After part-time diplomat and shopkeeper Orhan Gündüz was threatened by the Justice Commandos of the Armenian Genocide, law enforcement declined to provide direct protection as a pair of joggers waited for him along his usual route home. This is the second in a four-part series on the killing of Gündüz, a low-level Turkish diplomat living in the Boston area caught up in an international assassination ring. Read chapter 1, chapter 2 and chapter 4.

“It was an eye-opening moment,” recalled retired Somerville police officer Tom Macone, 68, on a chilly morning last April as he revisited the location of Turkish diplomat Orhan Gündüz’s murder. 40 years earlier, Gündüz’s white Ford LTD ended its unruly trajectory here after he was gunned down driving home. Now the house at the corner of Newton Street and Webster Avenue is condemned with boarded-up windows and large red X’s.

Macone arrived roughly 20 minutes after the shooting and was met by three fellow officers and a crowd of neighbors pooling around a crashed vehicle. The car, bearing Massachusetts Consular Corps registration plate No. 8, had crashed outside the house’s chain-link fence.

The windshield had several holes, and the driver’s side window was shattered. Inside the blood-spattered vehicle, the body of the driver was slumped over with several gunshot wounds.

“All I remember focusing on was the hood — I was mesmerized by the amount of rounds in it,” Macone said. “We did get a lot of shootings in Somerville at that point, but as soon as I got to the scene, I knew this was something very different,” he added.

Macone had been assigned Union Square to patrol, one of the tougher beats in a town nicknamed “Slummerville” by locals, due in part to infamous denizens such as the notorious Winter Hill Gang. “Crime-wise, it was pretty nasty,” said Macone.

But this killing immediately stood out.

“It was clear that it was a carefully planned hit. Whoever it was had taken their time with it,” said Macone. “This was of a much bigger magnitude than what we typically saw.”

The FBI documents and reporting from that day tell a story of chaos. One witness told the Boston Herald he heard the first popping sounds and turned around through a cloud of smoke to see something he could only describe to reporters as “really weird.” A young man in a jogging suit was standing as if in a fencing position, his right hand extended at the car as he fired, his left hand held high behind his back. From the vantage point of a nearby used car lot, it appeared to the witness that the gunman was jumping up and down as he pulled the trigger. “I couldn’t believe it. I said: They’re killing him,” the same witness told The Boston Globe.

A conflicted, chaotic scene

The married couple in the car directly behind Orhan’s had watched the scene unfold from five feet away. A “young lad” of 18 or 19 with “a kid look about him” had stood in Orhan’s path, “glared” as if to make an “obscene gesture,” but instead opened fire. As the car rolled to the left of Newton Street, the gunman moved with it.

Gliding to the driver’s side of the vehicle, he pulled out a larger gun and pointed it at Orhan. Once the bullets stopped and they saw the gunman flee, the husband called for help on the citizens band radio in his car. His wife left the car and walked over to investigate. Instead of finding Orhan in his pristine plaid sports jacket and tie, she found what she would describe to authorities as a “blood man.”

Many bystanders reported seeing the jogger flee in the direction of Dunkin’ Donuts at the bottom of Newton Street where it meets Union Square. According to Macone, a few of his fellow officers were eating inside the Dunkin’ within earshot of the gunfire. The distance from Orhan’s vehicle to the Dunkin’ Donuts was about 400 feet. The cafe itself is just across the square from the police station.

Two guns — a .357 magnum Ruger revolver and a 9 mm Browning semiautomatic pistol — were found at different locations near Orhan’s car. Part of a jogging suit and a pair of sunglasses worn by the jogger were found. Conflicting witness accounts also put another jogger — with a slightly different physical description— running in the opposite direction. Some said they saw a man with two guns; others, just one. There were multiple witnesses to the shooting and the immediate aftermath. The woman who had a “buzz on” from smoking pot and had recognized the jogger from the nearby Roosevelt Towers right before the shooting watched him flee by turning left down Emerson Street, right on Everett and then back onto Newton Street before disappearing into Union Square. Another believed they saw the jogger run a complete triangle around the block and run back up by Orhan’s car to peer inside before fleeing. It was as if the assailant had been everywhere and nowhere at once.

