Public health experts have long warned that the true death toll of the pandemic in the U.S. is up to 15% higher than the official tally, leaving as many as 165,000 COVID deaths uncounted. But without an audit of official death numbers, the lives and details behind these deaths remain hidden. The Brown Institute and MuckRock’s Documenting COVID-19 project and the USA TODAY Network spent months investigating where and why COVID-19 deaths go uncounted.

For our Uncounted investigation, journalists from five newsrooms worked together to analyze CDC mortality data and follow that data to where it originates at the local level, through death certificates. We compared official COVID death figures with models developed by the CDC, in coordination with a team of demographers at Boston University; we collected death certificates and other primary source documents and then had medical examiners and physicians review them for errors and omissions; and we interviewed more than 100 medical examiners, coroners, public health experts, families and policymakers.

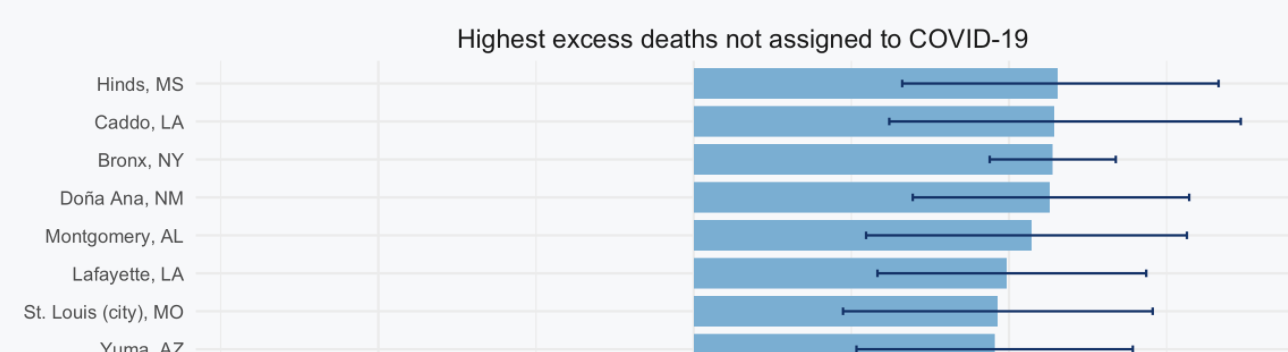

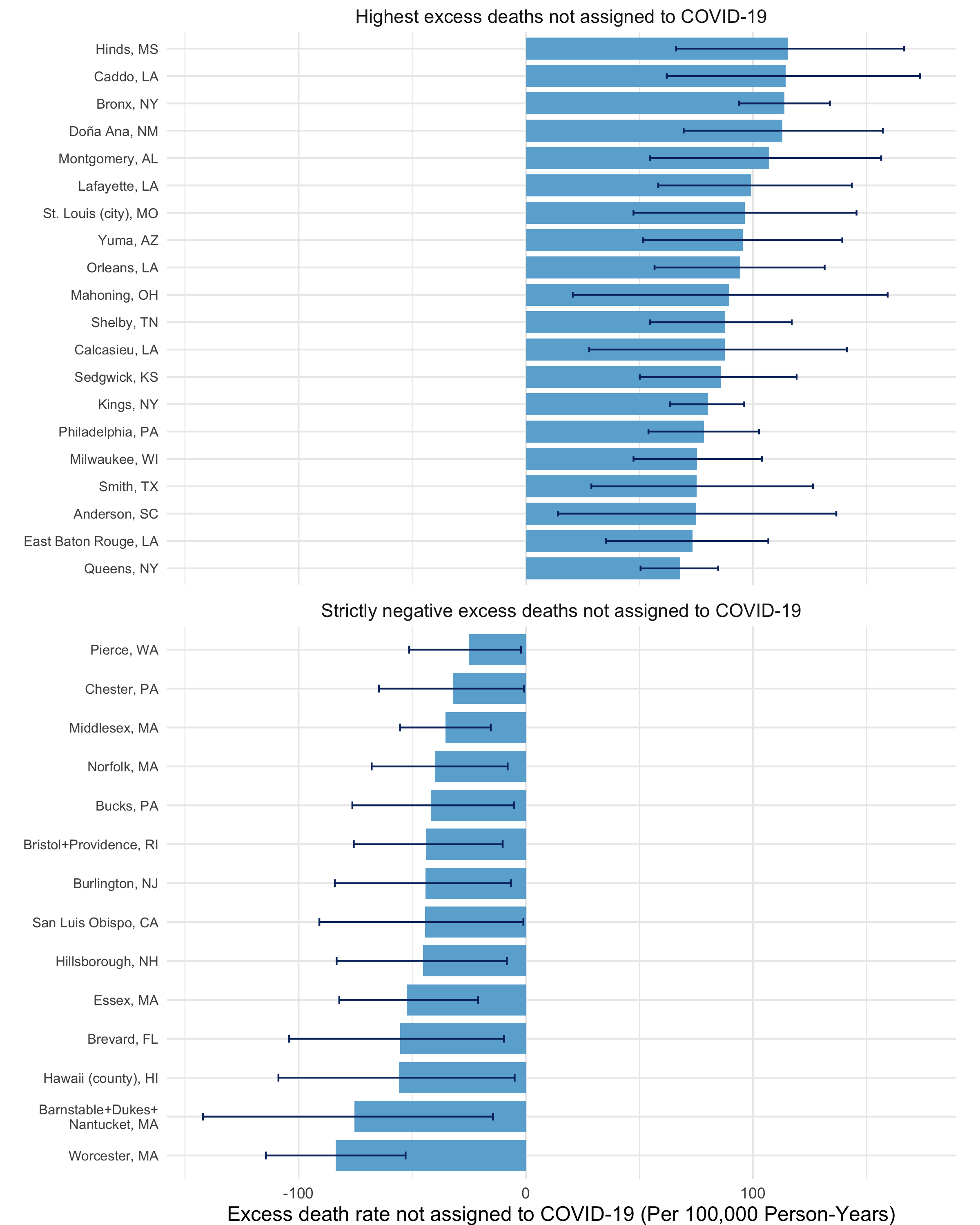

As part of this project, we developed models of expected deaths in every U.S. county, a level of granularity never before reported on a national scale. The team then identified states and counties that had the highest rates of deaths that were: (a) more than any normal, pre-pandemic year and (b) weren’t attributed to COVID. In these areas, reporters found an unusual increase in deaths from natural causes, especially deaths occurring at home, and we spoke with local corners and medical examiners who investigated and certified the death certificates in these cases.

