For kids like Sandy Mitchell, Ted Theis and Janet Johnson, childhood in the North St. Louis County suburbs in the 1960s and ‘70s meant days playing along the banks or splashing in the knee-deep waters of Coldwater Creek.

They caught turtles and tadpoles, jumped into deep stretches of the creek from rope swings and ate mulberries that grew on the banks.

Their families — along with tens of thousands of others — flocked to the burgeoning suburbs and new ranch style homes built in Florissant, Hazelwood and other communities shortly after World War II. When the creek flooded, as it often did, so did their basements. They went to nearby Jana Elementary School and hiked and biked throughout Fort Belle Fontaine Park.

![An undated photo from the 1980s, of a child swinging from a rope into Coldwater Creek. The photo is from a scrapbook kept by Sandy Delcoure, who lived on Willow Creek in Florissant and donated the scrapbook to the Kay Drey Mallinckrodt Collection. Only one of the photographs from the scrapbook includes any information, which read: “Willow Creek children on Cold Water [sic] Creek. We can’t keep the children away from the creek. The only alternative is to get it cleaned up.” (State Historical Society of Missouri, Kay Drey Mallinckrodt Collection, 1943-2006.)](https://cdn.muckrock.com/news_photos/2023/07/11/Archive-01.jpg)

Growing up, they never knew they were surrounded by massive piles of nuclear waste left over from the war.

Generations of children who grew up alongside Coldwater Creek have, in recent decades, faced rare cancers, autoimmune disorders and other mysterious illnesses they have come to believe were the result of exposure to its waters and sediment.

“People in our neighborhood are dropping like flies,” Mitchell said.

The earliest known public reference to Coldwater Creek’s pollution came in 1981, when the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency listed it as one of the most polluted waterways in the U.S.

By 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was advising residents to avoid Coldwater Creek entirely. Cleanup of the creek is expected to take until 2038. A federal study found elevated rates of breast, colon, prostate, kidney and bladder cancers as well as leukemia in the area. Childhood brain and nervous system cancer rates are also higher.

“Young families moved into the area,” Johnson said, “and they were never aware of the situation.”

Theis, who grew up just 75 yards from the creek and played in it daily, died in August at the age of 60 from a rare cancer. Mitchell is a breast cancer survivor whose father died from prostate cancer. Johnson’s sister has an inoperable form of glioblastoma and other family members, including her father, daughter and nephew, have had various cancers.

Families who lived near Coldwater Creek were never warned of the radioactive waste. Details about the classified nuclear program in St. Louis were largely kept secret from the public. But a trove of newly-discovered documents reviewed by an ongoing collaboration of news organizations show private companies and the federal government knew radiological contamination was making its way into the creek for years before those findings were made public.

