Thanks to a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism, I had the privilege of visiting both North and South Dakota and speak with witnesses and victims of the widespread police violence that occurred on the north border of the Standing Rock Reservation. There will be plenty of follow-up in the weeks to come, but while the memory is still fresh, I wanted to share an initial reflection from traveling to the treaty lands of the Dakotas

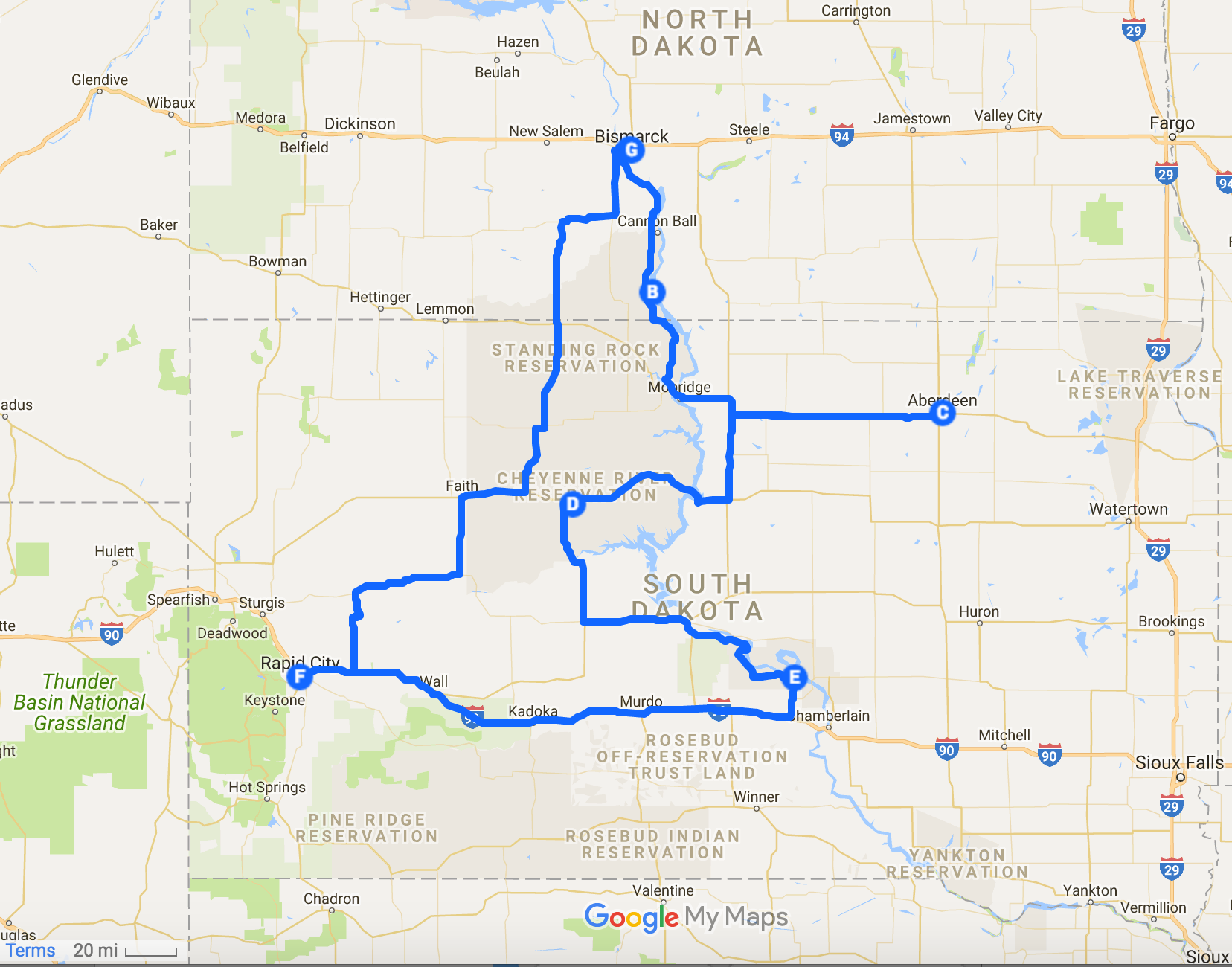

All told, I put about 1000 miles plus on a rented Chevy Malibu, going from Standing Rock Reservation in North Dakota, to Aberdeen, South Dakota, back across the state to Eagle Butte on the Cheyenne River Reservation, and then into the middle of the state to the Lower Brule Reservation. I ended up in Rapid City, South Dakota from which I made a six hour drive north back to Bismarck, North Dakota. On the way back north, I got the opportunity to drive through the Ȟe Sápa (Lakota for the Black Hills, a sacred location in Lakota culture).

