After nearly four years in self-described “FOIA University,” freelancer Phil Eil’s public record education is approaching graduate level status. The evidence records of Dr. Paul Volkman - whose “pill mill” court case sparked an “epidemic” discourse around prescription drug use in America - took years to obtain from the Drug Enforcement Administration, and even then, the majority of materials were withheld. Now, with the help of the Rhode Island ACLU, Phil is immersed in a court battle for full disclosure. We first spoke with Phil last year, and we caught up with him again for this week’s Requester’s Voice.

[Phil first submitted the request to the Executive Office of U.S. Attorneys, and it was transferred to the DEA, which took three years and twelve days to process it.]

Have you made any headway trying to obtain these materials in another manner? Have you been filing other requests (either related to this or otherwise)?

My FOIA request for the Volkman evidence was actually my last option. I only chose FOIA when all other avenues were exhausted.

Back in 2011 and 2012, after the trial ended, I thought - and I still do - that you shouldn’t have to file a FOIA request to access trial evidence. In some cases, like the trial of 9/11 conspirator Zacarias Moussaoui, federal prosecutors posted the vast majority of the exhibits online. I only filed a FOIA request for the Volkman evidence case after my requests to court clerks (at both the district court and the appellate court), prosecutors, and the judge were denied.

Then, once the FOIA process got underway and proved ineffective, my other FOIA-remedy options proved ineffective, too. Administrative appeals did nothing. Filing a complaint with the FOIA Ombudsman did nothing. Complaining to my U.S. Senators, Jack Reed and Sheldon Whitehouse, and U.S. Representative, David Cicilline, did nothing, in terms of getting these documents. Writing a letter to the President did nothing. Writing a letter to the House Oversight Committee did nothing.

So, the FOIA request was my last option, and within that last option, a lawsuit was my last option. This means that I’m infinitely grateful to RI ACLU and my lawyers, Neal and Jessica; with their help, I’m pursuing what I see as my last chance to access this evidence. If this lawsuit fails, I guess I’ll finally have to accept that these materials just won’t be released.

When we spoke a year ago, the estimated date of completion of the DEA request at that time was April 2015. What’s happened since then?

Well, the DEA actually met their April 2015 estimate. I’ll give them that.

But let’s not confuse completion with success. The DEA’s tenth partial-fulfilment package - much like the nine that preceded it - contained little in the way of substantive information. [It contained 3,288 processed pages and 2,867 of those (87.4 percent) were withheld. The remaining released 412 pages were aggressively redacted or largely blank and useless.]

So, the tenth and final partial-fulfilment fit perfectly with the pattern that my lawyers and I described in our March 18, 2015 lawsuit against the DEA:

“To date, the DEA has withheld 11,124 pages (87.4 percent) of the 12,724 pages it has reviewed of Plaintiff Eil’s request. To date, hundreds of the 1,600 pages produced have been largely redacted, making these documents effectively no more than blank pages.”

After the lawsuit was filed, the Rhode Island U.S. Attorney’s office (which is handling the case for the DEA), approached us with a proposed settlement - i.e. a release of the documents I’m seeking. We were skeptical, but agreed to put the lawsuit on “pause” to see what they would give us and then decide how to proceed. The RI US Attorney’s proposed-settlement release took place in two installments: July 29 and August 31.

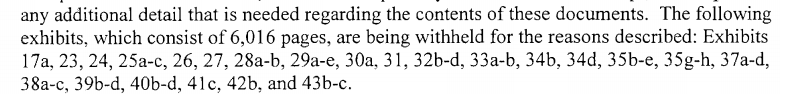

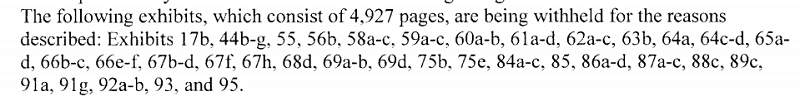

Here’s an excerpt from the July 29 cover letter :

And the August 31 cover letter:

Not only were over 10,000 pages and numerous exhibits still being withheld, but just as we saw with the DEA’s responses, the “released” pages were still being aggressively redacted.

