Read Part 1 here

That morning, around 4 AM, I was finishing an interview with a Sicangu Lakota water protector named Phil Wright when he suddenly pointed at the sky: “Look, it’s one of those planes I was talking about! Look up! It doesn’t have its lights on but you can still see it against the stars!”

I didn’t see it yet, my eyes not as sharp, but it was low enough so as it passed over us, and I heard the hum of its engines. I could just make it out against the clear night sky. The hairs on the back of my neck pricked up. I tried snapping a picture with my phone, but it was perfectly camouflaged in inky blackness. It is illegal for a civilian or commercial plane to fly with its lights off.

My sources all described these flybys as happening early in the morning, or later at night. While I can’t say for sure what that plane was, it felt like long odds that a small Cessna would fly low over a very small Reservation such as Lower Brule, directly over a protest camp, by accident. Certainly, as protesters plan their own resistance to the KXL, the government and the oil companies are watching them, studying them, very closely.

This also brings up something that was possibly the most troubling aspect of reporting out there. Every source, including a Tribal Chairman, wanted to discuss what has been termed the “DAPL Cough,” which manifests itself in a violent cough with a yellow-green phlegm, and in some cases, blood. Many reported having the symptoms up to three months after the Standing Rock protests ended, and many, if not all, believed the planes and helicopters were the cause. Some even reported having seen a light mist falling from the aircraft, or feeling an odd film on their skin. This of course is wholly unverifiable. But given the systematic and often violent oppression against their people by the U.S. government, to them the idea of being sprayed with a chemical agent is not farfetched. As Miengun Pamp, an Ojibwe water protector explained, “there were medical teams, we were eating healthier than most people do in our country, there was just no reason for all of our people to get sick like that and be in such rough shape.”

Which brings me to one of the often unspoken side-effects of counterinsurgency being waged at home: Paranoia runs rampant. It turns out that incessantly flying Cessnas and helicopters over a camp of peaceful protesters will produce strong feeling of persecution, something a young Lakota man named Iktomi spoke to me about. Whether or not the DAPL Cough was natural or caused by an agent, or even by prolonged tear gas or pepper spray exposure, the levels of persecution and law enforcement activity was enough to make that fear run deep. Pamp informed me that rather than post about the flybys on social media, they refrained because riling the camp up was the intended response. When they did post once about a flyby, Pamp told me “a lot of other camps started commenting, ‘oh we saw that too! We had a BlackHawk helicopter fly over, we had troop carriers come through. What they want is for us to freak out and call for backup. It would be so much easier for them anyway if we were all in one place.”

An Ihanktonwan Dakota water protector named Iktomi told me this concerning PTSD and paranoia,

“The smallest dab of paranoia is needed. When they sent that big Chinook military helicopter over us, I thought they were trying to put more of that paranoia in us. But when you have the right amount you can function right, but when you have too much paranoia, you blow things out of proportion. That helicopter, they wanted it to provoke us to call in more people. They are slowly probing us. When you were at camp you had a purpose, and that displacement aspect of the PTSD was, suddenly after camp that purpose was gone. it’s like you have guys coming back from overseas right, and they feel like they don’t know what to do, they have these skills they need to use, and they were protecting people. The water protectors suffering mentally, they are looking for a fight, but they don’t realize that now the fight is within themselves. It’s a spiritual fight. When you were at camp you had a purpose, and that displacement was, suddenly after camp that purpose was gone.”

I spent the next day there doing more interviews, two with former police officers Louis GrassRope of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe which is predominantly Sicangu Lakota, and Norman Redwing also Lakota and who hails from the South Dakota portion of the Standing Rock Reservation. Both agreed that behavior by law enforcement at Standing Rock was dangerous at times, particularly the role of riot police. Redwing previously worked as military police before becoming a BIA officer, and was present as crowd control at a race riot in Germany. He had this to say:

“The things I witnessed at Standing Rock … I counted at least eight civil rights violations. And I witnessed that when those things would happen, the National Guard would kind of back off, but they were witnessing it. If I was back as an MP and I had done some of the things I saw at Standing Rock, I would for sure be in military prison.”

When I asked him to list some of the violations he witnessed, here’s what he said:

“Well, the big one is the use of force, especially when the barricade went up. Why were they even crossing the barricade? Then there’s cell phone jamming, preventing potentially crisis calls from being made. And I actually saw officers setting out rubber bullets in the snow to freeze, and then loading them. I actually watched that. And those will do work [laughs]. They can break through. And they can be lethal. I’ve seen them shatter plastic.”

