Tomorrowland opened at Walt Disney’s California Disneyland on July 17, 1955, offering spectators “astounding exhibits of advanced science, developments presented by America’s leading industrial firms.” The corporate consumption driven imagining of the future featured video telephone conversations and super fast cooking ovens, but luckily no visions of the future of law enforcement.

Image by bananaphone5000 via Photobucket

…. But not for lack of trying. If Disney and the FBI had had their way, children’s shows and amusement park rides could have normalized law enforcement - specifically scientific and futuristic law enforcement - for entire generations of Dumbo-loving children.

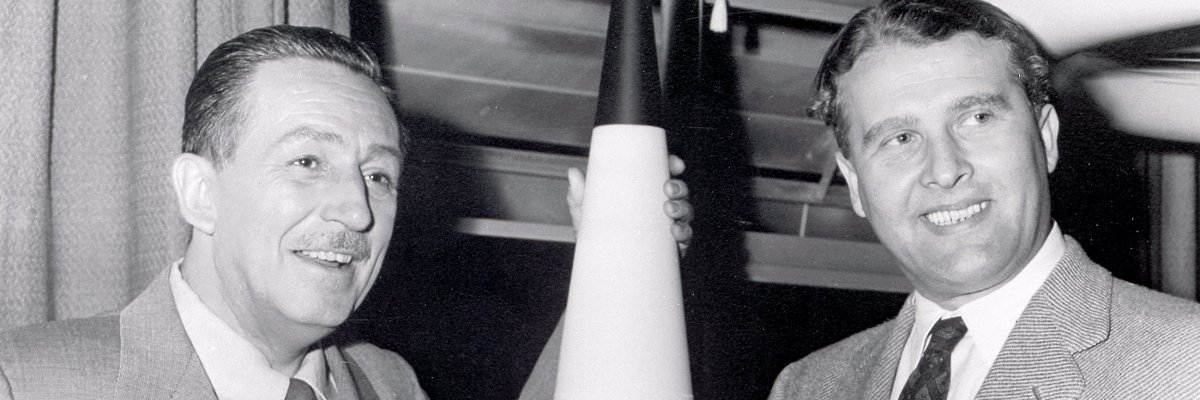

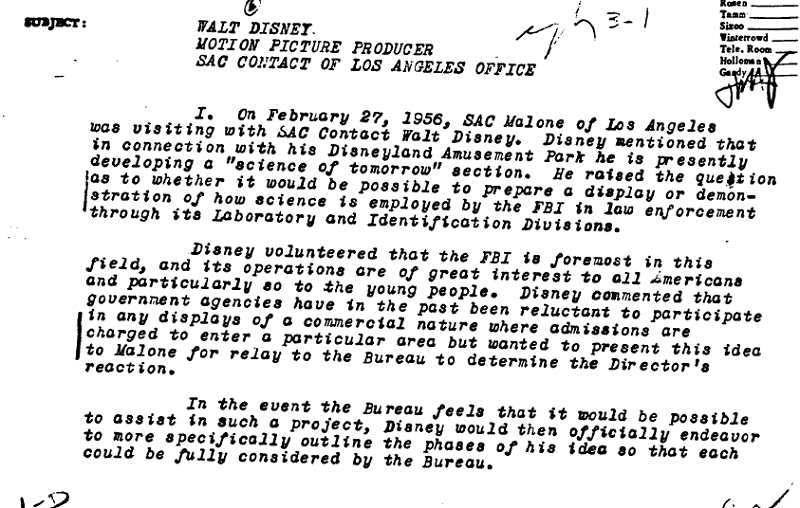

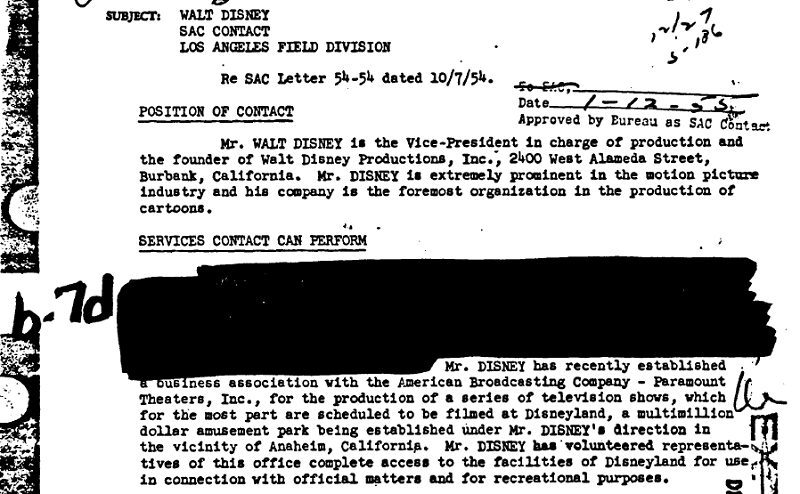

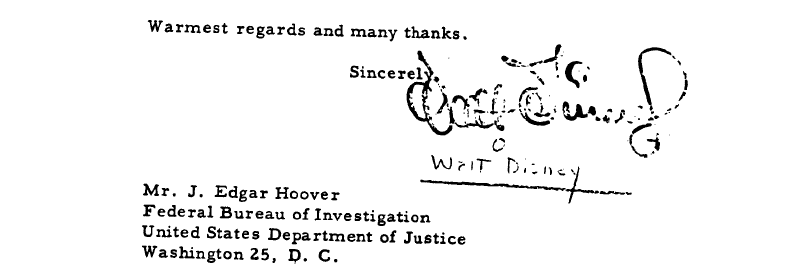

One year after Tomorrowland’s official opening, Walt Disney’s FBI file records a meeting between the Bureau’s Los Angeles Special Agent in Charge (SAC) and our imaginative childhood hero, Walt Disney. Disney called the meeting to try to include the FBI into his vision of the future.

