As we wrote last week, the school districts of Attleboro, Brockton, Leicester, Middleborough, and Quincy, all found the highest levels of lead in their school buildings. Today, we’ll be taking a closer look at all of them.

Attleboro

Image via Attleboro Public Schools

The city of Attleboro is roughly 39 miles from Boston and just 10 miles from Providence, Rhode Island, yet it seems to exist in a world of its own. Intent on preserving its history, the city has four museums and a park named after the jewelry company that earned Attleboro its old nickname: the jewelry capital of the world. A few blocks of Historic Downtown, marked with blue signs, seem like the only busy part of the city. The rest is quiet streets and residential neighborhoods.

Attleboro’s sprawling high school building is located roughly a mile away from downtown. Because of its size, the building is unusually quiet during school hours. Facilities Manager Jason Parenteau’s footsteps echoed as he walked to through the halls adorned with students’ paintings. He ducked into a room and pointed to a water filtration station in the far corner. These stations were put in place after Attleboro found lead in the water at the old high school building.

Two years ago, Attleboro tested the water in its schools to find vastly different lead levels, ranging from zero in newer buildings to a shocking 38,400 ppb in Wamsutta Middle School. However, the school district experienced a unique problem with DEP’s initial tests through the assistance program.

“We found that the lab results were unreliable,” said Director of Finance for public schools, Marc Furtado. “So we reran tests and they tested fine, or we replaced fixtures.” Furtado added that the lab that DEP sent the samples to was responsible for the wrong results.

The town’s independent retests were verified by the DEP, but a few fixtures still tested high after the final sampling, including some of the highest levels that were initially recorded.

“We took those offline and we’re in the process of changing out the fixtures and retesting,” Parenteau explained, describing work currently underway at Wamsutta and Cyril K Brennan middle school. “If we find that our lead levels are still high, it’s not as simple as changing the fixtures.”

The money for all the remedial actions the school district took came from the public school’s facilities budget, a cost which Parenteau and Furtado said was not evident when they volunteered for the assistance program.

“We thought it would be zero when we started it, turned out to be 25 to 50 thousand total, between the filtration stations, the fixtures and the testing,” Furtado said.

In 2022, three of Attleboro’s old buildings that are partly used for school classes or learning programs will be relocated to the newly-built high school. During the interim, fixtures in the high school have been shut down, but not replaced. The filtration stations that Parenteau pointed out were placed in the old high school building to act as a temporary water source.

Attleboro’s communication policy prioritized giving the parents reassuring information over timely details of the testing. The school district chose not to send the initial test results home with the kids, worrying that it might cause trouble with the parents, like it had in the neighboring town of Norton.

“We waited until testing showed that the building was clean, then sent a letter [to parents] saying on this date we tested, here are the findings, here’s the retest, everything’s fine.” Furtado said.

Brockton

Image via Brockton Public Schools

Just south of Quincy is the industrial city of Brockton, decorated with an abundance of wire fences and warehouses . Brockton proudly showcases its sports, as evidenced by the 20-foot tall bronze statue of boxer Rocky Marciano located in Champion park, on the Brockton High School grounds. This enthusiasm carries over to the public schools’ sports success.

On a warm Sunday afternoon, kids of all ages were running around the high school football field while parents sat on foldable lawn chairs and watched their kids play through the fence.

Brockton’s school district has an enrollment of roughly 15,000 students, making it the largest of the five communities to face problems with lead in drinking water. Additionally, Massachusetts Department of Public Health has classified Brockton as a high risk community for childhood lead poisoning.

According to state law, all children are tested for blood lead levels between 9 and 12 months and again at ages 2 and 3. For high risk communities, DPH recommends additional testing when children turn 4. Determination of high risk communities is not based on lead water content in public schools, but it is increasingly important for these school districts to test and resolve any threats to kids’ health.

In 2016, the DEP’s tests revealed more than 300 fixtures with elevated lead levels throughout 23 public schools. Brockton High School alone reported more than 100 high levels, the highest one being 33,500 ppb. According to Deputy Superintendent Michael Thomas, the extremely high samples were from faucets that hadn’t been used in years.

“They were sinks that were filled with books and storage items, but we tested them all. So it was a result of water just sitting there in that fixture for probably 8 to 10 years,” he said. Brockton was quick to act when they discovered elevated results. “As soon as the readings came back and were sent to us from the Department of Public Health, the source - the faucets, the water fountains - were shut off the same day.”

