Documents obtained from Boston City Hall through a public records request reveal that approximately 37 percent of precincts in the Boston metro area reported technological issues or system malfunctions with their voting machines in the 2012 general presidential election.

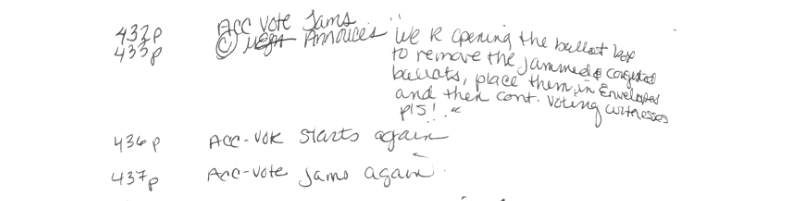

According to poll workers’ reports from the 2012 election, at least 96 of the 255 precincts reported issues ranging from “lights out in voting booth” to “ballot count screwed up” and “machine shut off completely.” The most common complaint that poll workers had with the voting systems was “scanner jammed.”

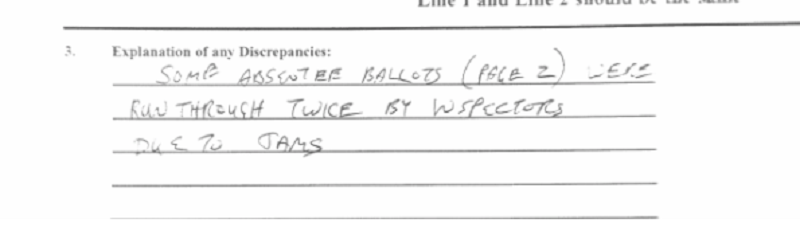

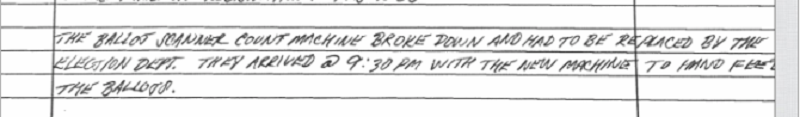

To fix the jam, the poll workers have to call in a repairman to physically open the machine up, remove the offending ballots, and reset the system. Often, the poll workers reported consecutive jams.

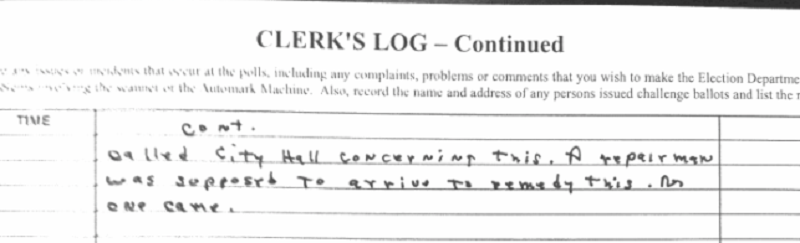

In one instance, a repairman simply never showed up.

So how did this happen?

Massachusetts currently uses optical scanning equipment which takes in hand-marked paper ballots and tallies up the results at the polling location. Boston uses one of two different brands of voting equipment: the ES&S AutoMark and the Premier/Diebold (Dominion) AccuVote.

The problem is, the laws around certifying and regulating these machines are hazy.

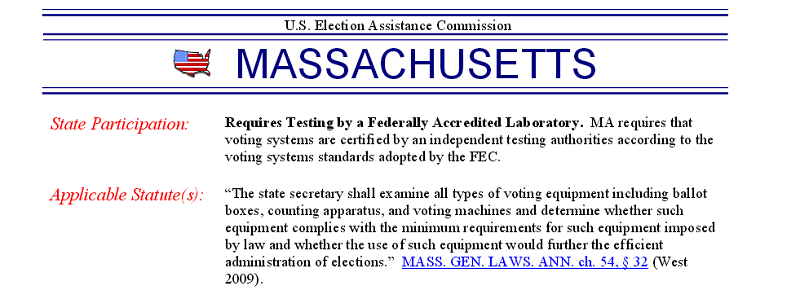

The U.S. Election Assistance Commission (EAC) was created in 2002 as a part of the federal Help America Vote Act (HAVA) and was tasked with establishing some form of standardization for voting machines nationwide. What it came up with was the Voluntary Voting System Guidelines (VVSG) which outlines the standards and regulations that all voting machines should adhere to. The catch, of course, is that these guidelines are “voluntary.”

Typically, jurisdictions will purchase their own voting systems which have been submitted for testing by the individual vendors. The vendors are responsible for assuring that the machines meet required standards (state standards at least, sometimes federal standards). After these machines are tested and approved for use, states can purchase them. However, the requirements vary from state to state.

As it stands, 37 states, including Massachusetts, require some aspect of federal testing. However, nine states have no federal testing or certification requirements whatsoever. With regard to these nine states (Florida, Maine, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Oklahoma, Oregon and Vermont), the National Conference of State Legislature website says:

“Statutes and/or regulations make no mention of any federal agency, certification program, laboratory, or standard; instead these states have state-specific processes to test and approve equipment (Note that even states that do not require federal certification typically still rely on the federal program to some extent, and use voting systems created by vendors that have been federally certified).”

The remaining four states refer to the federal standards but fall under other categories of certification.

But, as evidenced by the issues poll workers experienced in the 2012 election, even federal testing cannot prevent all malfunctions. At one precinct, the safety seal on the ballot box fell off.

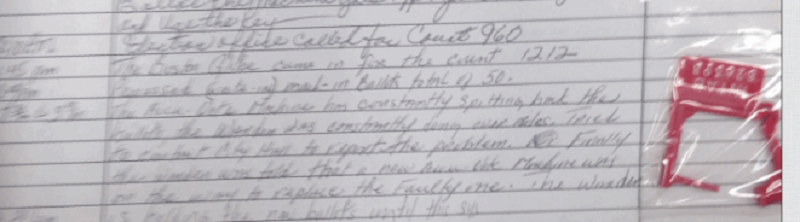

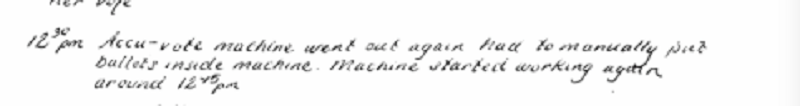

Poll workers had to “manually put ballots inside machine.”

These issues went as far as to cause discrepancies in the precinct’s totals.

And in one case, an entirely new machine had to be brought in.

The source of these glitches and malfunctions wasn’t cited in the reports, however, most of the issues can be attributed to aging equipment. Funding from HAVA for the voting machines was distributed to jurisdictions in a lump sum disbursement rather than in stipends over time. So, while the machines purchased with HAVA funding were all initially shiny and new, any repairs to the equipment would come at a cost to the state.

According to a study put out by the Brennan Center for Justice at the New York University School of Law, in 2016, Massachusetts will be using voting equipment that was purchased more than 15 years ago. And with each machine running a cost of around $3,000 multiplied by two units per precinct, the cost for Boston alone would near $1.5 million to replace them all.

The poll workers’ reports, which can be accessed at the election department at Boston City Hall, are all handwritten and are not digitized. When asked what happens with these reports after the election concludes, Sabino Piemonte, acting elections chief for the city of Boston, said that a committee reads through them and issues a processing report citing any changes that may need to be made. That processing report was unavailable as of this article’s publication.

A sample of the logs can be read on the request page, or embedded below:

Image via Wikimedia Commons