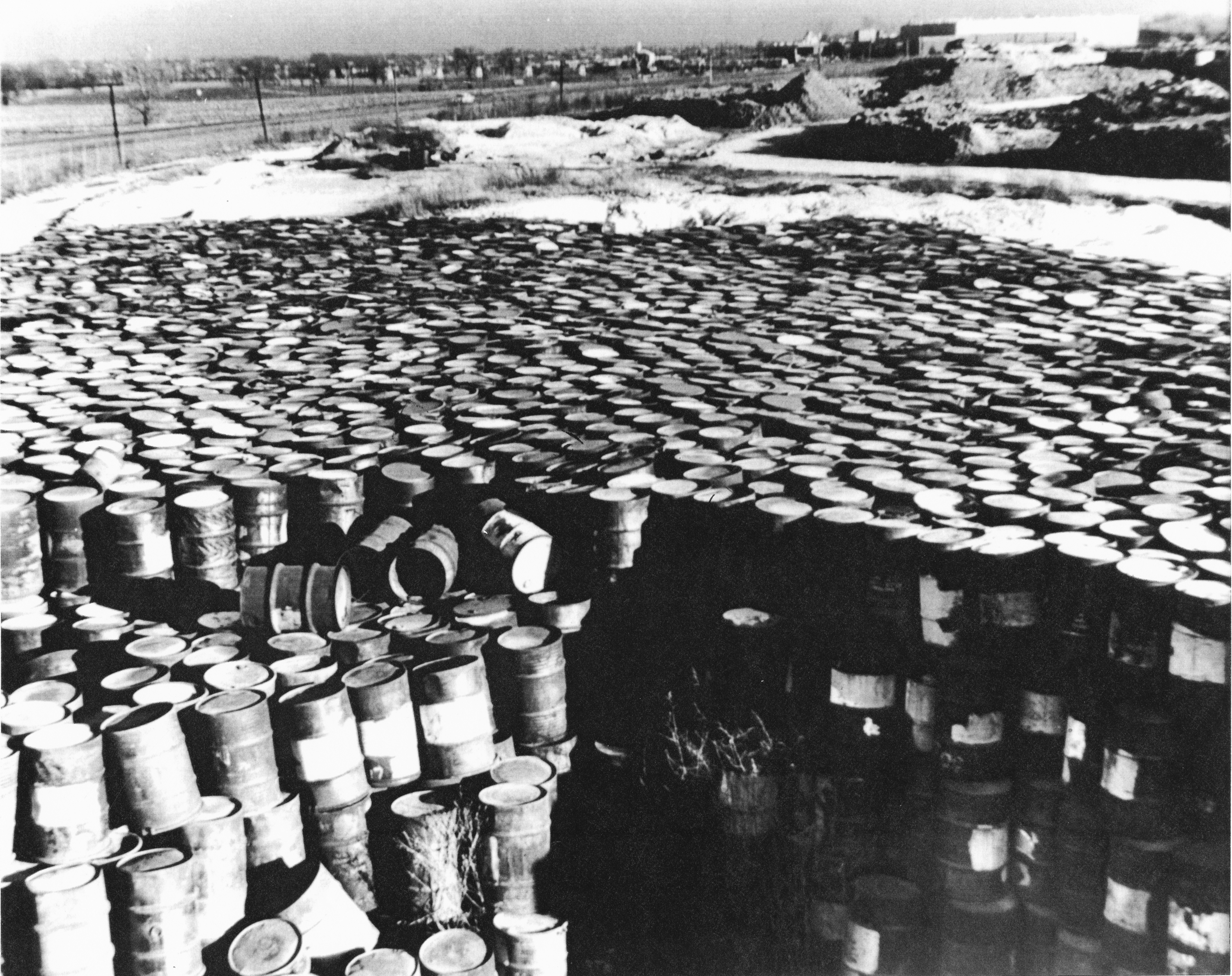

Radioactive waste was known to pose a threat to Coldwater Creek as early as 1949, records show. K-65, a residue from the processing of uranium ore, was stored in deteriorating steel drums or left out in the open near the creek at multiple spots, according to government and company reports.

A health expert who, as part of this project, was recently presented with data from a 1976 test of runoff to the creek concluded it showed dangerous levels of radiation 45 years ago.

Federal agencies knew of the potential human health risks of the creek contamination, the documents show, but repeatedly wrote them off as “slight,” “minimal” or “low-level.” One engineering consultant’s report from the 1970s incorrectly claimed that human contact with the creek was “rare.”

The Missouri Independent, MuckRock and The Associated Press spent months combing through thousands of pages of government records obtained through the Freedom of Information Act and interviewing dozens of people who lived near the contaminated sites, health and radiation experts and officials from government agencies.

Some of the documents, obtained by a nuclear researcher who focuses on the effects of radiation, had been newly declassified in the early 2000s. Others had been previously lost to history, packed away in government archives and not released publicly until now. (Read the documents here and learn more about our methodology here.

All told, the documents from the now-defunct Atomic Energy Commission; its successors, the U.S. Department of Energy and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission; and the Environmental Protection Agency span the 75-year lifespan of the nuclear saga in St. Louis.

