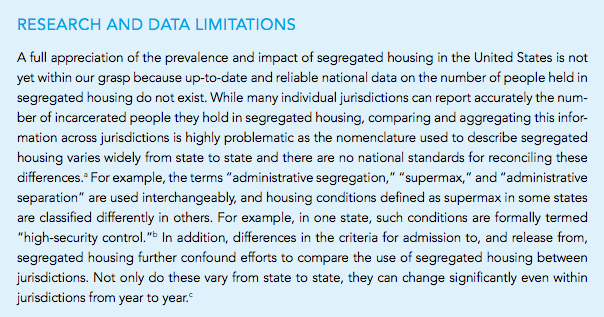

For a policy that breaks the prison population down to its most straightforward unit - one - solitary confinement and its use are notoriously slippery concepts to get straightforward facts on. The seemingly most enclosed system of state control over a citizen population, and the questions of “who, why, when, and for how long” almost never have a definite, down-to-the-human number for an answer.

The Vera Institute for Justice published a report in May on the dangerous misconceptions of solitary confinement and its application. It lamented the difficulty of more precise analysis simply because the necessary data is not available. Numbers available from the federal Bureau of Justice Statistics are unreliable; they don’t distinguish between types of segregated inmate and, even less useful, facilities aren’t required to report numbers at all, let alone accurately.

MuckRock has requested solitary confinement policies from each state-level Department of Corrections in the United States. Even though many agencies post relevant policies online, there are also occasions when what you see is not all there is - there may be additional policies that have been deemed worthy of exemption, and challenging that determination can be difficult if one doesn’t know that it’s been applied.

From the six New England states, MuckRock has received responses - either in the form of specific policies provided or direction to the policies’ online location - from each state save Massachusetts, which posts at least some of its directives online. There has been national reconsideration of the way solitary confinement is imposed. Correctional departments around the country have begun imposing policy changes to address indeterminate segregation and the general abuse or negligence that seems to accompany solitary; less progress appears to have been made on the useful data collection front.

Below is a brief introduction to solitary policies in the northeast pocket.

Connecticut

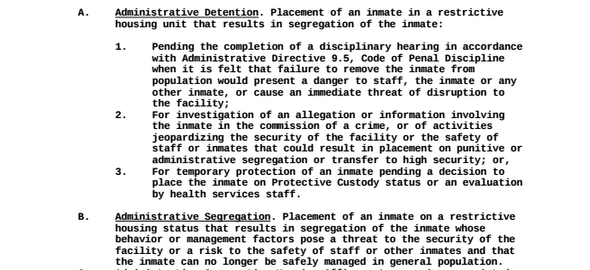

More than those of any of the other five states, Connecticut’s policies emphasize the “Security Threat Group” and how to handle it. The gateway state between New England and New York is home to some of the most dangerous cities in the east, and its policies reflect a wariness of in-custody gang relations. To be deemed a member of a Security Risk Group (SRG) is to enter the arena of prison discipline with one foot already in the SHU (“special housing unit,” a popularly-utilized term for solitary); such a label brings with it instant eligibility for more restrictive “Phase 1” housing and Administrative Segregation.

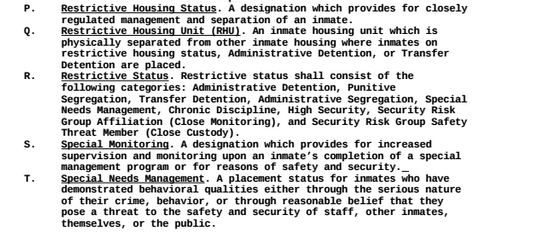

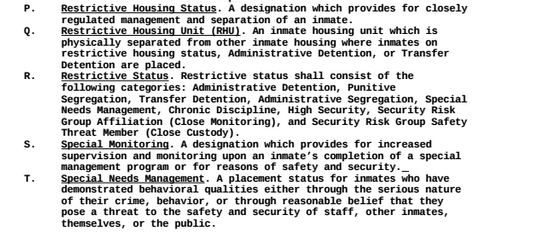

Connecticut’s policies offer a variety of scenarios that could imply accommodations for one: “confinement to quarters,” “close custody,” “high security monitoring,” “special monitoring,” “special needs management,” “ punitive segregation,” “chronic discipline status,” “administrative segregation.” These references to segregation-as-punishment don’t encompass the phrases used for solitary for other reasons: administrative detention, protective custody, transfer detention.

In 2001, Connecticut released a study on recidivism that found a 92% rate-of-return on those who’d spent time in administrative segregation. Subsequent reports seem to have cut out that metric, focusing instead on crimes committed before and after incarceration. However, that data seems as though it could be theoretically accessible; certain information is required to be kept track of in the State’s Statistical Tracking Analysis Reporting System (STARS).

MuckRock has put in a request for this data.

