New Central Intelligence Agency documents shed light on the agency’s authority to partner with domestic law enforcement agencies. These procedures appear to give the green light for such programs as the development of aerial cell phone trackers in collaboration with the US Marshals.

Last November, the Wall Street Journal first disclosed a US Marshals surveillance program that uses cell site simulators mounted on airplanes to track down suspects on the run. In March, WSJ uncovered that the CIA is a key partner in the program, having provided millions in funding and equipment transfers to the US Marshals over more than decade.

People familiar with the operation told WSJ that the program was fully functional as of 2007, and that the US Marshals currently operate Cessna aircraft equipped with “dirtbox” cell phone trackers on a regular basis from at least five metropolitan-area airports. Officials characterized the collaboration between the US Marshals’ Technical Operations Group and the CIA’s Office of Technical Collection as a “marriage.”

A CIA spokesperson declined to confirm any specifics. Although he disputed the “marriage” description, he told WSJ that some equipment developed by the CIA “have been lawfully and responsibly shared with other U.S. government agencies.”

“How those agencies use that technology is determined by the legal authorities that govern the operations of those individual organizations — not CIA,” the spokesperson said.

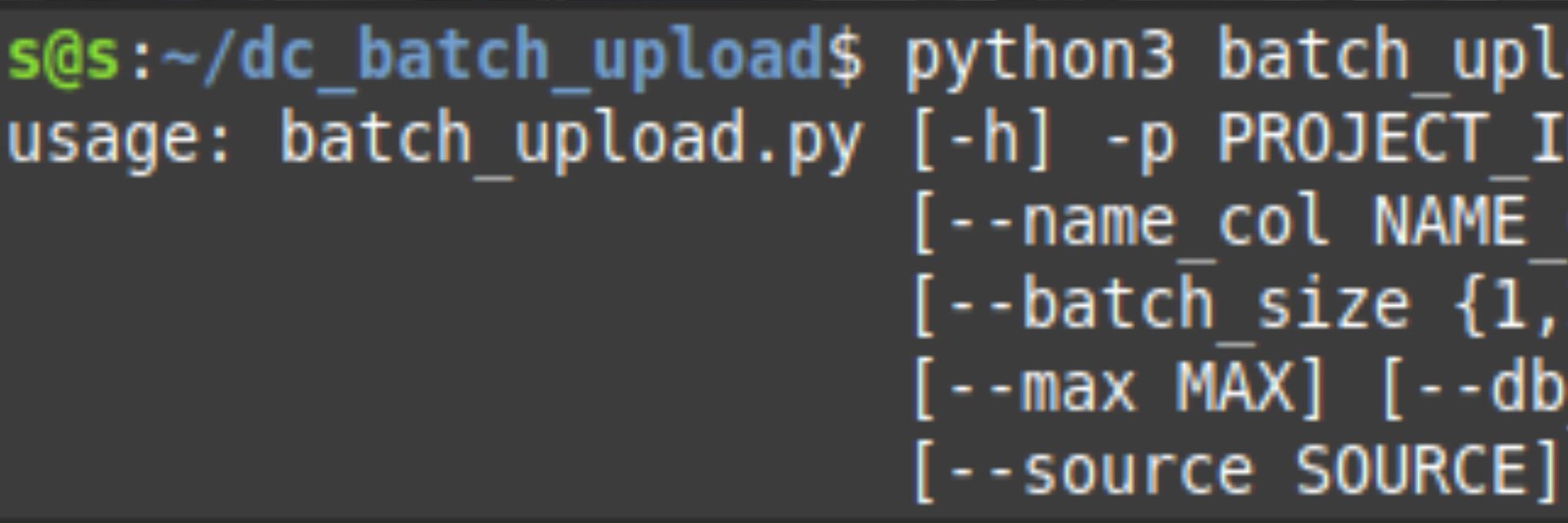

Federal law bars the CIA from collecting intelligence within the borders of the United States except under particular circumstances. But internal rules and procedures published last week outline how the CIA can provide training and “specialized equipment” to domestic law enforcement agencies such as the US Marshals.

The CIA procedure documents were obtained by the American Civil Liberties Union as part of an ongoing Freedom of Information Act lawsuit in partnership with the Media Freedom Information Access Clinic at Yale Law School. In May 2013, the ACLU requested documents regarding the CIA’s interpretation of Executive Order 12333, which was signed by President Reagan in 1981. The order divvies up intelligence collection responsibilities among various federal agencies and establishes oversight procedures for the intelligence community.

