Read the first part here.

Currently weighing in at 200,000 pages, the Code of Federal Regulations is expansive. Packed within the goodies of administrative edicts is Title 5, one of 50, which regulates administrative personnel.

The so-called revolving door between the public and the private sectors is not special to the correctional industry, which is not well-known for perks like high wages and job appreciation commensurate with risk. And, so, there in Title 5 is Part 2637 - “Regulations Concerning Post Employment Conflict of Interest.”.

The Bureau of Prisons issues such opinions each year. A sample from 2014 shows a slice of the process.

An employee, maybe once involved in rewarding some contract, wants to get a job in the private sector. As long as they pass the process, they can take their skills to the private sector. Sometimes this is fine. Sometimes, like in the case of corrections, it can feel like a betrayal.

The private prison industry is booming and legal in most of the United States. Even states that don’t have an operational private prison on their land may have some authorizing legislation or decision on the books.

Corrections Corporation - Red

GEO Group - Blue

Management and Training Corporation - Green

These laws appeared during a staggering rise in prison populations. In 1989 alone, the population across states and the federal system increased by over 82,000 inmates. Over half of the states were operating at well-over 100 percent capacity. Nearly three-fourths of the states, plus the nation’s capital and two territories, were under consent decree or court order to deal with overcrowding at unconstitutional levels.

The various routes that each state took to enacting privatization laws are unique enough to deserve their own evaluation. But that fact alone suggests advantages that private sector corrections has over its government counterpart: a centralized cohesion in its mission and enough familiarity with local systems to adjust. Add to that the fact that at the federal level and across the states, standard ethics requirements do very little to prevent the private sector from swiping experienced employees, and the experiment with private prisons spits its lack of control right in the face of the scientific method.

Nonetheless, hundreds of contracts have been entered into across the country.

These contracts have often included a quota, a reasonable abstract business request but a common outrage in this context. They’ve also included bits about having appropriate American Correctional Association accreditation and cost-saving standards. But they don’t have real performance measures or challenges - as a tool as it is, it’s a waste. Rather than regularly demand rehabilitative measures or innovative education on some incentive-based reward system, they generally promote the status quo but cheaper. And then the government is legally bound to the low standards it has set, for itself and for its contractors.

All of which have left places vulnerable to private correctional firms turning the table on them, because, of course, it isn’t technically illegal for a business to exploit governmental inadequacy.

Other legal and constitutional issues have fallen into place for now.

Materials can be legally kept from the public, because private companies get that right. That’s standard practice.

Adjustments can, and have, been made to existing rules governing private security officers to allow otherwise inexperienced employees the ability to use force on inmates just as a public correctional officer would. That’s an easy fix.

And constitutional concerns would rely on demonstrable, systematic violation of rights to due process and standards generally afforded public prisoners. That’s hard to prove.

Further, ethics considerations explicitly state that particular post-employment exemptions can apply to those particularly suited for a private sector position. One would be hard pressed to say that someone with decades of correctional experience isn’t particularly well-qualified to help a company establish a competitor to that model.

So, that three Directors of the Federal Bureau of Prisons - early skeptic Norman Carlson, J. Michael Quinlan, and Harley Lappin - have gone on to lauded careers with major private prison operators, then, should come as no surprise. Throughout the criminal justice system, correctional professionals regularly move between the public and private sectors. It’s too easy, and not quite accurate, to criticize generally as nefarious.

Even still, both early supporters and opponents of private prisons agree on a few key issues. We have too many people in prison. Current rehabilitation programs aren’t working. And it remains exceptionally difficult to compare the effectiveness of the two.

In the current system, there is nothing necessarily inherently illegal about the use of private prisons. How are they even legal? In part, because — despite private-public turnover and speedily passed laws and court interpretations —

And future beneficiaries made a strong case for it.

And now here we are.

It’s a banal answer to a natural question. But it’s an important one.

Despite your feelings on the 2016 State of the Union generally, President Obama made at least one useful point.

“But democracy does require basic bonds of trust between its citizens. It doesn’t work if we think the people who disagree with us are all motivated by malice. It doesn’t work if we think that our political opponents are unpatriotic or trying to weaken America. Democracy grinds to a halt without a willingness to compromise, or when even basic facts are contested, or when we listen only to those who agree with us. Our public life withers when only the most extreme voices get all the attention. And most of all, democracy breaks down when the average person feels their voice doesn’t matter; that the system is rigged in favor of the rich or the powerful or some special interest.”

But that means if we want a better politics – and I’m addressing the American people now – if we want a better politics, it’s not enough just to change a congressman or change a senator or even change a President. We have to change the system to reflect our better selves.”

Private prisons are legal in the United States. The questions of how to make that happen were dealt with decades ago.

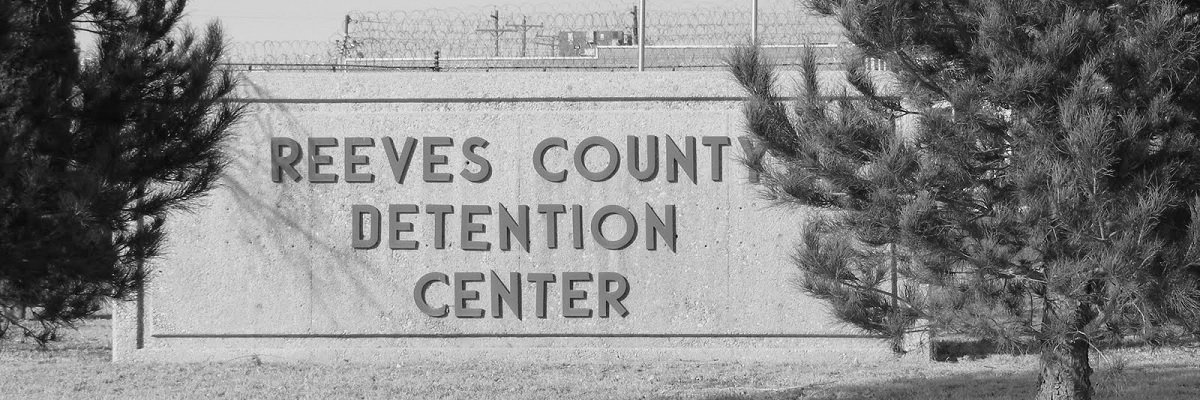

Image by Bill Bradford via Flickr and is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0