There’s one more thing worth mentioning. Before the November phone conference with the judge, both sides of the case submitted brief summaries of their positions. (Here is ours and here is the DEA/R.I. US Attorney’s.) And the government’s filing included the memorable line: “Claimant Eil has not articulated a significant public interest that would be advanced through the disclosure of the medical records that he now seeks.”

Mind you, my lawsuit is about the government’s non-release of evidence from the trial of a guy the DEA initially accused of killing “at least 14 people”; who was on trial for prescription drug-dealing when White House released a report calling prescription drug abuse an “epidemic”; who was sentenced to four consecutive life terms in prison; and whom the DEA frequently mentions in presentations about prolific prescription drug dealers.

Despite the absurdity of this situation - being forced to argue why trial evidence should be public, in a country where the Bill of Rights guarantees public trials - my lawyers and I will be doing just that: presenting a case why this evidence (which, yes, happens to contain medical records) should be public. And we will be doing this, in large part, by pointing to the many times the DOJ has articulated a significant public interest in this case.

How many documents have you gotten in all? Has the ratio of redacted elements improved?

In order to tell you the exact documents-shown-at-trial vs. documents-released-after-the-trial ratio, I would have had to have been in the courtroom for the Volkman trial. But this didn’t happen because I was barred from returning to the courtroom, on Day 4, via a subpoena “For Testimony.”

With that said, I do have a 16-page list of exhibits that were shown during the trial. And, with that in mind, I recently estimated in an interview that I have “maybe 10 or 15 percent” of these materials. This is admittedly inexact. It’s tough to know exactly what you’re missing when you’re being stonewalled.

To your question about whether the ratio of redacted documents has improved, there’s a somewhat complicated answer. But it’s important.

In the more than four and a half years since Volkman’s trial ended on May 10, 2011, there have been three releases of evidence.

What’s really interesting - and disturbing - is how these three DOJ releases show three different standards of redaction. Putting the three releases next to each other makes you wonder if the DOJ is actually applying specific laws about medical privacy - which would presumably produce the same exact redactions and withholdings every time - or whether they’re just kind of improvising on a general theme of medical privacy.

And while we’re talking about inconsistency, I should mention how glaringly inconsistent these releases are with President Obama’s January 2009 FOIA memo encouraging agencies to administer FOIA “ with a clear presumption: In the face of doubt, openness prevails.” Throughout the FOIA process, I’ve seen the opposite of this attitude; in the face of doubt, non-transparency has prevailed again and again and again.

How have your feelings toward FOIA evolved since last we spoke and over the course of this experience?

I knew virtually nothing about FOIA when I filed my request in 2012. So my feelings have been entirely colored by this experience.

I now look at my FOIA request as a kind of quality control exercise - a random test of the system. Here I was, a taxpayer and journalist who strolled along and asked the federal government a very simple question: “Can I see the evidence that sent a man to prison for four consecutive life terms?” This should have been a layup; it turned into a “nightmare,” to use your memorable phrase from last year. The government has failed my quality-control test spectacularly. And the longer this litigation stretches on, the worse that failure becomes.

My current feelings about FOIA now align very closely with the testimony of Associated Press General Counsel Karen Kaiser before the Senate Judiciary Committee in May. She said:

We are witnessing a breakdown in the system – both on the procedural front, in the form of continual delays and agency non-responsiveness, and on the substantive front, with the vast over-use of exemptions and redactions.

Later, she added:

Non-responsiveness is the norm. The reflex of most agencies is to withhold information, not to release, and often there is no recourse for a requester other than pursuing costly litigation. This is a broken system that needs reform. Simply stated, government agencies should not be able to avoid the transparency requirements of the law in such continuing and brazen ways.

Compare Kaiser’s testimony with President Lyndon Johnson’s statement on the day he signed the FOIA into law, July 4, 1966:

This legislation springs from one of our most essential principles: A democracy works best when the people have all the information that the security of the Nation permits. No one should be able to pull curtains of secrecy around decisions which can be revealed without injury to the public interest....I have always believed that freedom of information is so vital that only the national security, not the desire of public officials or private citizens, should determine when it must be restricted....I signed this measure with a deep sense of pride that the United States is an open society in which the people’s right to know is cherished and guarded.

