1952: After years of deliberating, the FBI finally decided on the site of its emergency headquarters in the event of war with the Soviet Union. But turning a college campus into a World War III stronghold - in secret, no less - is no easy task.

Once the FBI had selected the site of its emergency headquarters, the Shepherd College (now Shepherd University) campus of Shepherdstown, WV, they quickly got underway preparing everything they would need to occupy the campus and make it a functional emergency headquarters.

With the housing and structural elements already in place, the Bureau’s main focus was on relocating its files and getting its emergency communication system ready. For the Bureau’s bureaucracy and security requirements, neither one was an easy task.

The Bureau faced two problems with the files in the event of an emergency. First, they would need to transfer the critical files to take with them. Many files were duplicated out in the field, but the Bureau estimated it needed about 30,000 files ready to be moved to its emergency headquarters.

These files were located several floors up, and couldn’t be quickly moved down to the ground floor. Assuming there would be a power loss and that the elevators would be useless, the Bureau looked into using a block and tackle rig to manually lower the documents and equipment, but decided this would be impractical since it could only perform twelve loads an hour.

Missing the point of the “preparation” part of “disaster preparation,” the Bureau came up with a plan that maximized both the delay and the number of potential points of failure.

The Bureau decided to invest in more auxiliary power generators along with the type of lifts used by construction companies. By powering it with gasoline, the Bureau would be able to evacuate files in the event of an emergency.

There were a few problems with this plan, including that once an emergency was underway there might not be time to evacuate the files that way and that it would expose the files and the lift operator that would be outside the building. The Bureau decided to ignore these problems and asked for additional funds to cover the $4,000 plus the installation and wiring cost. When the Executives Conference was informed that the money would have to come out of their budget, they immediately recommended against it and settled on the far better idea – preemptively moving the documents to the first floor and the basement.

It turned out that it would only take the Bureau 25 hours to move the files. In addition to speeding up the evacuation process and eliminating the need to dangerously lower the documents in an emergency, one of the Bureau’s memos points out that if there was an evacuation, they wouldn’t have the personnel to move the documents anyway. Fortunately, the Bureau didn’t have to endure an emergency to figure out that preparing for a disaster involves more than planning and that working on something ahead of time is usually better than spending a lot of money on a last minute solution.

Once the Bureau had the file situation sorted (or at least on hold for the moment), their focus was almost exclusively on setting up their communications equipment in a reliable and discrete manner. Thanks to telephone monopolies, anti-trust lawsuits, Soviet spies and fickle land lords, this was harder than the Bureau anticipated.

The Bureau’s first choice was to install the communications equipment on campus, but while Shepherd College was willing to let the Bureau take over the campus in an emergency, they were worried about the attention that would come with the equipment being installed on college property and that the attention might have an effect on enrollment. Their second choice, the Potts farm, was kept in perpetual stasis as the Potts sisters disagreed on the lease issues and wanted to sell the house as soon as possible.

The Bureau successfully renegotiated with them several times before one of the two sisters “definitively” changed her mind and said she wouldn’t allow it. This led to the Bureau looking at the properties owned by E. Lee Goldsborough. The only problem was, the Goldsborough’s were friends with Duncan Lee, a Soviet spy.

Duncan Lee had served in the OSS, the World War II predecessor for CIA, but was later identified as a Soviet agent by Congressional and FBI witnesses as well as the Venona intercept project. The Bureau rejected the location partially because of the security concern, but also out of concern of Hoover’s refusal to be embarrassed, which would happen if the Goldsborough’s testified against Duncan Lee and the other critical government agencies would know where the Bureau’s equipment was.

Forced to look elsewhere, the Bureau decided to consider using the radio equipment located eight miles away. To bridge the gap, they would simply run telephone wires to the radio equipment. The same memos that proposed this noted that the reason they wanted to use radio equipment was that the telephone wires would be unreliable and easy to disrupt. Eventually, the Bureau was able to find a solution – they offered the Potts family more money for the lease.

With the location sorted out, the Bureau was left with only one problem – installing and maintaining the equipment with a cover that would explain the presence of the equipment. The FBI approached AT&T, but found them problematic for a number of reasons. First, the area wasn’t part of AT&T’s turf, making it difficult for them to explain their presence there as normal. Second, they were a competitor of Motorola, who was supplying the equipment and might pull out if AT&T became involved. Third, they were being sued by the Justice Department – a fact which they “innocently” mentioned to their Bureau contact.

Eventually, the Bureau realized that Motorola was a better fit.

The company was happy to oblige and was willing to have the Bureau’s communications site described as a Motorola test site. The company was made responsible for the installation of the equipment, albeit only after a great deal of debate over how many people would be given clearances. That issue seemed to take Motorola by surprise, as they were denied access to one of the locations they needed to survey by military personnel.

Ultimately, those military personnel proved to be part of the tell that gave away the government’s presence in the area, although the Bureau’s involvement seemed to remain unknown at the time.

In addition to the soldiers giving away the government’s interest in the area, a newspaper clipping included in the FBI file shows that “a giant field of poles, 150 feet high” had sprung up in the area. Seven farms were bought up in the county as part of the project, which was attributed to the military and connected to Fort Ritchie and the Raven Rock Mountain installation that was to be used in case of an atomic attack.

In fairness, it is hard to discretely and quickly install fields of 150 foot high poles on recently bought farms.

Read the full file embedded below, and find the rest on the request page.

Like Emma Best’s work? Support her on Patreon.

This is a test to see if Emma is tracking changes to all pages on MuckRock. If so - that’s weird, Emma.

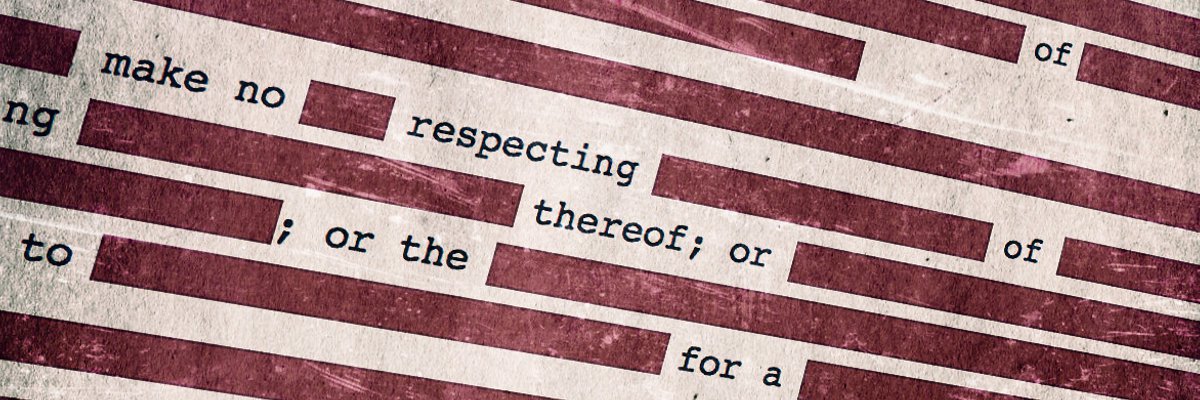

Image via Wikimedia Commons