This week, the director of the US Marshals, Stacia Hylton, announced that she will step down within the year. As reported by The Hill on Tuesday, Director Hylton’s resignation follows increased scrutiny regarding allegations of fiscal mismanagement, cronyism and dubious surveillance practices.

But unlike Michele Leonhart, who resigned as director of the Drug Enforcement Administration last month after an awkward hearing over sexual misconduct by DEA agents, Director Hylton’s announcement did not ride the wake of any dramatic findings or even a hearing to review potential impropriety.

A handful of members of Congress — most vocally Senator Chuck Grassley of Idaho — have voiced concerns over USMS management and called for independent investigation by the Justice Department’s inspector general. No findings will be published for several months, at least, but the USMS director has now announced her resignation even before results from this new investigation are in.

As Director Hylton winds down her tenure, what few documents we have regarding surveillance practices by the US Marshals leave many questions unanswered.

The US Marshals Service has spent millions of dollars on StingRays and similar devices to track cell phones. Policy directives released by the agency confirm that its investigators — like their counterparts at the FBI and other law enforcement agencies — are instructed to go to lengths to keep details of cell phone trackers out of courtroom testimony and legal filings.

Over the past year, key details have emerged regarding deployment of cell site simulators by USMS investigators and deputy marshals. A Wall Street Journal investigation published last November uncovered a USMS program that uses airplanes outfitted with cell site simulators in nationwide fugitive manhunts.

The Justice Department refused to confirm or deny the program’s existence, but insisted the undertaking was legal.

Last summer, the US Marshals physically removed documents regarding StingRays used by one Florida police department. Two weeks later, the ACLU obtained emails indicating that the USMS asked the same agency to phrase court filings so as to obscure the role cell phone trackers played in an investigation.

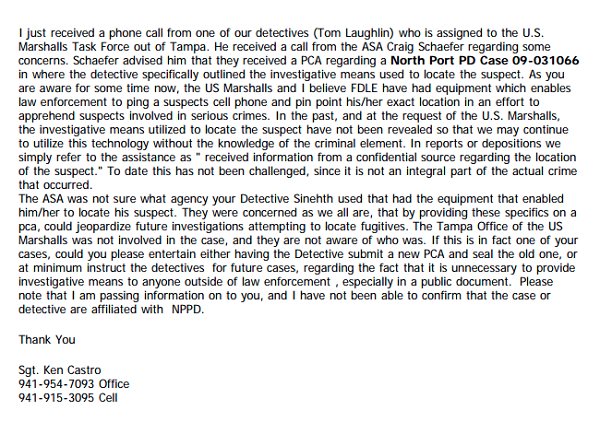

One April 2009 email chain details an agreement among the U.S. Marshals, an assistant state attorney and local police regarding the wording of probable cause affidavits (PCA) for a case where a StingRay was deployed to locate a suspect.

“In the past, and at the request of the U.S. Marshalls (sic),” Sgt. Ken Castro of the Sarasota Police Department wrote, “the investigative means utilized to locate the suspect have not been revealed so that we may continue to utilize this technology without the knowledge of the criminal element.”

“In reports or depositions,” the sergeant further explained, “we simply refer to the assistance as ‘received information from a confidential source regarding the location of the suspect.’”

Notably, the US Marshals replied it was unable to locate any communications with Sarasota police or its Florida regional task force regarding cell site simulators, despite considerable media coverage and litigation over the rapid document transfer. The Justice Department upheld the agency’s response upon appeal last August.

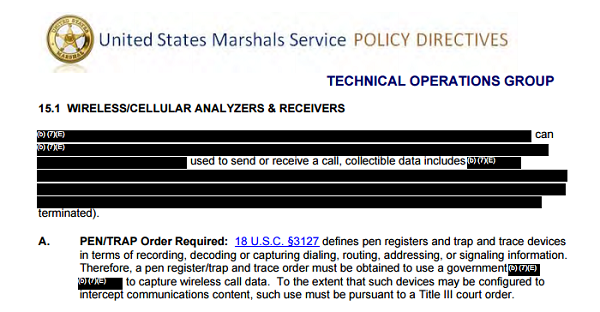

Forty-one pages of undated policy directives released in February by USMS in response to a Freedom of Information Act request include instructions to keep details of StingRays and similar surveillance tactics out of courtroom filings.

One of the broad directives indicates that the US Marshals must obtain a pen/trap order from a judge in order to capture “signaling information” from wireless devices. This information includes numbers dialed and the signals a cell phone exchanges with nearby network towers.

StingRays and similar cell phone tracking equipment use this information to triangulate a particular device’s location or record communications activity. To capture the content of communications, US Marshals must request a “Title III” or wiretap court order, which demands a higher evidentiary burden.

The FBI told legislators last year that its new StingRay policy requires agents to secure a warrant to deploy StingRays, rather than simply a pen/trap order, except under particular circumstances. The Justice Department also recently announced that it is reviewing policies across all of its components, including the US Marshals, when it comes to cell phone tracking. MuckRock is seeking documents related to both announcements.

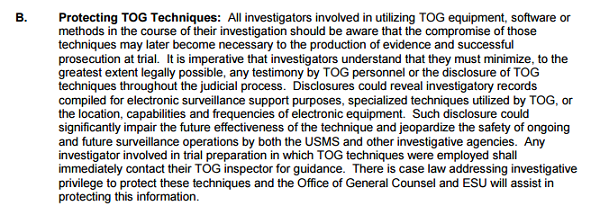

Another USMS directive — entitled “Security and Protection” — stresses that surveillance division agents must be kept off the stand, if possible, and disclosure of techniques minimized “throughout the judicial process.”

“It is imperative that investigators understand,” reads the directive in part, “that they must minimize, to the greatest extent legally possible, any testimony by [surveillance division] personnel or the disclosure of [surveillance division] techniques throughout the judicial process.”

“Such disclosure could significantly impair the future effectiveness of the technique and jeopardize the safety of ongoing and future surveillance operations by both the USMS and other investigative agencies.”

A spokesperson for the US Marshals indicated by email that the directive is current.

The USMS policy documents do not, however, define what constitutes the “greatest extent legally possible” or the limits of such efforts.

MuckRock will be monitoring these proceedings closely - please email all tips to info@muckrock.com.

This piece is part of the Spy in Your Pocket Project

Image by Shane T. McCoy via flickr and is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0