The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), like all government agencies, produces a huge amount of paperwork. Faced with this quantity of paper, the CIA published a classified collection of essays that was aimed at improving the literary quality of the documents that the Agency was creating.

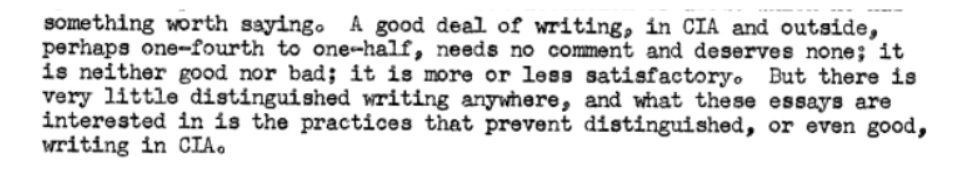

The anonymously authored collection, which criticizes the quality of the Agency’s writing unsparingly, begins on a grim note, claiming that “perhaps one-fourth to one-half” of CIA writing “needs no comment and deserves none; it is more or less satisfactory” and devotes itself to discerning “the practices that prevent distinguished, or even good, writing in CIA.”

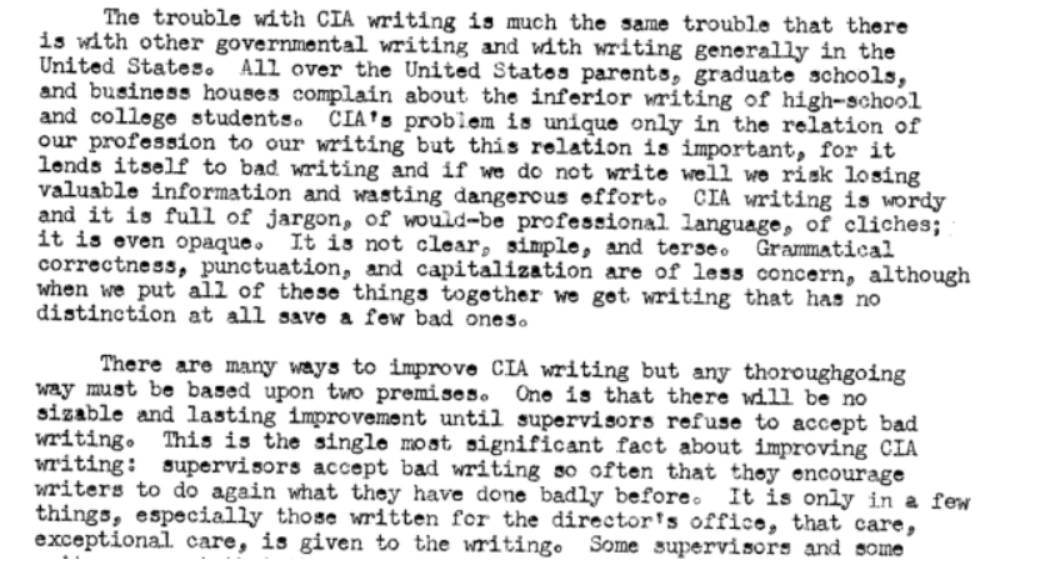

The problems the essays address include both specific problems of style - it says that CIA writing is “full of jargon, of would-be professional language, of clichés; it is even opaque” - but also include a problem of culture at the CIA that the authors believed would tend to produce poor writing.

“There will be no sizeable and lasting improvement,” the document says, “until supervisors refuse to accept bad writing. This is the single most significant fact about improving CIA writing.”

In light of these strong objections to the status-quo, the document provided a number of writing tips that were aimed at dealing with the problems it saw as most prevalent in the agency’s written output. The advice for agency writers includes:

Avoid Jargon

Of the Agency’s tendency to use specific terms of art or internal slang, the classified report says “The chief and worse aspect of CIA writing is the failure to let words say what they have to say, to use simple words and let them alone. The result of this failure is a thick paste of words, a conglomeration of jargon, cliches and euphemisms, of redundancies, pomposities and irrelevancies, that instead of accomplishing more accomplishes much less.”