When funding becomes available, all the faulty fixtures will be replaced with filtered hydration stations. Thomas has already allocated some of the school budget towards the stations, which filter the lead and copper out. Replacing each fixture with a hydration station costs about $2000, according to Thomas. He said that over $100,000 has been spent on replacing fixtures with hydration stations over the past 4 or 5 years.

Brockton’s approach to the lead problem was remarkable because of the school administration’s transparency. For all Brockton school buildings, results of the 2400 samples taken were posted on the public schools’ website, along with information from Massachusetts Department of Public Health that answers some basic questions about lead in drinking water.

“We sent out letters to parents of students and we also informed all the faculty,” Thomas added.

Brockton is continuing efforts to replace bubblers with pre-filtered hydration station while maintaining transparency and communication efforts.

Leicester

Image via Leicester Public Schools

With a population of just over 10,000, Leicester is the smallest town among the five school districts with the highest lead levels. It’s separated not only by distance from the other four communities that reported high lead results, but also by the approach of the town to the lead in school water issue.

Three out of Leicester’s four public schools are grouped together in the northeast quarter of the town, within a mile of each other. Leicester Middle School, Leicester Primary School, and Leicester High School are connected by unnamed paths, forming a sprawling campus bordered by trees on two sides. Leicester Memorial School is a few miles southwest of the other schools. All four schools were found to have some fixtures that tested high for lead, according to a letter sent in November 2016 by former Superintendent Judy Paolucci.

“The administration takes these results very seriously, and is moving immediately to safeguard the health of the students, faculty and staff,” Paolucci wrote. “Although most of the taps that exceeded the action levels for lead and copper are not used for drinking water, we have shut down all such taps to ensure that students and staff are not exposed to these metals.”

According to Paolucci’s letter and the MassDEP test results, Leicester’s public school drinking water clearly had a lead problem. However, Paolucci has since left her post in the school administration and so has the facilities director who, according to the current staff, had extensive knowledge of the lead tests.

The current school administration does not want to share any details about testing or remediation efforts. School committee chairman Scott Francis wrote in an email, “We have no issues to report with our water at Leicester Public Schools.”

Superintendent Marilyn Tencza acknowledged the initial testing but did not provide any further information. “I know there has been testing, but I don’t know the details,” she said.

Simply judging by Paolucci’s letter, there are discrepancies in the results reported in the MassDEP database, and the results Leicester sent out to parents. The letter states only 21 fixtures that tested above the action level of 0.015 mg/l, but the MassDEP database showed 31.

The MassDEP data for Leicester indicated that all remedial actions including posting on the faucet to prevent drinking, notice provided to consumers, replaced plumbing or fixture, daily flushing and retesting were taken by the school district. Some of these, however, are contradictory to others, like replacing a fixture should eliminate the need for daily flushing. Since the school administration has provided no proof of retesting or results of retests, and besides the superintendent’s letter, there is no confirmation that the plan of action included in her letter was actually carried out.

Middleborough

Image via Middleborough Public Schools

The town of Middleborough with its idyllic houses with yards and picket fences, seems to be striving towards the ideal suburban lifestyle. On a weekday afternoon, locals chatted with each other in a coffee shop on the town’s bustling Center Street that the barista called “the Central Perk of Middleborough.” Meanwhile, less than a mile away, working parents rushed in and out of the two public elementary schools that share the same campus.

Both elementary schools did not report any lead problems in their drinking water, but Middleborough High School’s testing revealed elevated levels, including a kitchen kettle which had 28,100 ppb of lead.

Facilities Director James Hutchinson walked through the cluttered facilities room at the Henry B. Burkland Elementary School to his desk, explaining the actions that Middleborough had taken after high lead results were found.

The problematic fixtures and kettles were shut down, he said, running his pen through the printed list of fixtures in each school. “Handwashing only” signs were posted next to sinks that tested high. As there were no lead pipes in any of the public schools, Hutchinson and his team knew the lead was localized to fixtures or solder.

“We were very transparent from the get-go on this,” Hutchinson said, in regards to communicating with the parents through the superintendent. “The plan was to let parents know that testing had been done in all schools, and that they had access to the DEP website if they chose to look at the results.”

Hutchison was joined in the mitigation efforts by the school facilities staff and engineer Richard Johnson.

Johnson, a longtime Middleborough resident is a parent to two kids who used to attend the town’s public schools. He spent months working with Hutchinson, the facilities staff and the DEP to test every classroom sink, kitchen kettle and water bubbler, and retest the ones that indicated elevated levels. He was also involved in the mitigation efforts after retesting.

“Overall the town did very well, and gave the water department and the school department some assurance that the children were getting good quality water.”

