Mary Lou Oslund recovered quickly from COVID-19 for a 93-year-old, her daughter Pam Hentges remembers. So when Oslund died three months later, her daughter was surprised to see the words “COVID-19” listed on her mother’s death certificate.

Oslund, who lived in a Minnesota nursing home just across the border from her daughter in Wisconsin, spoke on the phone to her daughter almost every day. The first week that Oslund had COVID in late November 2020, the two didn’t talk much as usual. Oslund’s cough and congestion made it difficult to carry a conversation.

By the second week though, Oslund was feeling better and even joked that she must have just had a cold, Hentges recalls. The daily mother-daughter calls returned to normal. Oslund was mostly herself, just a bit weaker and more tired. But gradually her health and energy declined, and in January, Oslund died in hospice. Hentges was there with Oslund in the days leading up to her death; Oslund wasn’t coughing or having trouble breathing, she said.

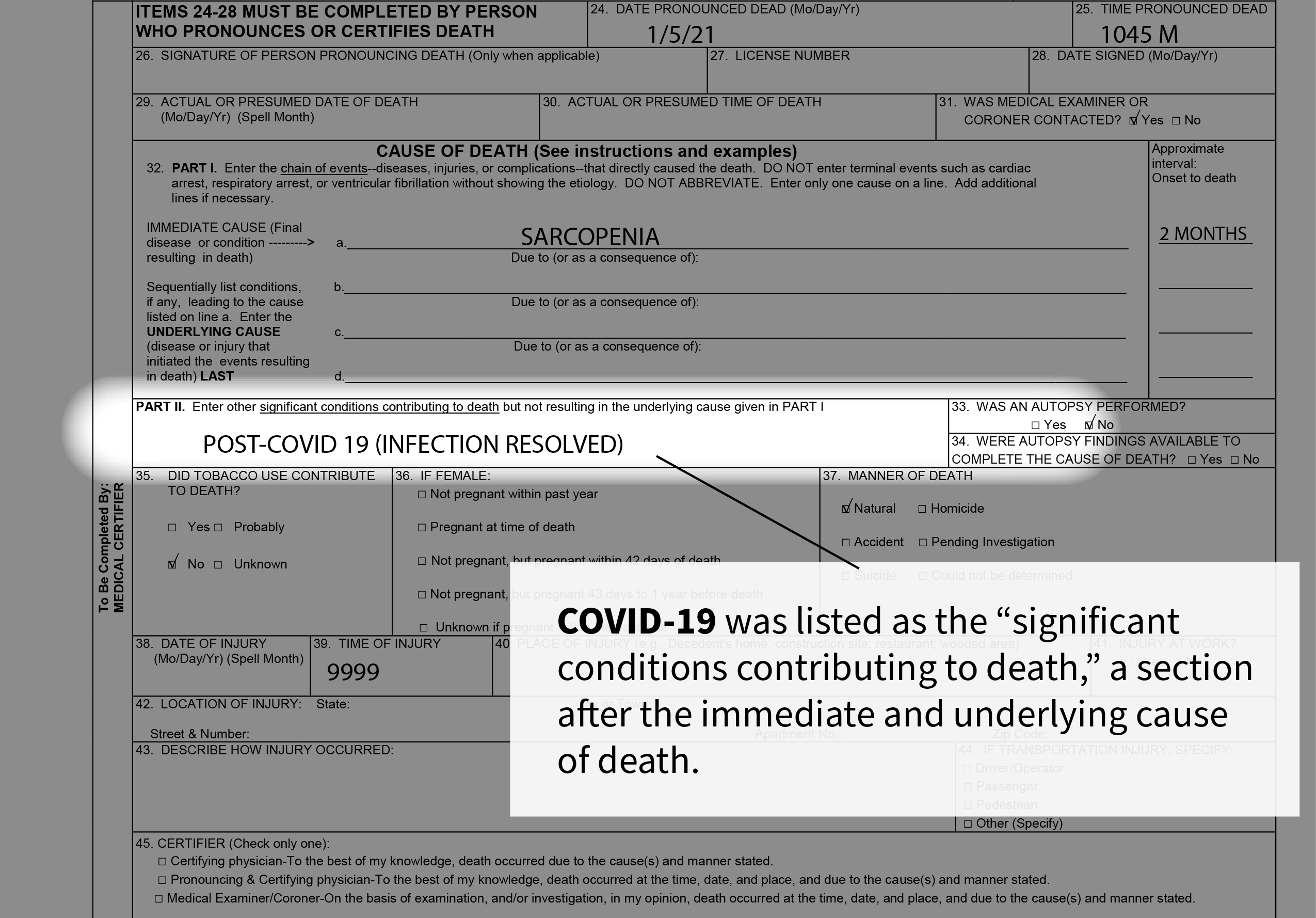

Still, COVID-19 was listed near the bottom of Oslund’s death certificate under “other contributing factors.” There, Oslund’s doctor had written that “Post-COVID-19 (infection resolved)” had been a factor leading to Oslund’s death.

The open question of whether Oslund and thousands of other Americans ultimately died of Long COVID reflects a lack of medical education about how to recognize this condition, especially when patients have initially-mild cases, experts say. On Wednesday, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released a study of thousands of so-called Long COVID deaths, where patients who had recovered from the virus ultimately died after experiencing lingering symptoms from the disease. More than a year after the CDC issued guidance on a new medical code for Long COVID cases, the agency has yet to clearly define how the chronic condition can contribute to death.

