Labor organizer, Californian congressman, and mayor of San Francisco John Francis “Jack” Shelley is typically cited among the most prominent figures on J. Edgar Hoover’s “Emergency Detention” list of “subversives” that were to be arrested if war with the Soviet Union became “inevitable.” However, as Shelley’s FBI file shows, being marked as a potential threat to the country didn’t stop Hoover and Shelly from enjoying a cordial, if not down downright friendly, relationship during the latter’s time on the Hill.

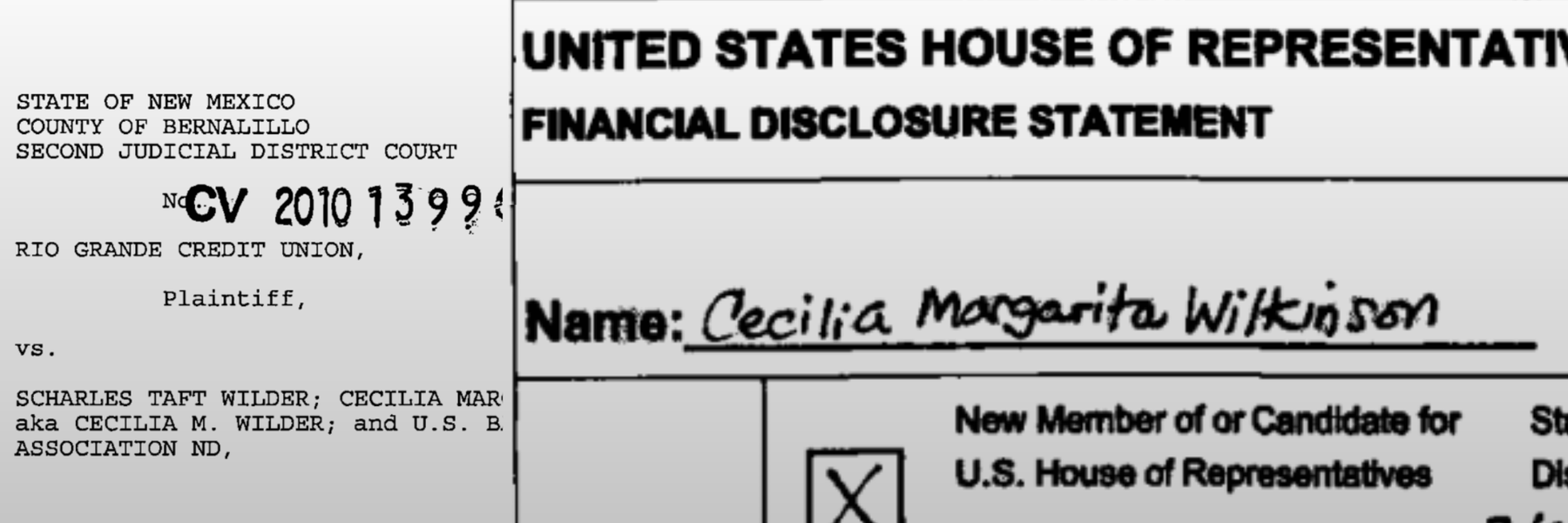

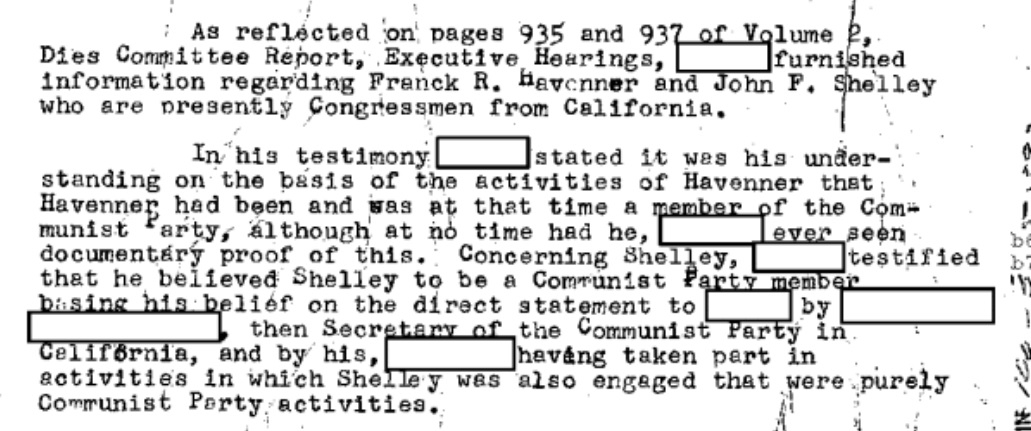

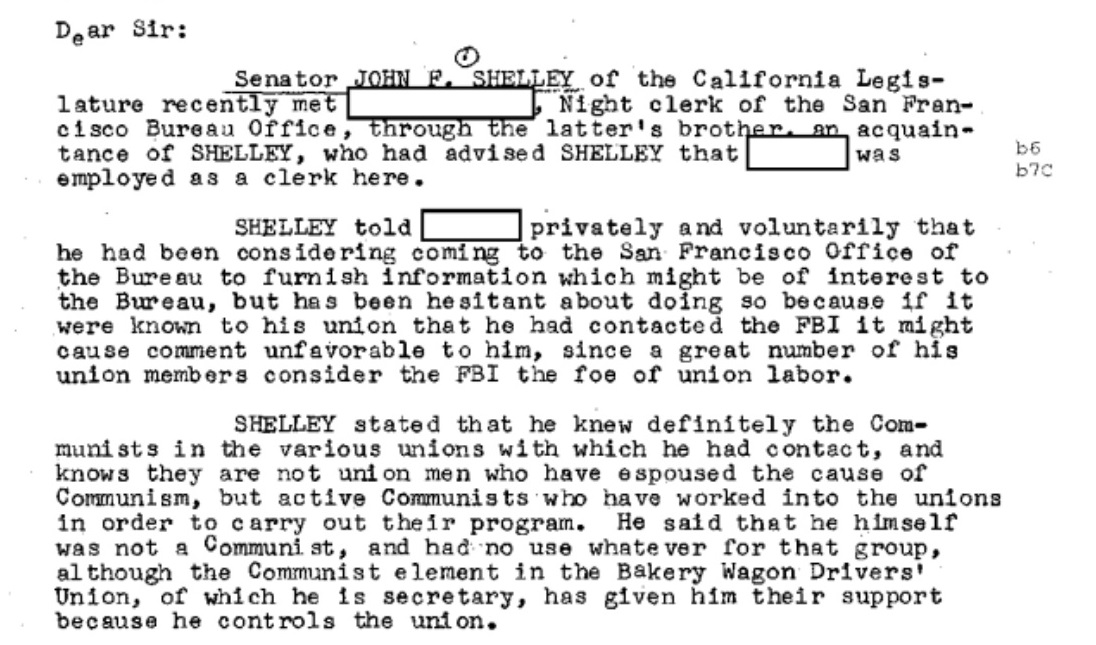

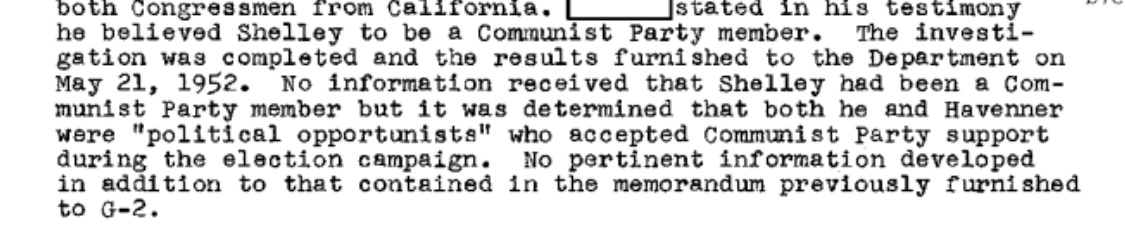