It starts in downtown St. Louis, where uranium was processed, and at the St. Louis airport, where it was stored at the end of the war; a monthslong move of the waste to industrial sites on Latty Avenue in suburban Hazelwood and a quarry in Weldon Spring, next to the Missouri River; an illegal dumping of waste at the West Lake Landfill in Bridgeton in the 1970s by a private company; and the declaration of the landfill as a federal toxic Superfund site in 1990.

Since then, the contaminated sites have been subjected to a seemingly endless cycle of soil, air and water testing, anxious community meetings attended by an ever-growing chorus of angry residents and panic when a subsurface smoldering event, similar to an underground fire, at the Bridgeton landfill threatened the radioactive waste buried nearby. That fire sent noxious and hazardous fumes into surrounding neighborhoods. The company in charge of the Bridgeton landfill now spends millions a year to contain it.

The documents have a familiar cadence: Year after year, decade after decade, government regulators and companies tasked with cleaning up the sites downplayed the risks posed by nuclear waste left near homes, parks and an elementary school. They often chose not to fully investigate the potential harms to public health and the environment around St. Louis.

Bob Criss, a now-retired geologist and geochemist, studied St. Louis’ history with nuclear waste at Washington University in St. Louis and wrote a report in 2013 critical of the EPA’s stewardship of the West Lake Landfill Superfund site.

In an interview last month, Criss said the waste changed hands so often and was overseen by an assortment of lightly regulated private companies, resulting in what he called a “ridiculous chain of events…driven by irresponsibility.”

“The government should have been responsible for this material,” Criss said.

The Department of Energy has assisted with the costs of remedial studies at West Lake under a legal agreement called a consent decree since 1993. It referred questions about the landfill’s history and other contaminated sites to the Department of Justice, which did not respond to a request for comment, and the Environmental Protection Agency.

Presented with details of the newly-revealed documents, Dave McIntyre, a spokesperson for the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, said in a statement that the agency conducted numerous investigations and studies at the West Lake Landfill over a period of almost 20 years that were “extensively documented.” It transferred authority to the EPA in 1995 and directed further questions to the agency.

The EPA has jurisdiction only over the West Lake site. Staffers for the agency acknowledged cleanup at the site had been slow, but there has been progress toward designing an excavation plan and placing a cap on the landfill.

St. Louis becomes vital piece of Manhattan Project war effort

The St. Louis region proved pivotal to the development of the first atomic bomb in the 1940s.

Old downtown factories, suburban storage sites and the landfill represent some of dozens of properties that were contaminated in pursuit of the nuclear bomb.

The West Lake Landfill is one of well over 1,000 EPA Superfund sites across the country. The Department of Energy, too, is the steward of other nuclear sites, like a complex in Hanford, Washington, on the banks of the Columbia River, in desperate need of cleanup.

Mallinckrodt Chemical Works processed uranium for the Manhattan Project, the name given to the effort to build the bomb, in downtown St. Louis. Uranium from the Mallinckrodt plant was used in the first sustained nuclear reaction in Chicago, a significant breakthrough.

By the end of the 1940s, there was already a risk of contamination, the new records show.

An internal Mallinckrodt memo from 1949 shows the company was storing highly radioactive residue called K-65 in deteriorating steel drums at the St. Louis airport near Coldwater Creek. The material was so dangerous, the memo said, that Mallinckrodt couldn’t simply put it in new containers because “the hazards to the workers involved in such an occupation would be considerable.”

Mallinckrodt, which still exists as Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, declined to comment for this article. By 1960, the company had more than 1,000 employees at its uranium processing facility in St. Louis. It took some measures to protect its workers, such as putting them on timed shifts to limit exposure, but it determined possible pollution of Coldwater Creek was far less “serious and immediate” than the threat handling the waste posed to workers.

As the nation’s oldest radioactive waste of the atomic age, many details about Mallinckrodt and other private companies’ storage and maintenance of nuclear waste have been well documented, first as part of a grassroots civic effort in the 1970s by environmental activist Kay Drey and then as part of a seven-part series published by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in 1989.