In Standing Rock, I experienced the kind of wariness that comes from being part of a community which has experienced hordes of press, extreme brutality at the hands of law enforcement, and widespread infiltration by government and private security alike. One source of mine attributed the Prairie Knights Casino’s new policy of employees not being allowed to speak to the media to surveillance bugs that were found on casino grounds. Several sources told me that over 1,500 infiltrators were removed from Oceti Sakowin camp during the struggle.

This ongoing surveillance is something I heard more about when I crossed over into the Cheyenne River and Lower Brule Reservations respectively. Black Hawk helicopters still regularly do fly-bys of camps and the Reservations themselves, and multiple sources said unmarked police SUV’s still follow them multiple times a week, sometimes even when doing such commonplace things as going on morning runs.

On the Cheyenne River Reservation I met with Cody Hall, a Lakota youth advocate who coaches lacrosse teams and promotes healthy, active lifestyles for his reservation’s children. Hall told me of his dramatic arrest, and the savagery of the violence he saw law enforcement levy against overwhelmingly peaceful, even prayerful protesters. One theme I picked up on was the targeting of leadership, with arrests and rubber bullets alike, trying to cut off the movement’s organizing ability - a standard counter-insurgency tactic. From what I have heard from my sources on the ground, and confirmed by the Intercept’s leak of TigerSwan emails and reports, a true counter-insurgency operation was in effect against water protectors, something absolutely akin to what the US military has done in Afghanistan. Cody and the other folks I spoke to all agreed, ”It was a miracle no one was killed.”

Image via The Intercept

In Lower Brule, I had the distinct pleasure of meeting with Manape LaMere, an Oceti Sakowin headman, who helped explain to me the culture and history of the Indigenous people who are being confronted with the Dakota Access and Keystone XL pipelines, the organizational structure of the water protector camps, and broke down the violence and desecration of Oceti Sakowin sacred sites and objects. LaMere was part of the council of Oceti Sakowin leaders who interacted with government in an official capacity, and took time to tell me the full narrative of the movement from beginning to end, and its strict adherence to traditional practices and beliefs. Something that stood out to me everywhere I went was the militancy against alcohol or drugs, not only in Oceti Sakowin camp, but in the other smaller camps still protesting.