Somerville Police arrived within minutes, some coming from the Dunkin’ Donuts, according to Macone, others a block away from the headquarters. At 7 p.m., a male caller to UPI claimed the attack for the Justice Commandos of the Armenian Genocide (JCAG), the first of several calls made that evening crediting the group.

The SPD and surrounding neighbors had questions, but they wouldn’t get answers when the FBI arrived on the scene.

“When the Feds arrived they realized that it was chaos,” Macone said. Crowds of police, press and onlookers gathered around the car. “It was like herding cats,” Macone said, remembering police attempts to quell the crowds and close off streets.

The car, with the victim still inside, sat for two hours in the neighborhood before being towed across the square to the garage at police headquarters. Macone stood guard in the alley, shooing away reporters while colleagues processed vehicle for evidence.

The medical examiner found 13 bullets had been discharged, leaving indistinguishable entry and exit wounds. Orhan had been hit by at least nine bullets. The examiner removed one complete bullet from his shoulder and another from his chin, finding bullet fragments throughout his body.

The press played its own role in the chaos and confusion. Photos of Orhan’s bullet-riddled body made the front page of the Boston Herald and were sold to outlets nationwide, without concern for the active crime scene or the effect on the Gündüz family.

While UPI reported a pair of assassins, similar to the duo a witness reported earlier, most media focused on a single killer.

While there had only been one shooter, JCAG’s modus operandi of dispatching teams suggested the gunman hadn’t acted alone and, at the very least, had a handler. Investigators explored the possibility of a getaway driver. “From what I understood at the time, it was supposedly a hit team,” recalls Macone.

Macone and other Somerville police officers who worked the scene were interviewed by INTERPOL. “We were told to stand down,” recalls Macone. “Don’t go looking for some Somerville hoodlum or a Winter Hill guy. The Feds had it now.”

In the days following, the Somerville Police were kept out of the loop, so much so that when an abandoned car appeared one mile from the Gündüz crime scene in Union Square a few days later, the SPD did not notify the FBI.

The Kapikill Files

President Ronald Reagan branded the killing “a cowardly assassination,” saying: “The government and the people of Turkey are friends and we share with them the condemnation and the mourning for the counsel general.” He warned that “no quarter” would be given to the terrorists.

The broader Armenian-American community responded by condemning the assassination, though again situating the crime within the context of a violent history.

“The Armenian Assembly of America has stated repeatedly that it deplores the taking of any human life and the Turkish denial of the Armenian Genocide of 1915-23, in which 1.5 million men, women and children were murdered….The Armenian-American community looks to the Republic of Turkey to end this senseless spiral of denial and violence,” wrote Ross Vartian, director of Armenian Assembly of America, Washington D.C., in a letter published in The Boston Globe on May 17, 1982.

“Now for the cannon,” the strange phrase that a witness had heard the gunman shout, still lingered in the air, unexplained. Cannons had long played a symbolic role in the tumultuous history between Armenian and Turkish peoples. In 1915, during the defense of Van — a historic, Armenian cultural center in the mountains of Southeastern Anatolia — previously disarmed Armenians took up weapons and waged a resistance against the Ottoman forces accused of massacring villages and launching a siege of the city. Armenians captured several Ottoman cannons and also constructed an “Armenian Cannon” from melted-down pots, pans and everyday objects of the civilians involved.

It served as a largely symbolic weapon. For generations, the armed defense of Van by Armenians would stand at the crux of genocide denial arguments that falsely equated defense as Armenian instigation, an argument that came to be viewed by many historians as a calculated pretext for genocide.

In Reagan’s America, guns were available to anyone with cash. In what became known in the FBI’s files as the “Kapikill” investigation, the Bureau spent months tracking the weapons thrown into the bushes near Orhan’s car after partially restoring an obliterated serial number. Despite several pings across the country, none of the guns’ previous owners or sellers immediately led back to JCAG.

Return of the Rabbit

On May 10, the South Boston mom who had sold her 1976 VW Rabbit to a nervous young man with the phony-sounding name “Loosiciano” two weeks earlier got a surprising call when she returned from a trip to Florida. Somerville police informed her, as the last registered owner, that the car had been abandoned near a Holiday Inn and towed. Though she explained she had sold the car, the police told her it was her responsibility to retrieve it. A week later, on May 19, she paid the tow fine, and the car was released to her.

