This is the first in a four-part series on the killing of Orhan Gündüz, a low-level Turkish diplomat living in the Boston area caught up in an international assassination ring. Read chapter 2, chapter 3 and chapter 4.

For years, Orhan Gündüz’s small gift and import shop was a gathering place for Turkish expatriates, tucked away in the center of Cambridge’s Central Square, across the Charles River from Boston. But by the spring of 1982, Topkapi Imports had become a deadly target for Armenian terrorists waging a violent campaign against Turkey, and each new face entering Orhan’s shop posed a potential threat.

From the back of his store, which was filled with hand-woven rugs, exotic jewelry and Turkish dresses, Orhan doubled as a low-level, unpaid diplomat, who nonetheless looked the part of an ambassador with his formal suits. He helped Turkish nationals in need of visas; translated documents from English with his wife, Meral; and welcomed exchange students who wandered in seeking a familiar face from home. The work often kept him up through the early morning hours.

Orhan had no police protection, despite requests by his congressman to the FBI. When he left his shop just after 6 p.m. on May 4, 1982, he did so in a hurry and alone, despite repeated warnings from friends and family who feared for his safety.

Driving home, his white, 1977 Ford LTD inched through traffic heading toward Interstate 93, crossing the town line from Cambridge into working-class Somerville. On the way, he passed the vestiges of Somerville’s once-bustling industrial corridor: graffiti-tagged garage doors of auto repair shops; barbed fences of a scrap yard; multi-family, vinyl-clad homes; and used car lots with sun-faded, multi-colored banners.

At around 6:30 p.m., Orhan’s car, which had consular license plates, approached a bridge across from a brick-faced Catholic school, at the mouth of Union Square. He eased to a stop at the intersection of Webster Avenue and Newton Street, boxed in by rush-hour traffic.

Someone was waiting for him.

A jogger — described as a slim, young man with dark hair, a royal blue tracksuit and dark aviator sunglasses — stepped out in front of Orhan’s car.

In one bizarre, fluid movement, the jogger lifted one arm straight up in the air and, with the other, pointed a 9 mm pistol at Orhan’s windshield.

He shouted, according to eyewitnesses:

“Now for the cannon!”

He fired 13 rounds at the windshield, striking Orhan nine times, at least twice in the head. Orhan died instantly; his car rolled forward down the sloping residential street 50 yards before hitting a chain-link fence.

Throwing aside his sunglasses, track jacket and two guns, the jogger fled into the busy square.

Leads were thin. Eyewitnesses gave varying accounts, some mentioning seeing multiple joggers matching the shooter’s description in the vicinity, while others only saw one.

Within hours, the FBI had taken over the crime scene, but witnesses grew silent. Somerville, the birthplace of the notorious Winter Hill Gang, was still struggling with its own criminal element. Residents knew the deadly cost of speaking out. The Boston Herald reported that a man claiming to be a witness to Orhan’s murder was gunned down along the railroad tracks near the original crime scene months later. Never corroborated, the story persists to this day.

For 40 years, the FBI has kept its file on Orhan Gündüz locked away, leaving scattered breadcrumbs across dozens of other previously-released files. A request for the full FBI file on Orhan has remained unreleased for almost a decade — and counts as MuckRock’s oldest outstanding request.

The FBI codenamed the case KAPIKILL.

Now, thousands of pages of newly-published FBI documents obtained by MuckRock show U.S. law enforcement agencies spent considerable resources identifying the culprits. Agents found the discarded tracksuit, tracked down the getaway car and even hypnotized witnesses to get more details. The FBI’s Boston and Los Angeles offices coordinated an elaborate bicoastal investigation involving a network of high-risk informants and a multistate gun trace on the murder weapons, in an urgent bid to prevent another attack.

Over the past nine years, we have sought public records on the assassination of Orhan Gündüz from the CIA, FBI and State Department and contacted family, friends, colleagues and law-enforcement officials, trying to piece together the subsequent investigation. Last year, the FBI released roughly 4,000 pages of its internal files to us, which we are now making public for the first time. (See the documents here. We’ll be releasing additional records with future installments.)

Those records, though incomplete, offer a fuller and previously unseen glimpse at how a small group of terrorists put the Armenian genocide on front pages, killing 31 Turkish diplomats and their family members across the world, including two in the U.S. They also show, for the first time, that the FBI believed they had uncovered the identity of the young man in the blue jogging suit and his associates, but no one would ever be charged for Orhan’s murder.

While the most important question — who the FBI believed killed Orhan Gündüz — has gone unanswered until now, the motive became clear before the bullet-ridden car was towed away. Shortly after the assassination, the Los Angeles bureau of United Press International received a phone call:

“I’m calling on behalf of the Justice Commandos of the Armenian Genocide,” the caller said. “We just shot the Turkish consul in Boston, Massachusetts. This is our style. We will strike again.”

Within the released files are FBI memos that show, by the end of 1982, five of the men allegedly associated with the terrorist group — including Orhan’s possible shooter — would be linked to a separate bomb plot that the FBI feared would be among the worst terrorist attacks ever on American soil.