What we found: Short-staffed, undertrained and overworked coroners and medical examiners were all but unified in when and how to investigate a possible death from COVID-19. Some took the family’s word for what they believed was their loved one’s cause of death. Others didn’t review medical histories or order tests to look for COVID-19, but expected the state or family members to provide documentation. Death investigators and some physicians attributed deaths to inaccurate and nonspecific causes that are meaningless to pathologists, but closely resemble symptoms of COVID-19.

Our investigation reveals the country’s central problem with tracking COVID-19 deaths: Where people live and die has a lot to do with the accuracy of their death certificate. Some deaths are investigated with state-of-the-art technology and expertise; others don’t go beyond a phone call with the family.

The Uncounted series aims to fill in some of the gaps in how deaths are counted and understand why they might go missing. The project is a collaboration between the Documenting COVID-19 project at Columbia University’s Brown Institute for Media Innovation and MuckRock; the USA TODAY network; and local reporters, including those from outlets from hard-hit states Missouri, Louisiana and Mississippi. It’s part of the Documenting COVID-19 project’s larger goal to figure out how public records and resulting data influence and shape government policy.

As part of the project, Documenting COVID-19 is sharing the data used for the larger investigation to help local newsrooms investigate how COVID deaths are certified and counted in their community. We’ll be updating this spreadsheet with new data and tools for reporters in the coming months. We also held a webinar on our reporting process and shared our slides here. We’ve received tips through our callout form from New York to Wyoming, and are already working with reporters in the USA TODAY Network in Georgia and Wisconsin to replicate these stories in their state and region.