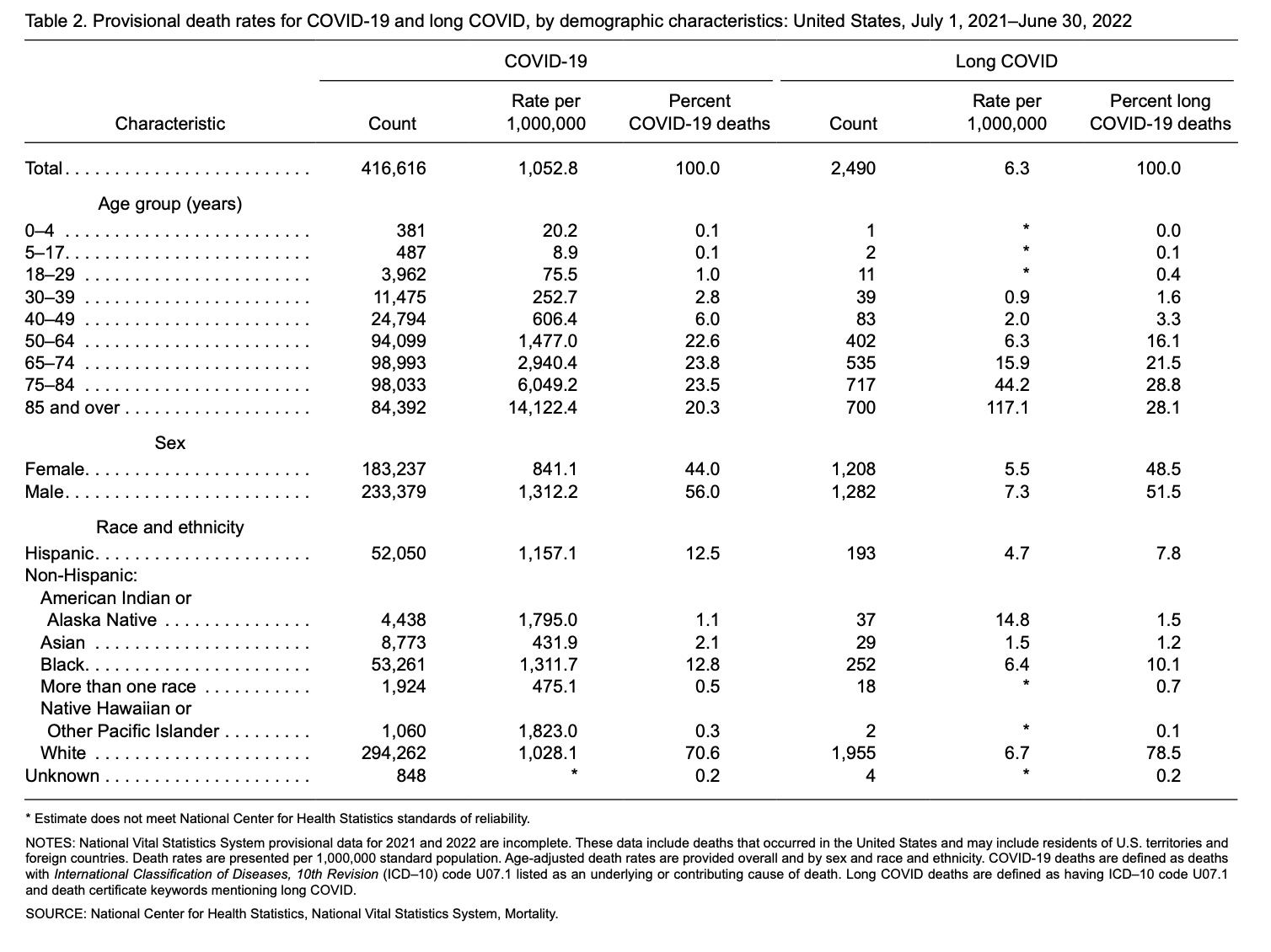

In reviewing death certificates, the CDC study found that Long COVID played a role in at least 3,544 deaths between January 2020 and the end of June 2022. While these deaths represent less than 1% of the more than 1 million Americans who have died from COVID-19, the review found that certificates naming Long COVID as a contributing factor increased this year — suggesting increased recognition of the dangers posed by long-term symptoms in 2022.

Still, experts who reviewed the CDC’s study said it almost assuredly represented a vast undercount of Long COVID deaths nationwide. And the small number of discovered Long COVID deaths speaks to systematic issues with health data systems in the U.S., which assumes everyone quickly recovers from contagious diseases with no long-term impacts, said Ziyad Al-Aly, a physician and chief of research and development at the Veterans Affairs St. Louis Health Care System, who has extensively studied Long COVID through VA medical records.

The CDC report is “a victim of the archaic data systems that don’t allow you to accurately capture the toll of disease and death in this epidemic of Long COVID,” Al-Aly said.

The technical term for Long COVID on death certificates and in other medical settings is “post-acute sequelae of COVID-19,” or PASC. The CDC is encouraging those who review and sign death certificates — physicians, nurse practitioners, medical examiners and coroners — to watch for signs of the disease and add it to death certificates but has stopped short of instituting a new official code for Long COVID in its data and papers, saying that it needs more time.

While increased risk of death after a coronavirus infection has long been clear to researchers studying this condition, experts say, the new CDC research gives new weight to this finding and “can hopefully move us to increased recognition of this really major problem,” Al-Aly said.

