The Voyager mission began in 1977 with the launches of Voyager 1 and Voyager 2. The probes flew by our Solar System’s gas giants, taking pictures and sending back measurements. They’re still sending back data today, 39 years later and 12.47 billion miles from Earth.

When I started this project, I hadn’t even considered that the oldest active computer might not even be on Earth. But after my first post, I received a few tips encouraging me to look at the computers onboard Voyager.

Benjamin Levy pointed out how, “the actual computers on board are probably older than [1977] because it takes time to design and build space probes and to certify their computers for their mission,” and another tipster sent me a link to a story about the Voyager team needing to hire a new programmer with experience in FORTRAN.

I’ll admit I was reluctant to pursue these computers at first, but I soon realized that it was silly to disqualify a government computer from this hunt simply because it’s billions of miles away. While the hardware hasn’t been upgraded since it left Earth, the software has been upgraded and maintained to meet new mission requirements. We’re still in touch with these probes and they’re still performing science at the edge of our solar system. Most important, these are government computers and they are both old and active.

A Wired article from September 2013 discusses the computers onboard the Voyager at a high level:

The computers aboard the Voyager probes each have 69.63 kilobytes of memory, total. That’s about enough to store one average internet jpeg file. The probes’ scientific data is encoded on old-fashioned digital 8-track tape machines rather than whatever solid state drive your high-end laptop is currently using. Once it’s been transmitted to Earth, the spacecraft have to write over old data in order to have enough room for new observations.

The article also resolves a question I began my research: does NASA need to keep old terrestrial computers to receive data from the probes?

“Here on the ground, we keep up with the latest technology,” said engineer Suzanne Dodd, the Voyager project manager at JPL [NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory], with most of the science team using Mac power books these days. She recalled when she started working with the mission in 1984, they were using then-state-of-the-art desktop computers with 8-inch floppy drives.

Originally, the Voyager program had planned to custom develop all of their own computers. However, the 70’s brought about an end to NASA’s “blank check” budgeting and cost saving measures began to be introduced. One of the cost reductions on Voyager involved using a Computer Command System (CCS) originally developed for the Viking program. The CCS is primarily responsible for coordinating the other two onboard computers, the Flight Data System (FDS) and Attitude and Articulation Control System (AACS); acting on instructions from Earth; and watching for problems or malfunctions.

The FDS is responsible for recording scientific data from the probe’s instruments and transmitting that data. It was designed in-house at NASA because of its high I/O requirements — it has to broadcast its data at a very high frequency to ensure that it can get all the way to Earth without any loss.

I’ll admit, it feels strange to be writing about such an old machine in the present tense. I’m conditioned by the expectations of consumer computers, of hardware that turns stale gets slower and less reliable with use. Which isn’t to say that the Voyager probes haven’t decayed, but they’ve done so at an order of magnitude slower than the computer on my desk or in my pocket. At the same time, I’ve obtained my computers at a cost that’s a few orders of magnitude cheaper than the cost to build just one of these proves.

But my perspective is also sharply skewed. In my small habitat, computers are a ubiquitous commodity. We’re starting put computers places that never required them, like our lightbulbs and toothbrushes. Out there, on the edge of the Solar System and at the frontier of human exploration, we only have a couple of computers. Once they’re done working, that’s it. That’s as far as we can go, until we send another probe.

I’m glad these machines can run almost 40 years without fail. It’s a refreshing change of perspective to know that the computers I’ve been trained to see as delicate, fragile, and disposable systems are capable of such high level of endurance.

Or as Gizmodo’s Maddie Stone put it during last week’s presidential debate:

The only winner tonight is the Voyager probe, which is speeding away from the Earth at 17 kilometers/second #debatenight— Maddie Stone (@themadstone) September 27, 2016

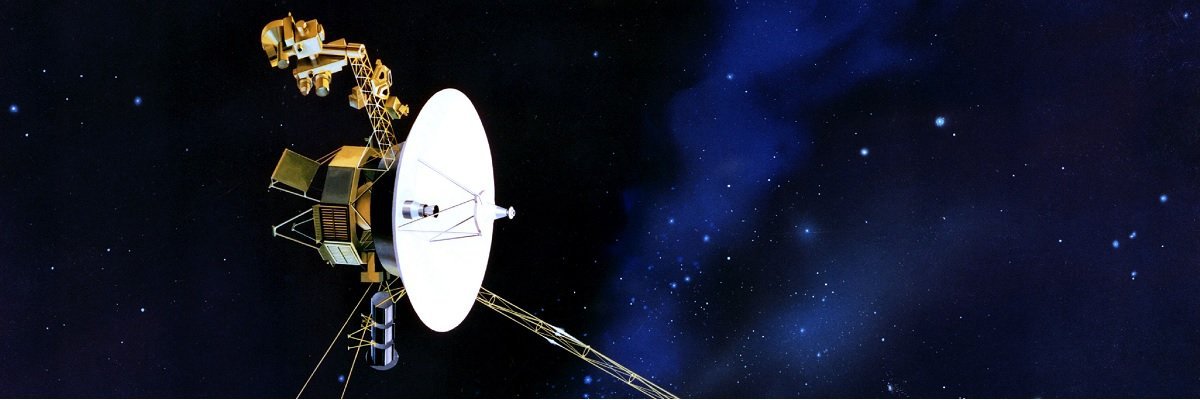

Image via Wikimedia Commons