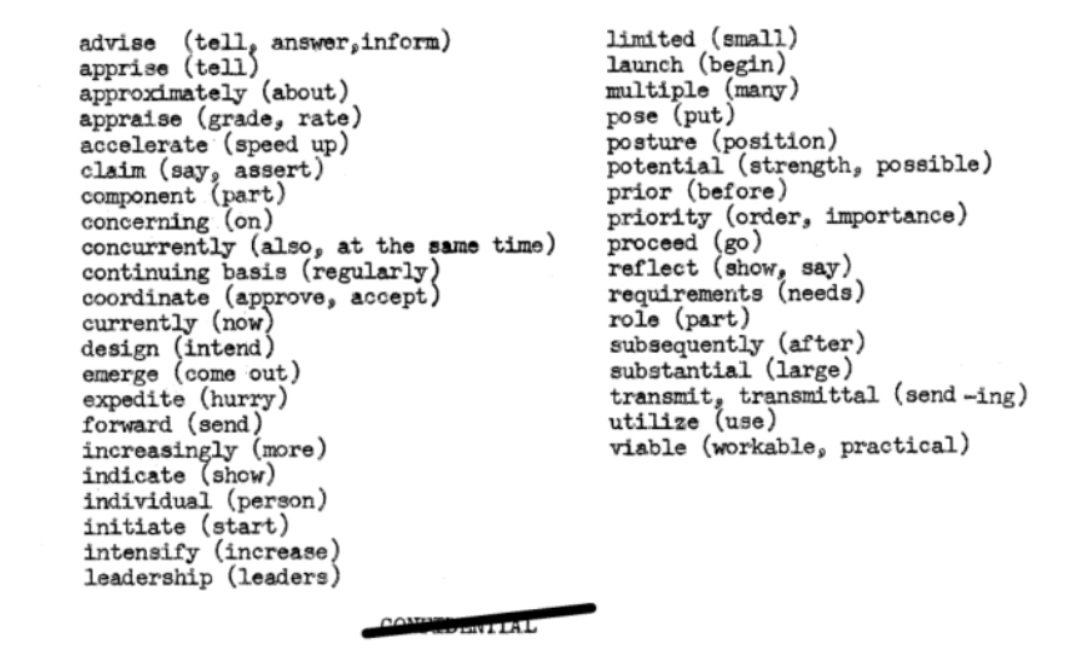

The essays also include a list of words that it considers to be “new jargon” or needless replacements for existing words.

These words, the anonymous essayist argues, are used because of “zeal to make our writing sound pretentious and professional.”