Even leaving aside the “secret detention order” thing for a moment, the relationship between the two didn’t exactly have a promising start. Shelley first shows up in the Bureau’s files as part of a perjury investigation into a Justice Department informant who had fingered both Shelley and fellow California congressman Franck R. Havenner as card-carrying communists.

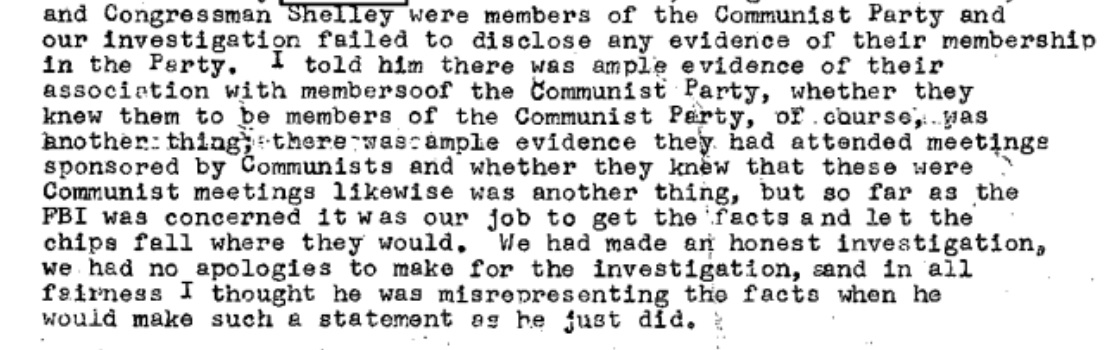

Havenner and Shelley both vehemently denied those charges, and understandably, the exchange got heated. At one point, the FBI agent in charge of the investigation rather testily reminded the two that while they might not be members of the party themselves, they had enough association with them to warrant suspicion as fellow travelers.

