently unaware of the bad blood and sent Hoover a nudity-free clipping of their May ‘70 interview with Buckley, cheekily asking if he’d have any comments for their Letter to the Editor column.

Though the interview is included in its entirety in the file (I FOIA for the articles), there is no indication that the Director ever responded to Playboy.

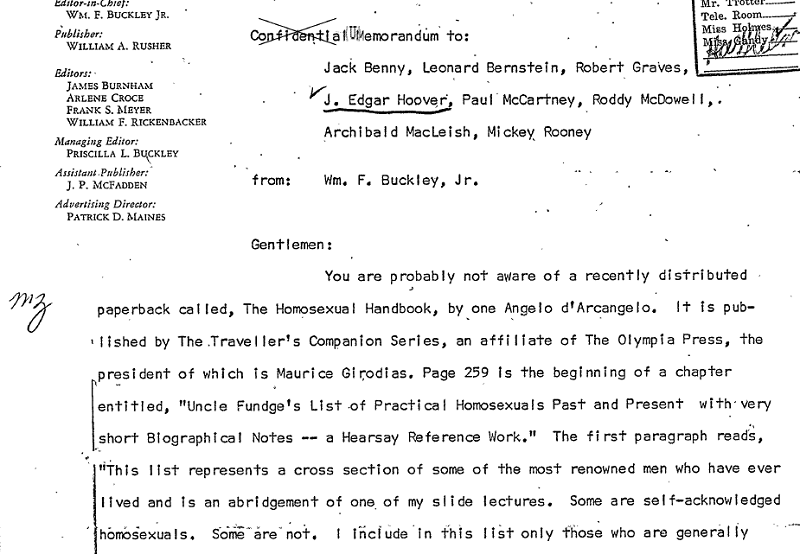

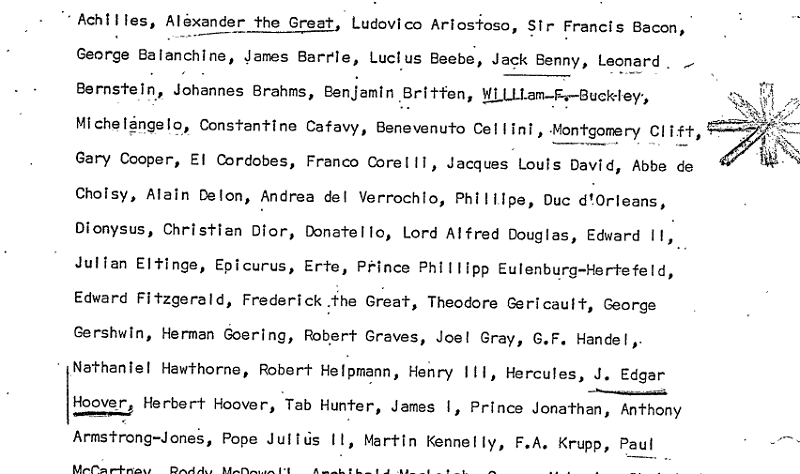

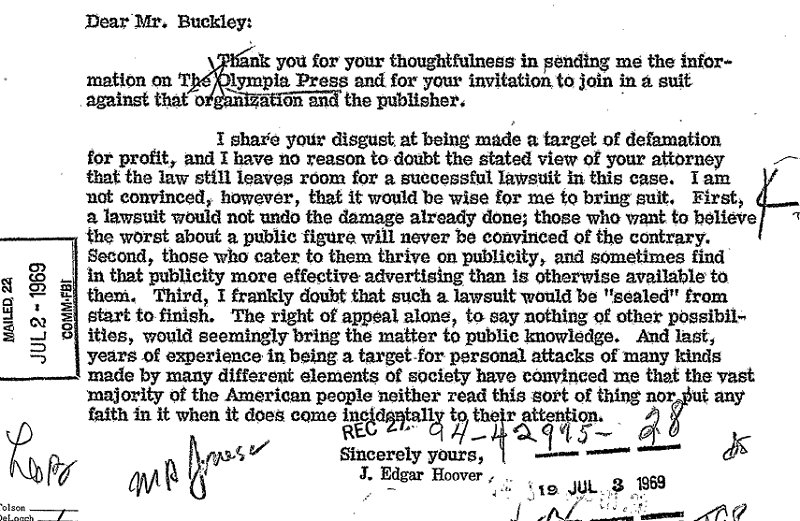

Formal communication was established once again when Buckley reached out to Hoover - along with a handful of other public figures including Jack Benny and Paul McCartney - over the possibility of filing a joint lawsuit against Olympia Press, publisher of the The Homosexual Handbook, which included them both in their list of “Practical Homosexuals, Past and Present.”

Hoover actually cautioned Buckley against the suit, saying that the damage had been done, additional attention would only make things worse, and that the vast majority of the American public “neither read this sort of thing nor put any faith in it.”