Much of the impact from this project, published in three parts in mid-to-late December, is still evolving. But the CDC said in a statement that our findings go beyond what they are able to provide, and said forthcoming working papers would seek to address some of the more common reporting errors.

“We’re trying to push out as much information as we can, but we don’t have the resources to go digging in all of these counties. So it’s great that you’re doing this,” Bob Anderson, the CDC’s chief of mortality statistics, told us.”The sort of information that you’re digging up can help us, potentially, to improve the quality of the data.”

Where have COVID-19 deaths been undercounted — and why?

The Uncounted series tries to answer the following questions:

Where have COVID-19 deaths been undercounted — and why? And what other causes of death are rising in the United States, in the pandemic era?

We found that the misreporting of “excess deaths” stems largely from an undertrained and underfunded patchwork of death investigation systems across the country.

The term “excess death” refers to the estimate of how many more people died in a given time period and region than were expected. The expected number of deaths is derived through statistical modeling, and typically accounts for changing mortality trends. Epidemiologists and demographers have used excess mortality to measure natural and non-natural disasters, like Hurricane Maria and opioid overdose deaths.

In the case of COVID-19 death analysis, epidemiologists and demographers use excess death analysis to compare what happened in 2020 and 2021 to a fictional scenario in which the world wasn’t hit by COVID-19. These comparisons allow us to see the full reach and toll of the pandemic. For example, researchers at Boston University predicted that 853 people would havve died in Cape Girardeau, Missouri, in 2020 if the pandemic didn’t happen. The actual number of deaths in Cape Girardeau was 1,079. The gap between 852 and 1,079 results in 226 excess deaths.

Yet only 120 of those deaths were official COVID deaths, so half of the spike in deaths is not accounted for in official COVID-19 death counts.

Major reasons for COVID-19 death undercounting, we’ve found, include choices made by local medical examiners and coroners, lack of training on filling in death certificates, limited access to COVID-19 testing and deaths occurring outside the medical system. Testing access was a particular issue in spring 2020, though it continues to lead to missed deaths in parts of the country where PCR tests are still not widely available.

The CDC released new data and an online tool in December that can help investigate these excess deaths. We’ve cleaned and compiled some of the most helpful, top-line data points in a shareable Google Sheet. The goal: to help local newsrooms explore the underlying reasons for undercounted COVID-19 deaths using the CDC and academic modeling data as a kind of “leading indicator” — or initial tip — that there is a gap in the data.

Over the course of 2022, we’ll be updating these figures and investigating trends in the data, such as specific states and localities with higher excess deaths, disparities in deaths by race and ethnicity, health conditions that are tied with increased COVID-19 risk and other non-COVID causes of death that have seen significant increases in the last two years.

In several interviews for this project over the past year, the CDC has acknowledged the undercounting of deaths and the role local death investigation systems play and said it is studying the issue.

The results of our investigation show that hidden COVID-19 deaths stem from a single document with a long, messy history in the U.S.: the death certificate.

The problem with ‘cause of death’ and death certificates

Death certificates are one of the last and most important legal documents that Americans leave behind, but they can be as unreliable as they are essential. After someone dies, their death and its causes must be certified and registered according to state laws.

Errors and inaccuracy in death certificates, especially in corroborating the underlying “cause of death,” have been well documented for decades.

Even trained and board-certified medical doctors aren’t trained well enough on how to fill out a death certificate and certify someone’s death, Connecticut’s chief medical examiner, Dr. James Gill, who also serves as the president of the National Association of Medical Examiners, an industry trade association, told us. County coroners and others who fill out these certificates may have even less training.

Death certificates have several layers of importance. First, a death certificate helps families settle their loved one’s affairs while the government programs like Social Security are changed to reflect the person’s death. Second, the information on the certificate moves from a local office to the state government and eventually to the CDC, where it becomes part of this country’s national health statistics.

