Paul Hines strode through the hallway of Quincy, Massachusett’s Broad Meadows Middle School, stopping in front of a water cooler placed between two cardboard sheets taped to the wall.

As the footsteps of middle school children echoed behind him, Hines peeled off the tape from one of the cardboard pieces to expose supply pipes that once led to a water bubbler. That bubbler was demolished after water from it was tested, revealing elevated levels of lead. Hines returned the cardboard cover back to the hole in the wall and walked towards the school kitchen, pausing his explanation of the drinking water’s lead testing to allow the sounds of the school band to fill the hallways.

Hines, 55, has lived in Quincy since 1965. He works as Commissioner of Public Buildings in Quincy and is a parent to twin sons who are freshmen at North Quincy High School.

Image via Quincy Public Schools

“My kids are active in school. They drink the water all day long, and they shouldn’t be ingesting high levels of lead,” he said.

As a parent, he was surprised by the large number of fixtures throughout the city’s public schools that registered elevated lead levels, and ever since taking over as Commissioner, he has led the charge to make the drinking water in Quincy’s public schools lead-free. But the issue is far from limited to this South Shore city - Broad Meadows is just one among hundreds of public schools across Massachusetts that have reported high levels of lead in their drinking water through statewide testing conducted in 2016 and 2017.

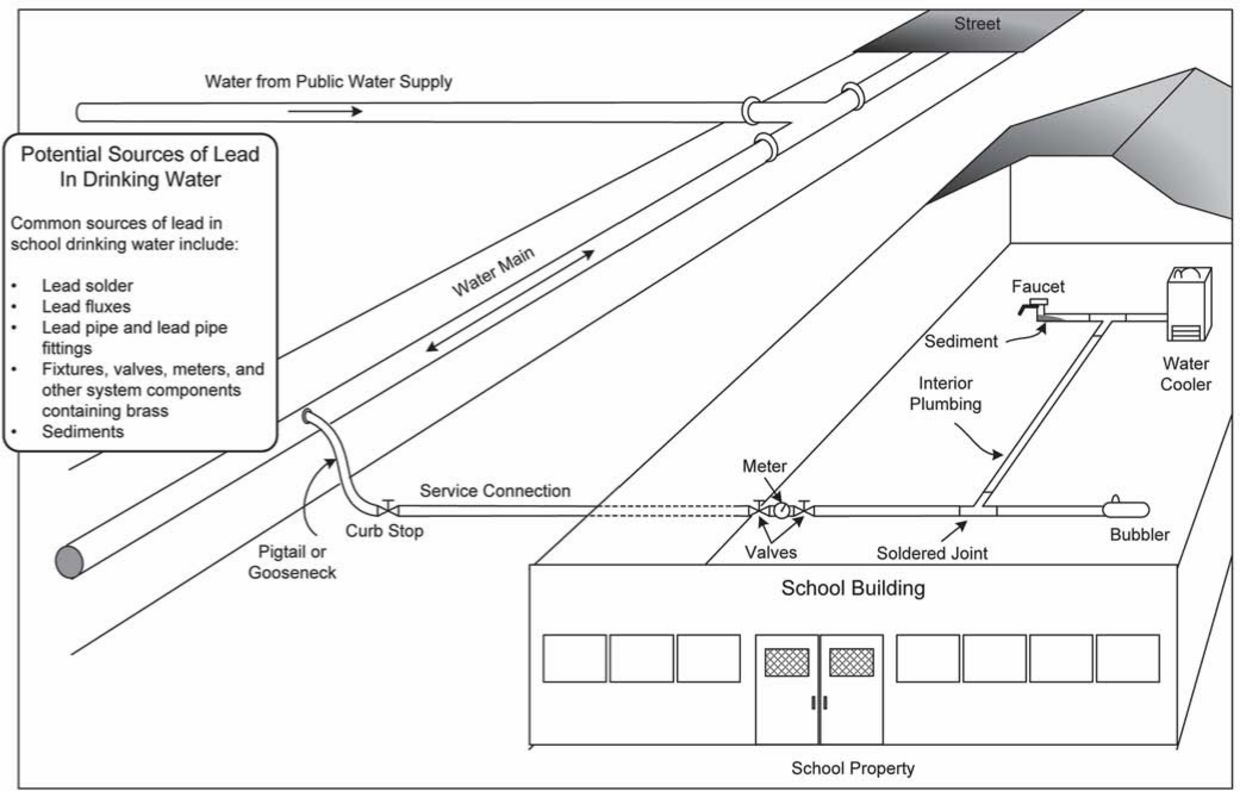

Lead gets absorbed into water through contact with pipes, fixtures or solder containing the metal. This process is called leaching, and it’s similar to how tea bags impart their flavor to warm water.

