In August 1978, Admiral Stansfield Turner, who at that point had been the director of the Central Intelligence Agency for little over a year, held a town hall meeting in Anaheim, California to discuss the future of the CIA.

Turner had arrived at the Disneyland Hotel (a surprisingly popular destination for spooks) at the end of a whirlwind tour of the Golden State, having just been photographed at a Kiwanis Club luncheon in San Diego a few days prior. The tour was in part an opportunity for Turner to make the case to the public that the former Navy man was running at tight ship at the Agency, striking a (somewhat) conciliatory tone after the Church and Pike Committees just three years prior had left the CIA (somewhat) humbled.

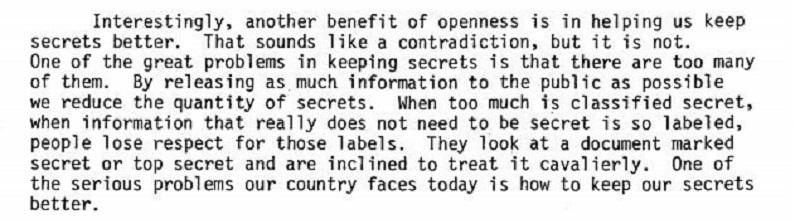

With a newly strengthened Freedom of Information Act and other reforms appearing to usher in an era of unimaginable - and uncomfortable - openness on the Agency, Turner seemed to be trying to embrace it. Turner suggested that one of the ways to preserve the CIA’s secrecy is to be less selective in what is considered a secret. Classification, like crying wolf, is something best reserved for the situations that truly call for them, lest the designations lose their importance.

That embrace of transparency came with a strong caveat, however.

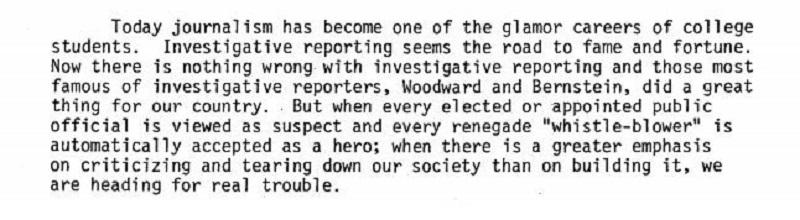

Invoking the watershed moment in American consciousness that was Watergate, Turner surprisingly downplayed the revelations of the subsequent years and Congressional investigations, decrying journalism and oversight as the tools of glory-seeking bomb-throwers were out to build a reputation by tearing down things that matter.

Simply put, they were irritating, regardless of how much shell-fish poison the Agency may or may not have stockpiled.

While Turner’s concerns over the dangers of overclassification do appear to be genuine, it was a warning that was all too quickly forgotten. Rather than pragmatic adoption of reform in the face of scandal it was doubtlessly intended, Turner’s pushback against encroaching transparency could instead be seen as one of the earliest steps of the CIA’s hard pivot back to opacity that began with the outcry over the exposure of undercover officers in the pages of Covert Action Information Bulletin and reached its crescendo under the Reagan Administration.

Even the transcript of that town hall meeting wasn’t declassified until 2007, 30 years shy of Turner’s speech. Even then, it’d be another ten years before the Agency made its declassified archive CREST available online as a result of MuckRock’s lawsuit and Emma Best’s advocacy. Prior to that, one had to make a trip to the National Archives annex in College Park, Maryland, and use one of four available terminals, all of which were under video surveillance to ensure that no “bad guys” were accessing the all too theoretically “public” information.

That’s also assuming you even know what you’re looking for. I only uncovered this anecdote because I happened to be in Anaheim for a conference my wife was attending, and I was bored.

I’m a firm believer in the editor’s mantra that if you do something yourself, it’s because you’ve failed to find someone who can do it better. I’ve been extremely fortunate to work with ludicrously talented and knowledgeable writers over the past five years that can do a far better job than I can of capturing the moral terror of what has been done and what is continuing to be done by an Agency which is ostensibly operating in “our” best interests. As I saw it, my role was to support them by writing sillier pieces that were more likely to get shared around the water cooler.

The hope was that by luring in audiences with appetizers, they might stick around for veggies, and learn something in the process. But even with that admittedly rather naive approach, I still found myself facing tough decisions.

For example, when I was putting together my story on an amusing incident in which an Agency employee tried to smuggle chicken out of the cafeteria in her purse, I cross-referenced a date on one of the files and realized it coincided with the Indonesian mass killings, with which the CIA was an active participant. I did not mention that historical fact in my light-hearted tale of Agency cafeteria capers.

I instead referenced the CIA’s attempts to murder Fidel Castro, as apparently attempted assassinations are okay so long as they are unsucessful and seem to draw their inspiration from Tex Avery.

Transparency is both cumulative and deeply uneven. I may go in intending to write about ham sandwiches, and by so doing, build off the existing work that requires me to make a call about whether or not I want to include a reference to genocide. As I always tell people about to take a plunge into the Agency archives: the odds are against you finding what you’re looking for, but they’re even that you’ll find something. And usually something pretty damn interesting.