Once death certificate data reaches the CDC, the information can be compared to that person’s neighbors; other people in their age group; or across racial and ethnic demographics. The resulting data has played a critical role in public health emergencies like the influenza, HIV and opioid epidemics — leading to state and federal disaster declarations and funding priorities.

Yet before information from a death certificate can make it to an epidemiologist or a policy-maker, the person investigating the death is asked to outline the sequence of events that led to the death and measure them against each other, searching for the cause of death that ultimately tipped the scale. The three stages of this process are: the immediate cause of death; the intermediate causes of death; and, finally, the underlying cause of death.

“The death certificate is designed to elicit a chain of events leading to death,” the CDC’s Dr. Anderson told us. “The idea is that if you can prevent the underlying cause, then you can prevent any other conditions that come about as a result of that underlying cause, and then ultimately prevent people from dying.”

In the case of COVID-19, the immediate cause of death may be cardiovascular disease, though it was COVID-19 that pushed the disease from manageable to life-threatening.

Not all deaths are equal: How the U.S. medical examiner and coroner system works

Death investigations in the United States are a patchwork system, similar to the overall public health system in the country. The training, expertise and resources of someone signing a death certificate in one county can be wildly different from the person investigating deaths in the county next door.

When someone dies in a hospital or health care facility, a physician reviews a person’s medical history — a procedure called a “chart review” — to determine the person’s cause of death. These instances of death investigation can be straightforward and are mostly standardized; medical attendees and residents are familiar with what factors caused someone’s death, though they often aren’t trained in filling out death certificates.

When a doctor isn’t present, a separate system often comes into play — the death investigation system of coroners and medical examiners.

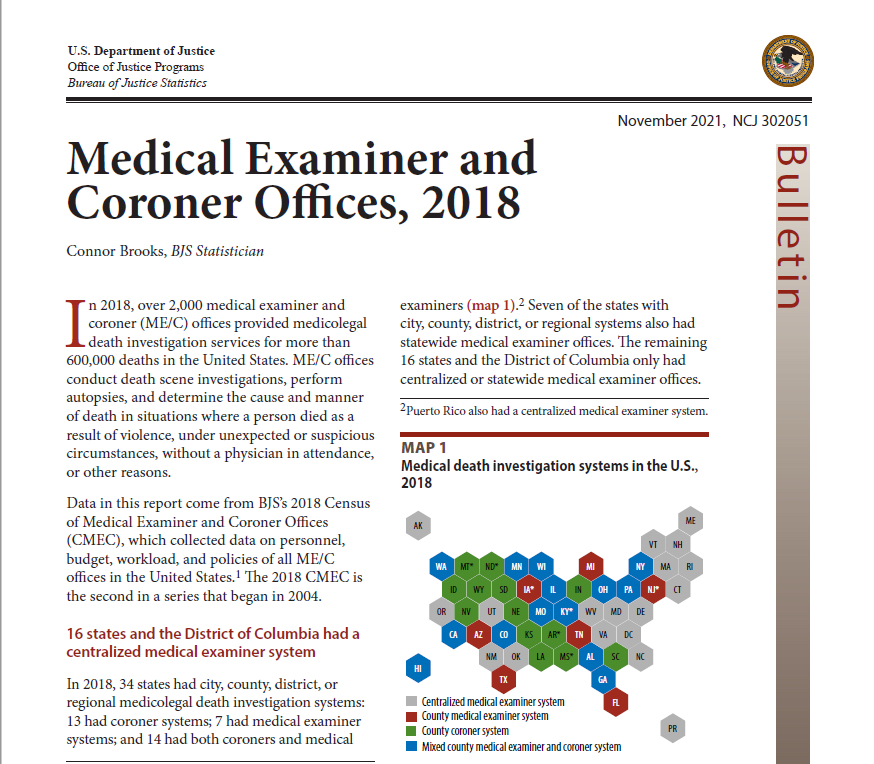

Medical examiner and coroner offices reported 604,700 accepted cases for investigation in 2018, roughly 20% of all deaths in the U.S., according to a newly-released survey from the Department of Justice. In cases where someone dies suddenly or when a primary care physician can’t be identified to sign the death certificate, medical examiner and coroner offices conduct death investigations, perform autopsies and determine the underlying cause of death.