Almost 15% of all U.S. adults have experienced Long COVID, according to estimates from the CDC and Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey. The condition may have pulled 2 to 4 million Americans out of the workforce, the Brookings Institute reports.

People with the condition, also called “long-haulers,” experience a wide array of symptoms ranging from prolonged loss of smell to intense, debilitating brain fog and fatigue. Long COVID can worsen existing chronic conditions or increase risk of heart and vascular diseases, said Carlos Cordon-Cardo, chair of pathology at the Icahn School of Mount Sinai. Researchers like Cordon-Cardo, who is an investigator with the National Institutes of Health’s RECOVER initiative to study Long COVID, hope that examining how the condition contributes to death will shed light on its underlying biology – potentially leading to treatments.

The Documenting COVID -19 project at Columbia University’s Brown Institute for Media Innovation and MuckRock obtained detailed death certificate records from the states of Minnesota and New Mexico, allowing journalists to search for words associated with Long COVID. We also reviewed a more limited number of COVID-19-related deaths in California’s Bay Area, Los Angeles and San Diego, and Chicago’s Cook County.

We relied on words and phrases identified by the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics to find cases where Long COVID caused or contributed to the death, including terms like “post COVID syndrome,” “post acute” COVID and “Long COVID.” In 2020, 2021, and parts of 2022, we found 62 deaths associated with Long COVID in Minnesota, nine in Santa Clara County and one in Los Angeles. In New Mexico, from 2020 through 2021, we identified 13 deaths.

We attempted to contact the listed next of kin in many of the deaths in Minnesota, and in speaking with three families, were able to find more details on how and why deaths were certified as either Long COVID or post-COVID.