The document highlights the effective one-two punch of the FBI’s Cold War tactics: an aggressive public relations campaign, and sweeping program of invasive and illegal surveillance. Long before Walt Disney invited the Bureau to imagine this future, he assisted in the FBI’s with these two projects.

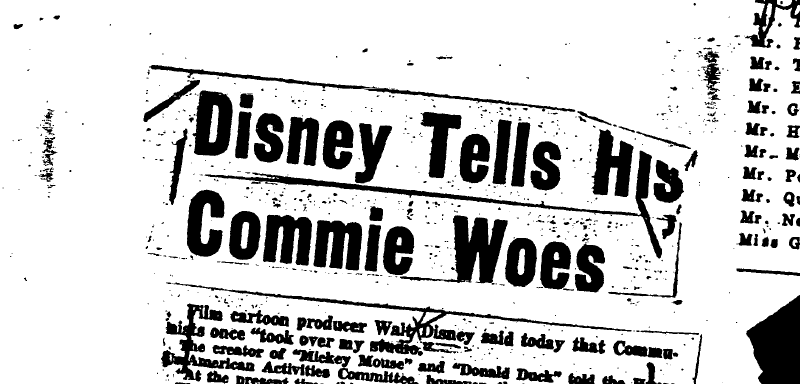

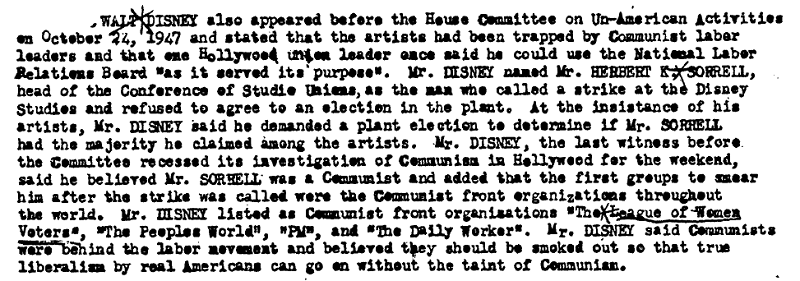

In 1947, the same year J. Edgar Hoover and Walt Disney struck up their long friendship, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) unveiled their first Hollywood blacklist. This friendship was initially situated on Disney’s eagerness to inform the FBI on how “communist infiltration” had caused his animators to go on strike in 1941.

According to the union’s leaders, the strike was caused by Disney’s firing of employees for union activism. The whimsical Walt Disney disagreed.

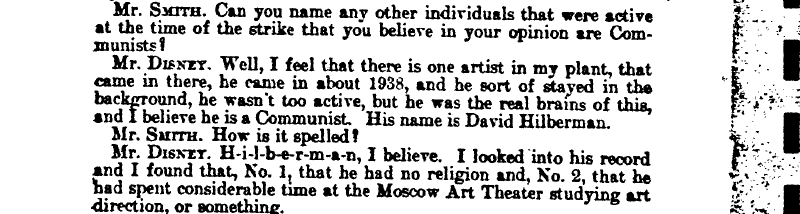

According to his 1947 HUAC testimony, communists caused the strike. Perhaps because he was aided by information from the FBI, Disney became more confident than ever that animation legend David Hilberman was some sort of twisted radical because he discovered, “1. That he had no religion and No.2, that he had spent considerable time at the Moscow Art Theatre studying direction, or something.”