The Freedom of Information Act, as described by LBJ, is a beautiful thing. But the present reality, as described by Kaiser, is ugly. My case is a microcosm of the disaster FOIA has become.

Not only is my case perfectly exemplary of the “continual delays and agency non-responsiveness” and “vast over-use of exemptions and redactions” Kaiser describes, it’s worse. It involves senseless fees, like when, after sitting on my request for nine months and doing nothing, the Executive Office of U.S. Attorneys charged me $154 before transferring it to the DEA. It involves documented incompetence, like when my request was forwarded to the wrong DEA field office and accidentally deleted. And it involves shocking ignorance of the FOIA by government employees, as shown the day I called the DEA’s FOIA office and was denied an estimated date of completion by two separate people, including a supervisor.

It was only when I wrote the DEA FOIA office an email, citing the exact portions of the statute that guarantee me an estimated completion date, that I received one. But this didn’t change what had happened on the phone. It is a very bad state of affairs when a FOIA supervisor at the DEA is not familiar with the basic rights of FOIA requesters.

Or maybe she did know and intentionally denied me an estimate, which would be even worse.

Can you describe any surprisingly positive experiences in records requesting recently?

You’re asking the wrong guy. Because I actually don’t file that many records requests. I have enormous respect for people like you guys or Jason Leopold who file requests every day. But that’s not me. I really just a guy who filed one high-stakes request and continues to fight like hell to make sure it’s properly answered.

So my “surprisingly positive experiences in records requesting” come more from being a records-requesting observer than a participant. And I’ve got two stories. First, I got enormous inspiration from the Chicago-based freelance journalist, Brandon Smith - better known as “Reporter Who Forced the Release of the Laquan McDonald Video.” This guy is a hero. And he aptly summed up why this story matters in a recent tweet:

Smith’s story is basically the most empowering public-records story imaginable. And every journalist, journalism student, and citizen should know about it. (MuckRock’s Michael Morisy chatted with Smith last week.)

The other story isn’t quite a document-request story, but it’s close. In September, The New York Times published a story detailing how “Two top Army generals recently discussed trying to kill an article in The New York Times on concussions at West Point by withholding information so the Army could encourage competing news organizations to publish a more favorable story, according to an Army document.”

How did the Times get the key document?

The Times obtained the summary from a military official who opposed the Army’s plans to delay release of the concussion information. The official said not being transparent with journalists “damages democracy.”

Whoever that anonymous military official who leaked that doc is, I want to give him or her a hug. We need more - so many more - people inside government institutions with this attitude and the courage to act on it.

What struggles have you encountered not only in the process of gathering these records but also in discussing the failures you’ve experienced to other parties?

I’ve learned a lot of tough lessons at FOIA U. But perhaps the most disturbing lessons I’ve learned involve news media. In one instance, I watched a news outlet decline to cover my case, but join forces with a bunch of other news organizations to fight for transparency in the Hulk Hogan sex-tape civil trial. That, to me, was an interesting declaration of priorities.

In another case, an editor major national publication told me “as an actual reported article I don’t think it can work unless you manage to secure some more information.” This was essentially a statement that stonewalling stories aren’t newsworthy; you need documents in order to publish something. Needless to say, I disagree.

If you scratch a little bit deeper into my case, you’ll find it isn’t just the DEA failing to produce trial evidence, but the failure of everyone in a long chain, from clerks to congressmen. And if you scratch a little bit deeper, you’ll find that I was kicked out of a courtroom during the trial with a bogus subpoena and that I was intimidated by a DEA agent who offered vague references to “witness tampering” charges when I was conducting interviews before the trial began. So, to say, “we wouldn’t normally cover FOIA litigation” is to wave off writing about all of these things contained in my FOIA litigation story.

So, to my fellow reporters and editors, I say: despite what the Obama administration says, we are living in an age of non-transparency. The evidence of this is everywhere. And, if you are consciously ignoring or rejecting stories about stonewalling, or reporters being intimidated, or retroactive redaction, or FOIA litigation, you are tying your own blindfold.

Photo via Phil Eil