Capitalize Carefully

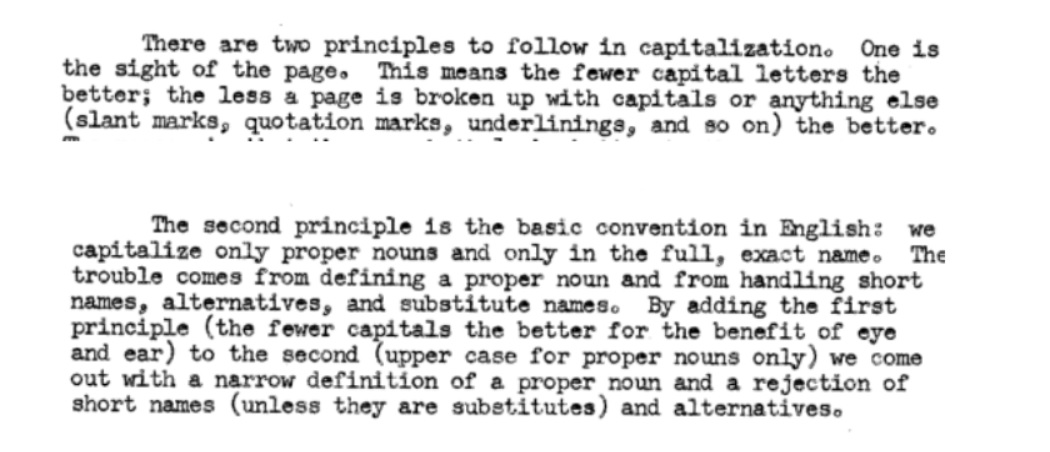

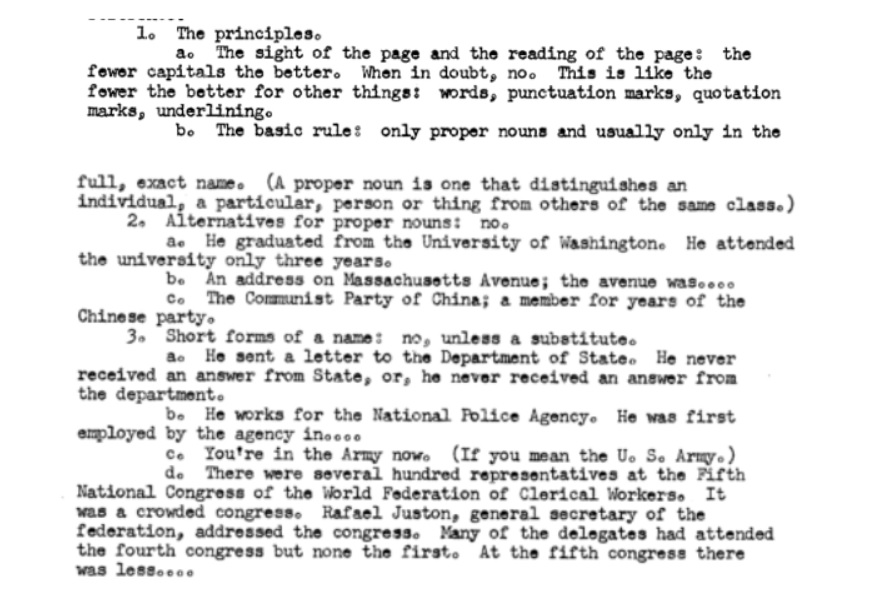

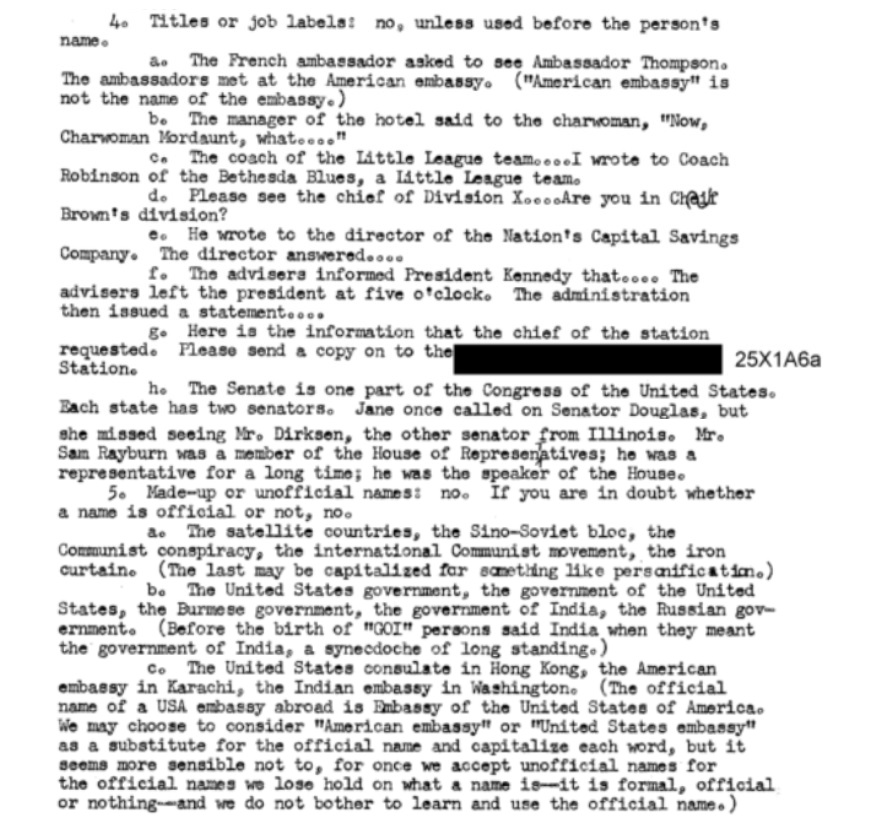

The document recognizes that rules for capitalization vary, but attempts to provide a consistent set of standards for the CIA’s writers based on two main principles, keeping each page clear of unnecessary punctuation and capitalizing only proper nouns.

Though these rules may appear simple, the document elaborates on them with a five-point guide aimed at dealing with nearly every question of capitalization that CIA personnel might encounter.

Avoid the Passive Voice:

Like many advocates of clear writing, the CIA’s anonymous essayist strongly urged writers to avoid the passive voice. “Nine times out of ten,” the document says, “we use the passive voice out of indolence or caution; we are either too lazy to find the active-voice phrase or we are too cautious to risk it.”

The passive voice’s prevalence in CIA writing, the essay argues, means that “it will take two acts to get rid of it: recognition and will power.”

The section on the passive voice ends with a paragraph enthusiastically describing the benefits of the active voice:

The 56 page document ends with a proposal that the Agency create an internal apparatus aimed at monitoring writing quality, but recognizes that writing well can be difficult

Browsing through CREST will show you that the advice in the essays was, to put it mildly, not always followed.

The full document is included below.

Image by Dennis Skley via Flickr and licensed under Creative Commons BY-ND 2.0.