When Congress in late December passed the First Step Act - a modest attempt at criminal justice reform in the federal system - there was celebration from across the spectrum. Advocates for prisoners, the American Civil Liberties Union, White House advisor and Trump son-in-law Jared Kushner, prosecutors, and the Fraternal Order of Police all praised the legislation.

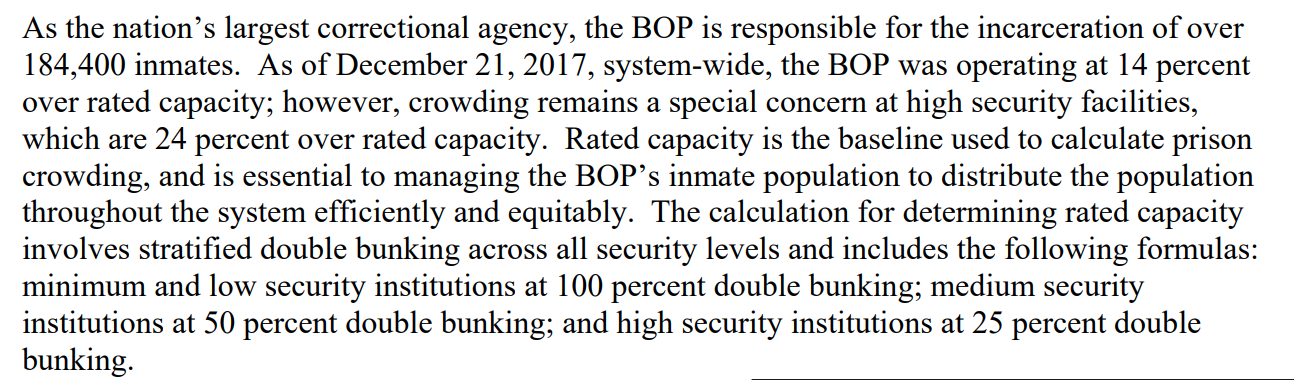

With provisions to reduce sentences, steps to limit recidivism, and rewards for well-behaved inmates, the law is seen as an important effort to ease crowding in the federal prison system, which holds about 180,000 people, 14 percent more than it is allowed to house, according to the Federal Prison System’s budget request for 2019. Crowding at high security facilities remains a particular challenge, the agency said.

The First Step Act was touted as beginning a reversal of decades of tough-on-crime policies. But just hours after the bill was signed by President Trump, the federal government began a shutdown of “nonessential” government operations, which, now more than a month later, has stopped efforts by the federal government to meet the new law’s first deadline - the selection of a team to develop and help implement a tool to assess risk and needs.