Johnson, who works in the private sector as an engineer, volunteered months of his time to the town’s lead testing and remediation efforts.

“The driving force was an opportunity for me to give back to the community, and I had three kids that went through the school system, and the school system did a very good job educating them, so it was a fair trade,” he said.

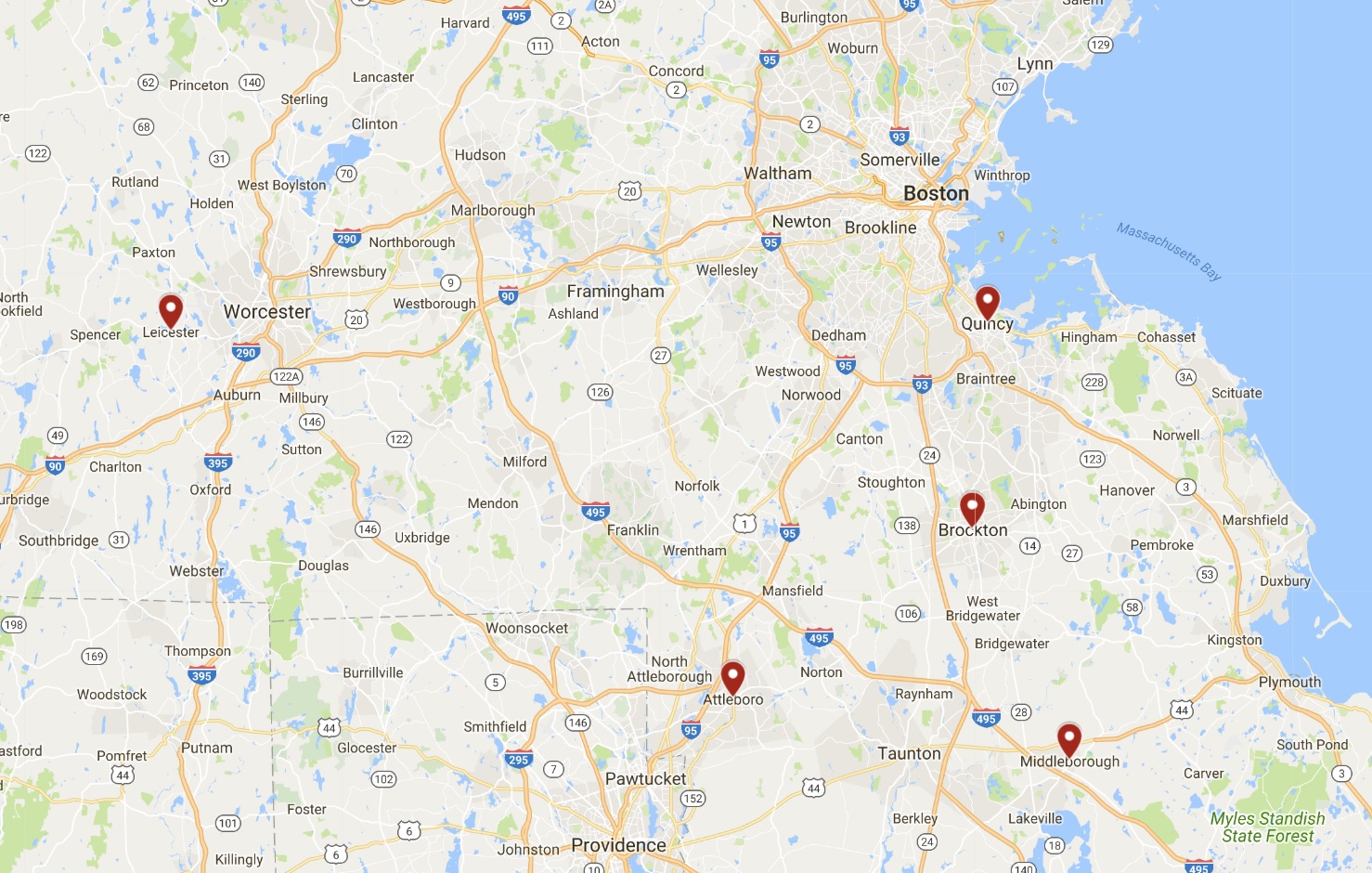

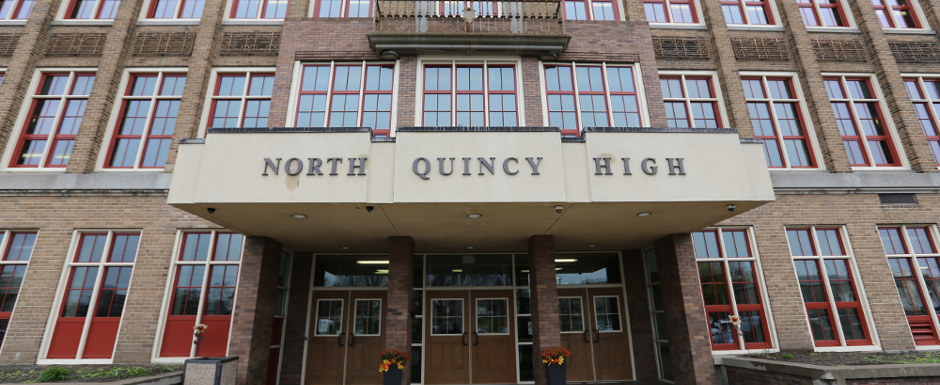

QUINCY

Image via Quincy Public Schools

Just like its northern neighbor Boston, the City of Quincy proudly showcases its affiliation to former U.S. presidents and patriots. With hiking trails, beaches, yacht clubs and historic estates, Quincy offers a unique experience of quiet streets and residential neighborhoods while being minutes away from Boston. In recent years, Quincy has seen considerable commercial growth, making it the ninth largest city in Massachusetts. The merging of old and new influences in Quincy is evident from its residences, restaurants, and schools.

Some school buildings in Quincy are as old as 1919, while some are much more recent. The age of buildings played a role when Quincy’s public school water was tested for lead. Through the DEP’s testing, Quincy reported high levels of lead in more than half of its 20 public schools.

Some alarmingly high results were found, including the 42,000 ppb result in North Quincy High school.

“In many of the cases, the bubblers had failed. Many times bubblers were not maintained and fixtures were broken,” Paul Hines explained. “So if these were bubblers that just dribbled and nobody drank out of them, who knows how long that water was in the valve before it was tested.”

Every fixture in Quincy’s public schools that tested above action level was immediately shut down and has been or will be replaced. Hines and his team are currently putting in new water fountains at Broad Meadows Middle School.

According to Hines, the City Council approved a budget of $275,000 for independent retesting of every fixture in every school. Part of the budget went towards bottled water dispensers in the schools until the faulty fixtures are replaced. However, the city doesn’t want to stop when all fixtures test below the action level.

“We don’t just want to hit today’s standard; we’re trying to improve upon it,” said Paul Hines. “So our goal is to get to 0.005 [mg/l, or 5 ppb], one third of the current acceptable level.”