More recently, the issue was the focus of a 2017 documentary called “Atomic Homefront” and a 2022 book, “Nuked,” by Linda Morice, who grew up near Coldwater Creek.

But the new documents reveal government agencies were plainly aware of the risks posed by prolonged storage and seepage of waste into soil, groundwater and the creek — and yet dismissed concerns about them.

Following the war, material from Mallinckrodt was trucked to a site next to the airport, which would later become the center of some of the region’s most populated suburbs. At times, waste fell out of trucks and spilled onto public roadways, only to be picked up by a single worker carrying a shovel and broom and loaded back onto the bed of a pickup truck. It was then left for years in the open, without a cover, where wind and rainwater dispersed it.

After a few years, the Atomic Energy Commission, which was later replaced by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, began looking for a buyer for the waste. A private company would purchase the waste, process it to obtain any valuable materials — such as copper, nickel or cobalt — and dispose of the rest.

While the waste awaited purchase, a 1965 government report found drainage from the 20-foot-tall mounds of material — including almost 200 tons of uranium — had produced “some minor contamination in Coldwater Creek.”

The document doesn’t specify the level of radiation in the creek at the time, but it says the levels are “well within permissible and acceptable limits.”

Within a few years, most of the waste was sold and moved just up the road to a site on Latty Avenue in Hazelwood where it, again, sat exposed to the elements and adjacent to Coldwater Creek.

But despite the move, the airport would remain contaminated for years to come.

Between 50 and 60 truck loads remained buried there, and in the late 1970s, uranium, radium and thorium were found in the drainage ditches along a public road next to the site.

According to a draft report uncovered as part of the document release, four members of the health and safety research division of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee tested the airport site in 1976 at the request of the Energy Research and Development Administration, which would become the Department of Energy.

The results showed onsite radiation sources were as high as 8.8 millisievert per year, five times the typical dose of radiation humans receive in a year, and nine times the EPA’s limit for water pathways, according to an expert who calculated the annual dose for the Independent and MuckRock. The reading was 220 times higher than the EPA’s limit for drinking water pathways.

Though the federal government knew about the contamination, the public wouldn’t find out until 1990.

“These site doses are deadly because there is no safe dose of radiation,” said Kristin Shrader-Frechette, professor and PhD with the University of Notre Dame’s Biological Sciences Department and Environmental Sciences Program, who reviewed the 1976 study’s findings.

The runoff sources next to Coldwater Creek, Shrader-Frechette said, are “far higher than what is allowed. The only question is whether any scientific studies have documented these health problems.”

In 1979, the Department of Energy acknowledged the site was eroding, carrying contamination into the drainage ditch and Coldwater Creek. But a planned meeting that November, with representatives of multiple federal agencies and local elected officials, was abruptly canceled after then-U.S. Rep. Robert Young openly fought with the federal agencies over a lack of funding for the cleanup.

In a description of a meeting between Young and a Nuclear Regulatory Commission official, the congressman railed against the federal government, saying St. Louis and its airport had been “hoodwinked” into taking ownership of the radioactive waste, which he described as a “Pandora’s Box.”

The airport site wasn’t fully cleaned up until 2009.

In 1986, then-St. Louis City Health Commissioner William B. Hope Jr. wrote to a city alderwoman that he had been “quietly” testing Coldwater Creek and city water supplies, to ensure the city’s drinking water wasn’t contaminated. It wasn’t, he found, but he offered a blunt assessment of the federal government’s nuclear waste program in the St. Louis region.

“Sufficient information was known about the radioactive contaminants to have warranted a different type of decision regarding their disposal,” he wrote. “These materials should not have been deposited near populated areas and certainly not in areas where geographically the material could migrate into the water table or into adjacent areas as a result of erosion over time.”

Illegal dumping of radioactive waste

When the Atomic Energy Commission sold the remnant nuclear waste, it anticipated being able to get rid of the more than 100,000 tons of toxic residues without spending any money.