Maine

Maine’s efforts to reorient the use of solitary confinement have been lauded by the ACLU since policy changes of the last five years have gone into effect. Special Management Units (SMU) - which once held as many people in solitary in Maine as all of England - are being traded for alternatives to administrative and disciplinary segregation for punishment.

Massachusetts

The official term and rationale for placement in segregation is important in deciphering which methods of recourse are available for protesting the separation. An individual in one Massachusetts facility was held in administrative segregation in the “special management unit,” effectively awaiting further action, but, due to his placement in SMU, was not entitled to a hearing (which would have been an option had he been in the “departmental segregation unit”). A court later found that the ten months the man spent in segregated custody was unlawful. Nonetheless, Massachusetts stands by Arkansas as one of the few states where policy can keep an inmate isolated for up to ten years.

New Hampshire

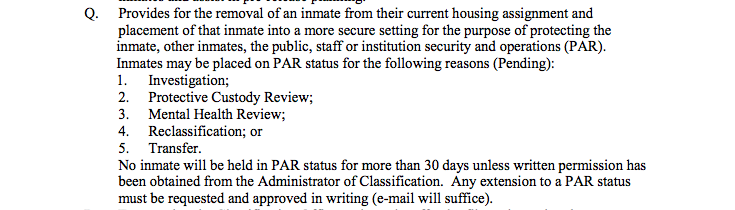

New Hampshire’s equivalent designation for those “awaiting further action” in solitary confinement is “Pending Administrative Review.” Their status is supposed to be reviewed weekly, while others in the SHU are up for monthly reevaluations. After three months, the Warden is the one to do the reviewing; after six months, the Commissioner is supposed to make the call.

Placement in the maximum security unit can be imposed for a range of reasons. There are the instances when PAR status applies, security classification (C-5) and protective custody, but also ABS (“Awaiting Bed Space”) status can be a factor.

Rhode Island

There are many similarities between the terminology that is used between states; many phrases are more-or-less the same, though this is another instance in which close doesn’t quite count. In Rhode Island, common vocabulary like “administrative confinement” (formerly known as “administrative segregation”), “disciplinary confinement” (formerly known as punitive segregation), and “protective custody” are supplemented by “observation” and “crisis management status” (policy 18.51-2) and the shorthand of “C” category inmates, which, by classification, have fewer housing and mobility liberties.

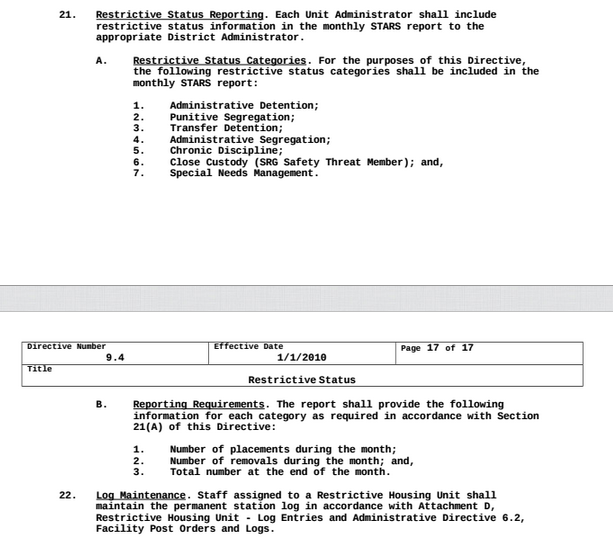

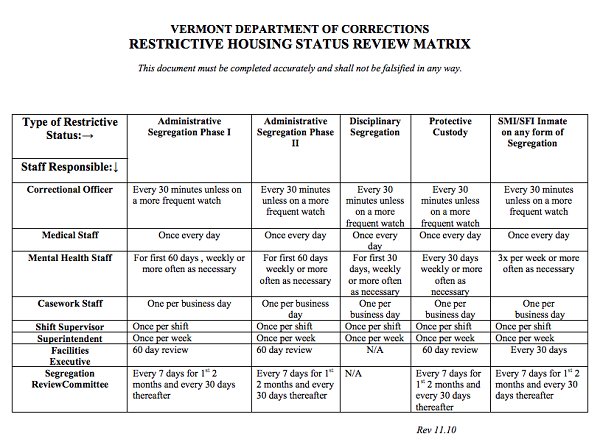

Vermont

Policy in Vermont dictates that those separated from the general population “will be observed in intervals not to exceed thirty (30) minutes.” Those under special observation will be checked on in accordance with the type of scrutiny they’re under.

Logs are kept to keep track of segregation confinement. However, their placement in Inmate Files makes them a standardly exempt piece of information.

Interested in solitary confinement policies in other states? Want to know how a particular facility has been handling special housing? Consult our map, find the reporting requirements, and let us know! We’ll start asking about who’s being kept behind locked doors in your state.

Image by Henry Hagnäs via Flickr and is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0