This collaboration was so fruitful, that by the time of Tomorrowland’s opening in 1955, the FBI was already referring to Walt Disney as close “Contact” of the Special Agent in Charge - and noting that Disneyland was offered to the Bureau for “official matters and recreational purposes.”

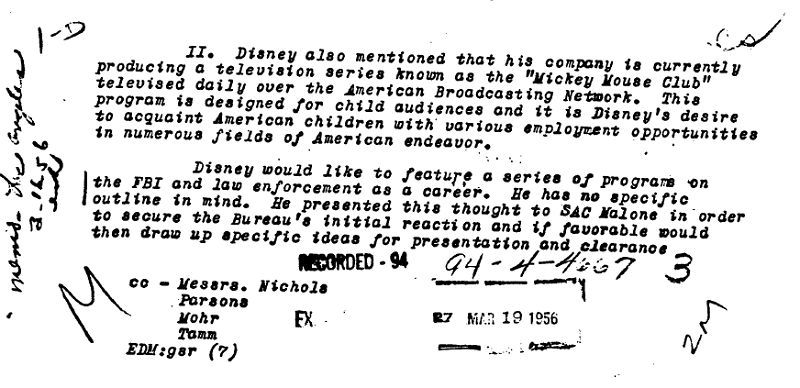

Giving the Bureau a coveted spot in the “science of tomorrow” wasn’t the only way Walt Disney planned to catapult the FBI into the imaginations of American children. Between January 1956 and December 1957 Disney repeatedly approached the Los Angeles office about devoting an episode of the beloved children’s show “Mickey Mouse Club” to the FBI.

Although the objective was to, “acquaint American children with various employment opportunities in numerous fields of American endeavor,” the initial pitch was declined, but after years of negotiation, the episodes eventually aired in January 1958.

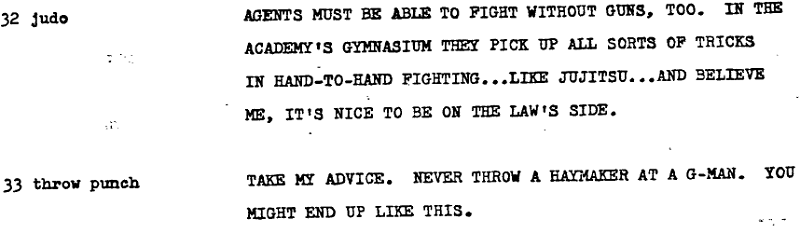

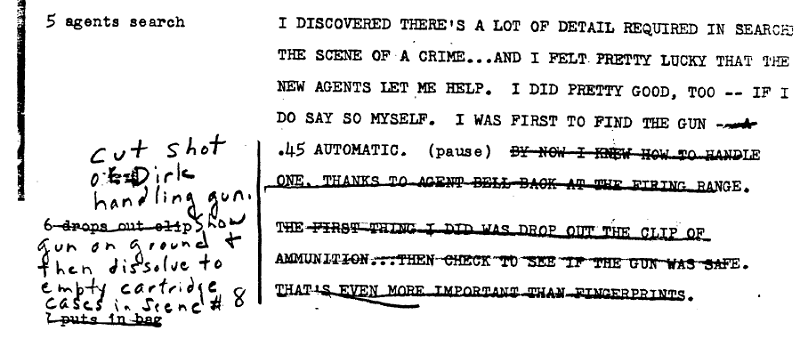

The Orwellian script has been immortalized within Walt Disney’s declassified FBI file. The script follows the precocious Dirk Metzger, a 13-year-old Mickey Mouse Club reporter and the son of a Marine Corps Colonel, as he meets J. Edgar Hoover, watches agents shoot at a fake Baby Face Nelson, and gets his fingerprints taken.

He also gives salient advice to kids like, “take my advice. Never throw a haymaker at a G-man.” The comfort this kid exhibits while learning about FBI investigation tactics and seeing agents shoot at targets with a name and a face is terrifying and exactly to the point. If Dirk Metzger is comfortable with trench-coated agents, why shouldn’t we?

Before the show could be made however, the FBI sent Disney three pages of script revisions including taking the gun out of Dirk’s all-American hands. “The handling of a supposedly loaded weapon by a boy of Dirk’s age is not considered appropriate,” a memo from October 22, 1957 reads.

In the 1950s, the government only seemed to be watching and listening to everyone because of a prolific public relations campaign that normalized and justified surveillance. Today, the government really is watching and listening and it’s taken its toll on our imaginations. The day Walt Disney tried to give a spot in Tomorrowland to the FBI was the day children wearing Mickey Mouse ears almost lost their ability to imagine a future without policing.

The largest of the files has been embedded below, and the rest can be found on the request page.

Image via Wikimedia Commons