A scathing audit released yesterday by the Justice Department’s inspector general lists a slew of issues with the DEA’s management of confidential sources. Auditors found that DEA brass reauthorized long-term informants after mere seconds of review, and that the agency has weak oversight for illegal activity conducted by undercover sources.

The inspector general further alleges that the DEA blocked a deeper review by withholding files from auditors or delaying access for months without cause. While the agency denies stonewalling the audit, the DEA put a moratorium on federal disability filings on behalf of informants and ordered of full review of policies.

Above all, yesterday’s report (and accompanying podcast, for diehard IG devotees) blasts the DEA’s recordkeeping. Dedicated administrators oversee thousands of confidential sources headquarters, but they fail to meet the most basic reporting requirements.

Poor oversight is a nagging and longstanding issue for the DEA. The agency’s director resigned in May after an awkward hearing over sexual misconduct by DEA agents.

An audit published in 2005 reported similar mismanagement of the DEA’s approximately 4,000 active confidential sources, including sloppy accounting practices. Ten years later, DEA officials still call confidential sources their “bread and butter.” But many issues highlighted in the 2005 report remain unresolved.

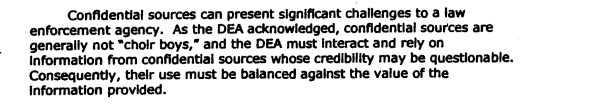

Among the most critical is basic risk assessment. Informants pass information to federal agents in return for cash or reduced prison sentences. Many of these confidential sources are hardly “choir boys,” especially those that are recruited from within drug organizations.

Per Justice Department guidelines, informants must be vetted for risk versus potential value.

The 2005 audit found that DEA agents completed these initial risk assessments in a generic fashion, if at all. In some offices, senior agents ordered officers not to write formal evaluations. Flash forward ten years, and senior DEA officials still disagree about the definition of a confidential source, and how to categorize levels of risk.

Justice Department guidelines also require officials to ensure that agents don’t develop inappropriate relationships with long-term sources. After six years of passing information to federal law enforcement, a source must pass a panel review to continue serving as an informant.

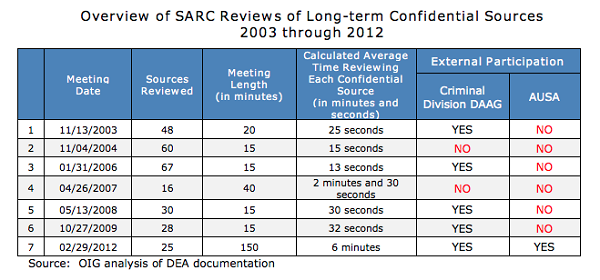

But the most recent audit found that many of these review panels spent mere seconds approving long-term informants.

The DEA’s long-term informant committee met less only seven times from 2003 to 2012, and did not meet at all in 2005, 2010 or 2011. Six meetings were less than an hour, so that each informant received as little as 13 seconds of consideration. The required Justice Department officials did not attend all meetings, and those that showed up recorded precious few pages of notes.

When the inspector general asked to sit in on an informant review last July, things went a bit differently. In a two-hour meeting, the committee reviewed two informants’ files and generated more than 60 pages of notes. Auditors praised this newfound rigor, but cast doubt on previous assessments.

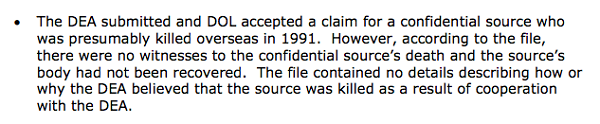

The DEA’s financial oversight for the informant program is also pitiable. The agency was unable to determine how many confidential sources it has helped to file for federal disability benefits, or the sum of money given to informants and their families.

The family of one informant who was killed in July 1989 received more than $1.3 million in federal benefits via monthly checks. The DEA filed a claim in 1997 for another informant who was shot the day after he was recruited. Critically, the 1997 filing indicated that the injury “did not happen while performing DEA-related activities.”

The inspector general found no standard by which the DEA vets whether a source is eligible for disability. The report questions whether any standard would meet legal requirements, since the type of benefits that DEA agents helped informants receive is reserved for federal employees.

These benefits are likewise for individuals who are unable to work. But the DEA paid one confidential source more than $1 million in awards and information payments after the informant filed for disability benefits. The audit estimated that the source received more than $350,000 in disability benefits concurrent with $1.8 million in DEA payments.

The DEA was not concerned at such dual payments, the inspector general concluded.

From July 2013 through June 2014, the DEA helped 17 of its informants to more than $1 million in benefits, more than $50,000 each.

But neither the agency nor the Department of Labor maintains thorough record for such claims. Administrators at the DEA were unaware that informants had filed for benefits with help from case officers. The Department of Labor, meanwhile, reported to auditors that its administrators do not enter informants’ claims into their electronic case management system due to DEA concerns over source security.

“[N]either the DEA nor DOL has accepted responsibility for judging the eligibility of [federal employee disability] cases originating from confidential sources,” the report summarizes.

In response to the report the Justice Department ordered a broad review of the DEA’s management practices.

Most immediately, the DEA placed a moratorium on new disability claims for confidential sources. Officials stated that informants are “presumptively not employees” for the purpose of benefit eligibility, save under “extraordinary circumstances.” Read the full report:

Image via DEA.gov