The first company to purchase the waste, Continental Mining and Milling Co. of Chicago, borrowed $2.5 million to buy it in 1966 and then, shortly after, went bankrupt. Continental’s lender, Commercial Discount of Chicago, re-purchased the waste at auction for $800,000 and, after failing to get a bidder at a second auction, sold it to the Cotter Corp. To turn a profit, Cotter would ultimately dry the material and ship it to its uranium mill plant in Cañon City, Colorado.

By 1972, most of the valuable metals in the waste had been identified and shipped. Cotter was now looking to dispose of remaining waste that had little or no monetary value — 8,900 tons of worthless leached barium sulfate and “miscellaneous residues and debris.”

But the cost estimates to properly dispose of the waste were pricey: $150,000 ($1.1 million in 2023 dollars) to bury it onsite at Latty Avenue near Coldwater Creek or about $2 million ($15 million in 2023 dollars) to ship it hundreds of miles away to a commercial site in West Valley, New York, and bury it there.

A third location was proposed: A pit at the Weldon Spring quarry in St. Charles County, which was already a disposal site for other radioactive waste.

The Atomic Energy Commission had initially planned to allow it to be dumped in the Weldon Spring quarry, just outside the banks of the Missouri River, when it was looking for a buyer for the waste in 1960, government records show.

But on the advice of the U.S. Geological Survey, the Atomic Energy Commission reversed course on the quarry plan. Among other issues, the agencies said there was a “high probability of contaminating the Missouri River shortly above the intakes for the St. Louis City and St. Louis County water supplies.”

Cotter asked the government to bury the waste at Weldon Springs multiple times, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, but were rebuffed each time, meeting minutes show.

So, over a period of 2 ½ months in the summer and fall of 1973, Cotter took the problem into its own hands, without telling government regulators.

The company mixed the radioactive waste with tens of thousands of tons of contaminated soil from the site and illegally dumped it in a free, public landfill called West Lake, under three feet of soil and other garbage.

Within months, the Atomic Energy Commission discovered what Cotter had done.

Government records show staffers from the commission visited the site as part of a routine inspection in April 1974 and were told about the illegal dumping. Internal memos and letters show AEC staffers believed Cotter’s actions violated agency regulations and were misled about the amount of the waste involved.

Internally, the AEC struggled with how to respond to Cotter’s illegal dumping.

While noting Cotter was “clearly in violation” of a federal law “in that [the company] disposed of licensed material in an unauthorized manner,” “the large numbers involved need to be brought into prospective (sic).”

Cotter had mixed enough topsoil with the radioactive waste to, in theory, render it harmless, the agency concluded.

AEC’s enforcement division found that the waste in the West Lake Landfill was now “virtually unidentifiable and nonrecoverable.” Still, Cotter should provide evidence that the waste “does not constitute an undue hazard to the public or the environment.”

A draft letter by the AEC to Cotter was drawn up, requiring the company to study the potential environmental and health consequences of dumping the waste at the West Lake Landfill and propose solutions.

But that requirement was cut from the final letter, without explanation. The decision to let Cotter off the hook was not revealed to the public.

Cotter subsequently informed the AEC that it had finished processing the waste and decontaminating the property and asked the government to terminate its license and release it from responsibility over the site.

The AEC released Cotter from its St. Louis permit without immediate sanctions in 1974, but the company is partially responsible for the cleanup costs at the site.

Cotter’s parent company, General Atomics, did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

By most government accounts, the human health risk at the West Lake Landfill is remote. Lee Sobotka, a chemistry and physics professor at Washington University in St. Louis, has studied the radiation levels at West Lake Landfill site and noted that the waste is diluted enough to be considered “low-level.”

Despite the low risk of illness, Sobotka said the government, and by extension the surrounding communities, are left with a never-ending cleanup and maintenance problem. Federal and state agencies will have to be a “custodian in perpetuity” at West Lake.