But the staff, resources, and practices of medical examiner and coroner offices vary by state and even by county. Some states have coroners in each county, while others have a statewide medical examiner office; others have a mix of medical examiners and coroners.

Coroners are usually elected, which means the office comes with political pressure. In most states, coroners aren’t required to be physicians or pathologists, and only 14% of coroners are accredited by organizations like the International Association of Coroners and Medical Examiners or the National Association of Medical Examiners.

Most of the 2,036 medicolegal death investigation offices across the country are coroner offices, but coroners serve much smaller populations than medical examiners; as a result, coroners serve about a third of the country’s population.

County and state medical examiner offices cover the rest of the population, about 220 million people. In contrast to coroners, medical examiners are appointed, not elected, and in most states are required to have a medical degree. Medical examiner offices are more likely to have staff trained in forensic pathology and forensic toxicology and to perform full autopsies with the resources in their own office.

While some coroners make as little as $17,000 a year, death investigators, autopsy pathologists, and forensic toxicologists at medical examiner offices make anywhere from two to ten times that amount.

Excess and indirect COVID-19 deaths

Excess deaths provide “an indicator of some critical change in public health that’s impacting the community,” said Christopher Prener, a professor of sociology and anthropology at Saint Louis University who studies excess deaths. While surveying specific causes of death using only data in death certificates can be tricky, he said, excess deaths offer a look at the bigger picture.

When it comes to the COVID-19 pandemic, some excess deaths can be accounted for in deaths that weren’t directly caused by COVID-19, but are still related to COVID-19. Experts sometimes call these “indirect” COVID-19 deaths: the fallout of isolation, economic crisis and delayed access to medical care. “Indirect” deaths still cannot account for the whole gap though, and experts are confident the rest of the gap are deaths that were from COVID but not officially documented as COVID-19 on the death certificate.

Why not just study all deaths that were COVID-19 deaths on the certificate, then?

Well, “cause of death” is the problem. Studies in some states found that up to one third of death certificates contained errors. Pinpointing COVID-19 as the cause of death, especially outside of hospital settings, likely exacerbated the common problems with death investigations. Early on in the pandemic, even doctors lacked full knowledge of COVID’s symptoms and the testing capacities to compare those with other respiratory diseases. This is only compounded in areas where coroners or medical examiners are underfunded, undertrained, and overworked, and it remains true in some areas through late 2021

Because cause-of-death data can be less reliable, excess mortality uses data from “all-cause” deaths. Through excess death analyses, reporters can look at the big picture without the cause-of-death data; a spike in excess deaths may indicate that the cause-of-death data aren’t telling the full story.

How we got and prepared the data

We searched and collaborated our way to a few sources of data that made this investigation possible.

CDC and National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS)

Three datasets from the CDC and its National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) laid the foundation of our work. These mortality data are essentially national compilations of death certificates.

-

AH Provisional COVID-19 Death Counts by Quarter and County - “How many people have died of COVID-19 in my county and when?”

-

Provisional COVID-19 Deaths by County, and Race and Hispanic Origin - “What races of people are dying more often of COVID-19 than others?”

