For more than a decade, the Environmental Protection Agency hosted a portal for Freedom of Information Act requests used by dozens of federal agencies. The site, FOIAonline.gov, has been the key hub many journalists, academics, activists and the general public use to request and access public records.

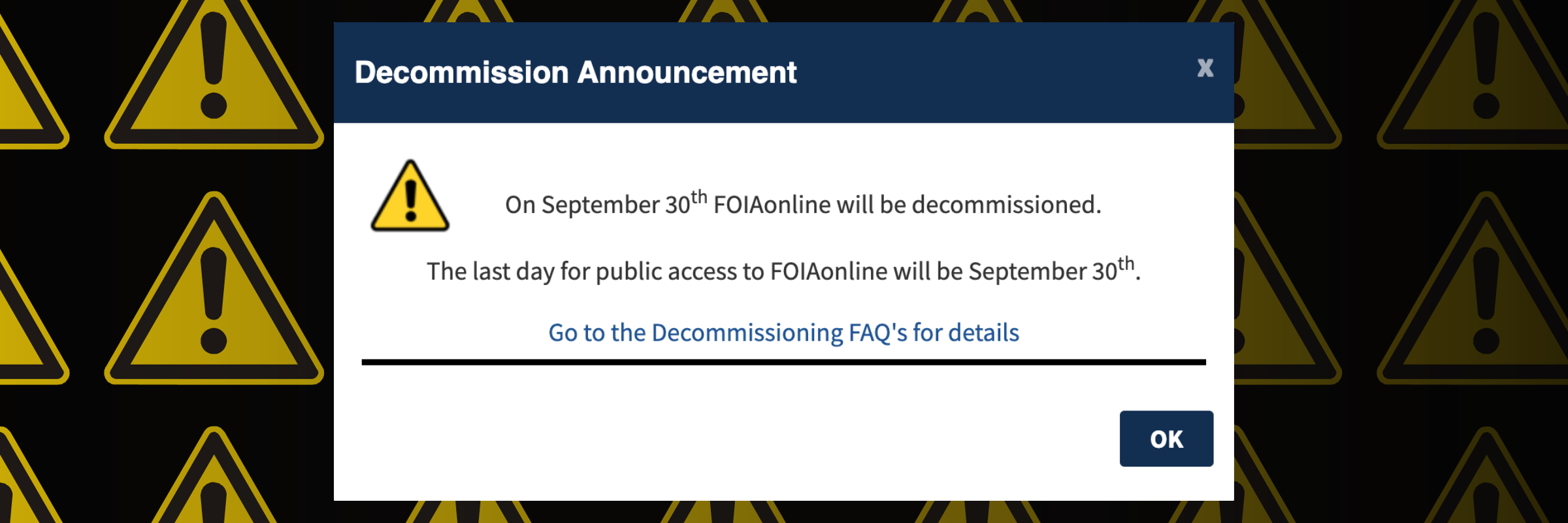

But on Sept. 30, FOIAonline will stop accepting new FOIA registrations and requests and begin the process of shutting down. The site’s administrators will work with partner agencies to migrate existing data and pending requests to each agency’s website, according to a “Frequently Asked Questions” document published on the site. A new tool, referred to as a “FOIA Wizard,” is being developed by the Department of Justice’s Office of Information Policy and could go live as early as this fall, the office’s director, Bobak “Bobby” Talebian, said in an interview with MuckRock. That tool, a mixture of machine learning and logic-based processing, could help users search for keywords related to their request and find what’s been previously requested.

The plan to decommission FOIAonline was made nearly two years ago, according to an EPA report, due to the high costs of running and updating the site as well as “problems experienced transitioning FOIAonline to operate in a cloud environment.” The federal government spent $2.7 million to run and maintain FOIAonline in the 2022 fiscal year, according to the EPA. Next year’s costs for FOIAonline, had it continued, would have risen to roughly $5 million, to cover help desk costs and rebuild code, among other improvements, according to budget documents obtained through a FOIA by Michael Ravnitzky, an attorney and FOIA expert.

But the government’s plan to shutter its FOIA portal struck even some of those with inside knowledge of the decision as short-sighted. In one internal email, also obtained through Ravnitzky’s FOIA request, EPA Chief Information officer Vaughn Noga wrote to a colleague in October 2021, calling the decision to close the site “fait accompli” and asking rhetorically: “There are huge optics surrounding this one. Remind me again the real rationale for displacing 22 partner Agencies?” (The colleague conceded to Noga that it was “a big change.”)

For those who used FOIAonline to file requests, alternative options to FOIAonline have not been clearly explained by the EPA or the Department of Justice’s Office of Information Policy, which sets the federal government’s FOIA policies.

Alex Howard, a longtime Freedom of Information advocate and former deputy director at the Sunlight Foundation before it closed in 2020, said the EPA and federal government was slow to tell the public about what the change ultimately means for requestors. Nine agencies have already left FOIAonline, including the Social Security Administration, the National Archives and Records Administration and U.S. Customs and Border Protection. The EPA, in a statement to MuckRock, said it would retain all of the data from FOIAonline and share it with federal agencies.

“The question now is, if it goes away, what happens,” Howard said.

We spoke to several Freedom of Information experts and the EPA about what comes next for those who request federal documents and data and how to best navigate the transition. Here’s what they told us.

FOIA.gov, reading rooms and a new FOIA Logs tool

FOIAonline is the only federal FOIA portal of its kind that allows users to search and filter by request language, agency or date range, experts say. It was also popular, with 34,000 active registered users and 1.5 million FOIA requests filed through the portal over its decade-long run, the EPA told E&E News. Without it, people who want to file FOIA requests, or see what has already been released, will have a much harder time.