“Looking back at history, you find a litany of mistakes by companies and contractors and so you can get very upset about that,” he said.

Looking forward, Sobotka said, “it’s not something you seal and forget.”

‘Tip of the iceberg’

In 1999, when Robbin Dailey moved into Spanish Village, a neighborhood of only a few dozen homes with its own park less than a mile from the back side of West Lake Landfill, she had no idea she was living next to a Superfund site.

When the EPA decided initially in 2008 to cap the waste at West Lake and leave it in place, Dailey never heard about the plan. Two years later, in 2010, she was alerted to the radioactive waste when a “subsurface smoldering event” — a type of chemical reaction that consumes landfilled waste like a fire but lacks oxygen — sent a pungent stench into the air around her home.

Dailey and her husband had their house tested and found thorium in the dust at hundreds of times natural levels. They sued the landfill’s owners, Republic Services, as well as the Cotter Corp. and Mallinckrodt.

Dailey said she and the companies had “resolved” their legal issues, but she, like all of the residents in North St. Louis County, was still in the dark about where within the landfill site the waste actually was.

Court records reveal a bevy of lawsuits against the private companies involved, at various times, with the West Lake Landfill. Not only that, but the landfill operators sued Mallinckrodt in an attempt to force the maker of the radioactive waste to pay for part of the cleanup.

Since the late 1970s, federal regulators repeatedly failed to uncover the true extent of contamination at West Lake.

In October 1977, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission used a helicopter to take hour-long passes back and forth over the landfill from an altitude of 200 feet. The goal was to measure gamma radioactivity coming from the site using specialized equipment.

While the effort correctly identified two areas with high levels of radiation, it had serious limitations, experts say. A survey of that type can miss contamination if it’s buried deep underground or if the ground is obstructed by vegetation.

And it did.

Despite the shortcomings of that sort of test, the government’s conclusion that the radioactive waste was confined to two areas of the West Lake Landfill would stand for more than 40 years.

Nathan Anderson, a director of natural resources and environment for the federal Government Accountability Office, said the federal government often fails to compile complete and reliable information in environmental cleanups.

“We’ve done a number of these evaluations where there is contamination that the federal government is on the hook for cleaning up,” Anderson said. “And we’ve found that oftentimes, it’s the tip of the iceberg.”

In May, almost 50 years after the waste was dumped at West Lake, the Environmental Protection Agency acknowledged what many residents had long feared: Radiological waste was spread throughout the West Lake Landfill, not confined to two specific portions as officials had long maintained.

Bob Jurgens, the EPA’s superfund and emergency management division director for the region, announced at the community meeting in May that the health risk “remains unchanged.”

The additional radioactive waste is largely underground, he said, so “we believe that is protective at this time to the folks that are outside.”

EPA officials said the contamination was found all over the property — in some areas at the surface and, in other areas, at great depths.

The agency looked at the dates on newspapers above and below the radioactive waste in two areas of the site previously thought to be uncontaminated to approximate when it was dumped, said Chris Jump, the EPA’s lead remedial project manager for the site.

It’s likely been there the whole time.

In one area where contamination was at the surface, the EPA moved quickly to add gravel and rocks to cover it. The waste had migrated outside the fence line in some areas, the EPA said.

Readings showed contamination in a drainage ditch along a public road bordering the landfill. It migrated right under the EPA’s nose.

While the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry did not find any causal link between the West Lake Landfill and illnesses in and around Bridgeton, it said in a 2015 report that radon concentrations appeared higher than typical. It encouraged further testing using long-term monitoring devices.

Dawn Chapman, who left her job and co-founded Just Moms STL to advocate for the community around the landfill, said the EPA used to treat her and other activists like their fears were hysterical.

“We spent more time fighting them as an agency than we did the g—–n polluters,” Chapman said.

EPA officials, in an interview last month, acknowledged the flyover and previous testing missed considerable areas containing radioactive waste. But they said they did not need to test soil over the whole site before deciding on a partial excavation strategy.