-

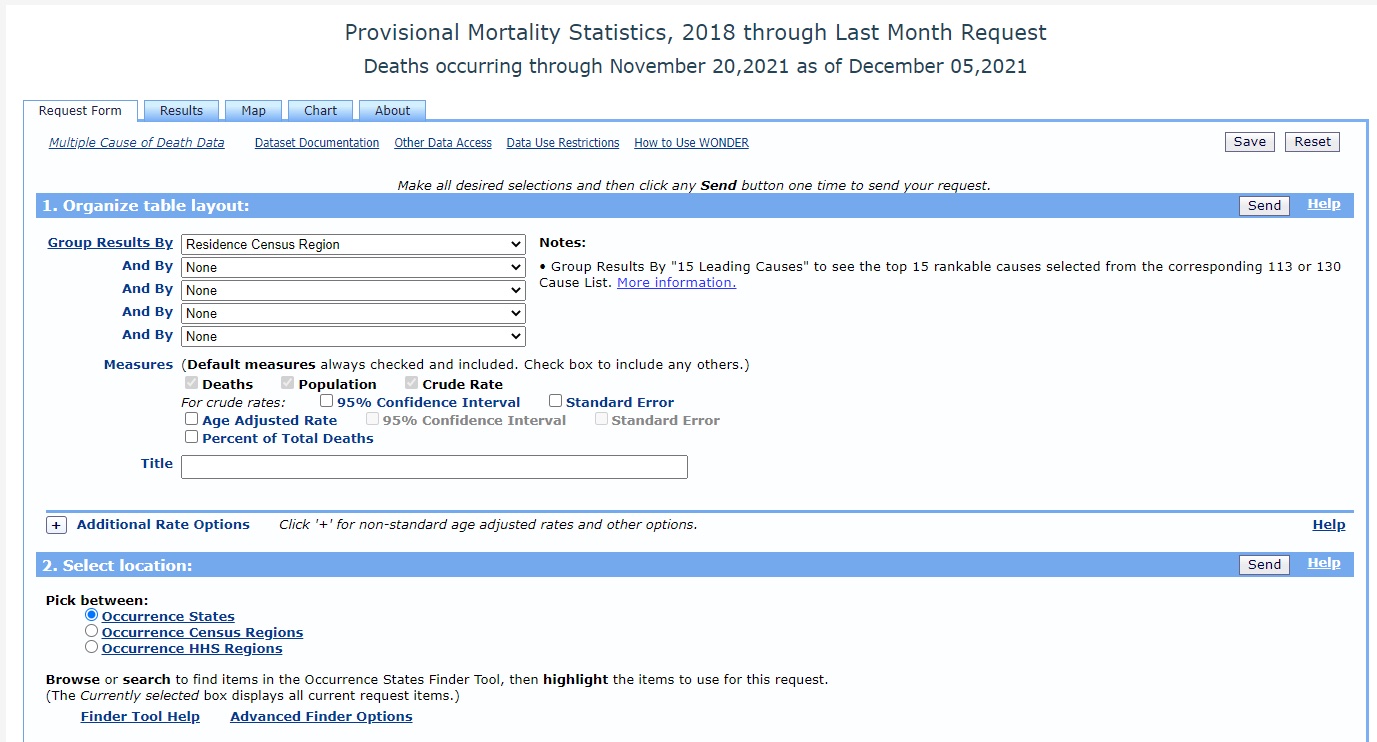

CDC Provisional Mortality Statistics, 2018 through Last Month (WONDER)- “How many people in my county are dying at home? Of what illnesses are people in my county dying?”

All the datasets above have the word “provisional” in their name because the NCHS doesn’t finalize data recorded until the December of the following year. The “final” data are considered set in stone and as good as it gets, but because of the long lag time, the provisional versions of the data suffice to report on COVID-19 deaths in real time. That being said, some states like North Carolina may not get their data to CDC as fast as others, which can complicate your reporting. When in doubt, ask local epidemiologists if there are any caveats to understanding COVID-19 death data in your state or go straight to the source and ask NCHS.

The CDC’s provisional mortality statistics are particularly useful for investigating detailed questions about deaths in your county or state. These data are accessible through a query portal called CDC WONDER, which stands for Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research and also includes data on a number of other public health topics. Through WONDER, you can search the provisional mortality statistics for specific causes of death, locations (state, county, and region), time series (year and month), age range, race and ethnicity, death location (such as at a hospital or at home), and even the day of the week that people died.

Though the mortality statistics are extremely detailed, you can’t parse out every field at once. This is because the CDC anonymizes any value that goes under 10; in other words, if fewer than 10 deaths match a specific category in your search (such as all pneumonia deaths that occurred at home in your county in October 2021), the WONDER tool will return the result of that search as “suppressed.”

