After a public records request, the Boston Police Department has released its procedures regarding the handling and recruiting of confidential informants. Dated March 1, 2006, and dubbed “Rule 333,” it contains the classification of types of informants, informant restrictions, recruitment procedures, and the responsibilities of supervisors from the detective all the way to the head of the Bureau of Investigative Services.

Rule 333 designates three types of informants:

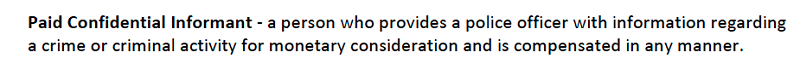

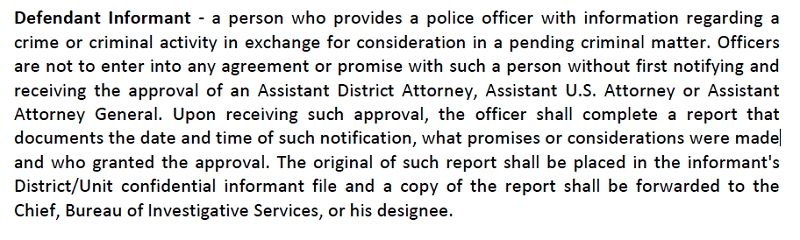

“Paid informants,” who expect monetary compensation for their information.

“Defendant Informants,” who provide information with an expectation of receiving special consideration in a “pending criminal matter.”

And finally, “Other Informants” whom the police department speculate are often motivated by revenge or rivalry for those being informed upon.

The term by which the department manages expectations for any interaction with an informant is that of “Significant Contact,” defined as any contact or communication, planned or unplanned, which provides information that can be used as the basis of an arrest or search warrant.

In terms of recruiting confidential informants, the department lays out a number of restrictions, including seeking special permission to utilize people on probation or parole as an informant, and acquiring written consent of a parent or legal guardian before allowing anyone under the age of 18 to become an informant of the police department.

Even those who have been otherwise disqualified from becoming an informant can still be used on a “case by case” base with special permission.

So how does an officer go about making an average citizen an informant for the Boston Police Department?

The first step is initial contact and reporting that initial contact to superiors. Then comes a criminal background check and a meeting with the detective’s supervisors to determine their credibility and present documents that verify their identity. Once this is confirmed, the exchange is made more formal with the creation of two Confidential Informant Cards and a recent photograph of the new informant.

In the informant is approved, their real name is replaced by a code and all future interactions are supposed to be meticulously recorded and any meetings must occur in the presence of a second officer.

The handling officer is also prohibited from having any other meetings with the informant that are not explicitly about intelligence gathering.

According to the document, the Detective Supervisor is responsible for approving or rejecting any payments to informants up to $250, and any amount higher than that must be approved by the Chief of the Bureau of Investigation and the officer is prohibited from paying for information straight out of their own pockets.

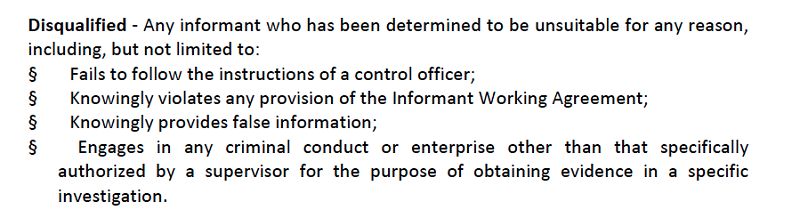

Informants can also be disqualified for service for a number of reasons, including committing crimes other than those authorized by the police department for the purposes of obtaining evidence.

As indicated in the document, informants are required to sign an informant working agreement which lays out the particulars of their tenuous employment, their rights, and their responsibilities. I have filed a request for this document and will continue to report on the issue of informants as more is released.

While none of this information is incredibly shocking for anyone with a working knowledge of police intelligence gathering, the release of this information provides the public with a more thorough understanding of the modes by which the police department allows itself to interact with citizens and how public money and resources are allocated to maintain law and order.

Read the full rules and procedures on the request page, or embedded below:

Image via Boston Police Department