In both MuckRock’s research and the CDC’s study, the deaths identified through this process likely represent a vast undercount of the true number of people who have died with Long COVID, experts say. Through ongoing research and education efforts, future deaths like these may be quickly identified and studied to better understand the long-term effects of the coronavirus.

“We need continued medical education to improve recognition of Long COVID in patients and to use Long COVID-associated documentation,” said Hannah Davis, co-founder of the Patient-Led Research Collaborative.

Dozens of Long COVID deaths across the country

Of the 62 deaths associated with Long COVID in Minnesota, more than half occurred in 2022, a sharp increase in Long COVID deaths since the beginning of the pandemic that is also highlighted in the CDC study.

Long COVID was the underlying, or chief cause of death, in about a third of all deaths. Symptoms from the virus had lingered for weeks to months in these patients. They also had other significant comorbidities, including pneumonia, diabetes, congestive heart failure, Alzheimer disease, hypertension, dementia, chronic kidney disease, among others.

In several cases, Long COVID was listed with other, more vague contributing causes like “natural causes” or “failure to thrive.”

Most of the deaths were among patients over 75, though a handful were in their 30s and 40s.

The CDC’s study of death certificates found a similar pattern: adults ages 75 and older represented more than half of the Long COVID deaths identified, while the vast majority of deaths occurred in adults over age 50.

Older adults are at a higher risk of death from long-term COVID-19 complications just as they are from the acute disease, Al-Aly said. A patient in their 20s would have more capacity to adjust to a debilitating symptom, such as fatigue, than a patient in their 80s: for older adults, such symptoms “really put them in bed, and they decompensate from there.”

However, upon reviewing the CDC study, Al-Aly noted that the researchers’ reliance on death certificates may have caused deaths among younger adults to be missed. Older adults who have more severe COVID-19 early on tend to be better represented in medical records of long-term symptoms, he said, compared to younger adults who might have complications like heart attacks that are less directly tied to initial respiratory illness.

Many of the Minnesotans who had Long COVID listed on their death certificates lacked a college degree and worked in blue-collar jobs, including as a farmer, carpenter and bus driver. Reflecting Minnesota’s demographics, almost all cases were white.

The health professionals who certified the Minnesota cases used a mix of different phrases to describe Long COVID, reflecting the ambiguity over how to define the relatively new disease. Phrases included “Post-COVID Inflammatory Syndrome” and “Hypoxic Respiratory Failure Post-COVID-19.”

In California’s Los Angeles County and Chicago’s Cook County, the terms of “post-COVID” and “Long COVID” were virtually nonexistent on death certificates logged with each county’s medical examiner. Medical examiners oversee a large proportion of deaths that occurred at private homes and nursing homes but a smaller percentage of those that occurred in medical facilities.

In New Mexico, the medical examiner’s office oversees all death investigations across the state. Unlike the deaths in Minnesota associated with Long COVID, many of the deaths among New Mexcians did not indicate that the patient had significant comorbidities, but instead connected the death directly to pneumonia or respiratory failure related to COVID-19.

The youngest patient was a 25-year-old Indigenous man, a dental assistant who lived near Navajo Nation and died in November 2020.

Long COVID was documented as the underlying cause of death in five of 13 New Mexican patients, all of whom died in 2021. The age of these patients spanned from 68 to 89, and most were frontline or essential workers with occupations like farm hand, security guard or housekeeper.

About one-third of patients were under 60 years old and three-fourths were Hispanic or Indigenous Americans, reflecting both the demographics of New Mexico and the toll of COVID-19 on communities of color.

Among the Long COVID deaths identified in the CDC study, the vast majority occurred in white people, though Indigenous Americans had the highest death rate when adjusting for population.

The report’s authors noted that higher COVID-19 death rates in the disease’s acute phase among Black and Hispanic Americans could result “in fewer COVID-19 survivors left to experience Long COVID” in these groups. Limitations in access to health care — particularly access to the advanced care often needed for a Long COVID diagnosis — could also contribute to the lower Long COVID death rates identified in the study.

White people are more likely to see doctors educated in Long COVID compared to other race and ethnicity groups, said David Putrino, an expert in rehabilitation medicine at Mount Sinai whose lab was one of the first to begin researching Long COVID in 2020. This trend in access can bias datasets like the CDC’s towards white people, he said, while doctors’ tendency to diagnose Long COVID in patients who had severe symptoms early on can bias the data towards older adults.