The public health hazard caused by elevated lead levels in drinking water drew national attention through Flint, Michigan’s water crisis, though the dangers of lead exposure have been known for decades and previous studies on the dangers of lead poisoning have made evident the importance of testing residential water sources.

In Massachusetts, a law limiting the levels of lead allowed in residential buildings has been on the books since the ’70s.

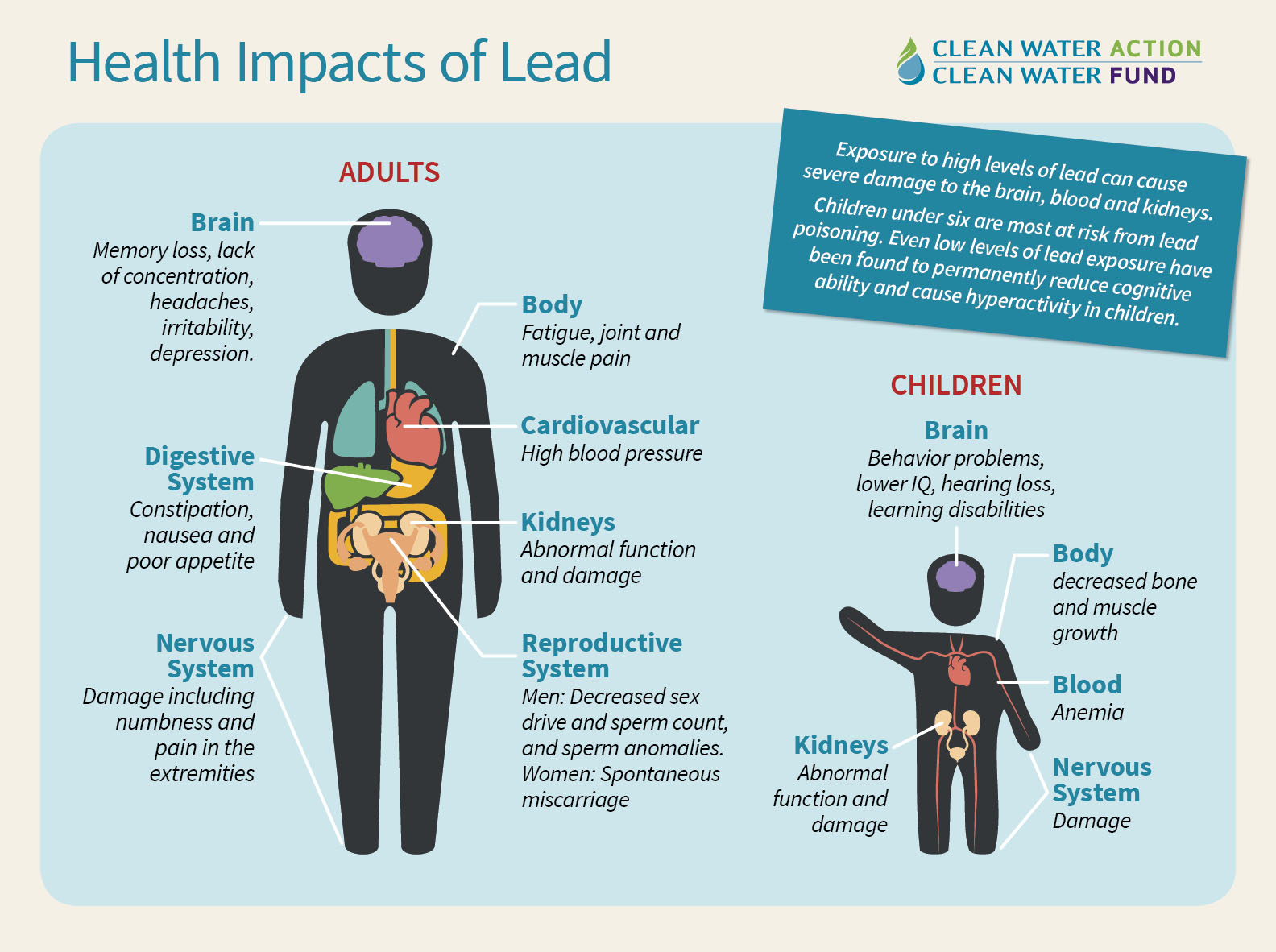

That rule was inspired by research that has revealed that infants and children are most severely affected by ingesting lead, and the Bay State has introduced other efforts to attempt to limit lead levels in the young.

However, lead testing in schools still isn’t treated with the same level of importance. Only six states in the country mandate lead testing in public schools, according to a News21 analysis, and Massachusetts is not one of them, although the state has established the Lead Contamination Control Act to educate and assist public schools with lead testing. Similarly, the Environmental Protection Agency’s federal Lead and Copper Rule fails to mandate that public schools test their water for lead levels.

Image via Mass.gov

“Only schools that are considered ‘public water suppliers’ are required under the Federal standards to test their drinking water for the presence of lead,” said Emily Bender, a public affairs specialist at the EPA, clarified in an email. “In general, most school districts in the US are served by public water utilities, so the school itself is not required to perform any drinking water testing.”

Though the EPA recommends lead testing, making it optional means that schools can get away with not checking their drinking water for lead, which is known to be most harmful to growing children.