Forty years later, some of those men are still alive, living in the U.S. and enjoy continued support from Armenian-American community groups.

What preceded Orhan’s 1982 killing and the rumors of a key witness being gunned down would, to outsiders, become part of a mystery that involved shadow assassins, martyrs, survivors and geopolitics at the center of a century-old battle. For a small and tight-knit Armenian community, those assassins were pursuing their own version of justice.

‘They will plan their revenge’

In 1915, Ottoman soldiers rounded up and killed Armenian intellectuals and leaders as a first step in a campaign to remove Armenians from what would become Turkey. Their brutal methods included marches to nowhere designed to starve women and children. There were reports of a bonfire being lit at the mouth of a cave to suffocate thousands seeking shelter from the desert. In one particularly ruthless episode, 4,000 Armenians were shot by Turkish forces in a gorge now referred to as “Massacre Canyon.”

Responding to concerns from U.S. Ambassador Henry Morgenthau about violence against Armenians, Ottoman leader Talaat Pasha said the goal was “to finish with them” – otherwise “they will plan their revenge.”

Most estimates by historians put the total dead at around 1 ½ million.

While widely reported at the time, the newly established Turkish republic of the 1920s rewrote its own history, lamenting its wartime struggle rather than focusing on the genocide. While a new Turkish government focused on building a modern country that left genocide out of its history, the Armenian diaspora focused on building new lives elsewhere.

The term genocide didn’t exist until Polish-Jewish lawyer Raphael Lemkin coined it in 1944, drawing in part from the crimes the Ottomans committed. In the 1960s, a wave of scholarship began unearthing evidence that showed Ottoman officials sought to build a country free of Armenians. The world took little notice.

A half-century later, Armenian terrorist organizations like the Justice Commandos of the Armenian Genocide, who claimed responsibility for the assassination of Orhan Gündüz in Somerville, used Turkey’s continued denial as fuel for their violent campaign. In lieu of justice, formal recognition of the genocide became a unifying cause within the Armenian-American diaspora. While 33 nations have formally recognized the events around 1915 as genocide, Turkey’s continued denial and the absence of formal recognition by the U.S. before last year had perpetuated feelings of a lingering injustice among many Armenian communities.

The killing of Orhan Gündüz remains part of a unique chapter in a century-old geopolitical struggle. It’s a chapter few choose to remember.

‘When they went to work, somebody usually died.’

After trying out a few smaller scale bombings in the U.S., the Justice Commandos began 1982 waging a campaign of violence across North America, mostly focused on Turkish diplomats. Their plans spanned both coasts and multiple targets in the Turkish diplomatic community. They sought more than acknowledgment — they wanted retribution.

“We will continue our struggle until all Armenian lands are returned to their rightful owners — the Armenians,” the Justice Commandos wrote in a 1982 communique sent to The Associated Press.

Orhan’s youngest son, Doğan, remembers the rising tension at home. “I knew we were in the midst of dangerous times,” he said.

On the morning of Jan. 28, 1982, two young men drove a 1977 Chevrolet Nova to the corner of Wilshire Boulevard and Comstock Avenue in Pasadena, California. They stood at opposite ends and waited for Kemal Arikan, Turkey’s consul general for Los Angeles, to pass by, just as he had a few days before when they had watched his movements.

The Turkish diplomat came into view and the men — referred to as Suspects No. 1 and 2 in FBI documents — each fired off multiple rounds. One of the men then approached a motionless Arikan and shot him at least two more times before running back to his car.

The Justice Commandos claimed responsibility for the Arikan hit. The killing had also appeared to follow the terrorist group’s typical modus operandi.

Of the 21 Turkish diplomats killed by the Justice Commandos between 1975 and 1982, 14 were attacked at traffic intersections. According to CIA documents released to MuckRock, the tactic earned scorn from the Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia, a rival, marxist Armenian terrorist group that favored explosives over shootings. They called the group’s tactics “cowardly hit-and-run assassinations.”

Recruits were mostly men in their late teens and early 20s, angered by Turkey’s continued denial of the genocide. They were willing to kill to avenge crimes committed against their grandparents. The FBI believed the group’s leadership came from an older generation of prominent Armenians who paired the radicalized teens with more seasoned 20-somethings experienced in armed conflict closer to their homeland.

“The Justice Commandos were known as a singularly effective group of assassins,” Wayne Gilbert, a former assistant director of the FBI’s Counter-Intelligence and Counter-Terrorism Division, told Reader’s Digest in 1986. “When they went to work, somebody usually died.”

FBI documents reveal their investigation of a California Armenian youth camp, where they believed the Justice Commandos had turned a rifle range into a proving ground for young operatives. At another Armenian youth camp, a 45-minute drive from Orhan’s shop in Cambridge, someone had stored 130 pounds of dynamite stolen from Michigan, according to FBI documents.

The CIA noted the Justice Commandos often followed a carefully plotted script, striking targets with barrages of bullets and then vanishing. In the Los Angeles shooting, one man escaped, but his partner hadn’t gotten far, exhibiting a sloppiness rare in the terrorist group’s ranks.