I closely monitor the #FOIA hashtag on Twitter, and I’m always amused by the constant claims that a recently filed request by so-and-so is going to result in earth-shattering revelations that will finally take down the Deep State. It’s not that such revelations are impossible, or even impossible to obtain through FOIA, it’s that even in a best case scenario the process will still take years. One of my very first requests was for materials related to the National Security Agency’s youth outreach program “The CryptoKids.” I filed that request in July of 2014, assuming that something as benign as “Who decided that the anthropomorphic squirrel should play saxophone” would have a relatively quick turnaround, especially considering that the NSA was being inundated with questions about the activities of a tad more serious nature at the time.

That was over five years ago, and after successfully appealing a batch of responsive records I received in 2017 on grounds that they weren’t actually responsive to my original request, I’m again facing a completely uncertain timeframe as to when I might get a few emails brainstorming names for a cool dog that does cryptanalysis. That early frustration in the FOIA process taught me an important lesson about unearthing hidden history: There are no benign requests.

Agencies like the CIA justify rampant overclassification by citing the spectre of “Mosaic Theory,” the idea that even by releasing small bits of information you’re putting the whole system at risk. Those small bits can be rearranged to form a more comprehensive picture, like, indeed, a mosaic. It’s one of those things that sounds sensible enough, until you start following it to its logical conclusion.

If the Agency’s ability to operate effectively is legitimately threatened by the disclosure of a long-defunct Soviet Bloc beer brand, then it probably needs to address why its effectiveness was so tenuous in the first place. The argument is absurd on its face, which is why when we do actually manage to push back against the CIA’s broad discretionary power to decide what it will reveal about itself, it’s in those cases where disclosure is easier and less embarrassing than a long legal fight. And even then, those long legal fights happen. The lawsuit over the Agency’s declassified database was over its declassified database. It was already public, and the CIA still fought - and lost - over making it more so.

So while little victories are possible, they are, by definition, little. A friend and I spent over a year trying to solve the mystery of why the Agency had classified a photo of a birdhouse, and after cross-referencing material newly released through FOIA with more redacted versions of those same documents on CREST, we were able to determine that at some point in the ‘70s there was a birdhouse somewhere on the grounds of the CIA’s headquarters in Langley, and somebody took a photo of it. Instant state secret, and mystery solved.

Okay, so - 1. I found a photo of a birdhouse in the #CIA archives: https://t.co/c36Ii0vuv5

— JPat Brown (@resentfultweet) July 5, 2019

2. @NatSecGeek files a #FOIA regarding it: https://t.co/0SIn6K1hJ3

3. After a year of processing (which is unusually quick), CIA releases a slightly less redacted file that reveals ... https://t.co/8VxelOAItM

If you’ll permit me in saying so, it took a rather impressive amount of knowledge and familiarity with the subject matter even to make even this admittedly underwhelming discovery. The fact that the Agency at one point had a birdhouse is probably not going to change your opinion on it very much one way or the other. If anything, I concede that if you were inclined to not think too much about the CIA the fact that they would do something so earnest dad doofy as designate a birdhouse “building 12½” is mildly endearing, Indonesian mass-killings aside.

However, the fact that the birdhouse was a secret until remarkably recently is important, especially when placed in the context of the Agency’s argument that it’s self-anointed immunity to exposure is of critical importance. To echo Turner, the problem with over-classification is that it saps secrecy of it seriousness. When the CIA makes the claim that it can’t turn over records on extrajudicial killings or funding terrorist organizations or torture on grounds that that information is critical national security importance, they are doing so having made the same claim about a photo of a birdhouse.

When I wrote about the banality of the national security establishment - long lines at Starbucks, undercover bowling leagues, spies getting bored and taking cat photos - my intention was to highlight the discrepancy between these stories and the Agency’s highly cultivated public image as either unknowable, all-powerful, or both. Yes, it is one of the most terrifyingly destructive organizations of the last 100 years, but it’s also a place where people have hissy fits because grapes got left out of the jazz salad.

There are organizations such as the National Security Archive, which I linked to earlier, which are doing the Lord’s work in reclaiming the stolen history of 20th century.

I tried to help them and others in the cause by doing the one thing that I’m good at doing, which is making people look silly. And I did it because I believe we have a moral duty to hold our institutions accountable, even if our instruments of oversight have grown so impotent that we’re left with little more than ridicule.

Making light of absurd overclassification is not only cathartic, it makes us safer in the long run, as Turner himself argued. By limiting secrecy to the things that actual deserve it (which would involve a very public discussion about what meets that criteria), the CIA would not only reinforce the vital necessity of discretion, but it would also deprive glory-seeking bomb-throwers such as myself of ammunition for pot-shots.

It’s a win-win scenario, but one that would involve admitting that in some infinitesimal way the Agency is indeed bound by limitations, such as civilian oversight. As long as overclassification continues, so will articles about something stupid that was classified, even if I’m not writing them.

Bring it on. In the words of the man who signed the National Security Act of 1947 into law, and by so doing, created the CIA, “When history is written they will be the sons of bitches–not I.”

Image via Jared Rodriguez of Truthout and licensed under Creative Commons.