She immediately noticed that the rear driver’s side fender had a new dent in it, as if it had been bumped from behind in traffic. Inside the car were clothes, including a pair of royal blue track pants and a black “Members Only” jacket as well as a pair of sunglasses resembling those worn by Mr. Loosciano when he had purchased the car. The items of clothing smelled “so badly of body odor” that she washed them and also cleaned the car.

It wasn’t until hearing about the Gündüz murder from a friend and contacting her lawyer that she began to piece together that her car was involved. She called the Somerville Police, who hadn’t made the connection either. On May 25, a full two weeks after the car had been recovered, the FBI was contacted. Though much of the precious physical evidence had been destroyed, Adidas tracksuit pants found within visibly matched the already recovered Adidas jacket.

But the Rabbit’s owner did not recognize Mr. Loosciano’s face in the police sketches of the gunman. Investigators indicated the possibility that he may have played a different role involving the Rabbit other than shooter, though nothing was ruled out.

In addition to chasing the provenance of the two guns, the Bureau made one of several attempts at hypnotizing witnesses to tease out more information after connecting the Rabbit to the Gündüz scene via the missing half of the tracksuit. A Somerville Police Detective who had arrived early on the crime scene recalled seeing a vehicle matching the Rabbit’s description in the vicinity right after the shooting.

One of the hypnotized witnesses had been driving the vehicle two cars ahead of Orhan’s and recalled seeing “a dull, dark colored station wagon” directly behind her, in between her car and Orhan’s. The driver of the car directly in front of Orhan’s never came forward, another sign of possible involvement, according to the FBI.

Perhaps the Rabbit had been used to trap Orhan Gündüz in rush hour traffic or served as a getaway car, or both.

One of the drivers in the cars behind Orhan’s had mistakenly thought he was from out of town because he had slowed down to let traffic pass — uncharacteristic civility for a Boston driver.

From both coasts, JCAG attracted national attention. Legal proceedings in Hampig “Harry” Sassounian’s trial for the January 1982 assassination of Turkish Consul Kemal Arikan began in Los Angeles the same week of the killing. The FBI also received word from the State Department that Turkish officials had expressed “distress” after pleading for protection for Orhan in the wake of the March shop bombing. They were also requesting protection for diplomats along the East Coast. The next few months would see the FBI simultaneously investigating two assassinations while trying to get one step ahead of JCAG.

JCAG strikes again

Almost immediately, agents found many within the Boston Armenian community were wary. Orhan’s killing occurred barely a week after the FBI surveilled the April 24 commemoration, and the ARF Central Committee warned against being profiled and harassed by law enforcement.

“The agents usually begin by asking a few simple questions which you probably would not mind answering,” a May 12 communique states. “They have in the past, however, then quickly moved on to ask some of us questions about political organizations we belong to, about the activities of our friends, and have shown us pictures of legal pickets and demonstrations we have attended, asking us who the people are in the photographs.”

In Somerville, some began to fear for their safety. One witness dodged the FBI’s initial attempts to contact him, worried about JCAG reprisal against snitches.

Later a story appeared in the Boston Herald that stated a man claiming to be a witness to the Gündüz assassination was shot at along the tracks near Union Square months later. Turkish-American websites would later state that the witness who had given a description of the Orhan’s shooter used in the police sketch was later shot and hospitalized, reports that remain unconfirmed but contributed to the mystery surrounding it.

Contacted last year, two of the living witnesses named in newspapers in 1982 did not respond to multiple requests to provide comment and revisit the events surrounding the murder.

While the FBI’s files document many interactions that appear to be wild swings in the dark – such as asking church leaders if they know any terrorists – there are several Armenian community members who apparently risked their lives to provide information that led to the unraveling of JCAG’s broader plans.

Two months after the Gündüz hit, sources cooperating with the FBI’s Los Angeles office told agents that increased security for Turkish diplomats in Canada had delayed planned attacks. On April 8, 1982, Turkish Commercial Counselor in Ottawa, Kani Güngör, survived an attempt on his life. By July, sources were telling the FBI that the heightened awareness and security had “thwarted an assassination attempt.“

Whoever was providing this info, the Bureau noted, was deep within JCAG. The risks were high:

Despite the inside information, Turkish military attache Col. Atilla Altikat was gunned down at a stoplight in Ottawa on August 27, 1982. Canadian television aired a composite drawing made from witness interviews, which an airline worker noticed looked similar to a Jordanian man who was stopped just a few days before. The traveler had produced a ticket with an itinerary that showed a departure from John F. Kennedy Airport in New York City on August 28.