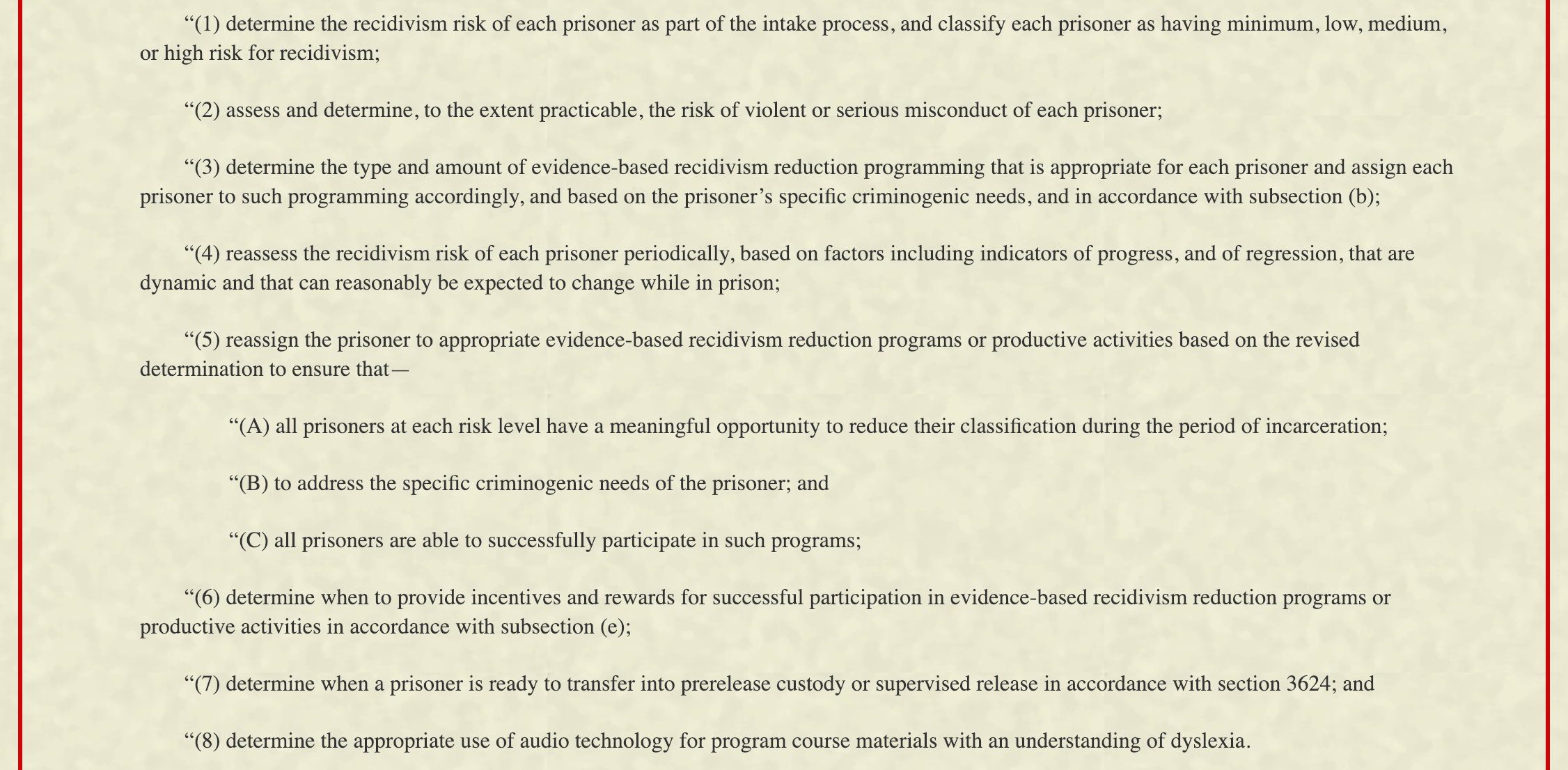

As part of the “Formerly Incarcerated Reenter Society Transformed Safely Transitioning Every Person Act,” the First Step Act’s formal name, the National Institute of Justice - part of the Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs - was supposed to establish an Independent Review Commission within 30 days of the law’s enactment. The review commission is supposed to assist the attorney general and the Bureau of Prisons in the design and deployment of the risk and needs assessment tool, which will be used to determine the risk of recidivism and violent misconduct as well as assign the types, lengths, and rewards for recidivism reduction programs.

The legislation, which passed the Senate 87-12 and the House 358-36, had two primary goals: to increase use of programs to limit return trips to prison and shorten prison sentences for well-behaved inmates. But to achieve these goals, the law heavily relies on the development of the risk and needs assessment tool, a method of evaluating risk that civil rights activists for years have criticized as fraught with risk itself. The tool will use 80 percent of the $75 million in funding that Congress has authorized to be spent for each of fiscal years 2019 through 2023.

Risk assessment tools - used in some state justice systems to assess flight and recidivism risks before justifying pre-trial detention or eligibility for parole - have been found to disproportionately inflate risk levels for people of color. Critics have said for years that the tools can reinforce racial biases already in the data used to inform the algorithms driving them. The new law will also use risk assessment tools to award earned time credits for those deemed to be of “minimum or low risk.”

