The definitions of most crimes are pretty straightforward. Something is either legal or it isn’t. Domestic violence, however, was long treated as a personal matter rather than a crime - as if beating one’s partner is on the same level as arguing whose turn it was to do the dishes.

A request for domestic violence response policies for state police departments in all 50 states found 28 states willing to release the policies free of charge, or for a small fee. Twelve states reported having no such policy. Four - Hawaii, Kansas, New Hampshire, South Dakota - rejected the request, arguing that granting it would compromise security, reveal confidential law enforcement techniques, or disrupt the operation of government.

The most recent study by the Bureau of Justice Statistics found that between 2006 and 2015, 600,000 cases of domestic abuse went unreported. Thirty-two percent of victims who didn’t report stated it was because the violence was a personal matter, which again, is how the criminal justice system viewed it until relatively recently.

Although the Violence Against Women Act of 1994 established a federal law against domestic violence, the way in which incidents are addressed varies from state to state.

According to the National Center on Domestic and Sexual Violence (NCDSV), in the ’70s and ’80s, only seven to 15 percent of domestic violence incidents resulted in arrest. A 1996 report by the U.S. Justice Department National Institute of Justice (the research and development arm of the DOJ) entitled “The Criminalization of Domestic Violence: Promises and Limits,” offers a bleak history of just how little recourse women had simply because they were married to the person assaulting them.

According to the DOJ report, up until the late 1970s, victims (most of whom were women) couldn’t obtain restraining orders against their abusers without also filing for divorce. That’s a big decision for a traumatized person to make, especially when they’re financially dependant on their abuser. Many police departments discouraged arrest, and when charges were pursued they were dismissed more often than other violent crimes, and in the event a sentence was meted out, it was likely to be lighter than those for non-domestic violent crimes.

About 100 years earlier, Alabama became a pioneer in domestic violence law when in 1871 it became the first state to outlaw beating one’s wife. Fugham v. The State of Alabama ruled that “a married woman is as much under the protection of the law as any other member of the community.” Prior to this ruling men were permitted to employ “moderate correction” in order to ensure that their wives were obedient. As long as they didn’t permanently injure their wives, men could knock them around and remain on the right side of the law. More recently, Alabama has yet to acknowledge our request.

When officers respond to domestic violence incidents there are three basic ways they are required to handle the situation depending on state law. Police operate under systems of mandatory arrest, preferred arrest, and discretionary arrest. Some states have policies that combine these methods. In many states, whether or not an arrest is made in a domestic violence incident is left up to the discretion of police officers.

New Jersey uses a Domestic Violence Response Team (DVRT), comprised of volunteers who advocate on behalf of the victims, and provide information about available services, but in instances in which the victim is deemed “seriously” intoxicated or mentally ill, the police are instructed not to activate the DVRT.

“Seriously impaired” and “impaired” are subjective terms, and the automatic designation of an intoxicated or mentally ill person as “a danger” is arbitrary and ripe for misuse that could result in further trauma for the victim who is left with nobody to advocate and provide information for them. Furthermore, there isn’t a distinction made between seriously mentally ill, and seriously traumatized by having been abused. Police are not mental health professionals and should not be in a position to make that distinction.

New Jersey has a separate policy for state police officers accused of domestic violence, and while having such a policy seems like a positive step, the provision regarding weapon seizure is not applied equally to police and civilians. An officer can “request an expedited court hearing to determine their status regarding the possession of weapons.”

Unlike civilians accused of domestic violence, state police officers can get permission to take back their service weapon as long as they only carry it while on duty, and promise not to enter the victim’s home.

This policy places officers above the law, and puts victims in danger.

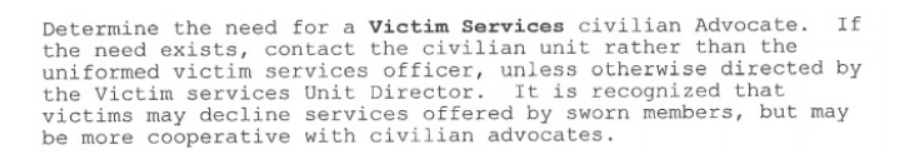

In Delaware, state police policy recognizes that police officers may not be the ideal people for victims to speak with after being attacked, and requires police to determine whether or not the services of a civilian advocate are needed.

