In the late ’90s, the shipbreaking yards of Texas, Virginia, and Maryland were dangerous, sometimes deadly places.

Workers without protective equipment plummeted to their deaths or toiled with torch cutters in the toxic holds of obsolete government ships.

In 1997, Will Englund and Gary Cohn exposed the hellish conditions in their Pulitzer-Prize winning series for the Baltimore Sun.

Their investigation set off a series of inquiries and reforms. Among the changes, the Department of Defense promised to tighten its bidding process to weed out unsavory shipbreaking companies.

But a decade and a half later, at least one company that scraps old Navy ships still falls short of bare-bones safety requirements, and faces light penalties when caught, according to OSHA reports MuckRock requested as part of the Pulitzer Project.

ESCO Marine, of Brownsville, Texas has been a prolific ship scrapper for the Navy in recent years. The company dismantled the USS Wabash, USS Roanoke, USS Holland, and USS Cimarron, among other vessels, in 2013.

Although ESCO didn’t star in Englund’s and Cohn’s original series, the shipbreaking and regulatory cultures of Brownsville did:

“A businessman gets left alone in Brownsville. It’s a long way across wide-open, flat scrubland to the rest of Texas. State environmental regulators don’t find their way down from Austin very often. The official in charge of PCB enforcement for the Environmental Protection Agency is based in Dallas, several hundred miles away, and went years without coming here. The two-man office of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, responsible for all of South Texas, is a three-hour drive away, in Corpus Christi.”

But recently, OSHA inspectors have turned their attention toward ESCO’s shipyard quite frequently.

In 2013, the agency issued the company 27 citations for violating safety standards, according to the investigation files.

The penalties ranged from a $1,215 fine for the company’s failure to monitor lead levels in the air to a $5,400 fine for allowing workers using cutting torches to work without eye protection. Welding visors became scratched after 15 days, one worker told inspectors, but the company would only replace them every 30 days.

The inspection reports document every citation issued to ESCO since 2010. Among the other violations:

In March 2012, an 80 ft. boom snapped off a crane lifting scrap from a ship deck. Although no workers were injured, an investigation found that operators had been writing down their concerns about the crane’s safety for months without the company taking any action. “This place is a hazard waiting to happen and kill someone,” an anonymous worker wrote to OSHA.

Several times in February and October 2013, inspectors observed ESCO employees working at precarious heights without any fall protection.

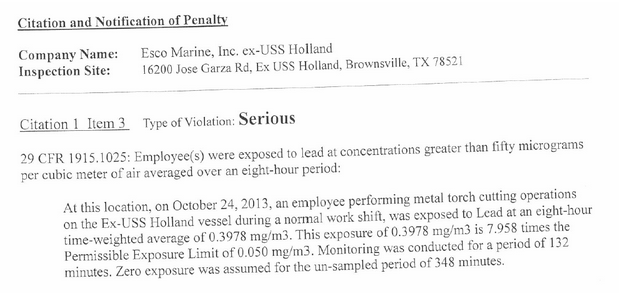

Air samples taken during an October 2013 inspection revealed that workers dismantling the USS Holland were exposed to eight times the acceptable amount of lead in the air and one-and-a-half times the acceptable amount of cadmium, a toxic metal.

But perhaps more alarming than the violations cited by OSHA, is the nonchalance with which the agency either withdrew its citations or reduced the fines.

In March 2011, another air test had determined an ESCO worker was exposed to nearly eight times the acceptable amount of lead.

ESCO subsequently agreed to monitor its employees for lead exposure on a quarterly basis. It did not follow through on that promise, however, and in February 2013 OSHA slapped the company with a $2,025 fine.

It turned out to be a very light slap.

Under the terms of an Expedited Informal Settlement Agreement, OSHA reduced that fine to $1,215 based on a 25 percent “Good Faith Reduction” and a 10 percent “History Reduction.”

OSHA determined that ESCO – which was caught exposing workers to dangerous levels of lead and then reneging on its promise to monitor lead levels – was entitled to that 35 percent fine reduction because the company had “good safety and health programs” and no instances of “serious, willful, repeat, or failure-to-abate” violations within the last five years.

But the cache of investigation files directly contradicts that reasoning.

For instance, lead exposure at that level is categorized as a “serious” offense in the files.

And three months after OSHA issued the settlement agreement to reduce ESCO’s fine by 35 percent, an OSHA inspector wrote damning grades for the company’s health and safety programs.

The inspector gave ESCO a grade of “inadequate” in all seven health and safety program categories, including safety training, health training, and preventive action taken.

Despite the multitude of citations the company racked up and its failure to fix problems, OSHA almost always entered an Expedited Informal Settlement Agreement with ESCO during the years covered in the investigative files.

Thanks to the agreements, ESCO rarely paid a penalty in full, as long as it agreed to take some corrective action.

Of the 27 individual violations OSHA cited ESCO for in 2013, the company only paid the full penalty on four of them.

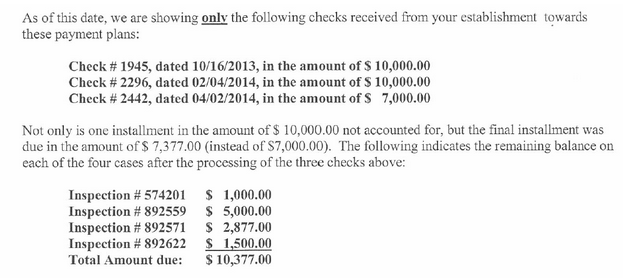

But even with those reductions, ESCO struggled to pay its bills.

As of May 2014, the last entry in the most recent investigation files, the company owed more than $10,000 in outstanding fines and had apparently stopped responding to the local OSHA office.

Read through the files yourself here.