“What we have here is a health disparity on top of a health disparity,” Putrino said, “which leads to the data being skewed.”

A new direction in understanding the impact of Long COVID

Despite the millions of Americans impacted by Long COVID over the last two years, the condition is poorly tracked, with no set medical definition or existing treatments. Most public health data systems stop tracking patients after 30 days, Al-Aly said, which often makes it difficult to clearly link long-term symptoms to an earlier coronavirus infection.

By learning how Long COVID patients die, researchers may be able to better understand how the coronavirus produces lasting organ damage. This is the hypothesis of a study aiming to perform autopsies on hundreds of patients, said Andrea Troxel, a biostatistician at NYU Langone Health and lead investigator for the trial.

“This is the largest-scale autopsy study that anybody I’ve spoken to has ever seen,” Troxel said. The study includes nine academic hospitals and research institutions across the country, which are aiming to collect samples from 700 deceased patients over the course of four years. It’s part of RECOVER, a billion-dollar initiative from the National Institutes of Health to study Long COVID.

Like other facets of RECOVER, the autopsy study has moved slowly and faced challenges. As of mid-December, the trial has enrolled more than 85 patients. For each deceased patient, researchers have conducted a detailed physical exam and collected samples from 51 different sites in the body. “It’s much more comprehensive than your generic, standard autopsy,” Troxel said.

The samples are currently stored in a tissue bank at the Mayo Clinic, Troxel said. Once participating sites have collected more samples, they will be analyzed for potential markers of Long COVID, such as continued presence of the virus long after a patient was infected — an indicator found in other studies.

This continued presence indicates that “some pieces of the viruses are still circulating” throughout the body, said Cordon-Cardo, who leads the autopsy study at Mount Sinai. Persistent virus circulation is known to be a cause of chronic inflammation in other post-viral diseases, Cordon-Cardo said. He suspects a similar process may contribute to Long COVID symptoms.

In an ideal world, people whose death certificates were identified in the CDC’s research would be perfect candidates for RECOVER’s autopsy study. But the CDC and RECOVER are not currently working together, and the quick timeframe needed to collect autopsy samples may make such a collaboration impossible.

“We have a limit of 24 hours between time of death and beginning the autopsy in order to preserve the quality of the tissue samples,” Troxel said. After that first day has passed, body tissues degrade and won’t be as useful for research. The CDC, on the other hand, can take months to process death certificates.

Due to the 24-hour time limit, most deceased patients enrolled in the autopsy study are recruited from hospitals, working in conjunction with intensive care and palliative care physicians. One study site, at the University of New Mexico’s Health Sciences Center, is the exception. This center serves as the medical examiner for the state of New Mexico, allowing researchers to quickly identify potential Long COVID deaths among those happening across the state, not just in hospitals.

The RECOVER research may contribute to the CDC’s work on a new category of death for Long COVID. Such a code would be “a welcome addition” to U.S. mortality data, said Al-Aly, the VA researcher. It could enable more research such as RECOVER’s, investigating how a coronavirus infection contributes to future risk of death.

But physicians, coroners, medical examiners and others filling out death certificates would require “a lot of education” to correctly identify and log the condition, he said. Troxel similarly noted that even death categories that seem straightforward are often used differently in different places.

The end-goal in this work for researchers, as well as Long COVID patients themselves, is developing treatments for this debilitating condition — and preventing more deaths in the future. Right now, clinicians are able to treat the symptoms of Long COVID, Cordon-Cardo said; “but we don’t know the real reason, the real causation” for those symptoms.

While older patients are more at risk of death from Long COVID in the short-term, the long-term impacts of this condition are not well understood. Patients also face an elevated risk of suicide, another condition that should be urgently tracked, said Putrino, the rehabilitation expert. While the CDC itself might be “ill-equipped” to study suicides linked to Long COVID, it could collaborate with patient advocacy groups that are already working on this issue, he said.

Putrino also wants to see federal agencies create national registries that can follow Long COVID patients over time, tracking mortality and other ways that the condition changes people’s lives. “Death has not been the problem for the majority of folks with Long COVID,” but rather “the complete lack of a functional life,” he said.

