As do private citizens, some ATF and DEA agents use their smartphones to sext each other. But we must hazard a guess as to the size of the issue, according to a recent inspector general report.

Why? Because neither the ATF nor the DEA bothers to hold onto its sexts, or any other text messages, for that matter. Whether tasteful or harassing, dick pics or dirty talk, the Justice Department can only track down such sexually explicit communications by confiscating the offender’s phone or asking politely for a peek.

The FBI and US Marshals do a slightly better job, but inadequate archiving exposes all four agencies to uncomfortable questions about the integrity of its recordkeeping around misconduct and criminal cases alike.

The inspector general report, which was released in March, tackles the Justice Department’s handling of sexual misconduct and harassment allegations. Its recount of overseas sex parties and brothels nabbed considerable media attention and an awkward congressional hearing. The firestorm cost the DEA chief her job.

But the entire chapter dedicated to sexting was lost in the report’s sea of naughtiness. In particular, few noted the red flag that the Justice Department is not adequately equipped to preserve agents’ text messages, clean or otherwise. This gap has troubling implications not only with regard to agent misconduct, but also for the government’s ability to uphold the rights of prosecuted suspects.

Of the four federal law enforcement agencies, the worst by far are the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) and the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). Officials from both agencies told the inspector general that they “lack the technology to archive such material.”

When allegations of textual misconduct arise against a particular employee, both agencies rely on the suspect to hand over damning messages or relinquish the device. The report notes considerable risks with this approach, namely that the employee in question might not be keen to supply such information, might “adulterate the evidence by adding or removing language contained in the text message,” or simply delete incriminating texts altogether.

Short of a court order or forensic inspection of the device, deleted texts cannot be recovered. Since many cellular carriers keep text message content for a few days, if at all, a court order for messages can come back empty if it’s filed too late.

Forensic imaging can also prove futile if agents wipe their smartphones entirely. This happened in the investigation of DEA agents accused of arranging a prostitute for a Secret Service agent in in Cartagena, Colombia in 2012. One DEA agent who wiped his BlackBerry was charged with obstruction, but investigators were unable to recover potentially incriminating messages from the device.

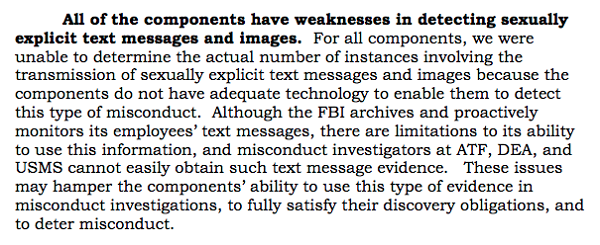

Prosecutors also rely on agents to hand over text messages that are “relevant” to criminal investigations. These texts can be critical to establish a timeline or to corroborate agents’ statements and courtroom testimony. For instance, following the May 2013 shooting of Ibragim Todashev, a friend of the Boston Marathon bomber, by an FBI agent in Florida, a string of text messages from a state trooper’s smartphone was used to fact check the agent’s recollection of the incident.

Based partially on the text message evidence, the Florida State Attorney’s Office found that the FBI agent’s use of deadly force was justified. While the Todashev report did not indicate how investigators obtained the trooper’s texts, prosecutors who work with the ATF and the DEA have no choice but to ask for “relevant” messages from the agents themselves.

Prosecutors are required to divulge evidence to the defense that is potentially exculpatory, as well as evidence that might cast doubt on the reliability of witnesses. The inspector general report gives the example of text messages that might reveal “a possible relationship, intimate or otherwise,” between a federal agent and a victim, informant or other witness “that may serve as bias or improper motive evidence.” At present, prosecutors must ask ATF and DEA agents whether they have any impeaching text messages on hand that should be passed along to defense lawyers.

The report highlights that such an arrangement is hardly ideal from a due process perspective.

Unlike the ATF and the DEA, the other two Justice Department agencies — the FBI and the US Marshals — archive their employees’ messages, but technical limitations remain. The FBI archives diagnostic logs rather than text messages themselves. The agency’s tech officials told the inspector general that such log data can be missing or corrupt, and that keyword searches are possible but tricky. In a 2010 court case highlighted by the report, the FBI was unable to produce text messages requested by a defense team because of such technical hindrances. The defendant, whose attorney emphasized the missing texts, was acquitted.

(Following a “rash of sexting”, the FBI disabled image transmission on all employee BlackBerry devices. It’s unclear whether this same prohibition will carry over as the bureau swaps over to Android phones.)

Where the FBI retains employee text message data for 25 years, the US Marshals does so indefinitely. In practice, however, the report found that prosecutors and misconduct investigators still ask agents to provide text messages that they deem relevant.

In light of such technical and procedural blockages, the inspector general recommended that the Justice Department should “acquire and implement technology and establish procedures to effectively preserve text messages and images for a reasonable period of time.” A roadmap for implementing the recommended changes is due on June 30.

In the meantime, we’ve requested materials from the Justice Department’s working group around text message archiving, as well as all four agencies’ current policies on preserving electronic communications deemed relevant to investigations.

Image by Tim Pierce via Wikimedia Commons and is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0