Police arrested him that night in the same car he had been driving since that morning’s killing.

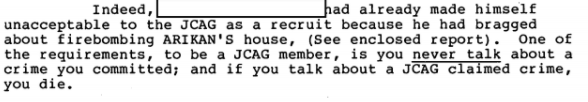

The man, 19-year-old Hampig “Harry” Sassounian, had found community among fellow Armenians after moving to the U.S. from Lebanon. And he became increasingly agitated by Turkey’s denial of the Armenian genocide. Two years earlier, his older brother, Harout Sassounian, had firebombed Arikan’s home. No one was injured. An FBI source told his handlers that the bombing was not only unsanctioned by the Justice Commandos, but that Harout had then been ruled out as a potential recruit based on his behavior.

https://embed.documentcloud.org/documents/21748078-11_kapikill87/annotations/210598**1**">View note

Despite his missteps, the younger brother had succeeded in making their last name — Sassounian — synonymous with Armenian terrorism. From his jail cell, he quickly became a cause célèbre, with Armenians footing his legal bills and pursuing efforts to free him.

The January Arikan assassination had raised the stakes in 1982. The Justice Commandos now posed a serious threat on U.S. soil. With the other suspect still at large, the terrorist group turned their eyes to Boston.

‘I want your life’

Orhan Gündüz was born in Istanbul and grew up in Emirgan, a neighborhood located on the European side of the city, along the Bosphorus. He graduated from a military academy in 1942, and enlisted in the Turkish Army, elevating to senior captain, before resigning in 1954. He immigrated to the U.S. in 1963 so his oldest son could attend college. He became a member of Boston’s consular corps, helping sort out bureaucratic issues for Turkish citizens, and was a founder of the Turkish-American Cultural Society, which hosts the Turkish Film Festival.

In Cambridge, Orhan worked closely with his wife, Meral, and they were well known to fellow Turkish expats. They had two sons, Ferdi and Doğan. Orhan, then 60, cut a charismatic figure. Known as Orhan-Bey, Turkish for “uncle,” friends described Orhan as an on-call helper and workaholic who wasn’t particularly politically-minded. He was known more for his “bear hugs” and lacked an “activist temperament,” according to his family and friends in Boston’s quiet diplomatic scene. One newspaper columnist for the Boston Globe described Orhan as “reassuring, cozy, around when needed.”

But after accepting his mostly ceremonial position as Boston’s honorary consul in 1971, Armenian protestors picketed outside Orhan’s Central Square shop. In the two years before his death, the protests and harassment had intensified.

“I knew things were going on and that there were death threat phone calls that we would get repeatedly,” his son, Doğan, remembers. “I was aware that a tragedy could happen.” Someone poured sugar in Orhan’s gas tank. The phone at his home rang off the hook with death threats from unknown callers.

Ten days after the Justice Commandos took responsibility for the assassination of the Turkish diplomat in Los Angeles, Orhan received yet another death threat. A woman called, asked for him and then said, “I want your life,” before hanging up.

Soon after, Orhan brought home a German Shepherd to patrol the family’s property in Nahant, a small peninsula town just north of Boston.

The family, however, remained steadfast. “We won’t leave for a bunch of fanatics,” his older son later told UPI. Doğan was more fearful.

“I remember thinking: ‘What if something happens to my dad? How will I, as a 14-year-old, take care of my mom? I will have to drop out of school. I will have to get a job.’ So all those thoughts were swirling in my brain,” Doğan recalled.

For months, it was unclear if the harassment would escalate. The murdered Los Angeles consul had traveled the world on behalf of Turkey as a diplomat. Orhan was a Boston local, helping out his fellow countrymen with passports. But there were warning signs.

Before leaving his shop the day it was bombed, Orhan had a “peculiar” exchange with a customer — described only as a woman wearing a gray skirt and matching jacket. After he had greeted her, she left abruptly. He then closed up for the day and headed home.

A few hours later, a car slowed to a crawl in front of Topkapi Imports. According to one witness, two men jumped out and placed a small box in the doorway. A few minutes later, it exploded.

The UPI office in New York received a phone call 30 minutes later. A tape recording of a female speaking “in a very low voice” said the Justice Commandos of the Armenian Genocide were responsible and issued a warning: “Pay attention.”

The only other words that could be made out: “apologize to the public” and “massacre.”

No one was hurt, but the storefront sustained significant damage. The impact blew the marble slab walls of the alcove entrance into fragments. The front windows of the giftshop, an adjacent business and several on the second floor above shattered. A “heavy pungent powder burn odor” lingered in the air after the blast.

Two days later, at 2:30 a.m., the phone rang at Boston Police Department headquarters. The caller claimed that a woman, described as a local stripper, was involved in the shop bombing and was bound for Phoenix on a Greyhound bus, carrying nine sticks of dynamite in her bag.

After months tracing the Justice Commandos’ footsteps, the race to catch them was on.

Read part 2: As Orhan Gündüz became a target, law enforcement agencies shrugged off responsibility to protect him.