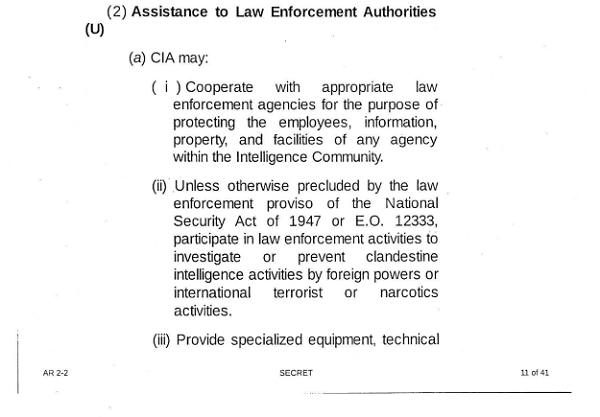

Under EO 12333, the CIA may provide “specialized equipment, technical knowledge, or assistance of expert personnel” to other federal agencies. In emergency cases when lives are endangered, the order authorizes the CIA to give the same assistance to local law enforcement agencies.

As a public executive order, the text of EO 12333 has been public since its signing. But the order requires intelligence agencies to develop more specific implementation procedures, which are approved by the Attorney General. Until their release under the FOIA lawsuit, the CIA’s implementation procedures for EO 12333 remained secret.

Beyond joint actions to protect its intelligence personnel and to investigate foreign spying, terrorism, or narcotics activity, Agency Regulation 2-2 dictates that the CIA’s Office of General Counsel must approve all partnerships with domestic law enforcement agencies.

The newly released regulation’s wording mirrors that of EO 12333’s provision of “specialized equipment, technical knowledge, or assistance of expert personnel” to federal agencies, and to local law enforcement under emergency conditions. The CIA regulation also allows agents to provide “generalized training” to law enforcement personnel, whether for federal, state or local agencies.

Such “specialized equipment” appears to include cell site simulators and other technologies that help law enforcement to track or locate mobile devices. The CIA did not return a request for confirmation as to whether the agency relies on these provisions for its collaboration with the US Marshals.

The CIA thus has the authority to train other law enforcement agencies on surveillance techniques for domestic deployment. The CIA can provide the buttons and show which ones to press, but only so long as their agents aren’t pushing the buttons themselves.

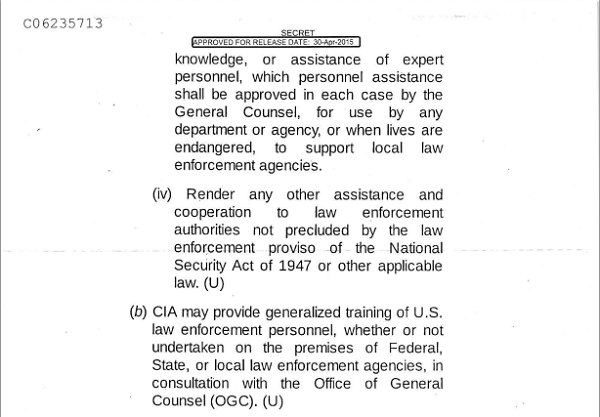

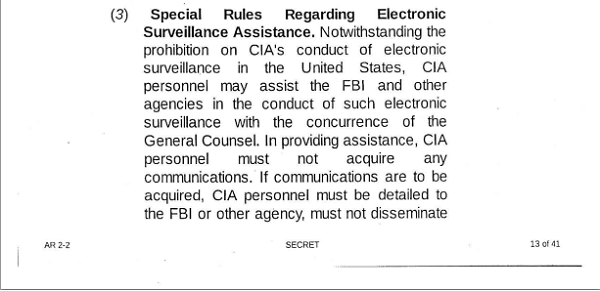

Under a dedicated section of the regulations, CIA agents may assist other law enforcement agencies with electronic surveillance abroad. A separate annex which governs CIA activities within US borders bars agents from directly participating in “the collection of raw information” in domestic operations.

But the definition of “electronic surveillance” as found in EO 12333 and the CIA regulations may not cover StingRays and other devices that law enforcement use to track cell phones.

Under the executive order, electronic surveillance is “acquisition of a nonpublic communication by electronic means without the consent of a person who is a party to an electronic communication […] but not including the use of radio direction-finding equipment solely to determine the location of a transmitter.”

An appendix to the CIA regulations expands on this definition to encompass “telephone surveillance, microphone (audio) surveillance, and signals intelligence (SIGINT).” But the appendix definition likewise excludes “the use of radio direction finding equipment solely to determine the location of a transmitter.”

A StingRay might qualify as “radio direction finding equipment,” and so fall outside the CIA”s proscription against electronic surveillance on US soil. Other agencies such as the FBI, on the other hand, classify cell site simulators as an electronic surveillance tool.

Similarly, the regulations detail how, if the general counsel signs off, CIA agents may use “monitoring devices” within the United States “under circumstances in which a warrant would not be required for law enforcement purposes.”

The heavily redacted definition in the CIA appendix hardly helps to clarify whether cell site simulators qualify as monitoring devices.

If the CIA does consider StingRays to fall within the “monitoring device” moniker, the question remains whether agency lawyers consider their deployment to require a warrant. Justice Department lawyers held for more than a decade that no warrant was necessary to use a StingRay, and only recently did the FBI begin to seek warrants for cell site simulator deployments.

Here, again, the regulations and other documents released by the CIA don’t provide definitive answers.

Image via CIA.gov