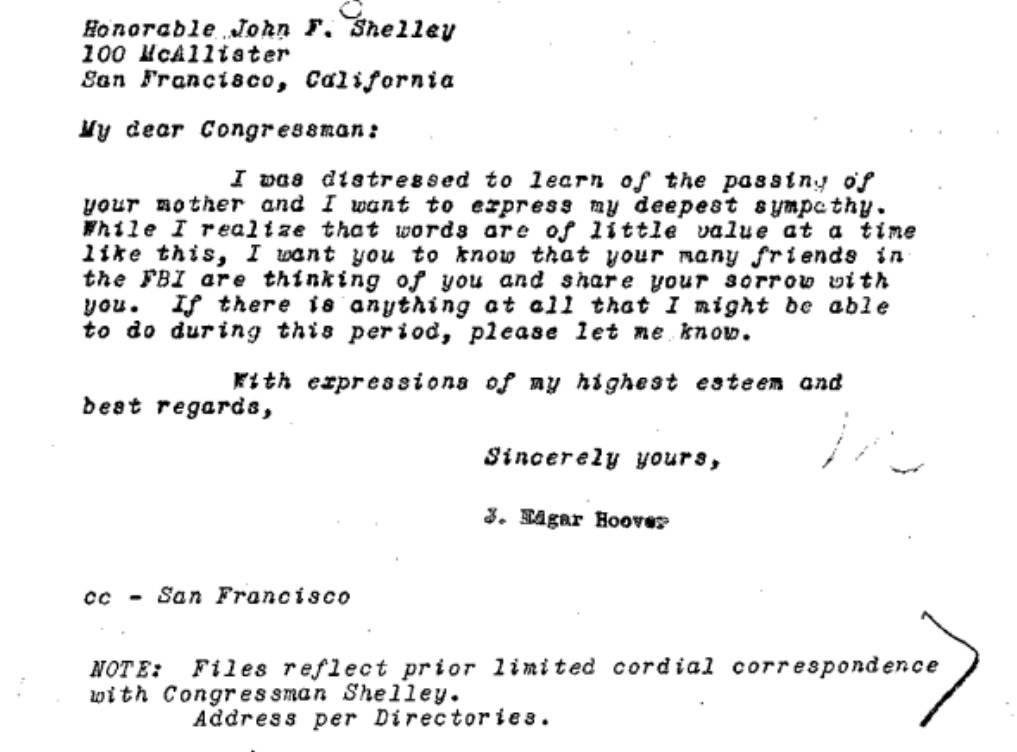

Then, a few months into the investigation, Shelley’s mother died. Hoover, a noted mother-lover himself, wrote a personal note to Shelley (which the file notes the Bureau had had “limited cordial correspondence with prior) expressing his sympathies.

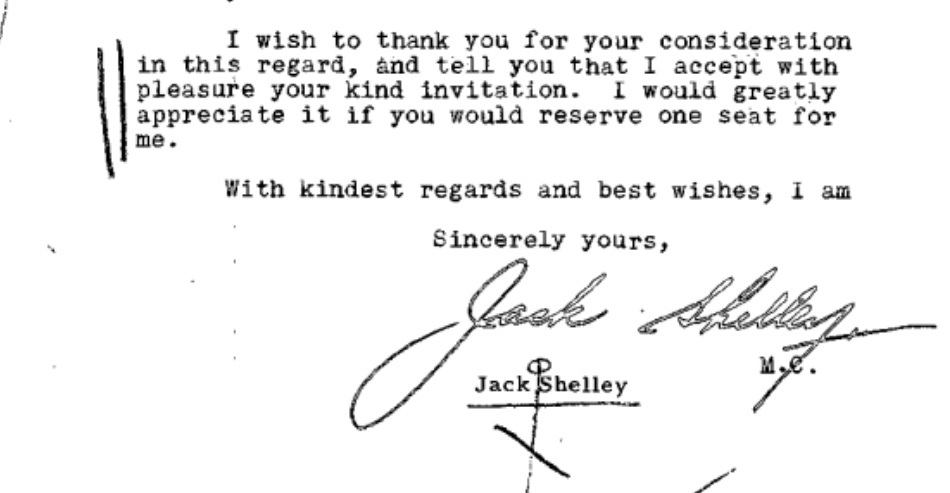

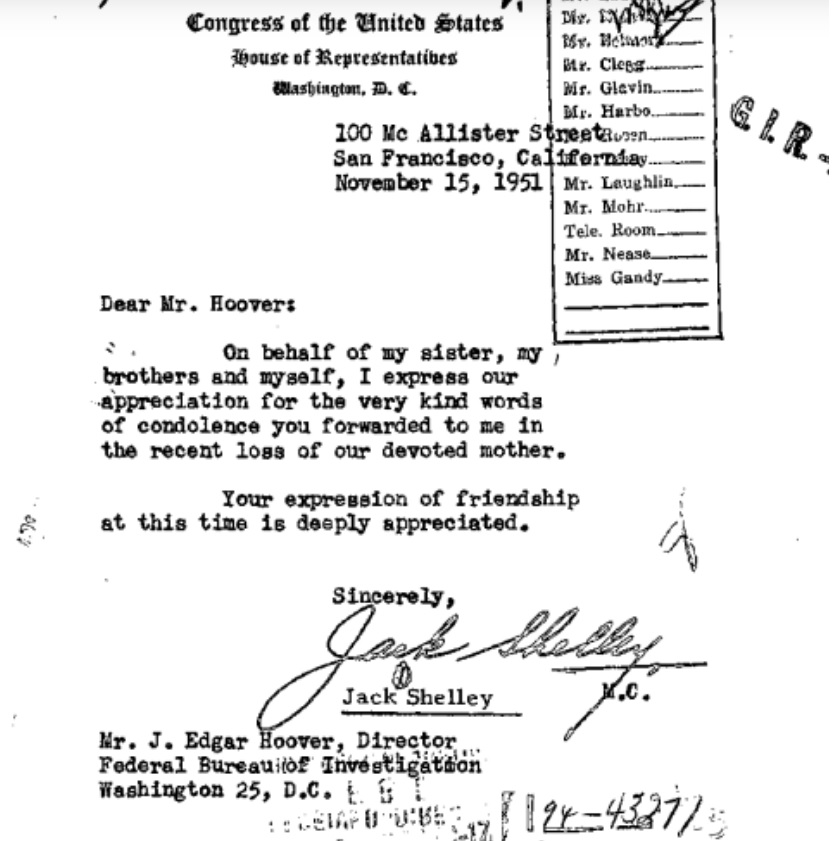

In response, Shelley wrote to thank Hoover …

and that, as they say, was the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