“It doesn’t change anything about the remedy itself. It doesn’t change anything about the risks that the site poses,” said Tom Mahler, a remedial project manager for the EPA. However, Mahler said finding all of the contamination was important for the next step of the work at the site: designing and executing the excavation.

State pleads for help

By the time the EPA listed the landfill on the National Priorities List in 1990, state officials had already been sounding the alarm for years.

A staffer with the Missouri Department of Natural Resources wrote in 1980 that contamination at the landfill was more severe and widespread than previously thought. In 1986 and 1990, onsite sampling showed possible radiological contamination in the groundwater in areas outside the sections of the landfill thought to be radioactive.

In 1987, the state classified the landfill as a hazardous waste site. The radioactive waste was in direct contact with the groundwater, the agency said in its annual report.

“Based on available information, a health threat exists due to the toxic effects of chemicals and low-level uranium wastes buried at the site and the possibility that off-site migration of these materials might occur,” the agency wrote.

The next year, Missouri began lobbying the EPA to designate the landfill as a Superfund site, contending that the Nuclear Regulatory Commission knew the site needed to be cleaned up but had no intention of taking action and the Department of Energy said the site didn’t qualify for its cleanup program.

Yet there was little movement from the federal agencies – despite growing evidence.

A 1982 study commissioned by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission showed that, as the waste in the landfill decays, radium activity will increase by nine times over 200 years.

Despite that finding, as of 1984, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission believed stabilizing the waste and leaving it onsite was the best solution, in part, because of the high cost of alternative solutions, such as excavating the site or new construction to control groundwater.

A Nuclear Regulatory Commission report from 1988 shows radioactivity in the groundwater on site anywhere from two to 30 times levels it would occur naturally.

“Based on monitoring-well sample analyses, some low-level contamination of the groundwater is occurring,” the report says, “indicating that the groundwater in the vicinity is not adequately protected by the present disposition of the wastes.”

Even after the Superfund declarations, Missouri and the EPA sparred over how the contamination was quantified.

The Missouri Department of Natural Resources told the EPA in 1997 that it feared the extent of the contamination was underestimated. Until disagreements around how to calculate the severity of the contamination and whether sampling showed false positives were resolved, the agency said, “we cannot concur with the conclusion that the…extent of the contamination has been defined.”

Ryan Seabaugh, project manager for the West Lake site for the Missouri Department of Natural Resources, said in an interview that the state agency asked the EPA to do more testing or provide information to confirm the boundaries of the contamination.

“We just had concerns that there might be a little bit more,” said Seabaugh, who has overseen the site for the state for eight years. “We were pretty surprised at the relatively large extent that we did find.”

It wasn’t until around the time the EPA settled on a plan to excavate parts of the site in 2018, Seabaugh said, that the federal agency started “listening” to its Missouri counterpart.

After several studies, the EPA designated the groundwater at West Lake as its own “operable unit” to be investigated and, potentially, remediated. That work is ongoing.

Still, even by the EPA’s admittedly slow process for classifying and cleaning up toxic sites, the West Lake Landfill timeline was glacial. For Superfund sites listed in 1996, it took an average of more than 9 years from discovering the site to placing it on the National Priorities List. Cleanup took an average of 10 ½ years, a Government Accountability Office review found.

The West Lake Landfill contamination was discovered in 1974. It was designated a Superfund site in 1990, and there is still no date certain for when the cleanup will begin.

John Madras, who worked for the Missouri Department of Natural Resources at the time it was asking the EPA to classify West Lake as a Superfund site, said that, even among slow-moving government cleanup projects, West Lake stands out: “They’ve given us a new understanding of what a really long time is.”

Back to the drawing board

EPA’s first plan for the site would not have included moving the radioactive waste at all.

In 2008, the Environmental Protection Agency approved a plan for the landfill’s “primarily responsible parties” — the government and private contractors responsible for the site — to place a cap over the landfill and leave the waste in place.