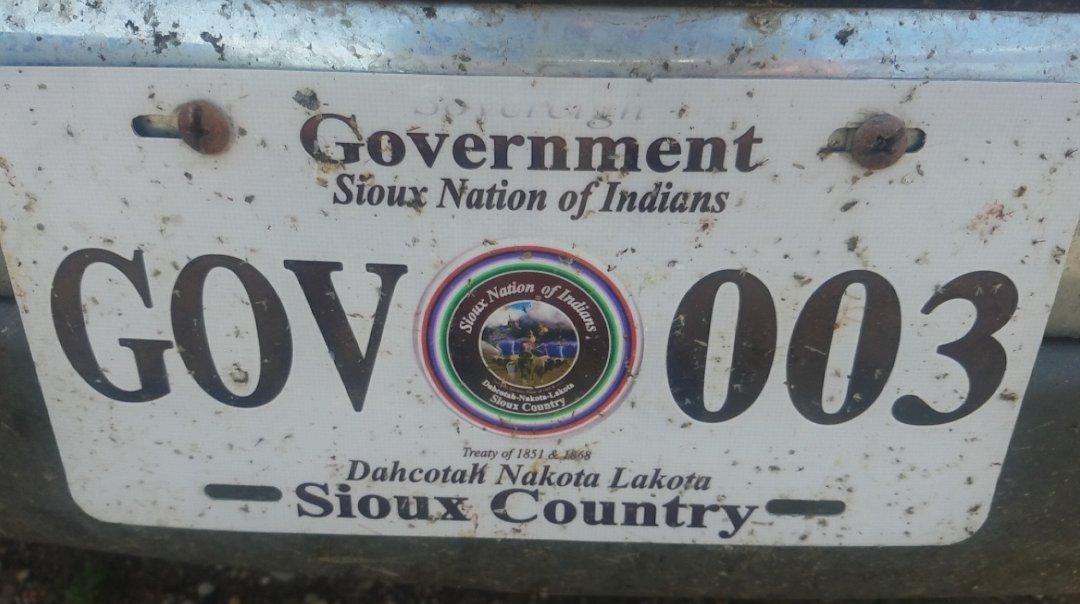

As a headman (spiritual leader for Lakota/Dakota/Nakota people), Manape was also able to explain to me why the term Očhéthi Šakówiŋ is fast becoming the preferred name of the people that are more commonly called Sioux. The word Sioux comes from an Ojibwe insult meaning “little snakes” which the French bastardized. Očhéthi Šakówiŋ, also written just Oceti Sakowin, means Seven Council Fires, which refers to the political structure of the Great Sioux Nation before colonization. The Seven Council Fires stand for the seven distinct subcultures of the Oceti Sakowin-making up the three overarching cultures, the Lakota, the Dakota and the Nakota. Of these three, the Lakota and Dakota share mutually intelligible languages and cultural similarities, with the Nakota speaking a different Siouan language and now mostly going by the name Assiniboine and mainly residing in Canada. Whites never seemed to realize that the Oceti Sakowin had had their own governmental structure, however different from those which rose from Europe, and had already established this confederacy hundreds of years prior to the first French explorers reaching Minnesota and the Dakotas.

The taking back of traditional terms and political structures is part of a larger movement within Oceti Sakowin territory, which aims to empower Indigenous youth to seek something greater than the poverty of Reservation life, and to remind them of the greatness that their people once had attained on the plains and in the forests. Around Standing Rock Reservation alone I saw several ‘Bring Back Lakȟótiyapi! Help Teach Our Children Lakota Language!’ bumper stickers. Mr. LaMere had ‘Sioux Nation of Indians’ government plates on his truck. Note the word sovereign up top in silver. And it seemed like everyone I spoke to was involved with organizing a powwow, the upcoming Sun Dance ceremony in July, or other traditional Oceti Sakowin ceremonies. That was in addition to PTSD meetings for water protectors, community health forums, and tribal council hearings. The air vibrated with the energy of organizing, and flyers covered the pinboards of Tribal Administration buildings.

A decolonization movement is gaining strength, and is a huge part of why so many tribes from around the nation answered the call and went to protect Standing Rock’s water resources. An Apache college student named Jordan Anderson, originally born in Arizona but who had spent most of his life in Aberdeen, South Dakota, told me that among his own people back in Arizona there was a what he termed a youth cultural education movement. In fact, Anderson’s first language was Apache. Whether Standing Rock has truly set in motion a new era of Native activism and social change remains to be seen, but Anderson saw many reasons to be hopeful. “We have an opportunity to save something that was in our stories, that was our history,” he said. “There’s people out there educating themselves. And people have seen that regardless of the histories between different tribes, there’s way more power when you come together as a unit, and building those connections needs to start now.”

While that is an encouraging sentiment, it was in contrast to to the extremely harrowing things that Tanyan InajinWin, an Oglala Lakota mother, had to tell me when I met her in Rapid City, just across the border from the Pine Ridge Reservation. InajinWin, who served in the Marine Corps, described her lingering health effects from violence that was visited upon her during her time as a water protector, and told me, “I still have nightmares about the frontlines.” Never mind the psychological trauma of witnessing and feeling so much pain, she also stressed her belief that there needs to be a public health study done to research the effects of not just uranium mining, but the police violence at Standing Rock. I was assured that there are plenty of others who suffer from odd and terrible health effects, and I aim to speak to many of them on my return trip and truly document the damage done to water protectors.

An extra facet in all this that is not to be ignored is a strain of virulent racism against Indigenous peoples in the Dakotas. All of my sources, including InajinWin had poignant accounts to share - I heard multiple stories of shops refusing to sell to “Indians,” and of how active KKK chapters are in the region. In 2013 neo-Nazis held a rally in Leith, North Dakota with the North Dakota Highway Patrol (where Kyle Kirchmeier was then a Captain. Kirchmeier became infamous for being the Morton County Sheriff during the Standing Rock protests) and Grant County Sheriff’s Office, allowing the white supremacists to hold their gathering, while facing down the Indigenous counter-protest. Earlier this year in May at an EPA uranium hearing attended by InajinWin in Edgemont, South Dakota, Indigenous activists received an outpouring of racist backlash. A Southern Poverty Law Center hate map shows how rife with white supremacist groups the Black Hills area alone is.

You can look for my more detailed reporting on the evolution of police militarization beginning next winter, and I look forward to writing a more complete account of what happened in Standing Rock. However, many of the issues I discussed with these people were about things that have been serious concerns in Indigenous communities long before the events of Standing Rock. A history of systemic racism, police killings of unarmed Native men and women, corruption, poverty, and broken treaties have been a part of government-tribal conflict for years, and not only go largely unaddressed, but are woefully undercovered in US media.

So beginning this summer, MuckRock will attempt to give these issues the coverage they deserve - you can expect us to open up some public records projects on issues along these lines, and hopefully collaborate with an Indigenous outlet or two.

We have already begun filing with the South Dakota Governor’s Office to assess their communications with Reservations within the state’s borders. You can follow those requests here.

Image by Curtis Waltman