According to studies, lead ingested in low levels has been shown to cause health risks that might not immediately land kids at the doctor’s office, like behavioral problems and learning disabilities. Higher levels of lead can cause severe damage, primarily to the central nervous system but also to bones and kidneys.

Image via CleanWaterAction.org

“Our children are in schools eight-plus hours a day,” said Dr. Patricia Janulewicz, an environmental health expert and professor at Boston University’s School of Public Health. “That is a lot of potential lead exposure.”

Janulewicz is also a parent who believes schools should be mandated to test their drinking water for lead and take immediate action upon finding high lead levels. “We all should know by now, not just within the public health field, that lead is dangerous,” she said.

Driven partly by the Flint crisis - where the EPA didn’t get involved until months after the crisis became evident - the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection, launched the Assistance Program in 2016 to help public schools all over the state to test their drinking water for lead. Through the program, DEP and the University of Massachusetts provides technical assistance to local schools all over the state.

“When a school system joins the program, we help set up a testing protocol for them,” explained public affairs director Ed Coletta. The setup includes identifying fixtures that need to be tested and conducting sampling.

“All the samples are sent to a state-certified laboratory. When the results come back, we try to work with the local community or the school officials to get the word out to the community and take steps that work for them to address the issue.”

“The long term plan is to make these communities self-sufficient so that they can do their own testing,” Coletta added.