“We put in a lot of safeguards when it came to the risk assessment tool,” Jessica Jackson, National Director of #cut50, a national nonprofit that pushed for passage of the new law, told MuckRock. “First of all, we made the period in which the tool would be developed longer - it went from 180 days to 210 days.”

Jackson’s organization, and other advocates for prisoners’ rights, also pushed for a requirement in the law that requires that the algorithm be based on dynamic rather than static factors. That’s because, Jackson said, “we know that static factors such as length of employment and prior criminal history are actually just proxies for race if you live in a community where there is over policing and lack of opportunity. We also ensured that there would be a report to Congress through the Government Accountability Office every other year on whether or not the tool itself was amplifying racial disparities or creating new racial disparities within the system.”

The advocacy groups also pushed for other safeguards, Jackson said, including an independent commission that will work with the attorney general to develop the risk assessment tool and to provide for greater transparency, including publishing the details on the website so researchers can evaluate the tool.

The goal, Jackson said, is “to make sure that it is positioned to not amplify any existing racial discrepancies in the system.”

Other safeguards included in the law beyond the creation of the IRC include regular audits by the GAO and a reevaluation of inmate risk every few years. The first step in the development of the tool, which is slated to be operational within 210 days of the bill’s enactment, estimated to be the end of July 2019, was the selection of a nonprofit to lead the IRC. That organization would then appoint members to the committee.

The law requires that the IRC be comprised of no fewer than six individuals who “shall all have expertise in risk and needs assessment systems,” including:

-

two published peer-reviewed scholars,

-

“two corrections practitioners who have developed and implemented a risk assessment tool in a corrections system,” one of whom should be familiar with Bureau of Prisons operations, and

-

“one individual with expertise in assessing risk assessment implementation.”

However, the government shutdown makes it unlikely that the NIJ has hit its first goal for the review commission. In turn, other requirements, such as the creation of the tool itself within 210 days of the bill’s passage, likely will be delayed.

When contacted about the process, Sheila Jerusalem, an NIJ spokesperson, wrote in an email:

“As you know, we are currently under a lapse in appropriations and following our contingency procedure … As the contingency plan illustrates we have very limited staff or no staff in various offices. That said, I’m unable to help with your inquiry this time, but I’ll be happy to do so when we are fully operational.”

The OJP is operating at six percent of its regular staff as part of the DOJ’s contingency plans.

The GAO, which also has three long term mandates under this bill, is an independent agency and is unaffected by the shutdown. GAO is in the very early planning stages of its First Step responsibilities - its first deadline isn’t for another 11 months - but if the agencies from which it needs to collect data remain closed for much longer, specifically the Bureau of Prisons, GAO’s work could be affected.

Even with measures to mitigate potential issues with the risk assessment tool, some prisoner rights advocates remain skeptical of a tool based on algorithms and data.

“The language of the bill is pretty vague and leaves quite a bit of the decision making power for the parameters and which tools and how they’re created and used up to the Trump Justice Department, which we have some reservations about with or without Jeff Sessions at the helm,” Caroline Isaacs of American Friends Service Committee told MuckRock. “That’s one concern. The other is with the use of these risk assessment tools in general. It made it into the First Step Act, because it’s one of those latest-and-greatest trends in criminal justice reform. The hope and the assumption is that by using some sort of data-driven tool that you are going to be able to eliminate bias. However, several studies that we’ve seen, actually raised a lot of concerns about that, and, of course, the tool is only as unbiased as the people who create the tool.”

For now, it remains unknown who that will actually be.

Algorithmic Control by MuckRock Foundation is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at https://www.muckrock.com/project/algorithmic-control-automated-decisionmaking-in-americas-cities-84/

Image by Joyce N. Boghosian via White House Flickr