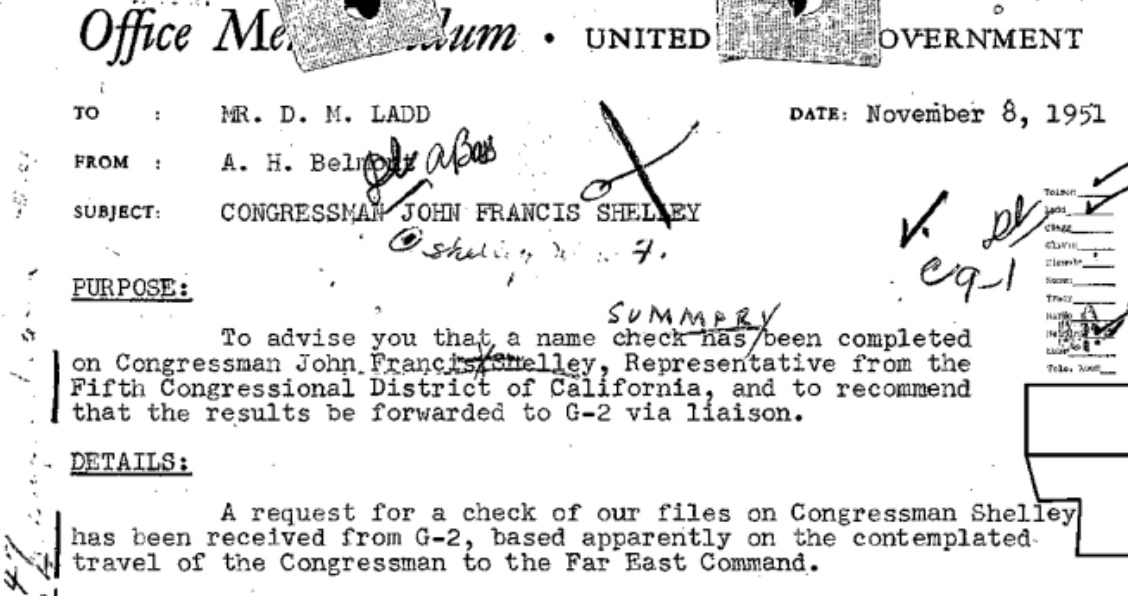

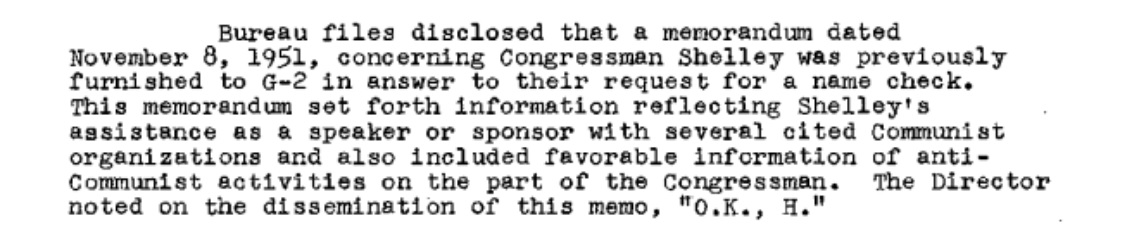

Between those two letters, the Bureau had received a request for a background check on Shelley from the Army, ahead of Shelley’s visit to the Far East Command in Japan.

Although the Bureau noted that Shelley had rubbed elbows with a few commies back in his labor days, they ultimately gave him a generally clean bill of health. Shelley was no Red.

So what had happened to change the Hoover’s view of Shelley from the enemy within to a bonafide American? Was it really so simple as a Batman v Superman-esque reminder that they both had mothers?

Not exactly. For starters, earlier that year, Shelley had approached the Bureau about potentially informing on communist infiltration of the labor movement.

That, combined with the findings of the perjury investigation, had led to the Bureau’s conclusion that Shelley was a “political opportunity.”

And while Hoover could never conscience a communist, a political opportunist is another thing entirely. Hoover could work with a political opportunist.

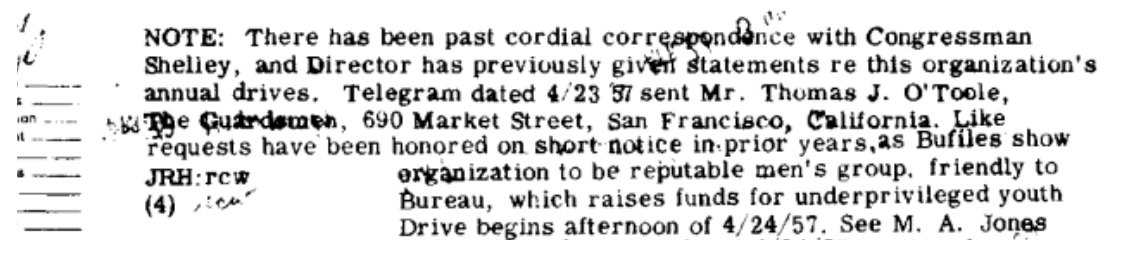

Following Shelley’s reelection, their relationship continued to improve, with Hoover a frequent guest speaker at the youth organizations that Shelley was involved in.