With an arrest warrant in-hand and two Ottawa witnesses in tow, Canadian authorities met the detained man at JFK. When a witness was unable to identify him, he was released.

The next day — acting on an asset’s tip — a Los Angeles FBI surveillance team photographed a party at the Adiss Golden Village Restaurant on Hollywood Boulevard. The source claimed that a group of JCAG members were celebrating the success of the Altikat hit. The Los Angeles office also said “rumors” had spread among the Armenian community that the Ottawa hitman had flown back to the city under a false name, wearing a wig and makeup.

Hopes that the person could be tracked down were dashed when a source said that those involved in killing Altikat had successfully been returned to Beirut, although a source said one operative was later killed after JCAG determined “he was a smart alec and had to be taken care of.”

While the FBI hunted assassins, it also deflected blame. Reports in the press frequently stated the FBI had declined to offer Orhan protection. “Standing guard is not our function,” FBI special agent Lawrence Gilligan told the New York Times on May 6, 1982.

FBI files show that within a week, the Turkish government’s request for diplomatic security from the State Department became more urgent. Sources in Los Angeles were also coming through with more information: another, bigger attack was coming. The FBI also identified the Altikat party attendees in Los Angeles – and began watching them closely.

Thwarting Fauxbom

As Turkish officials continued to plead with the State Department, the FBI learned that a new Turkish consulate was set to open in Philadelphia. Word came that the opening would be a prime opportunity for JCAG.

The FBI interviewed the person set to lead the consulate. Based in Greenwich, Connecticut, he told the FBI he had no identifying information on his business address and that he had reviewed security procedures in the wake of Orhan’s death. Elsewhere in the FBI files, he is named as Karnat Arbay, Honorary Consul General.

Soon the chatter the FBI picked up from Los Angeles-based sources became too much to let the consul go unprotected. Sources pointed to the first week in October as the most likely time for JCAG to plant a bomb at the new Philadelphia consulate. Arbay was placed under a 24-hour watch. The restaurant revelers were also being watched.

Just before noon on October 2, a Chevrolet Malibu with four unknown males was followed through Cambridge to Logan International Airport in Boston. Three of the men left the car for the terminal, and emerged two minutes later with another man holding only a small bag. After obtaining airline itineraries, the FBI determined the likely inbound flights their traveler had arrived on. No arrests were made.