Delaware’s policy also specifies that civilian advocates are to be ensured police protection if they are on the scene of the initial response, which makes it possible for victims to have an advocate by their side as they deal with the physical and emotional trauma they’ve just experienced.

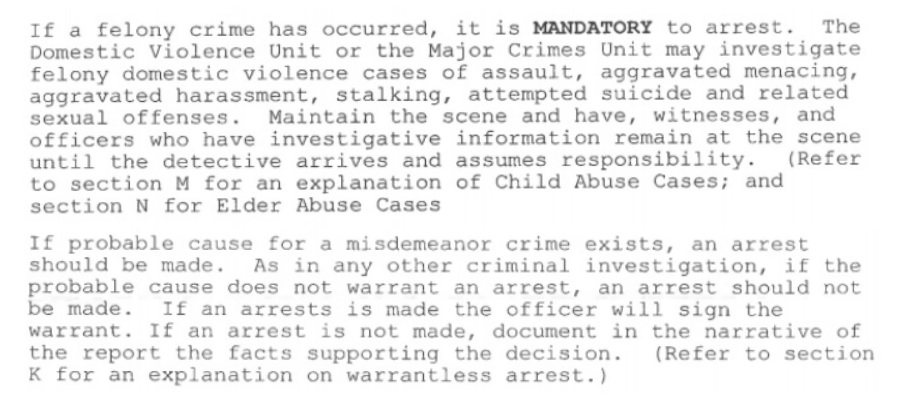

While Delaware policy calls for mandatory arrest in cases in which a felony has occurred, if the incident is a misdemeanor the policy says that the offender “should” be arrested, but stops short of requiring they be arrested.

According to the National Incident Based Reporting System (NIBRS), a federal data gathering system for law enforcement, the most common offense committed in domestic violence incidents is simple assault - a misdemeanor. Simple assault is defined as an attempt to cause serious bodily harm, or making a victim fear that physical violence is inevitable. This means that the law doesn’t demand an abuser be arrested until they actually harm the victim, even if there is evidence that the abuser tried and failed to hurt the victim previously.

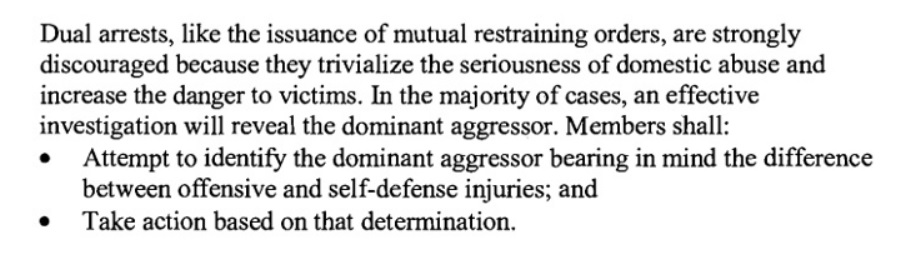

Some states, such as Massachusetts, explicitly discourage dual arrest, which is when both parties make accusations of violence, and both are arrested:

In these states, which also include Hawaii and Ohio, the police are tasked with making their best effort to determine who the primary or “dominant” aggressor was, and arrest them rather than taking both victim and perpetrator into custody.

In mandatory arrest states, the police are obligated to make an arrest if they find probable cause that someone has been assaulted, whether the victim agrees to press charges or not. Mandatory arrest is widely considered to be the safest policy for victims.

Hawaii was one of four states that rejected the request for its domestic violence response policies. Hawaii rejected the request pursuant to a statute that protects “Government records that, by their nature, must be confidential in order for the government to avoid the frustration of a legitimate government function.”

When given a choice, many victims choose not to pursue charges for a number of reasons such as fear of retaliation, being financially dependent on their abuser, or having become so used to the abuse that they consider it a personal matter that the police have no business getting involved in. There’s no one reason - it’s often a grim mosaic of psychological damage, fear, love, and dependency.

Browse the policies through the map embedded below.

Image by Rusty Frank via Wikimedia Commons