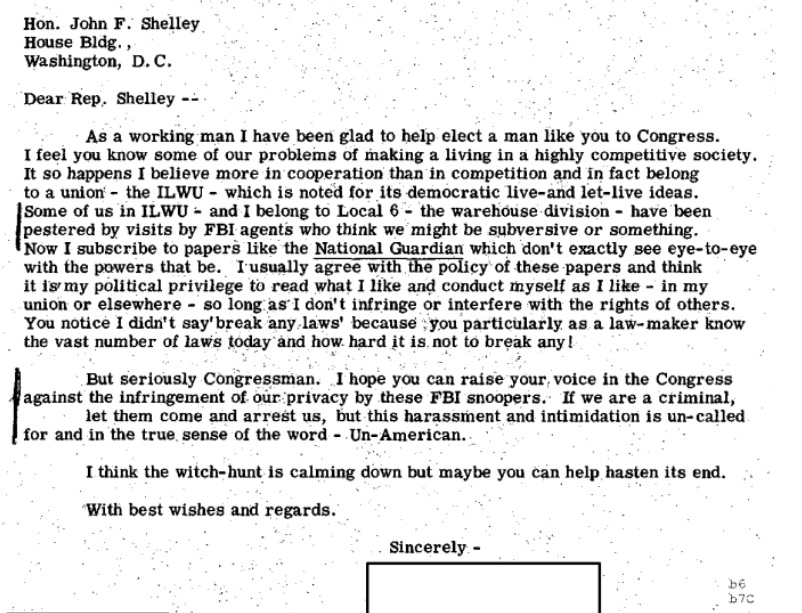

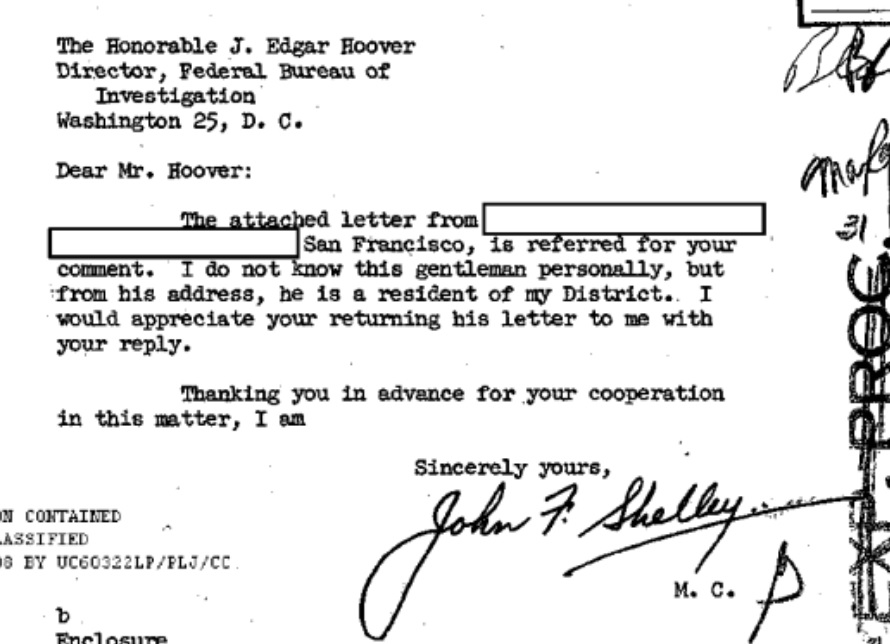

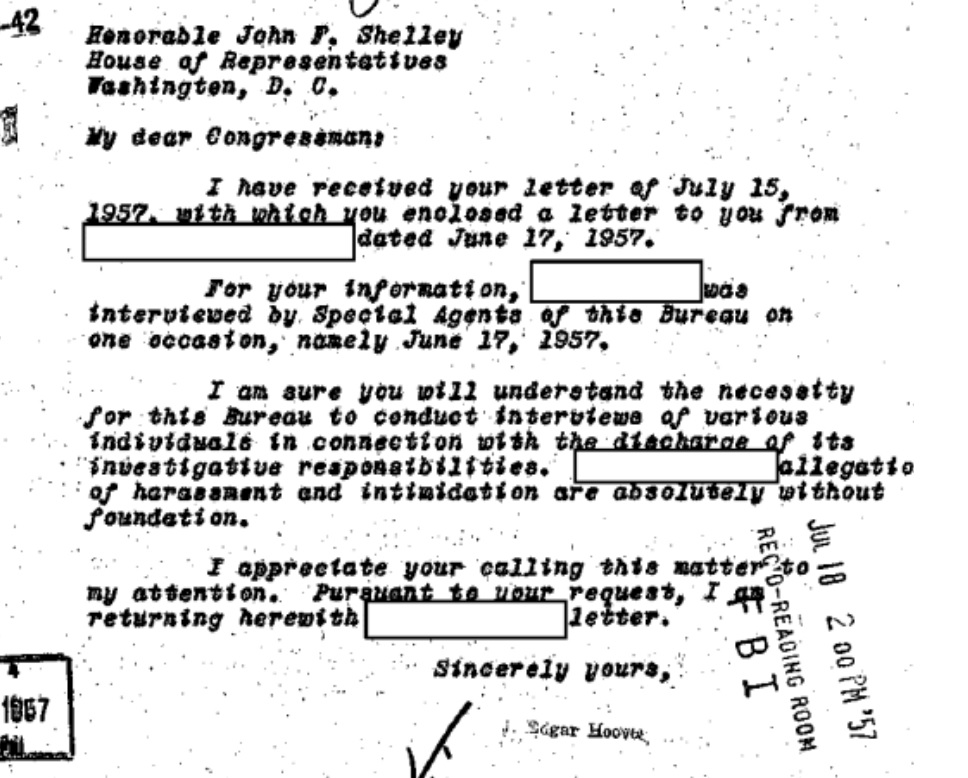

Their personal relationship was a factor when Shelley received a letter from a constituent urging him, as a fellow union man, to put an end to the Bureau’s “witch-hunt” in the labor movement …

which Shelley immediately forwarded on to Hoover himself.

The Bureau checked its files, determined that the man who wrote the letter was a deviant with an “inadequate personality,” and Hoover wrote back to Shelley, assuring him that the whole thing was being blown out of proportion.

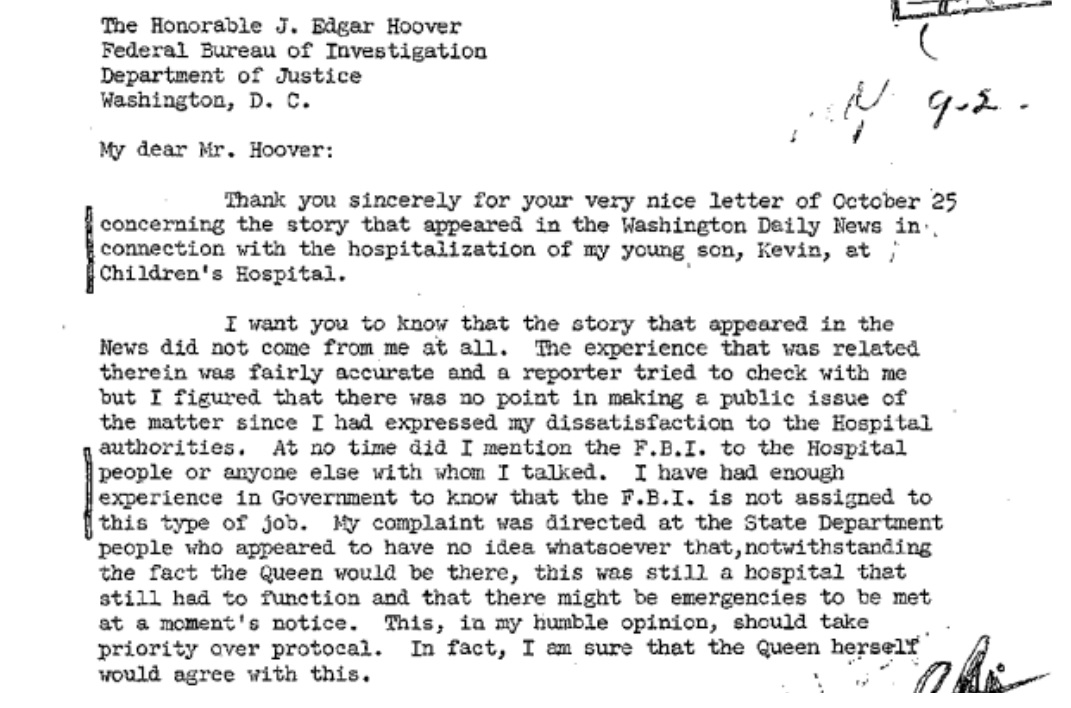