What next of kin in Minnesota know about their loved ones’ deaths

Hentges believes that the information on her mother’s death certificate is accurate, even though she didn’t fully realize the continued effects of COVID on her mother’s health at the time.

“When you have something that traumatic that’s affecting your body, it makes sense that a few months later, you’re not going to be 100% back to normal — if ever,” Hentges said.

Though Oslund largely recovered from COVID-19, Hentges says that a few things about her mother’s health did change permanently. Oslund had a lingering cough and seemed more tired. Their daily phone calls had to happen earlier, never much later than 7 in the evening.

While the effects of the virus on Oslund’s health continued across months, the next of kin for two other Minnesotans who died of complications described as “post COVID” reported that their loved ones died a month or less after having COVID.

Vladimir Ryzhevskiy, an 82-year-old former truck driver from Osseo, Minnesota, died about a month after first contracting COVID-19. His son, Edward Rijevski, said that his father had recovered from COVID after two weeks of being in the emergency room, but then declined quickly after being moved to the hospital’s rehab center. The main cause of death on Ryzhevskiy’s death certificate is “COVID-19 Pneumonia and Post-COVID Inflammatory Syndrome.”

“If it weren’t COVID-19, of course he’d still be alive,” Ryzhevskiy’s son Edward said.

Patricia Dahl, an 88-year-old resident of Minneapolis, died a month after first contracting the virus. One of the causes of death on Dahl’s death certificate is “Post COVID-19 Pulmonary Fibrosis Syndrome.”

Her daughter, Paula Bell, a 68-year-old who used to work as a data coordinator and medical secretary for long-term care facilities, was surprised that her mother bounced back from COVID despite her history of asthma and emphysema.

“For an 88-year-old woman to survive COVID, I thought was pretty amazing,” Bell said.

But after contracting the virus, Dahl developed pneumonia. When she died a month later, pneumonia was listed on her death certificate as one of the conditions, along with “Post COVID,” that ultimately led to her death.

Bell, who is familiar with diagnoses and procedures for death coding from her job as a medical secretary, said she understands that it’s complicated to discern what played the biggest role in someone’s death. It’s not just that her mother had COVID and then passed away, Bell says, because her mother had other illnesses before COVID too.

“Where do you draw that line?,” Bell said.

Experts studying Long COVID say that Bell’s question is tough to answer.

“As with any post-viral syndrome, it’s often really hard to prove that somebody dies of the syndrome as opposed to with the syndrome,” Putrino said.

Still, a number of studies from groups like Al-Aly’s have found that, after a COVID-19 case, patients have higher risks of heart disease, lung problems, brain damage and problems in other organ systems. Such damage can exacerbate chronic conditions that patients had prior to getting COVID-19, or can simply increase their chances of medical events such as heart attacks.

Consider a patient who suffers from blood clots after a coronavirus infection, then develops a pulmonary embolism resulting in their death, Al-Aly said. “Clearly, that person had Long COVID, developed clots in their lungs, and that led them to die.”

Some physicians might code such a patient’s death as “post-COVID” while others might not include COVID-19 on the death certificate. In some cases, the person signing a death certificate might not be aware that a patient had a prior COVID-19 diagnosis or long-term symptoms, especially if their infection occurred a long time before their death.

While clinical education catches up to the reality of Long COVID, Al-Aly suggested that analysis of premature death following a coronavirus infection could offer a more comprehensive picture of the condition’s risk. He would like to see the CDC perform similar studies to what his team has done with VA records, but on a larger scale.

At the same time, institutions like the CDC should do more to educate people about the long-term problems that could follow a COVID-19 case, said Davis, the patient researcher. “We need public warnings about risks of heart attack, stroke and other clotting conditions, especially in the first few months after COVID-19 infection,” she said, along with warnings about potential links to conditions like diabetes, Alzheimer’s and cancer.

For Hentges, the effect of the pandemic on her mother’s health also means more than just the effects of the virus. Oslund got her energy from being around other people. Before the pandemic, she often played cards in a group or visited friends who weren’t as mobile as her. The isolation of stricter safety measures at her nursing home took its toll on Oslund.

“I always said the pandemic was going to kill her one way or another,” Hentges said.