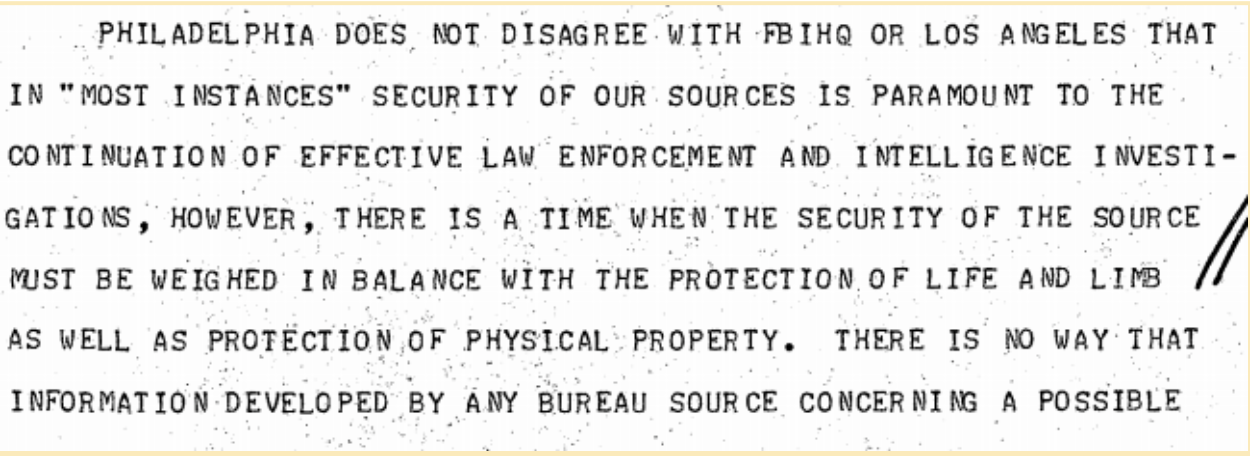

The consulate building was also placed on a 24-hour watch. The Bureau’s Los Angeles and Philadelphia offices had debated the merits of allowing the suspects to get as close to completing the action as possible against possibly alerting them too soon. The Los Angeles office warned sources could be killed if agents attempted to make arrests. Philadelphia responded that “there is a time when the security of the source must be weighed in the balance with the protection of life and limb as well as the protection of physical property.”

Given the location of the target, the Philadelphia office painted a stark picture: a bomb exploding at the consulate could kill or wound up to 3,000 people if it occurred during the day. The building housing the consulate was made entirely of glass, and sat near “one of the busiest and most heavily traveled roads in Philadelphia.”

By that estimate, the brewing plot could have been the deadliest bombing in U.S. history.

The Philadelphia office also worried that trying to stop the bomb from going off at the last moment could lead to a shootout:

The attack had been delayed following the surveillance of the October 2 activities. On October 21, however, a “highly suspected member of JCAG” was “busily scurrying” around Los Angeles buying bomb components.

On October 22, the FBI made its move when they learned their suspect had boarded a plane with explosives. In California, agents arrested Karnig Sarkissian, 29, of Anaheim; Viken Yacoubian, 19, of Glendale; Viken Hovsepian, 22, of Santa Monica; and Dirkan Berberian, 29, of Glendale.

A fifth suspect, Steven Dadaian, 20, of Canoga Park, California, was arrested at Boston’s Logan Airport. The bag he was supposed to pick up from Northwest Airlines Flight 208 held five sticks of dynamite, a detonator and a timer. The FBI noted the components were similar to those purchased by their surveilled suspect the day before.

Their capture made national headlines and kicked off what became two decades of legal wrangling related to what the FBI dubbed the “Fauxbom” plot.

The End of the Justice Commandos

Orhan Gündüz was the last known victim of the Justice Commandos in the United States. Following an attack in Lisbon, Portugal and Altikats’s death in Ottawa, JCAG claimed kills of Turkish diplomats in Bulgaria, Yugoslavia and Belgium before the group fractured.

The capture of the five young men that Armenian and Turkish advocacy organizations have since referred to as the “L.A. Five” also brought the FBI closer to Orhan’s suspected killer. In multiple documents within the Kapikill files, the FBI states they believed someone involved in Orhan’s killing was one of the defendants in the “Fauxbom” trial.

Although the South Boston woman who owned the Rabbit hadn’t recognized anyone in the initial police sketches of Orhan’s shooter, she eventually saw Mr. Loosciano again. This time his face appeared among the photos of the five Fauxbom defendants provided to her by the FBI.

A prison informant provided another crucial break in a case. The prisoner felt obligated to share a conversation he allegedly had with one of the Fauxbom defendants in a prison exercise yard. The informant wrote in a letter to the local U.S. Attorney that he told the Fauxbom defendant he had “gotten involved in several Anti-American movements when I was younger (which was a lie).”

This fellow prisoner claimed to be a “singer,” who made records about the genocide and “stated that he hated Turks and that he had been in Australia and Boston when ‘something’ happened to Turks in those areas.”

The informant “got the idea that [redacted] was bragging about having something to do with either injuring or killing a Turk or Turks in Australia and Boston but had no other knowledge as to any details of these events.” He also describes seeing “a sheepish grin.”

“Mr. U.S. Attorney,” the informant wrote, “it is my belief from what [redacted] shared about their cause that they are very dangerous individuals who will not stop at nothing enclouding [sic] murder to accomplish their goals.”

The singer, the informant added, did not seem worried about being in prison for long:

The FBI spent the next five years pursuing this and other leads to find those responsible for Orhan Gündüz’ death. The singer waited for freedom.

In the final chapter, the FBI confronts a suspect believed to be responsible for Orhan Gündüz’s killing. Documents reveal what they knew about the suspected killer and his accomplice, as well as the failed attempt to bring charges. Forty years later, two communities continue to grapple with the legacy of tragedy and the search for justice.