Following criticism from the surrounding communities, EPA asked the Department of Energy, the Cotter Corp. and the landfill’s owner, Republic Services, to test the site again.

In the meantime, an underground fire brought a new level of scrutiny.

Starting in 2010, the Bridgeton landfill, which sits adjacent to the West Lake Landfill, has been experiencing a subsurface smoldering event.

The smell from the heated trash got the attention of the Bridgeton community when it worsened in 2013. The situation also caught the attention of then-Missouri Attorney General Chris Koster, who sued the landfill’s owner, Republic Services, for its track record at the Bridgeton landfill.

And as Koster’s office investigated the site, it too became concerned the EPA was underestimating the risk. Testing performed in preparation for a fire barrier to keep the reaction from reaching the radiological contamination, Koster wrote, appeared to demonstrate that the waste was not confined just to where the EPA thought.

Koster’s office would release additional findings as part of its investigation for the lawsuit against Republic Services, including reports in 2015 that radioactive waste had been found in vegetation offsite and the fire was moving closer to the onsite contamination, which the EPA dismissed as “unhelpful” at the time and continues to dispute.

In the midst of strife over the stench and studies conducted in search of a new plan, the owners of the landfill decided to fence off one of the two areas then thought to contain the radioactive waste.

But as it turned out, they were digging in close proximity to radioactive waste.

After construction of the fence began, the Missouri Department of Natural Resources visited the site in June 2013 with a portable radiation reader. State officials found radiation at levels 35 to 50 times what is normal in the tire ruts leaving the site and just a short distance from the post holes dug along the planned fence line.

The department flagged the finding for the EPA, the documents show.

“Elevated readings indicated an area of radiologically contaminated soils located within close proximity to the new fence installation and also in close proximity to the exit route from the landfill,” Shawn Meunks, then the project manager for West Lake for DNR, wrote in an email.

Meunks warned the contaminated soil could be spread by trucks leaving the site. A consultant for the government and private companies wrote back, saying crews realigned the fence so the contamination would be contained within the boundaries. The consultant’s email said testing along the new fence line showed no elevated levels of radiation.

“Therefore no ‘track out’ or erosional transport had occurred,” the email said.

But since then, testing in preparation for the remediation at the site has uncovered radioactive contamination all along that fence.

“Knowing what we know now based on the new EPA findings, I don’t see how they couldn’t have been digging in it,” said Christen Commuso, a spokesperson for the nonprofit advocacy organization, the Missouri Coalition for the Environment.

The EPA has said the additional contamination found along that fenceline is below the surface.

The depth and severity of the new contamination the EPA found is not yet clear. The agency is preparing to release a report that will include the readings, a spokesperson said. A remedial design portion of the project is underway, the last step before the excavation begins.

But EPA doesn’t have a date certain as to when work on the project might start.

Curtis Carey, a spokesperson for the EPA, said despite decades of delays, the agency is planning next steps for the landfill “with a great deal more information because of our purposeful approach than was available 10, 15, 20 years ago.”

The following people contributed reporting, writing, editing, document review, research, interviews, photography, illustrations, analysis and project management. Chris Amico, Dillon Bergin, Kelly Kauffman and Derek Kravitz of MuckRock; Jason Hancock, Allison Kite and Rebecca Rivas of The Missouri Independent; Michael Phillis and Jim Salter of The Associated Press; Sarah Fenske, Theo Welling, Tyler Gross and Evan Sult of the Riverfront Times; EJ Haas, Madelyn Orr, Sydney Poppe, Mark Horvit and Virginia Young of the University of Missouri; Katherine Reed of the Association of Health Care Journalists; Liliana Frankel, Erik Galicia, Laura Gómez, Lauren Hubbard, Sophie Hurwitz and Steve Vockrodt; and Gerry Everding and Carolyn Bower of the original St. Louis Post-Dispatch team that published the seven-part “Legacy of the Bomb” series in 1989.

Illustration by Tyler Gross (Riverfront Times).