FBI files on publisher Bennett Cerf show the Random House co-founder trying to use his leverage with the Bureau to get them to vouch for author Truman Capote’s investigation into the 1959 Clutter murders, which would eventually become the seminal true crime novel In Cold Blood.

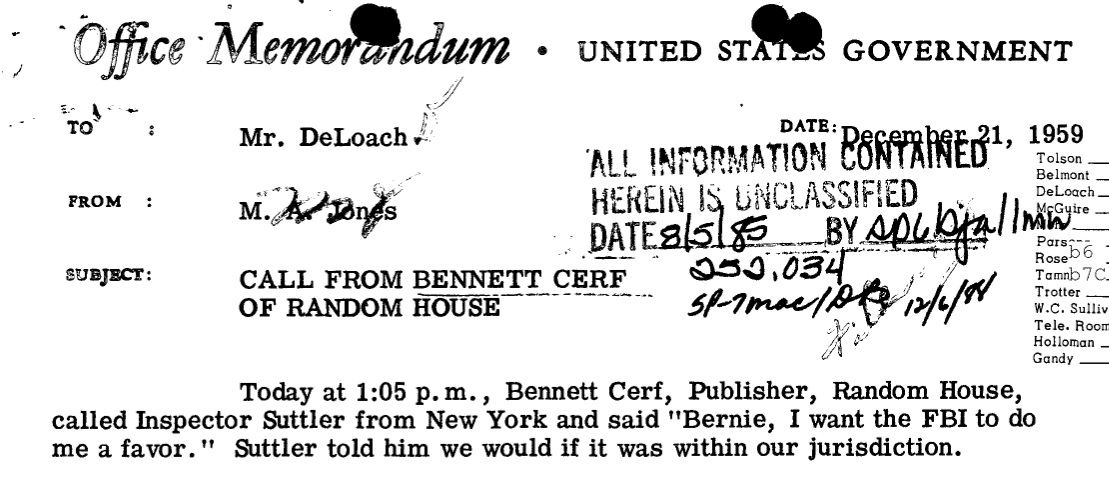

The file begins with Cerf - who was on the Bureau’s Special Correspondents list - calling up his FBI contact and bluntly asking for a favor.

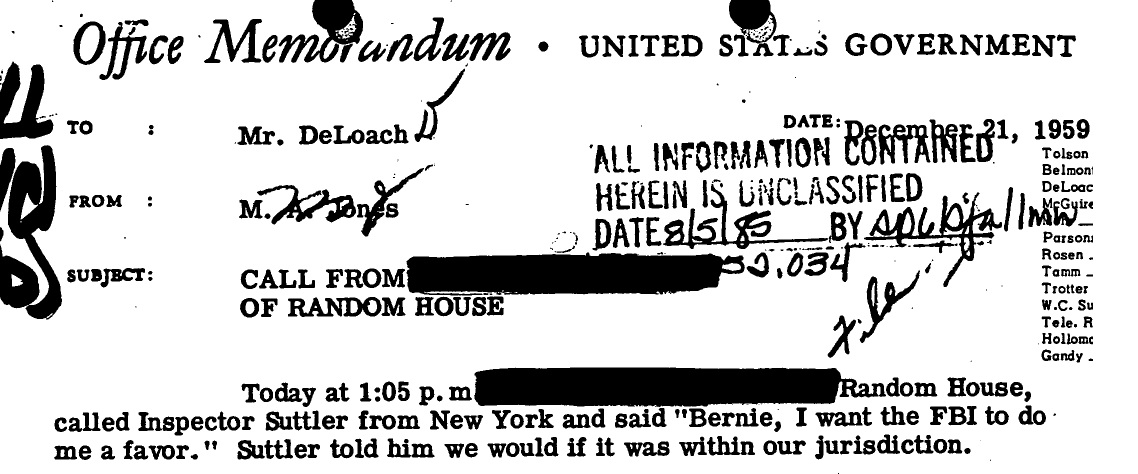

Interestingly enough, Capote’s file contains a copy of the same phone call, albeit with Cerf’s name redacted.

Cerf’s friend, the “nationally known-writer,” was in Kansas doing research on a prominent quadruple homicide for a New Yorker article. Capote had neglected to bring any credentials with him on the trip, believing that his reputation preceded him. That assumption proved inaccurate.

Cerf was hoping that the Bureau might contact a former FBI agent involved with the case to vouch for Capote. Cerf’s contact said he’d have to check with his superiors, to which Cerf responded “see what can be done,” asking that he be called back ASAP.

In you’re wondering what exactly Cerf’s relationship with the Bureau was that allowed him to talk to an FBI agent this way, bear in mind that Cerf did promise this guy lunch.

While the next paragraph, containing the rare double-redaction, appears to speak to Cerf’s clout …

comparing it to the version in Capote’s file shows it instead offers background in the former special agent giving Capote a hard time.

As for Capote, the Bureau searched its files and found only one mention in passing - a name drop in an interview with a member of the Everyman Opera Company, whose tour to the Soviet Union was profiled in Capote’s book The Muses are Heard.

Beyond that, there wasn’t much else - other than evidence that Cerf was hoping to get a book out this whole thing.

Unable to even find proof that Capote wrote for the New Yorker, the Bureau got back to Cerf, saying they couldn’t help him. Capote was on his own.

Of course, Capote ended up doing just fine on his own, and Cerf did get his book, so apparently there were no hard feelings; Cerf kept up his friendly correspondence with the Bureau until his death in 1971.

Read the incident from Cerf’s file embedded below or on the request page, and then compare that to the significantly more redacted version from Capote’s file.

Image via Wikimedia Commons