“I will stress it will be a loss,” said Gbemende Johnson, a political science professor at the University of Georgia whose research focuses on FOIA and FOIA litigation. “There’s nothing else like it that had those multiple functionalities.”

For frequent FOIA requesters, or those looking to submit requests to federal agencies for the first time, individual agencies are still required to accept and process FOIA requests. Most agencies accept requests directly via email, U.S. mail, fax or individual portals.

FOIA logs, or detailed spreadsheets and databases showing what has been requested, released or denied, are valuable tools for academics, law firms, journalists and the public, said David Cuillier, director of the Joseph L. Brechner Freedom of Information Project at the University of Florida and member of the federal FOIA Advisory Committee. He added that a centralized system of FOIA logs would help the public see trends and spot issues that warrant further attention. (Disclosure: Michael Morisy, MuckRock’s co-founder and chief executive officer, served on the federal FOIA Advisory Committee from 2018 through 2022.)

“We’re the United States of friggin’ America. We can come up with something that works at a national level, just like many other countries,” Cuillier said. “It would make everyone’s job easier, I think. The government and the requesters…it’s just sad.”

The alternatives to FOIAonline aren’t perfect, experts say, but can fill some of the gaps.

FOIA.gov is the federal government’s central website for FOIA requests. It provides agency contact information and average processing times, along with links to FOIA libraries and reading rooms. To submit a request on the site, a user must search for or select the first letter of the agency from a dropdown menu. Users then go through a six-step process of filling out request information before finally submitting their requests. Users can search data on FOIA.gov, but it is limited. You can’t see comprehensive data or see what other users have requested.

Individual federal agencies also have their own portals where users can submit records, and some have features to search publicly-available documents like the National Archives and Records Administration. In 1994, amendments to the Freedom of Information Act required that federal agencies establish electronic FOIA reading rooms that included previously-released records and other agency documents. But there isn’t consistency among federal agencies, with some providing a search feature and others simply posting its data in blog-style lists.

MuckRock has also released a new tool — FOIA Log Explorer — that allows users to search through thousands of requests from dozens of agencies from the local, state and federal level. It takes that information and digitizes it for users, though some information may be more detailed than others because of how much each agency releases.

But the lack of a central FOIA repository for the public puts a burden on the requestor to know what is and isn’t available, said Rick Peltz-Steele, a professor at the University of Massachusetts School of Law who specializes in government transparency and media law.

“I think all of us in the FOIA community thought that, in the Internet age, we will be much farther along in terms of mass transparency,” Peltz-Steele said. “The advent of tools, such as MuckRock, are fantastic and take advantage of what the Internet can do. But there’s still no one-stop-shop.”

A ‘FOIA Wizard’ on the horizon?

The Department of Justice’s Office of Information Policy is working on a new FOIA tool, what it refers to as a “FOIA Wizard,” that would help users navigate FOIA.gov and submit requests. Similar to FOIAonline, the tool would allow users to see what documents are already public and what isn’t, as well as conduct more comprehensive searches. An “request for information” published in March 2022 by the DOJ notes that FOIA.gov has been the hub for education on FOIA policy, including annual reports and directions on how to submit requests to federal agencies.

“However, with over 100 agencies and over 400 components, members of the public often don’t know to which agency or component they should submit their request,” the RFI reads.

During a November 2022 public meeting of the Chief Officers FOIA Council, a federal committee that helps set FOIA policy, the DOJ announced that the “FOIA Wizard” project was in development. Slides from that meeting show that the tool would likely use a mix of machine learning and logic-based processing to help users find information but provided few additional details. The goal of the tool, according to the DOJ, is to provide “a more cohesive experience for the public and reduce misdirected or unnecessary requests to agencies.”

At another public meeting this year, Talebian said that the Justice Department took user and agency feedback into account in developing prototypes for the tool. The Justice Department awarded a $3.1 million contract over five years to a digital strategy firm, Forum One Communications, to develop the FOIA tool, according to federal contract details.

The federal contract with Forum One is set to run through 2027, with soft releases of the tool to go live over time, Talebian said in an interview with MuckRock. He added that the FOIA Wizard’s first release would occur sometime this fall. Talebian said that the goal would be to tailor the tool for two types of users: those who don’t know what they’re looking for, and those who do.

For requesters who know which agencies to contact for records, they would simply need to search the site for the agency page, Talebian said. The information specific to each component of the request would be populated and the requestor can send the request.

But for requesters who are unfamiliar with the process, the tool would provide a search field that can be a description or keywords of what they are looking for. The tool would then take them to the appropriate landing page, all of this done with the assistance of machine learning.

“That will be based off of a lot of data that we’ve taken from agencies and agencies’ websites, use a machine learning module to help the requester go either to the right place to submit the request, or if it’s already maybe on their FOIA library, directly to the those pages,” Talebian said.

He gave an example of someone looking for immigration records to highlight how the tool would work: After selecting immigration from a menu, the user would be directed to a series of of questions that would ultimately direct them to the right agency. He added that the tool would inform the user whether or not they would need to file a FOIA request to get that information they are seeking.

One complication with the tool is the lack of uniformity in FOIA portals and policies across federal agencies. Currently, FOIA.gov acts as a kind of go-between for requesters and federal agencies. Users submit their requests through the site, and the request is then sent over to the specific agency. After that, FOIA.gov doesn’t play a role in ensuring that records are delivered or that responses to requests are sent; that is the job of each agency, Talebian said.

“We don’t have the two-way kind of interoperability yet where you could set up an account and you can get responses back through FOIA.gov,” Talebian said. “But that certainly could be something that happens in the future as we’re continuing to build on, in or out.”