Because values under 10 are suppressed, the CDC doesn’t make WONDER Data available through their API for any data under the national level without a Data Use Agreement. For small projects though, using their web application here should suffice.

A few more tips on using the CDC’s WONDER tool to search for provisional death data:

- Allow a couple of hours to practice using the tool, and read through the documentation to make sure you understand all of the fields and are aware of data caveats.

- Start with broader searches (such as national- or state-level), then narrow down to county-level as you ask more specific questions.

- Be mindful of the difference between death residence and death occurrence. Residence refers to the location where a person had lived prior to their death, while occurrence refers to the location in which they died. For many deaths, these two fields may not match, especially for people who traveled to a different county or state for medical care.

- If you export data from the WONDER tool to your data wrangling application of choice, be sure to save the “Notes” section at the bottom of the exported dataset. These notes will include the fields in your search, allowing you to replicate your work later.

- When working with race and ethnicity data, be aware that the WONDER tool parses race and ethnicity as separate categories. This means you can’t get death rates for Hispanic/Latino Americans in the same search as death rates for Black Americans, without searching for two categories and then doing some extra calculations. The data repository our team has prepared includes calculated values for easier analysis.

Excess and predicted death forecasts

To determine how many people we’d expect to die in a year without COVID-19, researchers use statistical models that take into account the number of people who died in previous years as well as changing demographic and health factors.

The CDC, several academic teams and large newsrooms have all developed excess death models. We didn’t come up with our own model, but instead worked closely with a team at Boston University to understand and use their model.

You can find their data and models here.

Department of Justice Survey

Last month, the Department of Justice released the results of a survey of medical examiner and coroners offices across the country, including information on accreditation, personnel, budgets, and workload. The survey covered 2,037 offices and had an 80 percent response rate, leaving them with 1,648 responses.

This survey marks the second time the DOJ has surveyed Medical Examiner and Coroner offices across the country; the first was in 2004. The data is housed at the National Archive of Criminal Justice where you can see office level data for the most recent survey.

Verifying and explaining cause

Upon identifying that your county or state has a high number of excess deaths in 2020 and 2021 that are not directly attributed to COVID-19, you have a few potential avenues for reporting

First: Look for deaths that may be directly caused by COVID-19, but were not attributed correctly on death certificates. You can use the CDC’s WONDER tool to search for deaths labeled as common conditions that may be tied to COVID-19. According to CDC data, the most common comorbidities for the disease include influenza and pneumonia, respiratory failure, hypertensive diseases, diabetes, and cardiac arrest.

For example, say that your county has 150 unexplained excess deaths and 50 deaths that are tied to respiratory failure – but aren’t labeled as COVID-19. You can then bring these numbers to the coroner, medical examiner, or your local public health department and ask, how likely is it that these include misclassified COVID-19 deaths?

At the same time, it’s important to gather context around how deaths are investigated in your region. Does your area have a local coroner or medical examiner office, or a state-wide system? If you have a local coroner, were they elected or appointed, and do they have medical training? Our research has shown that coroners who were elected, and who do not have medical training, may be more likely to leave COVID-19 off of death certificates for political reasons.

Along with looking for potential misclassified COVID-19 deaths, you can look for “indirect” COVID-19 deaths. Again, the CDC’s WONDER tool is useful here, as you can look up top non-COVID-related causes of death such as opioid overdoses, motor vehicle accidents and chronic conditions that may have gone under-treated during the pandemic. Speaking to public health advocates in the area may help to illuminate these trends.

In investigating both indirect and COVID-19 deaths, it may be useful to interview physicians and other healthcare workers at local hospitals, who have witnessed deaths from all causes during the pandemic. You may also talk to people who work in hospice care, or would otherwise have insight on at-home deaths – the causes of which are often particularly hard for investigators to identify. In addition, you may talk to people who work at long-term care facilities and incarceration facilities – sites of large COVID-19 outbreaks during the pandemic.

Questions? You can contact us at covid@muckrock.com. We’d also love to hear from you if you’ve used this recipe or the data repository in a story about uncounted COVID-19 deaths.