That night I headed back into North Dakota, staying the night at Prairie Knights Casino on the Standing Rock Reservation. There I experienced both friendliness, and wariness, a confusing combination. A bartender first asked me what I was doing so far from home. While eating a bison burger, I explained I was a reporter interviewing water protectors. She offered to try to get me into contact with her brother. I gave her my contact information, but nothing came of it. Next, a local man from the town Cannonball on the Reservation came up to me. His name was Allen, and was a former police officer as well. Maybe five or six times he asked me “what do you want to know,” as if I was not who I said I was, or was not representing my story correctly. Later, when he became aware I really was a reporter covering the issue, he offered to meet up with me later on the next day.

I had more driving to do the next day, and so I’d have to settle for a phone interview with him. Before ending our conversation for the night, he explained to me “we have been screwed over so many times on this story. I apologize for coming up to you like that, I didn’t mean to scare you or anything, but I just wanted to make sure you were for real.”

The encounter stuck in my mind as an example of the caution exhibited on the Standing Rock Reservation when speaking on these issues. On my first trip, I was told there was no speaking about the protest at all in the casino. It has opened up somewhat, but when anyone comes around telling people they are a reporter, you can see the guards go up.

From Standing Rock, I traveled north to meet with Mashugashon Camp, a mother and water protector living on the Fort Berthold Reservation. While she is Lakota, Ponca, and Hopi, and raised mostly Lakota, she lives on a Mandan, Arikara, Hidatsa Reservation. Fort Berthold is sometimes known as the Three Affiliated Tribes Reservation. I will forever be grateful to her as a host who fed me well, took me around the Reservation, and offered hours of her time to talk about seemingly everything - the treatment of water protectors, the bruises she saw on her brothers when they were returning from the front lines at Standing Rock, the regional racism in the Dakotas, tribal corruption, and environmental degradation. And most painfully, the destruction of sacred artifacts by police, on the last day of the camp. She was beyond gracious, feeding me homemade fry bread and soup and talking until 11 at night.

Before going any further, let me explain where Fort Berthold is exactly in North Dakota - along the banks of the beautiful and vast Lake Sakakawea, Fort Berthold lies in the Bakken region of the state. And the Bakken is North Dakota oil country. The highway leading onto the Reservation is peppered with oil derricks seemingly every half mile, with stacks leading up from the ground blazing with fire, spreading their poisonous fumes throughout the Reservation. As you get closer to New Town, the derricks become even more numerous. Industrial buildings loom over the town, and the groaning and beeping of oil tankers fill the air. It is in many ways the belly of a very dangerous beast: the black snake, triggering environmental collapse on a global and local scale. This is of course why I was there - the Dakota Access Pipeline, which water protectors struggled against with such determination, leads directly here. This is where the oil flows from.

Camp explained to me that when an oil boom occurs, like is currently happening on Fort Berthold, it is not simply the cancerous, disease causing chemicals that comes with it that pose a threat. With the oil workers, more often than not, comes crime. Drugs, prostitution, kidnappings. Native women go missing at an astonishing, tragic rate. One out of every three Native women report being sexually assaulted. 86% of the time, it is a non-Native man who is the perpetrator. She showed me Facebook groups dedicated to nothing but posting, every day, the women who have vanished. Fort Berthold claims its fair share of these. A Reservation thrown into chaos by an industry that seems to care very little about whether they live or die.

From Fort Berthold, I drove south to the Cheyenne River Reservation. Or thought I was. Halfway there, I discovered that due to the powwow happening in Eagle Butte on the Cheyenne River Reservation, the local motel had no vacancies - a first for me on my travels in the Dakotas. I stayed in Faith, South Dakota for the night, and in the morning met up with Cody Hall in Eagle Butte. Outside of his home, we talked among other things, his lacrosse program for Lakota youth from the Reservation. Hall has done truly phenomenal work, with very little resources. He has outfitted his team, 7 Flames Lacrosse, with cleats, sticks, anything they might need he works to provide. He works with colleges like the University of Virginia on potential scholarships for his athletes. And he provides getaways, a positive outlook, and guidance for his team.

Hall is an inspirational man, but to anyone who meets him face to face, it is abundantly clear he is not guilty of leading the entire protest movement, as some in government and TigerSwan have charged. Just to see him laugh when asked the question is almost proof enough. Yet that makes it all the more chilling to hear him say, “knowing how big a target I was, just from being the go-to media guy early on at Standing Rock, why would I want to go through anything like that again?”

Due to the constant surveillance he was experiencing throughout the spring and summer, Hall has had to stop his most treasured activity, running. He has panic attacks now. The thoughts about what he saw come back worst at night. “It’s affected my sleep pattern,” he told me. He struggles to catch his breath. “My head was spinning I was hot, I couldn’t breathe, I came outside here, I tried taking deep breaths but it just enhanced it more.” They have continued occurring.