The closest thing to a snag between the two was a brief run-in with the mid-century equivalent of #fakenews. During Queen Elizabeth’s visit to the U.S. in 1957, Shelley was unable to visit his son at a hospital Her Royal Highness was visiting. The tabloids reported Shelley railing against the “FBI, Secret Service, Scotland Yard, and the State Department” …

which Shelley insisted had been a misquote. He had just been mad about the State Department.

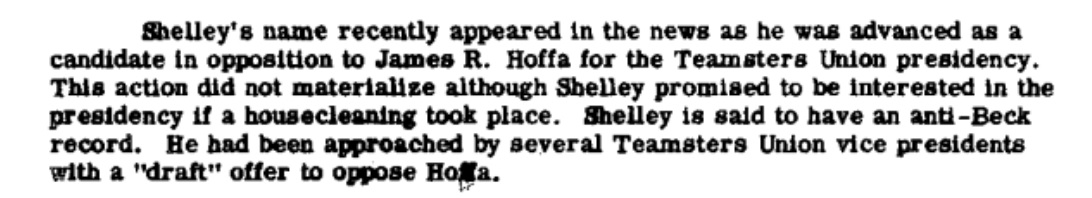

Other than that minor blip, it was a non-stop lovefest from here on out, with the Bureau noting approvingly that Shelley was a potential challenger to Jimmy Hoffa …

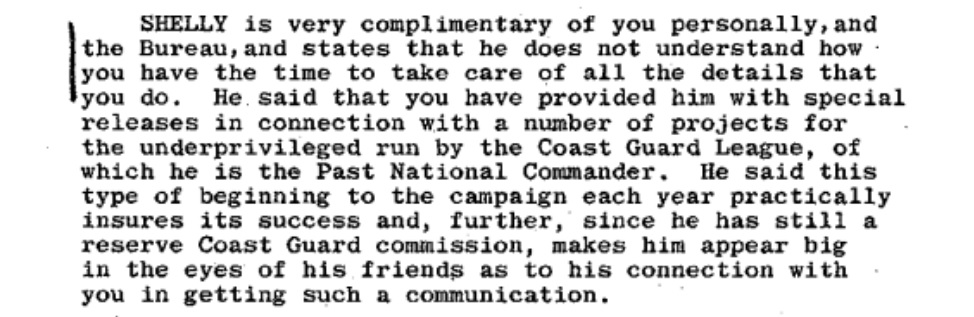

and Shelley bragging about how cool everyone thinks he is because he had the director on speed dial.

