Jennifer LaFleur is the data journalism editor at the Center for Investigative Reporting. Previously she was the director of computer-assisted reporting at ProPublica. She’s worked in computer-assisted reporting for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, the San Jose Mercury News and the Dallas Morning News. LaFleur was the first training director for Investigative Reporters and Editors and co-authored their publication, Mapping for Stories: A Computer-Assisted Reporting Guide.

In this week’s Requester’s Voice, MuckRock catches up with LaFleur to talk request strategy, knowing your rights and the unintended consequences of going to court for a document.

What is your favorite FOI request?

I’ve been doing this for a long time, so I have lots of examples. I remember early on I submitted a public records request for the Adopt-a-Highway program database. So, a list of all the people who adopt sections of highway in California. There was some issue with whether or not people were doing a good job cleaning up their sections of highway. The request was denied on privacy grounds even though their name is on a giant billboard beside the road. We ran into a lot of privacy issues early on in California, which is a continuing issue here.

There was also an issue with people being attacked by dogs here in the Bay Area — this was a while ago — and the Mercury News asked for the pet license database and were denied again on privacy grounds.

The pet license data we never got and I can’t remember what came of the Adopt-a-Highway request.

How many times have you gone to court over a rejected or overly redacted request?

From all the news media places I’ve worked, probably 12 to 15 times. Obviously it was the news organization that went to court and not me. But they went to court based on something I was seeking.

What was the biggest win?

I remember all the bad things not the good ones.

Tell us about a loss then …

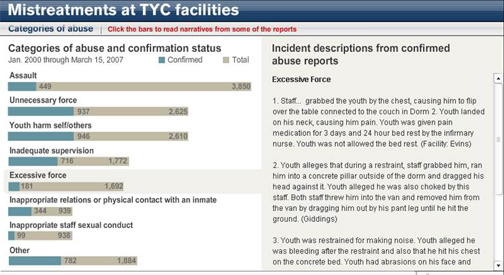

When I worked for the Dallas Morning News we had a recurring request for the personnel database for the state of Texas. We used that database for stories about prison guards in youth prisons who had criminal backgrounds and shouldn’t have been there, for example. In 2005 or 2006 they decided to deny us the dates of birth of public officials on the grounds that it would lead to identity theft of public officials, although they couldn’t show us one example of when that had happened.

In Texas, an agency has to get permission from the attorney general if they want to deny a public record. The attorney general found — in our favor — that these records should be released. At which point the comptroller’s office turned around and sued the attorney general’s office to prevent the records from being released. It went to a lower court, which ruled in our favor. The situation escalated all the way to the state supreme court where a partial court ruled that the record could be withheld.

After five years of fighting, that one really went on forever and then wound up not not working in our favor. That’s what happens when you take stuff to court: You risk setting case law and precedent. Often times negotiating is the better approach.

Talk more about going to court versus negotiating.

Nine out of 10 public officials will say “no” just to make you go away, and a lot of people just go away. We had a lot of cases in Texas where the paper had been denied records and nobody pursued it — often these were blatantly matters of public record. So often just the process of being persistent can pay off.

Working with FOI officers to understand where they’re coming from is important as well. Especially when requesting databases, it’s complicated. For example, when we were working with the centers for Medicare and Medicaid services to get prescribing data, we had a meeting where everyone was there — the privacy officer, their FOIA guy, their Medicare person, their technical people — so we could sit down and figure out a way that their concerns for protected information were met but we could also still get the data. And we did. So those conversations can be very helpful.

How often do you personally file a request?

When I worked for a daily newspaper it was probably weekly. At ProPublica it was based on projects. So a whole bunch at the front end of a project and then none for a while.

What percentage make it into a published story?

I would say eventually most of them do. It just depends on how much energy we’re willing to put in to negotiating and waiting.

What is your favorite tip or trick you can share with MuckRock users?

Know your law first. Know what you have a right to and what you don’t. Know how the law works. One thing in Texas that was very helpful for me was every year the attorney general actually held a training on the Public Information Act for public officials. I went to it and learned about all these scenarios that either were or were not matters of public record.

The American Society of Access Professionals is another good resource. It’s sort of a trade organization for federal FOIA officers. They do trainings all the time that are super helpful for better understanding FOIA.

Often times before I ever file a formal FOIA I will have a conversation with somebody about it. Sometimes I don’t even have to file a FOIA to get records. And even if I do, I have someone who can tell me exactly what I need to ask for.

When I first started working in California, I was looking for a database of all the highway accidents. No one knew what I was talking about until I finally talked to an actual person who said, “Oh, you want the SWITRS [StateWide Integrated Traffic Records System] database.” After I knew the secret name it was no problem.

Work with an agency, and you might find out that they have a report already that is 99 percent of what you want. States and federal agencies have retention schedules that they have to keep which often list the records they have and how long they need to keep them.

What does your FOIA process look like from start to finish?

The bulk of the work is before I even file a FOIA. Finding a blank copy of a form or getting a blank database entry can be helpful so that I can make an educated request. A lot of people then make the mistake of not following up. It frustrates information officers when they fulfill a request but the data never gets picked up. Go to the agency and pick up the information even if you’re not going to use it. Otherwise you send the message that requests don’t need to be fulfilled because no one is ever going to get it.

Follow up on your request. Do they need more information? Call in to see how it’s doing. A lot of that I do upfront so I’m not filing vague requests that nobody can understand. But keep following up.

If you’re rejected, know what the appeals process is. Many requests that are originally denied are filled on appeal. So it’s always worth it to appeal.

If the public really needs to know about it, write a story. If the state isn’t releasing data about nursing homes that’s something that people need to know.

Doing stories about public records is really important.

Image via CIROnline