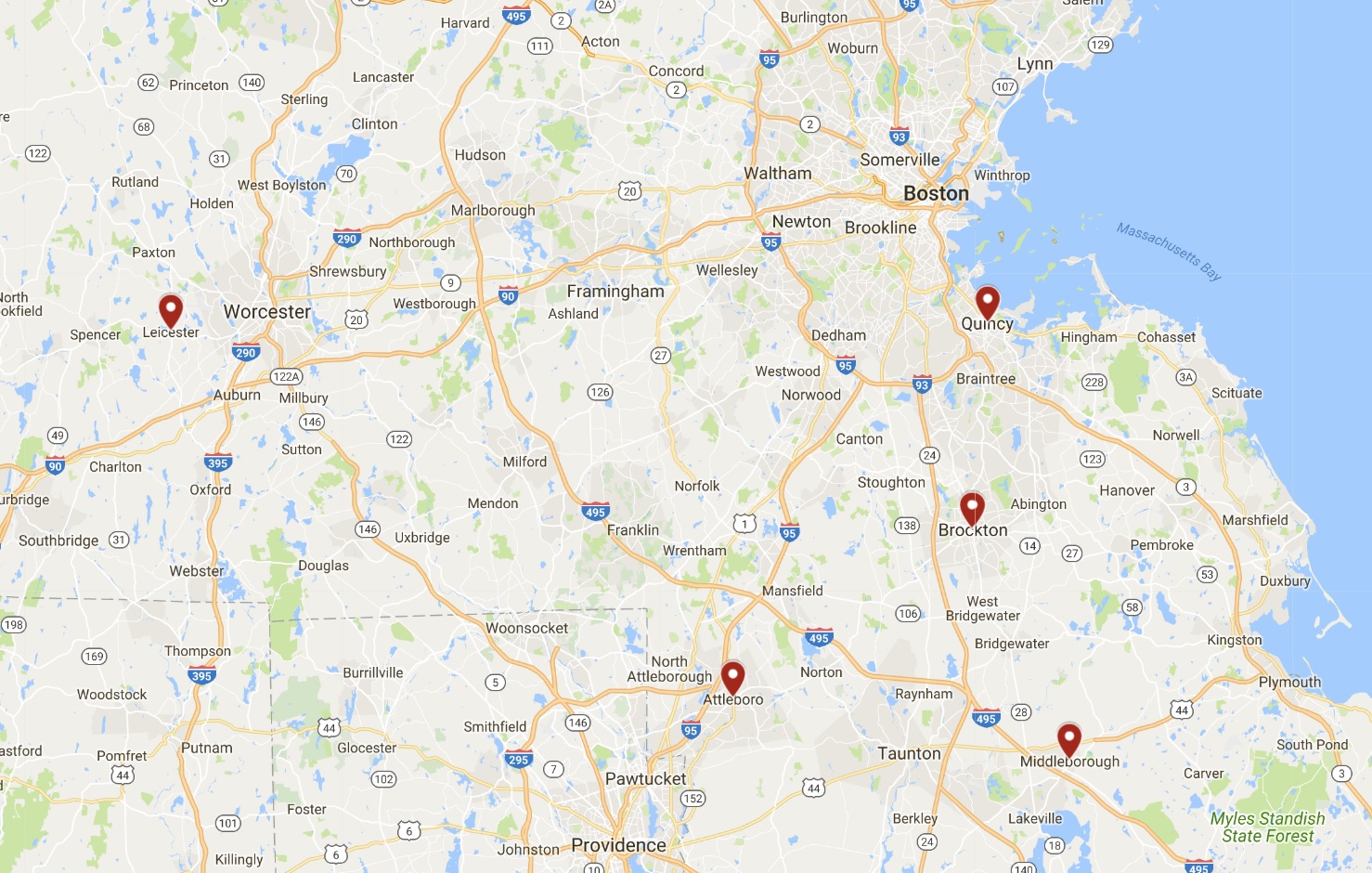

Through this assistance program, cities and towns all across the state reported results of the testing, which showed that hundreds of schools had elevated lead levels. The school districts of Attleboro, Brockton, Leicester, Middleborough, and Quincy, all found the highest levels of lead in their school buildings.

The amount of lead in the water depends on many factors: the capacity of water to react with lead and absorb it (called corrosiveness), the amount of time that water is in contact with the lead source, the water temperature, and so on. In most of the five school districts, the highest levels of lead were caused because the water remained stagnant for weeks or months inside a forgotten fixture or kettle, which was run after a long time just to take a testing sample.

The EPA has set an “action level” for lead in drinking water equal to 0.015 mg/L, or 15 parts per billion. Anything above this action level is considered unsafe for consumption. This action level is a regulatory measure more than a scientific one, since even a blood lead level lower than 10 ppb can be linked to health risks.

The highest individual result found in North Quincy High school was 42,000 ppb, which is more than eight times of 5000 ppb lead, above which water is classified as “hazardous waste.” Each of the five cities and towns had fixtures that tested higher than the hazardous waste limit, according to the database of test results.

Regardless of the causes, it was clear that five communities in Massachusetts faced the same problem: their school water was unsafe for kids.

We’ll take a closer look at each of them next week in Part Two, in the meantime, you can explore the completed requests below.

Image by Paul Goyette via Flickr and is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0