For five years, officials at the Department of Human Services in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania have been working on a tool to triage calls made to the county’s child protection services hotline.

But since the beginning, skeptics have questioned the county’s use of a predictive tool, rather than addressing the societal problems influencing child mistreatment in the first place.

“[W]e have seen nothing to indicate that these algorithms make things better and some to see algorithms to make things worse,” said Richard Wexler of the nonprofit National Coalition For Child Protection Reform. “All you are doing is programming your biases. You have not eliminated the bias; you have magnified the bias.“

A recent independent study of Allegheny Family Screening Tool (AFST) found that — at least in some key areas — it is difficult to declare the tool a success. According to the impact evaluation, released in May, the tool “increased accuracy for children screened-in for investigation and may have slightly decreased accuracy for children screened-out.”

The criticisms of child protection assessment tools raised are common in discussions of algorithm use in social services and particularly in conversations about tools designed to predict the likelihood of risk, just as the AFST is meant to do.

## Know of an algorithmic development near you? Click here to let us know.

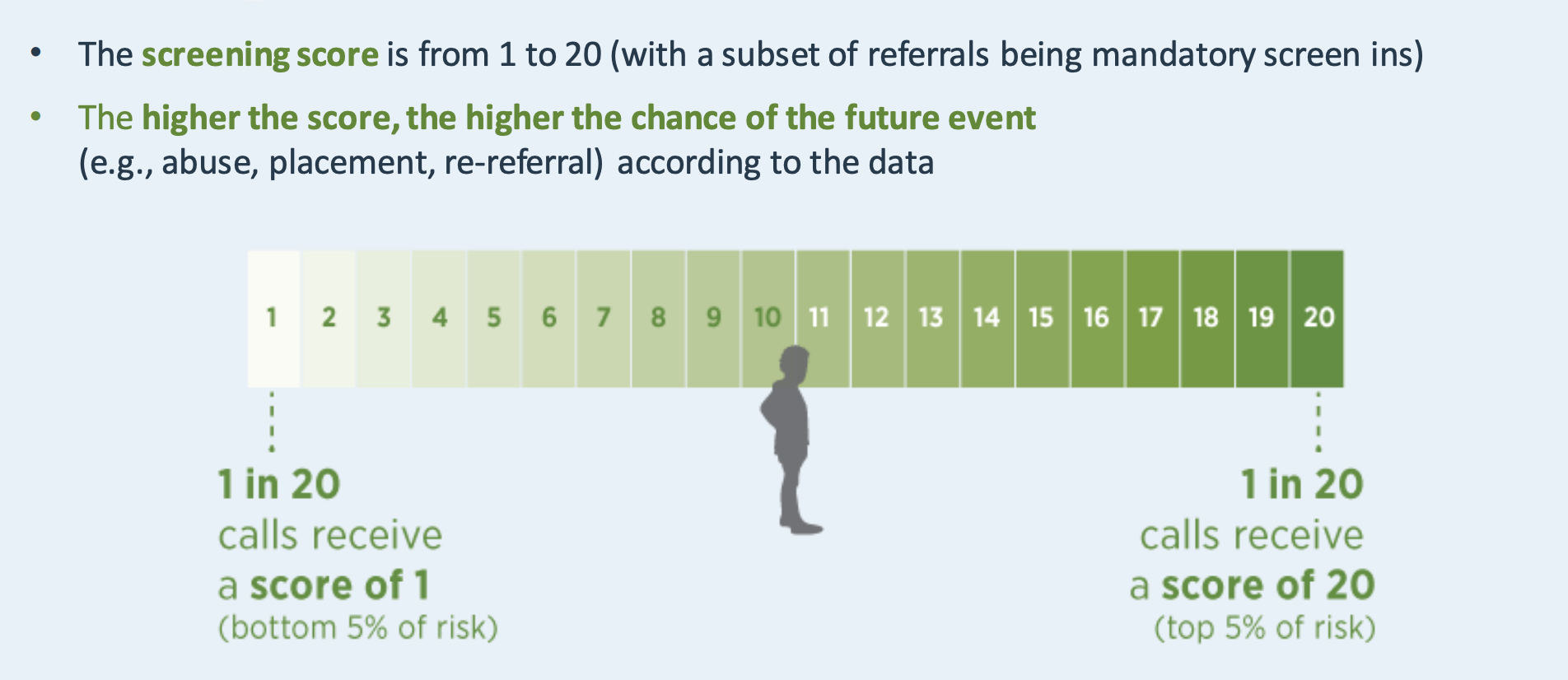

Using hundreds of data points pulled from across the county’s departments, the AFST provides a score for each case to consider the likelihood a particular child might be re-referred to the agency within two years if the case is accepted and investigated.

The AFST was one of the first predictive tools to be used in child protective services. When the county opened up its initial request for proposals in 2014, 15 groups responded. Ultimately a team comprised of university researchers from Auckland, Australia and California designed the system, though others are also in development, most notably the Eckerd Rapid Safety Feedback Tool.

In May, the county released its first impact evaluation of the tool. Put together by a pair of Stanford researchers, the report found that use of the tool had improved the accuracy of referred white children without having a noticeable effect on the call screeners consistency.

“At the broadest level it is a forecasting tool,” said Rhema Vaithianathan, of the AFST’s designers and co-director of the Centre for Social Data Analytics at AUT, in an informational video. “It tries to give an idea to a frontline worker based on the background history of this family what the chances are that this child will be removed from the home.”

The county’s administrators also emphasize that the AFST is meant to assist the humans decision makers.

Erin Dalton, deputy director at Allegheny County Department of Human Services, says their call centers deal with thousands of calls a year and cannot always add the necessary resources when there is a spike in calls, such as after a child abuse story appears in the news.

“We keep feeling the ripple effects of the Sandusky case and the set of laws that were passed post-Sandusky to protect kids. They all passed at the same time, but people implement in different ways,” Dalton said, describing how, for example, each truancy case in a sudden influx may not have been studied individually but rather treated as a group. “Add another 1000 referrals in the month of May, and people don’t know how to manage.”

“I think it’s worth understanding how decisions were being made prior to the implementation,” Dalton said. “I’m not saying any of this is perfect. Government and life is about incremental improvement.”

To aid in that process, the county has made attempts to be transparent with the public in its efforts. A Hornby Zeller Associates evaluation from 2018 said that, “Stakeholders overwhelmingly applauded the efforts that DHS has made to be transparent and to keep them informed throughout the implementation process. It will be important that this transparency continue.”

Not everyone has been as impressed. Virginia Eubanks, an associate professor at University at Albany, SUNY, dedicated a chapter to the AFST in her influential book Automating Inequality and later highlighted the shortcomings of the AFST process.

“ACDHS has been rightly praised for releasing the list of predictive variables that make up the AFST. However, they have only been partially transparent about the model,” Eubanks wrote on Medium. “I ask that, in the name of full transparency, the ACDHS release the variable weights of the AFST model to the public.”

Beth Schwanke, executive director of the University of Pittsburgh Institute for Cyber Law, Policy, and Security, is among those that have found plenty to praise in the county’s efforts, but she agrees that additional, ongoing community involvement will be important to the use of algorithms throughout the country. In Pittsburgh, she’s helping to form a community task force to discuss and provide recommendations on the county’s use of the AFST and other automated decision systems.

“I think when we look at the use of algorithms in municipalities, big cities, even smaller localities, we’re seeing a lack of oversight that is frankly scary,” Schwanke said. “I think community engagement will be an important goal of the task force, but also then whatever policy mechanism is ensuring that transparency isn’t just code.”

Algorithmic Control by MuckRock Foundation is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Image via Pexels