Their relationship, though never as strong as it was once was, warmed considerably after the incident.

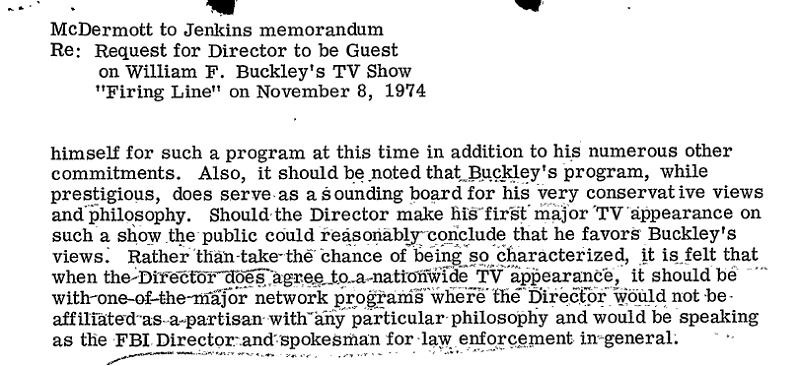

Two last instances in the later years stand out. The first is Hoover’s successor, Clarence Kelly declining Buckley’s offer to appear on his long-running PBS show Firing Line, noting that such an appearance would be tantamount to the Bureau’s endorsement of Buckley’s Conservatism.

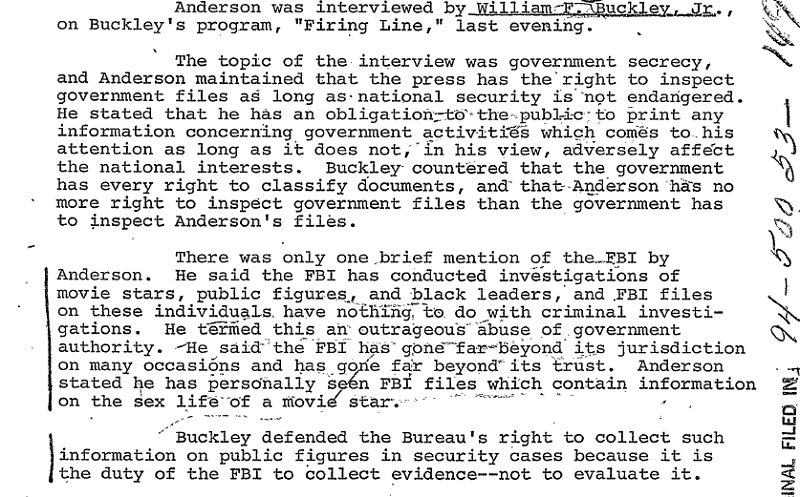

The other is a special agent’s report on an episode of Firing Line in which Buckley both defended the FBI’s right to keep files on whoever they so chose and to keep those files out of the prying hands of journalists.

In a fitting tribute, we’ll leave Buckley with the last word.

The correspondence file has been embedded below, and the rest can be found on the request page.

Image via the FBI