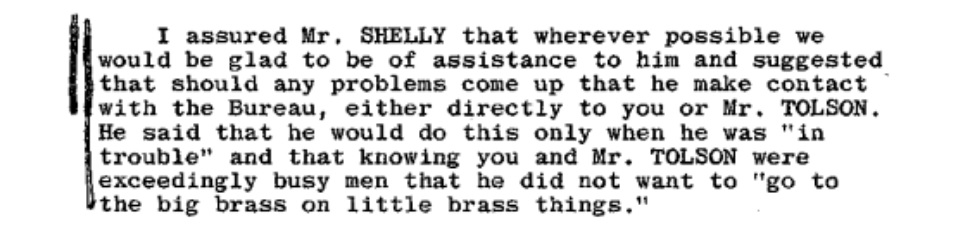

That last part wasn’t exactly an exaggeration. Shelley, who at this point had “grown up” and abandoned his earlier delusions about communism, was given not one, but two direct lines to the Bureau if he could be of assistance with their investigation into the labor movement.

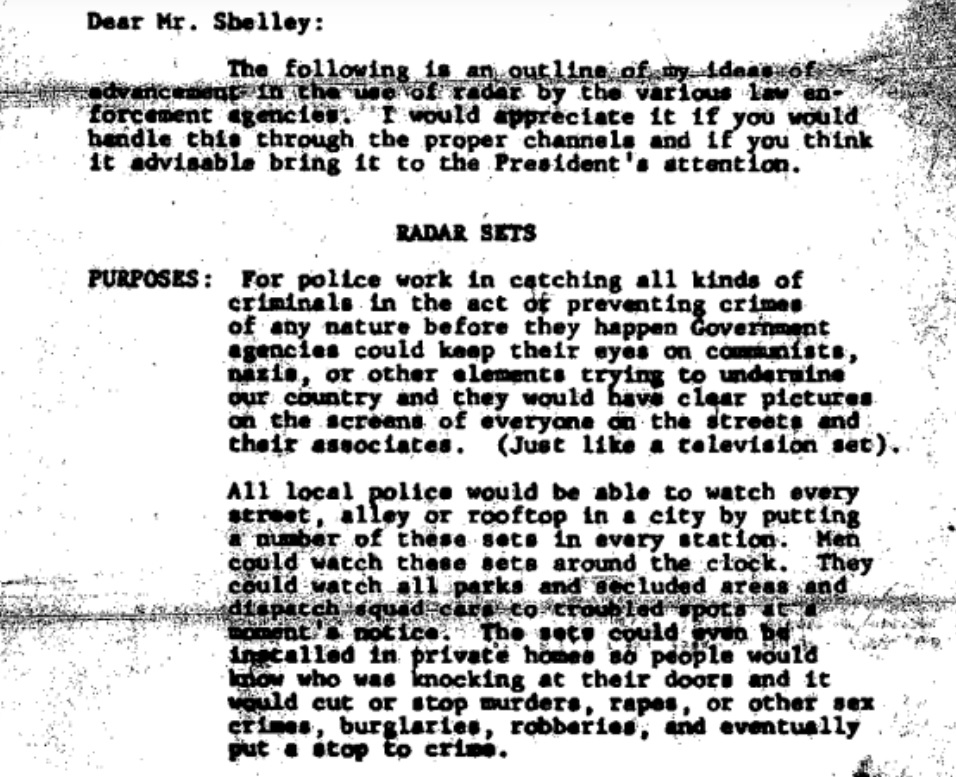

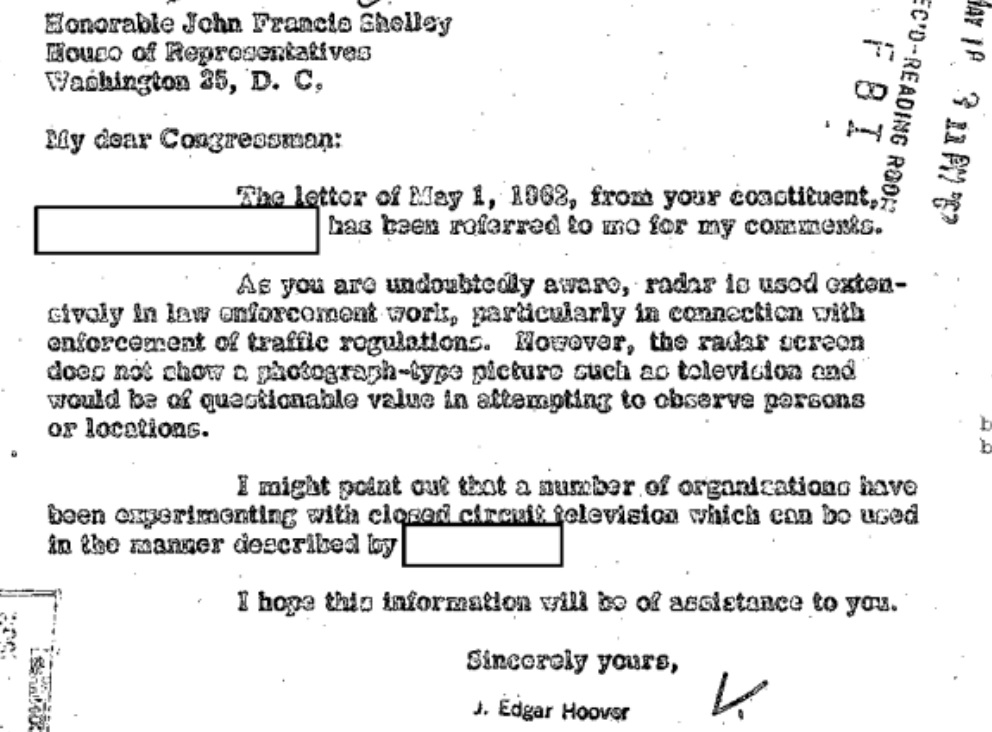

While none of that information made it in the file, it does include Shelley passing on a constituents’ suggestion to use 24/7 radar surveillance to stop all crime.

To which Hoover responded, “we’re working on it.”