PTSD among water protectors runs the gamut from just feeling out of place after months of purpose at the Oceti Sakowin camp, to those like Hall. This surveillance affected his daily life, while the brutality he witnessed haunts his nights. Hall is a family man and a youth leader, but he is no mastermind behind the protest, and will proudly tell you so. He is a self described ikce wicasa, Lakota for common man. He made sure I noted that at least three water protectors have committed suicide. One he knew personally, Justin King. When Hall went to his local spiritual healer, the man told him “there are others, Cody.”

I took in the spectacular powwow Grand Entry, and decided since I had to head back north to Bismarck later that night to catch a flight the next day, I should probably keep doing my job. I found what is called the Cheyenne River Honorary Water Protector Camp, a camp for displaced water protectors. I did not record there, as an elder and grandmother was present. I heard yet more details about the law enforcement response at Standing Rock. Lasting nausea and headaches, whether from the tear gas, pepper spray, or LRAD’s (long range acoustical devices), which caused water protectors head splitting headaches and caused many to vomit. This was not the only camp I heard LRAD stories from. A Lakota elder broke down into tears when discussing her PTSD, and her struggles finding employment since Standing Rock. But there was also so much pride. For them, Standing Rock was the beginning of awakening of consciousness in Native communities. To rise up and do something about the conditions in their communities.

In my larger pieces which will be published sometime this winter, I will explore more thoroughly these interviews and places which I discussed above. There is so much I was not able to discuss in this piece. It is just so much. But where does my reporting go from here? Well, my email, phone, and DMs are always open to water protectors or protesters from other communities who have experienced similar violence and persecution. But I would also like to speak to surveillance experts, PTSD experts, experts on tear gas and pepper spray and the effects of prolonged exposure. I would like to speak to professionals about the DAPL Cough.

For me, as a journalist, what haunts me the most about my trip out to the Dakotas is not necessarily even the stories of heinous violence, racism, and cultural destruction at the protests. No, as awful as those stories are, what haunts me is the background to all this. In this lonely region of the country, which receives the least amount of coverage and travel, there are so many stories to tell. There is so much work to be done. I will continue to report on Reservations and Indigenous issues. But, to bring all the beauty of the communities, the organizing, the fights to save culture, language, people, and environment, and yes, also the horror, in these regions to light would be impossible even if I spent an entire career doing it. I look forward to facing those challenges.

Thanks again to a generous grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism for making this reporting possible.

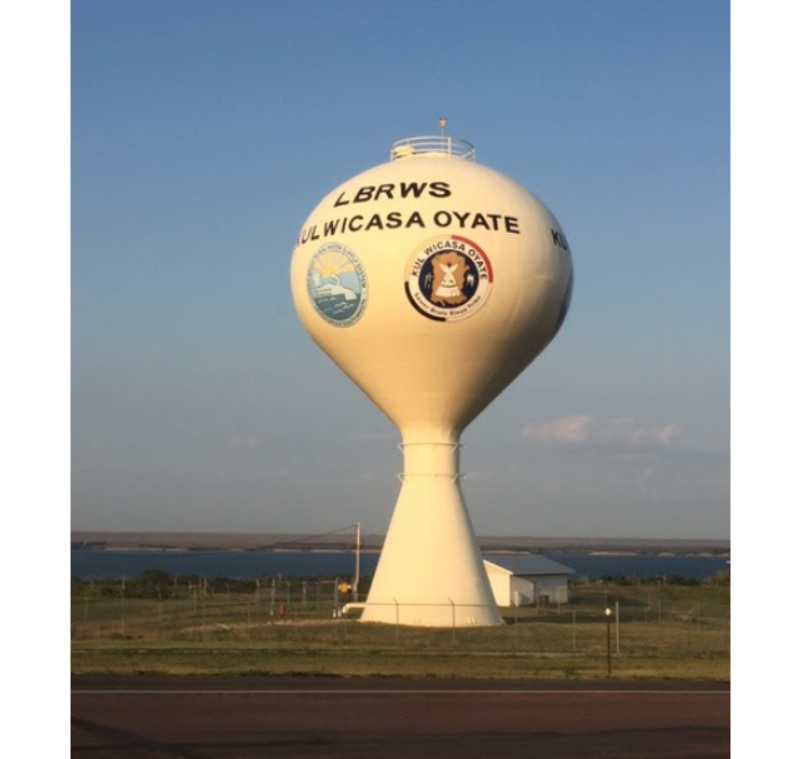

Image via Curtis Waltman