Suzanne Condon has been closely associated with the issue of lead in drinking water for more than 30 years. She worked on environmental and local health as Associate Commissioner at Massachusetts Department of Health, wrote research papers about children’s health and lead poisoning, and consulted for the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on the Flint, Michigan lead in water crisis. Condon is now working with Quincy Mayor Thomas Koch’s administration as an environmental and public health expert, a job which entails her involvement in the lead testing and remediation efforts.

“We went beyond what anyone asked us to do,” Condon said. “Not just in terms of the testing but also in terms of what we’re doing with those fixtures in the school.”

After testing, Hines and his team formulated a plan to mitigate high lead levels, working with Condon and the school superintendent.

“The early childhood center and the elementary schools were our first priority in doing this.”

Hines explained that they started remedial work in schools attended by the youngest children, since they are most drastically affected by lead.

Communication was also a key aspect of Quincy’s remedial actions. “As we were getting information, we were making sure it was getting out, to all of the people who would be concerned about it,” Condon said. In a meeting held for parents, Condon presented Quincy’s lead testing results and addressed concerns that parents and community members had.

“Quincy has taken this as seriously as one could take it and not just provided open communication, but really clear action in terms of trying to reduce this health risk for children,” she said.

Conclusion

The in-depth look at the five communities revealed that two years after the initial testing through the DEP, most of these cities and towns are continuing efforts to rectify the high levels of lead found in some of their schools.

These are just five out of dozens of towns and cities that availed the free resources offered by the DEP, but there are more than 100 towns in Massachusetts that chose not to. Some of these towns, like Boston, have done independent tests in their public schools. Others have not revealed any public information related to the issue.

“The reason to test in schools is because it isn’t required, and there could be problems that if you don’t test you would never know about it and therefore you can’t take action to reduce the risk of harm to a child.” said Suzanne Condon.

As for these five communities, most of them aimed to solve the problem with whatever resources were available to them.

“It’s about health, it’s about doing it right,” Paul Hines said as he walked out of Quincy’s Broad Meadows school to the faint tune of the school band “As the saying goes, no lead is good lead.”

Image by Paul Goyette via Flickr and is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0