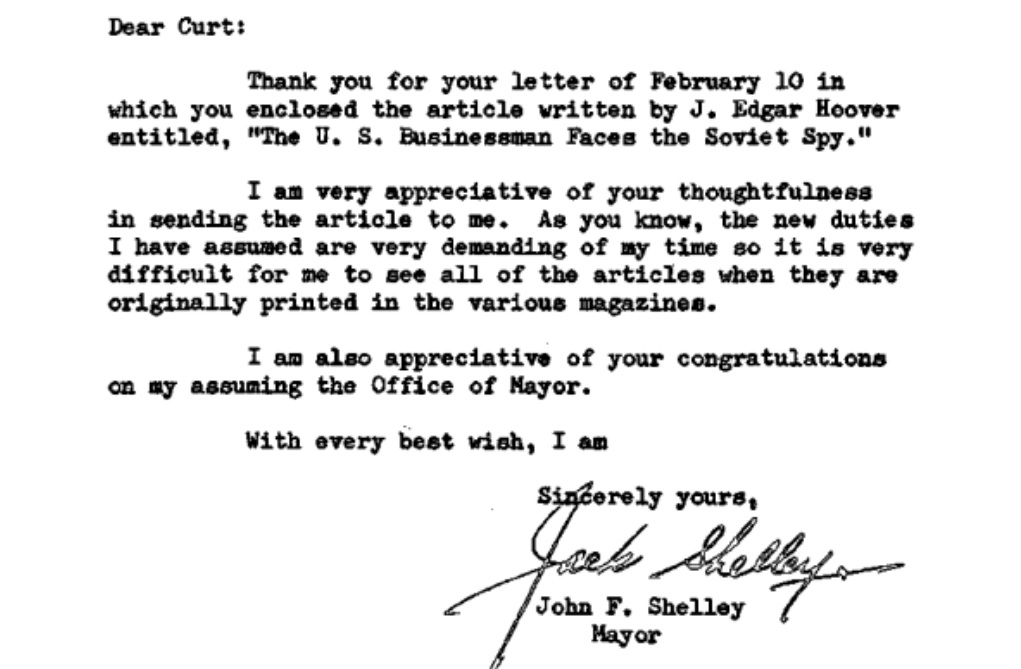

Their last exchange came after Shelley had left Congress to become San Francisco’s first Democratic mayor since 1910. An agent had sent Shelley a copy of Hoover’s latest article about the Soviet threat, and Shelley had written back a letter of appreciation.

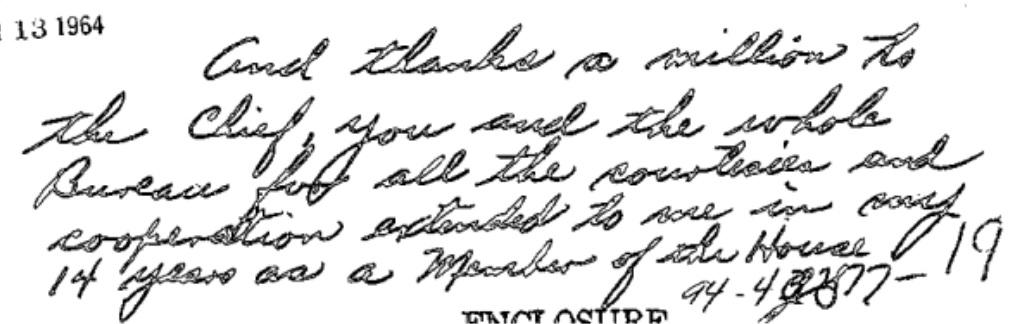

The agent forwarded the letter to Hoover, telling him to check the note at the bottom …

which if you’re having trouble deciphering, was helpfully transcribed by the Bureau.

Who says subversives can’t be sweethearts? Read the full file embedded below, or on the request page

Image via Mike Lynch Cartoons